Q. How did you become interested in Central Europe? Is your background ‘Central European’?

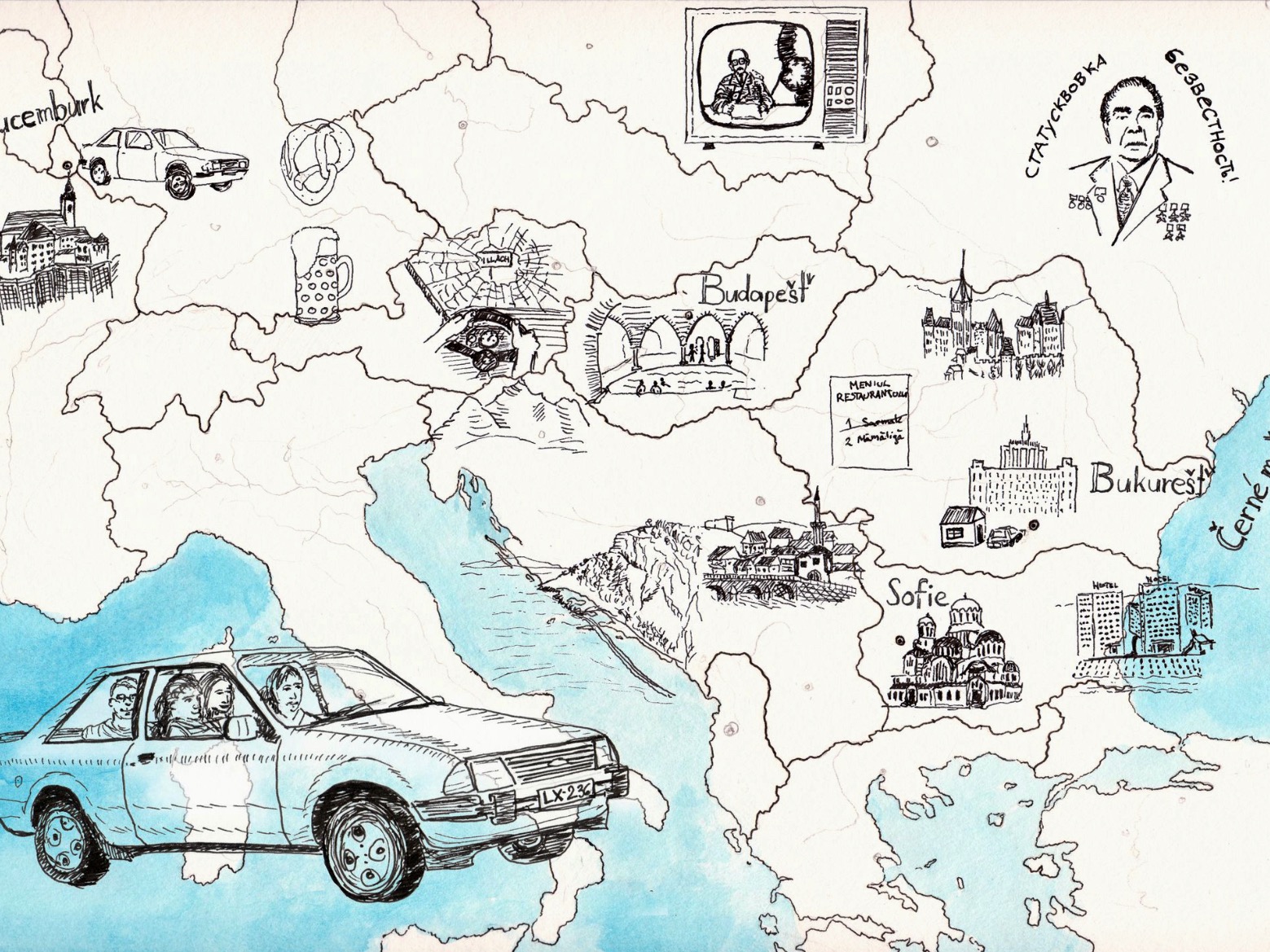

MB: With a name like "Mark Baker," it's hard to justify any family connection to Central Europe. I grew up in a city (Youngstown, Ohio) with lots of Slovaks, Hungarians and Poles but scarcely noticed any ethnic diversity as a kid. It was only years later, in 1982, as a college student in Luxembourg, that I first thought of "Central" or "Eastern" Europe as a distinct region. For our spring break that year, three friends and I rented a car and drove it from Luxembourg to the Black Sea, passing through Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria en route, and then Yugoslavia and Austria on the way back. I wrote in detail about that road trip in a two-part post: “Spring Break With the Ceausescus.” The trip came at arguably the height of the Cold War (with both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in power), and it was an eye-opener. Looking back, it was probably because of that trip that I chose to study international relations at Columbia University. I opted for a concentration in "East European" studies and that's how it started.

