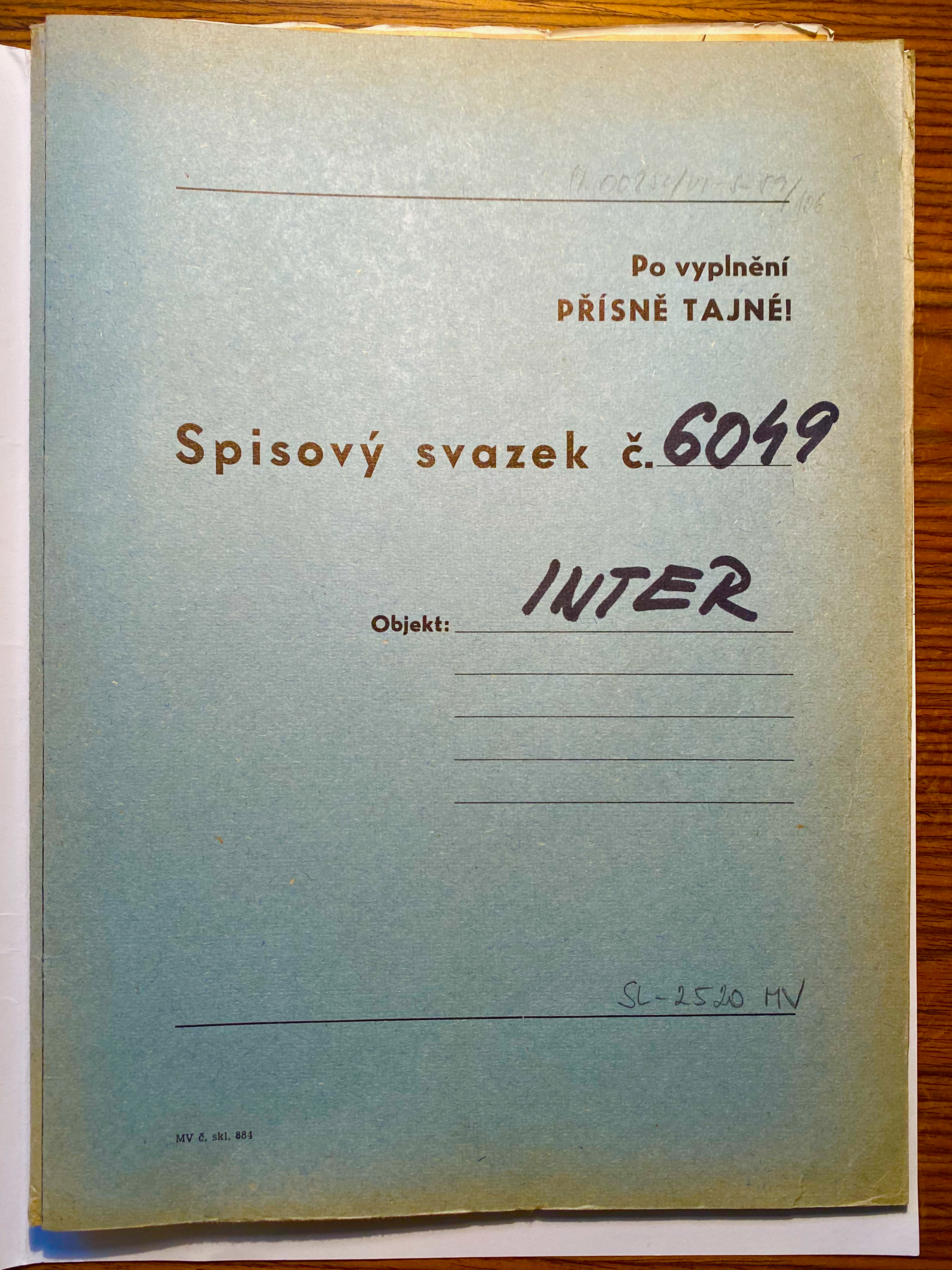

This unlikely tale about me and "INTER" begins in 1986, when I first moved to Vienna to work as a journalist for a small publishing company called Business International (BI). The company specialized in covering the former Eastern bloc, and I became BI’s Czechoslovak expert. It was my job to travel to Prague, Bratislava and other cities to report on significant developments that might be of interest to our readers, mainly managers of large multinational companies who sold products across the Iron Curtain. From 1986 to 1990, I traveled to Czechoslovakia around a dozen times.

