It was the spring of 1982 – the time of “Every Little Thing You Do is Magic,” “Tainted Love,” and “Don’t You Want Me (Baby)” -- and I was a student in Luxembourg on my junior year abroad. I’d never been to Europe before. Compared to Ohio, where I had grown up and attended school at Miami University (the one in Ohio), Luxembourg was the most interesting place I’d ever seen before in my life.

Luxembourg seemed to have it all. It was picture-postcard beautiful and livable at the same time. The place was stuffed with pubs where no one cared how old you were; cafes where people actually went to drink coffee (this was way before Starbucks); a big, central train station where you could hop a ride on a whim to anywhere on the continent; and city transit buses that people actually rode on.

It felt light years away from the classic Midwestern suburb I grew up in where everyone drove everywhere and social life (for me at least at the time) seemed to center around the local McDonald’s and the mall. It was also a needed break from Miami U., with its fraternities and sororities and high-school overachievers run amok. After going to school there for three years, I had yet to find my crowd. Even though the school I attended in Luxembourg was actually a Miami branch campus (with mostly fellow Miami students), I found it much easier to meet like-minded people and make friends.

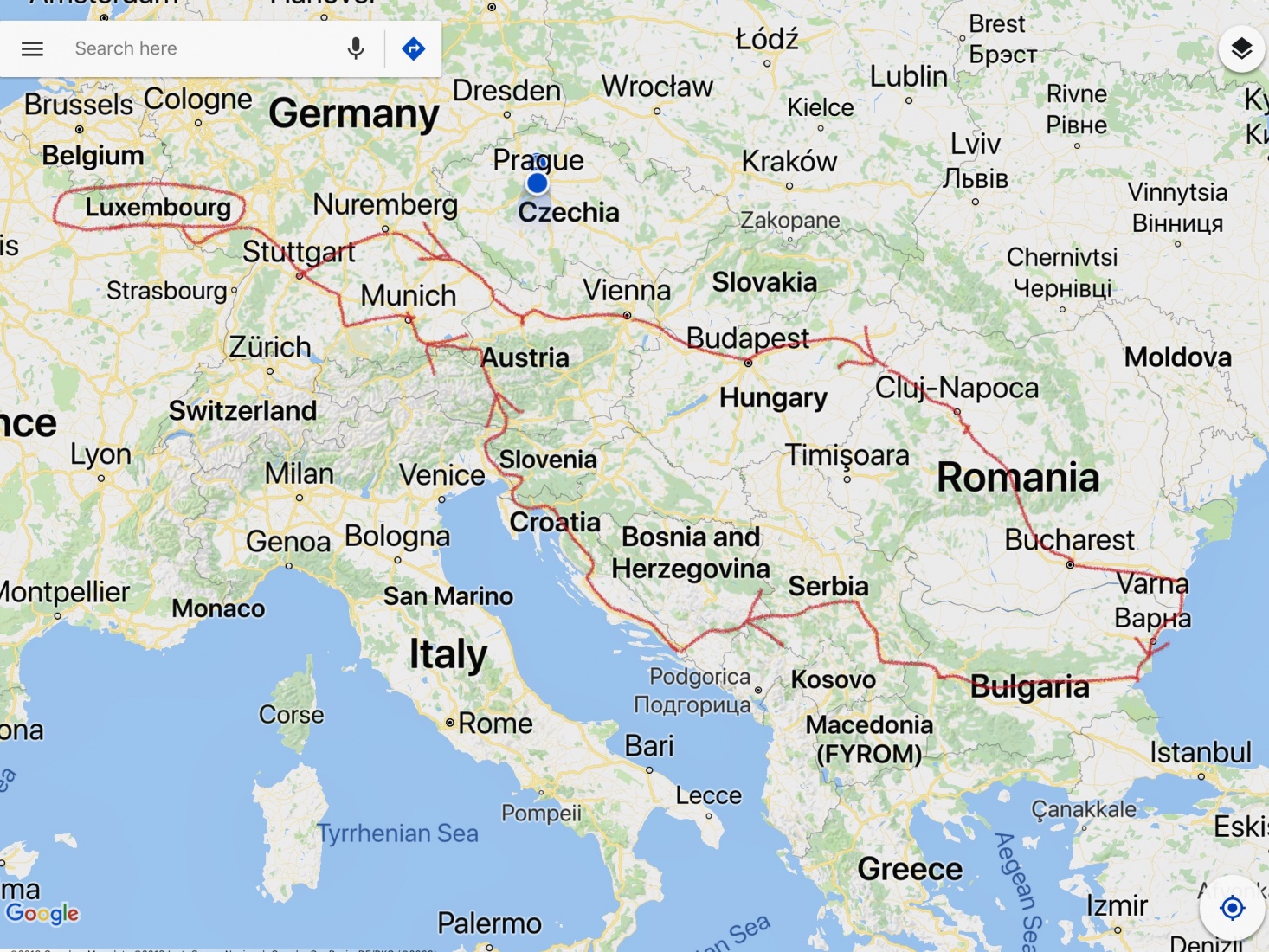

When I look back on how events conspired to land me in Europe for most of my adult life, the first step on that journey was obviously my decision to go to school that year in Luxembourg. When I trace the path, though, that eventually led me to Central & Eastern Europe (and on to Prague), the credit (or blame) would have to go to a spontaneous, ill-informed, crazy-in-retrospect road trip that three friends and I made that spring from Luxembourg to Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia.

To set the stage for that trip, it's worth keeping in mind that relations between East and West at that time were not exactly cordial. The staunch, Cold War warrior, Ronald Reagan, was in the White House. His British counterpart, Margaret Thatcher, was at 10 Downing Street. Mikhail Gorbachev was still a junior member of the Soviet Politburo and wouldn’t become First Secretary of the Communist Party until 1985. Gorbachev’s policies of “glasnost” and “perestroika,” which would pave the way for a rapprochement between East and West and even the rollback of communism in 1989, were still off on the distant horizon.