What is it about Central Europe you find so interesting?

I guess I was first drawn to the literature, more specifically the great Penguin book series in the 1980s edited by Philip Roth titled "Writers from the Other Europe" (I wrote here about how important that book series was to me: “Remembering That Other Europe.”) It was a selection of 20th-century Central European writers, like Milan Kundera, Danilo Kiš, Tadeusz Borowski, and others, that blew me away. And then came the movies from that period, including the Czechoslovak New Wave and the "Man of Marble" films from Polish director Andrzej Wajda. What attracted me then, and still attracts me now, is the "different-ness" of the region. By that I mean, firstly, the strange communist system that was so different from anything I'd seen before, and then, later, the deeply inspiring anticommunist revolutions of 1989 and transition to democracy in the 1990s and early-2000s. As I've lived here and learned more of the region's culture, history and diversity, I've discovered new interests. I'm now into architecture, history (including WWII, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Holocaust) and cycling. Part of the reason for this blog and my travel writing is to share my interests with others who are similarly fascinated by the place.

So, why Prague and not some other city?

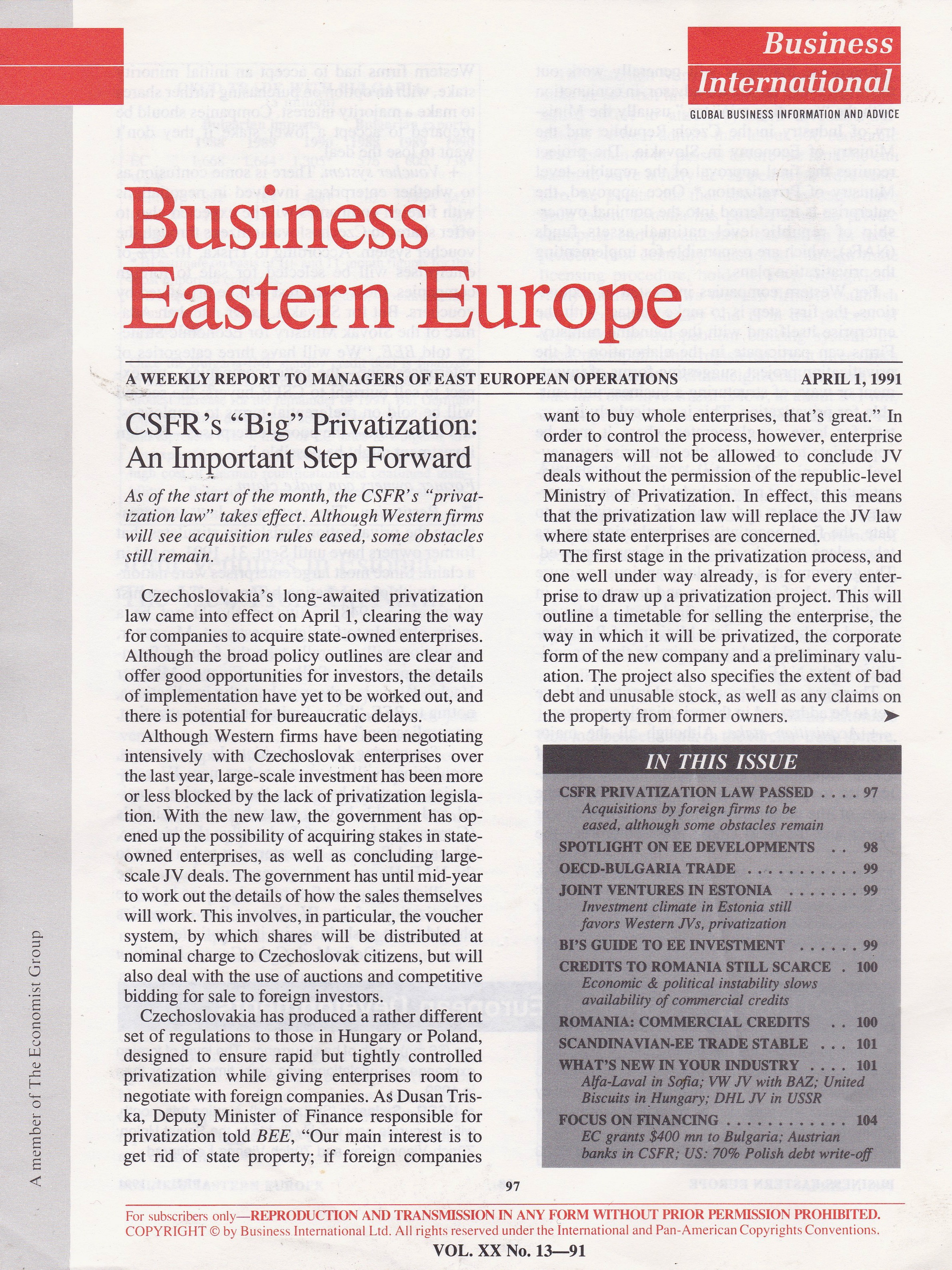

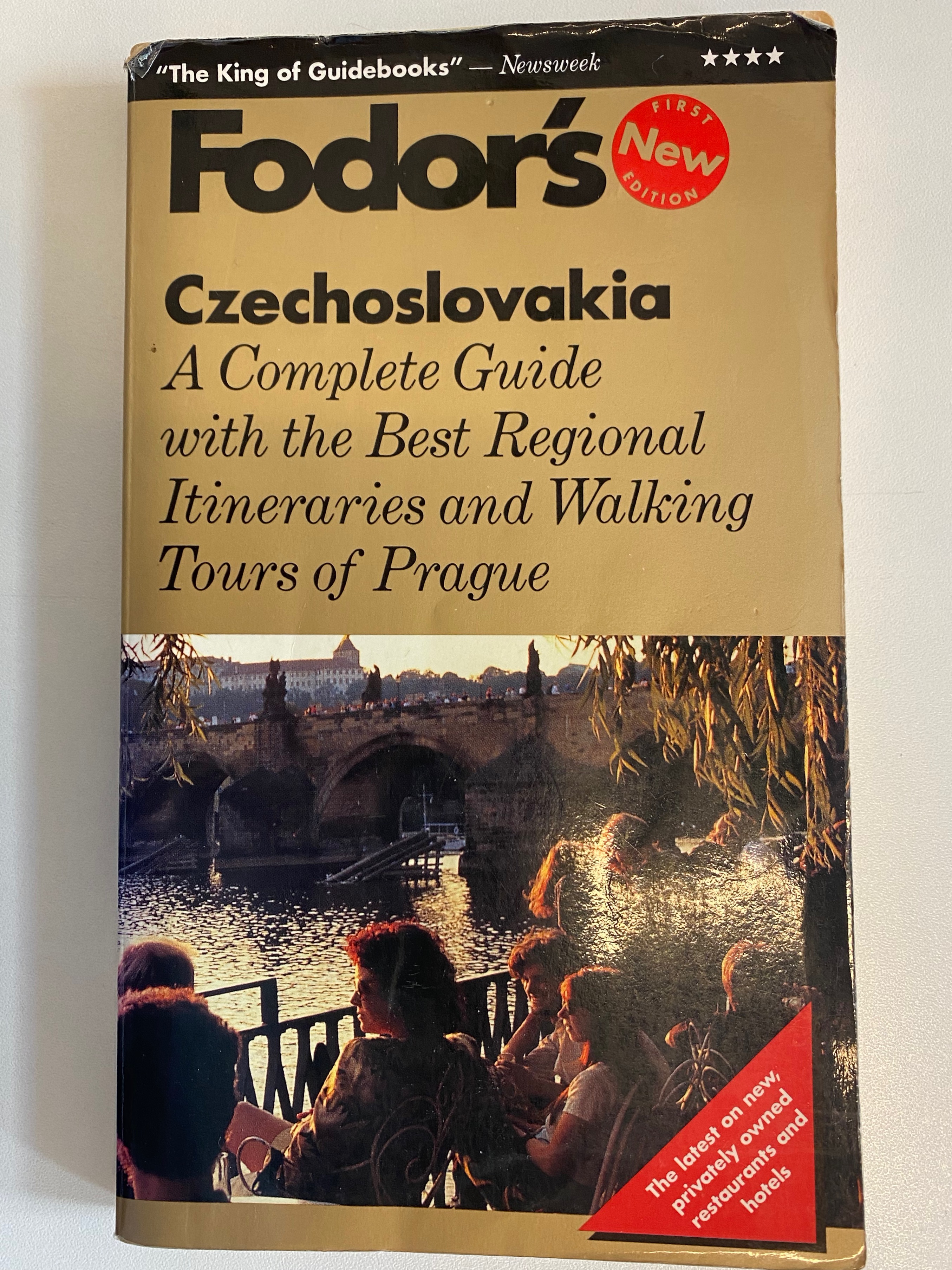

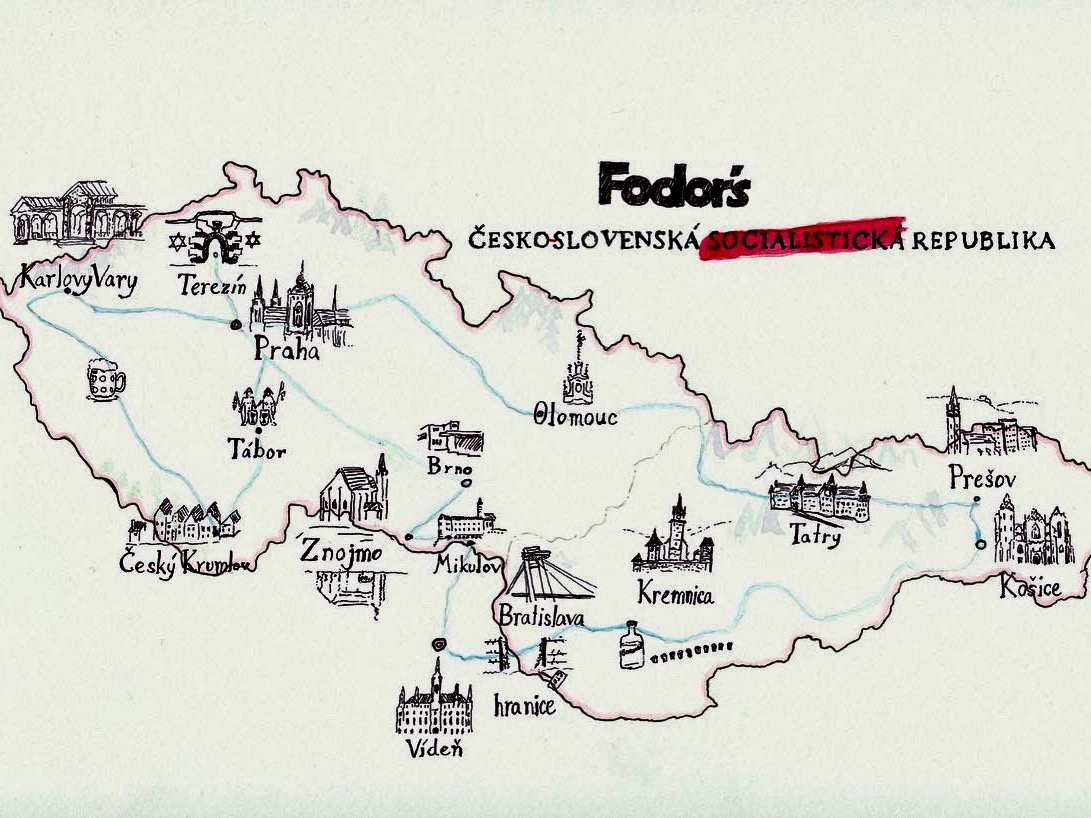

During that first early road-trip as a student to Eastern Europe in 1982, we weren't permitted to travel to Czechoslovakia. It was too soon after "martial law" had been declared in Poland (December 1981), and the Czechoslovak authorities were not letting many (or any) Western tourists in. Maybe because I couldn't see Prague on that trip, the city retained some fascination for me. I finally did get to Prague for the first time in the summer of 1984 on a trip to Europe to visit my college roommate (who was studying in Poland at the time). I've written in the past about how harrowing that first trip to Prague turned out to be: “The Case of the Missing Roommate.” After graduating with my M.A. in 1986, I took a job as a journalist with a small media company, Business International, that covered Eastern Europe from an editorial office in Vienna. As luck would have it, I became the bureau's "Czechoslovak" correspondent and traveled to Prague several times in the late-'80s. I left Business International in 1991 with a contract to write a book on Eastern Europe for the Economist. For that project, I could choose to live in any Central European capital. I briefly considered Warsaw and Budapest, but because I had gotten to know Prague so well by then, that's the city I chose.