BI was my first employer out of grad school and I was still wet behind the ears. Though I had specialized in Eastern European studies at Columbia, I was still learning how centrally planned economies worked and I spoke only rudimentary Czech. To help me in my reporting, BI retained the services of a Prague-based stringer named Arnold. I’ve written previously about Arnold on this blog (link here). It was his job to arrange my accommodations as well as set up my meetings with Czechoslovak ministers and company directors. He also served as my driver and translator.

Arnold was one of several Eastern European nationals whom BI employed back then, and I and my fellow co-workers would occasionally discuss among ourselves whether these individuals might be undercover agents for the Eastern bloc. No one knew for sure. It sounds naïve in retrospect, but it seemed inconceivable that our company would ever knowingly employ an operative from the east.

Traveling across the Iron Curtain back then was no easy feat. For my reporting trips, I'd first need to spend hours waiting in line at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Vienna to secure a visa. Once underway on a trip, the trains were excruciatingly slow and the waits at international crossings -- as hostile border guards searched the cars for contraband -- often took the better part of a day. Even something as simple as booking a hotel room was tricky. Arnold's assistance on the ground in Prague was crucial to my success. I was always cautious in my behavior around him, but I depended on him. We weren’t friends, exactly, but I regarded him as a colleague and believed we were working toward common aims.

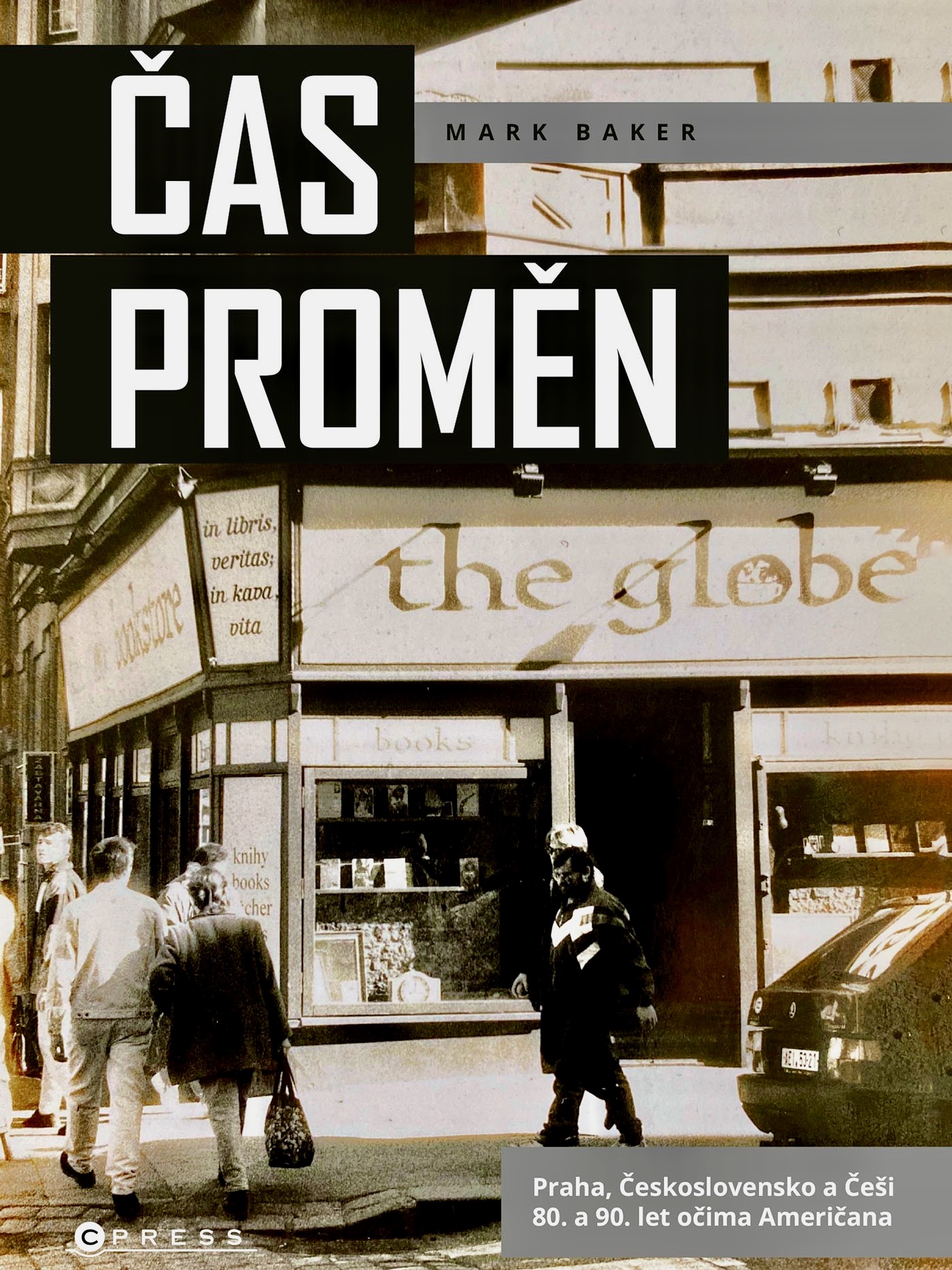

After the fall of communism in Czechoslovakia in 1989, I fell out of touch with Arnold. In 1991, I resigned from Business International and relocated from Vienna to Prague. I only ever saw him again on one occasion, in 1993. He was working as a translator for a German television network and accompanied a film crew to cover the recent opening of a bookstore and coffeehouse, The Globe, that I had started in Prague with four other friends. We briefly caught up and traded chit-chat. He seemed to be doing well.