Why should we say 'Central' and not 'Eastern' Europe?

Whether to refer to this part of the world as "Central" Europe or "Eastern" Europe is a semantic (and geographic and cultural) minefield. As an author for books like "The Lonely Planet guide to Eastern Europe" (with chapters on Poland and the Czech Republic) and "Frommer's Eastern Europe" (ditto), I've had my share of confrontations over the years with irritated Czechs, Poles, Hungarians, etc, who insist their countries are part of Central -- not Eastern -- Europe (a term they link with communism and the 'Eastern bloc'). Guidebook publishers have traditionally preferred "Eastern Europe" (though this has changed in the past few years) since the book-buying public is more familiar with that usage (publishers are in the business of selling books). For my website, I've chosen to go with "Central" Europe. First off, I'm based in Prague and it's more accurate from a geographic and historic standpoint. Secondly, Central Europe -- as broadly defined by the borders of the former Habsburg Empire -- is closer to the spirit of my website.

How did you go from journalism to travel writing?

I don't think anyone ever starts out to be a travel writer. It something you fall into. I had no intention of becoming a travel writer when I moved to Vienna in the mid-1980s (or to Prague in 1991). As I wrote above, I began as a journalist in Vienna in 1986 for Business International (BI), which was bought out during my time there by the UK's Economist Group. I’ve written several times about Business International and what a strange place it was to start a journalism career: most recently last year in a five-part post, “Introducing INTER,” after I discovered the Czechoslovak secret police considered BI to be a front for the CIA (and me personally a promising recruit for Czechoslovak intelligence).

After BI, I worked as an editor and writer for The Prague Post, Bloomberg News and then Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. I only decided to become a travel writer after I realized my day job at Radio Free Europe didn't afford me much opportunity for travel or professional growth. Travel writing is one of the few avenues that still allows freelancers to develop as a writer while also earning a livable wage.

What's it like writing a guidebook?

Whenever I tell people I'm a travel writer, they often respond with some version of "that's my dream job." People are curious about how the system works, whether writers take money in exchange for favorable reviews, and whether you make a living from it. The short answer is yes, I enjoy it; no, I never take freebies to include places; and yes, with careful budgeting, one can make a living. The longer answer, though, is more nuanced. Writing a guidebook is an incredibly complicated undertaking. To do it well requires a fetishistic attention to detail, broad historical knowledge, the ability to write concisely (but in an entertaining way), and a monk-like tolerance for spending days, even weeks, on your own. It can get lonely on the road.

On the downside, as a freelance travel writer, you're not just the author of your own text, but also your own marketer (pitching your expertise to overwhelmed editors), your own travel agent (booking trips that can last as long as eight weeks) and your own bill collector (dinging editors for "lost" payments in strings of frustrating emails). Thankfully, most of my publishers are good about payment, but the "check is in the mail" syndrome is a dispiriting fact of life all freelancers must deal with. The positives outweigh the negatives, and travel writing has helped me to deepen my knowledge of the countries and cultures I'm interested in, develop new interests, and hopefully grow as a person and writer.

What does the future hold for travel writing?

Ever since smartphones came into our lives more than a decade ago, people have been sounding the death knell for print guidebooks. In spite of that fact, though, they're still going strong. The Covid years were brutal for freelance writers (with no work and no paychecks), but since the lockdowns ended in 2022, I've been busier than ever. One consequence of Covid was that it left many guidebooks -- and much of travel content generally -- out of date. Publishers are scrambling to update their travel books and websites, and work -- for the time being -- is plentiful. For the more distant future, I'm guardedly optimistic but technology poses an ever-present threat. There will come a time soon when artificial intelligence (AI) generates a lot of travel content. Already, there are reams of travel sites on the web that are "written" by bots. My hope is that publishers like Lonely Planet and others remain committed to paying real humans to research destinations on the ground.

Last question: Czech Republic or Czechia?

It took me a while to warm up to it, but I'm now firmly in camp "Czechia." Neither name will ever be quite as awesome as "Czechoslovakia," so what difference does it make?