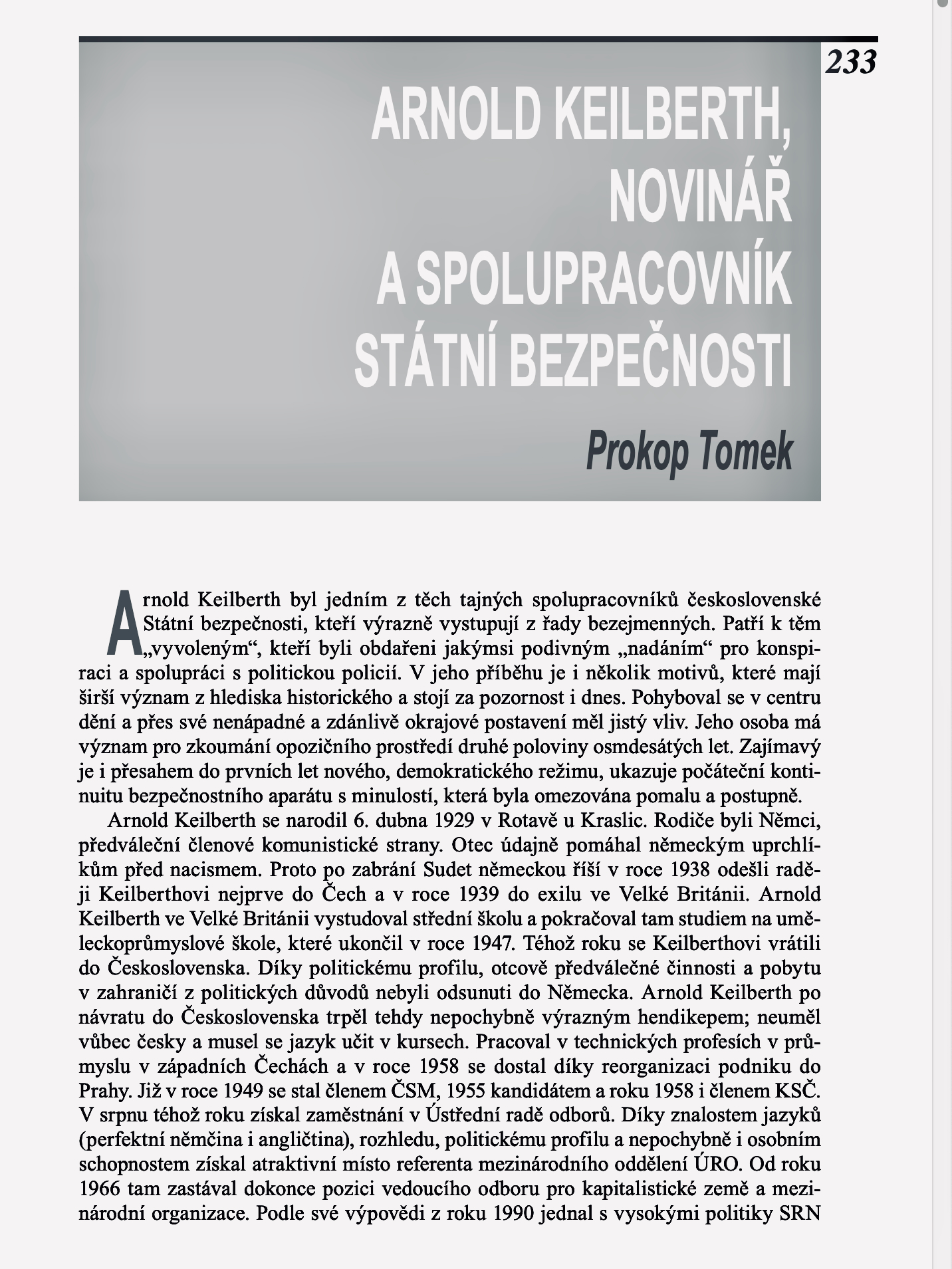

Fast forward several years later, to 2014. I was sitting at my computer in my Prague apartment one evening and wondering what had happened to my former colleagues from back in the day. I thought about Arnold and wondered whether he might still be alive (he would have been in his 80s by that point). I typed his named into the search bar and hit return. At first I didn’t see any information about him. As I scrolled through the search results, I spotted a suspicious-looking link to a PDF report on Arnold written by a researcher at the Prague Institute of Military History named Dr Prokop Tomek. I clicked on the report. My blood froze the moment I read the title: “Arnold K*, Journalist and Collaborator with the Czechoslovak Secret Police."

Do I Have a File?

After reading the report and learning many things about Arnold I never knew, including that he enjoyed a long career as a paid collaborator with the secret police and passed away in 2001, I quickly realized I was likely one of his many espionage targets. If the Czechoslovak secret police hadn't created a separate surveillance file on my activities, they would certainly have reported on me as part of Arnold’s file.

Fully expecting to locate my own file, shortly after that, I applied to the Czech Interior Ministry for permission to view any materials they might have on me. My request took several weeks to process but ended in disappointment. After searching the archives, the Czech authorities told me that my name didn’t appear in their materials and if I ever did have a file, it would probably have been lost or destroyed after 1989.

And that was the state of play in early-2020, when I began to research and write a book about Czechoslovakia in the 1980s and ‘90s called “Čas proměn” (Time of Changes). For the book, I wrote extensively about Arnold and my trips to the country and recounted many strange adventures from those journeys. These included a bizarre evening in 1987, when my room at the Intercontinental Hotel in Prague had been broken into, and of several train trips in the late ‘80s from Vienna to Prague when I strongly suspected I’d been surveilled by Czechoslovak agents. Once I read Dr Tomek’s report about Arnold, I naturally assumed those adventures were linked to him and the StB. Without a file to verify my stories, though, I was left only with my own speculation (and good tales to tell for the book).

During the writing process, I reached out directly to Dr Tomek and he confirmed what the authorities had told me earlier: I didn’t have a file. He theorized that Arnold must have enjoyed strong support at high levels and that most of the materials on him, including anything with my name on it, would have been shredded after 1989 in an effort to shield his identity. In the end, I wrote in my book what I believed at the time to be true: Arnold was certainly an informant and although I myself probably didn’t have a file, because of my association with him, I was likely the target of StB surveillance myself.

Čas proměn was published in July 2021. As a way of thanking Dr Tomek for helping me, I sent him a signed copy. I had no idea what was coming next.

A Surprise Email

A few months later, on a trip back to Ohio over the Christmas 2021 holidays, I happened to check my email one evening and spotted a message from Dr Tomek in my inbox. I assumed he was probably writing to thank me for the book, and I opened the message. Indeed, the email was about Čas proměn, but not in any way I was expecting.

Dr Tomek wrote that he enjoyed the book but after reading it, he’d become suspicious that a person with my background would not have had a surveillance file. He said he then sent a request of his own to the archives and discovered that I actually did have a file – and an extensive one at that. As a way of explaining why the authorities were only now able to locate my file, he said the archive’s screening capabilities had improved considerably in the past few years.

He then added, cryptically, that after reading through the materials, he had discovered a long-hidden StB plot to try to recruit me. He sketched it out briefly in a few lines as follows (reworded slightly to improve legibility):

“The Czechoslovak intelligence planned in 1989 to recruit you as an agent (secret collaborator). The final plan was dated November 2, 1989 … They planned to ‘plant’ an agent: an attractive girl with the code name of INA. The operation should take place in Bratislava, during the last two days of your November 1989 stay in Czechoslovakia. Arnold was to lead you into this trap … The main reason for recruiting you would be to spy against Americans in Austria … “

Spy against Americans in Austria? I nearly fell over in my chair.

To provide a taste of what was lurking in the documents, he attached several photographs, including the spooky looking surveillance photo at the top of this post. The photo, taken by a hidden StB cameraman, is dated June 29, 1989, five months before Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution. In the photo, Arnold and I are shown walking toward a building in the Prague neighborhood of Žižkov. I had no particular recollection of that photo or the day; I certainly had no idea at the time I was being watched so carefully.

Dr Tomek said that my file read “like a movie” – what he meant was a Cold War thriller.

What Do I Do Now?

Dr Tomek’s email had arrived out of the blue and rattled me. I found it hard to think about anything else. Not only did I discover for the first time that I had a file, but that I was apparently being sized up to work for Czechoslovakia's secret police to spy on Americans. It felt totally unreal.

The email was big on titillating points, but short on explanation or context. To learn more, I would have to sit tight until I could see the materials for myself in a month’s time. I was reasonably certain I had never done anything improper on my reporting trips (and I was certain I never spied on anyone), but I also knew that files like these could be easily manipulated and embellished.

In the following days, as I thought about the piles of pages awaiting me back in Prague, my mood fluctuated up and down. On the plus side, I felt somehow vindicated that my work as a reporter had caused a stir among officials on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In the past, when I was told I did not have a file, I felt an odd pang of disappointment. I also felt reassured that the stories I told in my book actually happened (and weren’t figments of an over-heated imagination). Indeed, Čas proměn still holds up well. The only difference was that the system was even more sinister than what I wrote about.

On the negative side, I dreaded the prospect of going through the file and discovering that close friends or colleagues had reported on me. I wasn’t sure I could handle that knowledge. I also felt embarrassed for having been so naïve. And I felt renewed anger toward Arnold. I had known for years now that Arnold had worked for the StB. In my book, though, I bent over backwards to try to explain his own complex motives for having served the regime so loyally. I felt like I’d been double-crossed. (After having now read my file more closely, my attitude toward Arnold has moderated a bit. In his defense, it looks as if he never wrote anything about me that was especially malicious. In many respects, he was simply doing his job.)

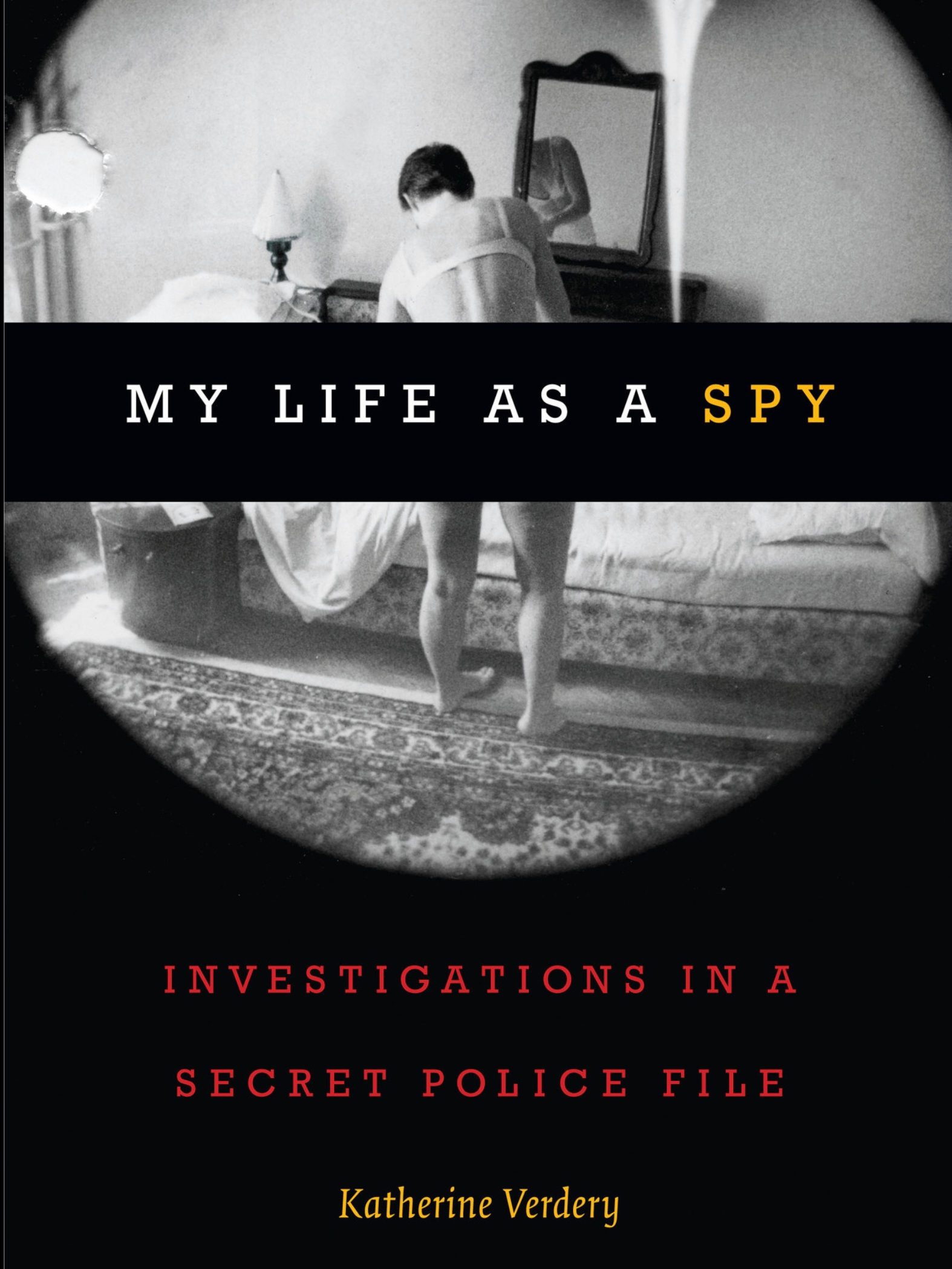

To help process this mix of emotions, I sought out books written by other authors -- journalists and academics – who, like me, had been spied on in Eastern Europe. One of best was Katherine Verdery’s, “My Life as a Spy,” in which she recounted her experiences as an American researcher in Romania in the 1970s and ‘80s and of being surveilled by the country’s notorious “Securitate.” I wrote a post for this blog about her book here.

Verdery’s book, in particular, helped me to realize that my experiences (and my mixed reactions to them) were "normal." Every foreign journalist, academic or diplomat in the former Eastern bloc was surveilled to some degree and would have had a file. In addition, people from all walks of life in Czechoslovakia -- and all across Central and Eastern Europe -- were routinely and unfairly reported on, both by the official security services as well as by family members, neighbors, friends and colleagues. There was no inherent shame in having a file. Indeed, any shame attached to those who meticulously collected the notes.

Reading Verdery’s book gave me the resolve, if that’s the right word, to confront and write about my own file. In truth, I could hardly wait to get my hands on it.

(In Part 2, I write about visiting the archive and reading my file for the first time. Click here to go directly to Part 2.)

*I've chosen not to use Arnold's full name for this series.

You say that you don’t use his surname in order to protect his family, yet it’s clearly spelled out in the photo 🙂 what a cool story! I smell movie rights being sold….

🙂 Thanks. No movie rights yet, but still waiting!

Wonderful reading, Mark! I especially loved “has an eye for attractive women, but doesn’t seem to get very many.” Of course, this could have applied to almost any of us at the time…

🙂 I mean what 27-year-old guy doesn’t fit that profile in some way

Having had my own experiences with secret police back in my home country, I read this article with real excitement and a lot of mixed feelings; it brought back some old memories from my life under communist regime… I’m looking forward to reading part 2. Btw, when will your book “Cas Promen” be available in English?

Hi Bozena, It’s funny but there is nothing in my own file about my trips to Poland or visiting you in Krakow. Either it was lost or they just weren’t interested. 🙂 I will be interested in your impressions about the rest of the stories. About Cas Promen, I will definitely publish in English and incorporate the new information into the updated book. Thank you for leaving a comment! Mark

My pulse went up as I was reading this. I remember when I got my files from the Hungarian archives, pretty shocking. I am so much looking forward to reading your book in English!

Pingback: The Inter File – Transitions – Travel News

Mark, did you get any explanation why Mark Baker and INTER can’t be found in the published index files? Other aliases you mention can be found, though some without the clear name.

https://ibadatelna.cz/search/#

I’m not sure why there might be an issue with finding my name and INTER in the published index. Even when I first went looking for my file in the mid-2010s, I was told that it didn’t exist. There might be a lag in what’s available in the published files, or it might simply be something to do with my particular file. I guess this would be a question for the archives? Thanks for reading and leaving a comment.