In fact, history seemed to be moving in the exact opposite direction. Just that previous December (1981), the hard-line government in Poland under General Wojciech Jaruzelski had declared martial law in an effort to crush the independent-minded Solidarity trade union. There was real fear at the time the Soviet Union was plotting a military invasion – like Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968 – to shore up Poland's regime. Czechoslovakia, for its part, had suspended issuing entry visas for visiting foreigners (I suppose for those reasons, it never crossed our minds to go to either Poland or Czechoslovakia).

Still, the four of us (myself and friends Doug C., Sheila F. and Jerry O.) were already getting a bit restless with the relative comforts of Luxembourg. We’d checked off the classic junior-year-abroad must-sees like Paris, London, Amsterdam, Florence, Rome and Madrid, and had started looking eastward to that “other” Europe, across the curtain.

It’s funny but in retrospect I can’t recall many of our fellow students expressing an interest in visiting the communist Eastern bloc at the time, although I think there were a few. I guess most students were dreaming of Greece or Italy for spring break that year. It's hard to imagine now, but Eastern Europe really was off the map back then. The teachers and admins at Miami University’s European Center probably weren't too happy with our travel plans, but most kept any strong objections they might have had to themselves (they were probably wondering how they’d airlift us out there if something bad happened).

The only exception I can recall was from one of our favorite teachers at the center, a European history professor named Emile Haag. Dr Haag took us aside one afternoon and tried to warn us against the trip (in his heavily accented English, a bit like Henry Kissinger, that lent an extra dose of gravitas to everything he said): “Those (eastern) regimes are very, very hard. You must be very careful” (or something like that). It put the fear of god in us.

Nevertheless, we went ahead with the trip. We rented a red Ford Escort for the journey, and obtained in advance as many of the country entry visas as we could. The Bulgarian visa at the time required an in-person interview – which was actually pretty easy to do since the Bulgarian Embassy in Luxembourg was located just next door to our school. We walked over for tea one afternoon and that was that.

We’d also been advised that Western cigarettes could prove useful in getting us out of almost any jam (just like American soldiers in World War II). This was particularly true, for some reason, in Romania, where the U.S. brand “Kent” had strangely evolved into a kind of alternative currency. The four of us dutifully loaded up the trunk with cartons of Kents, and on an early morning in April, we hit the autobahn bound for Budapest.

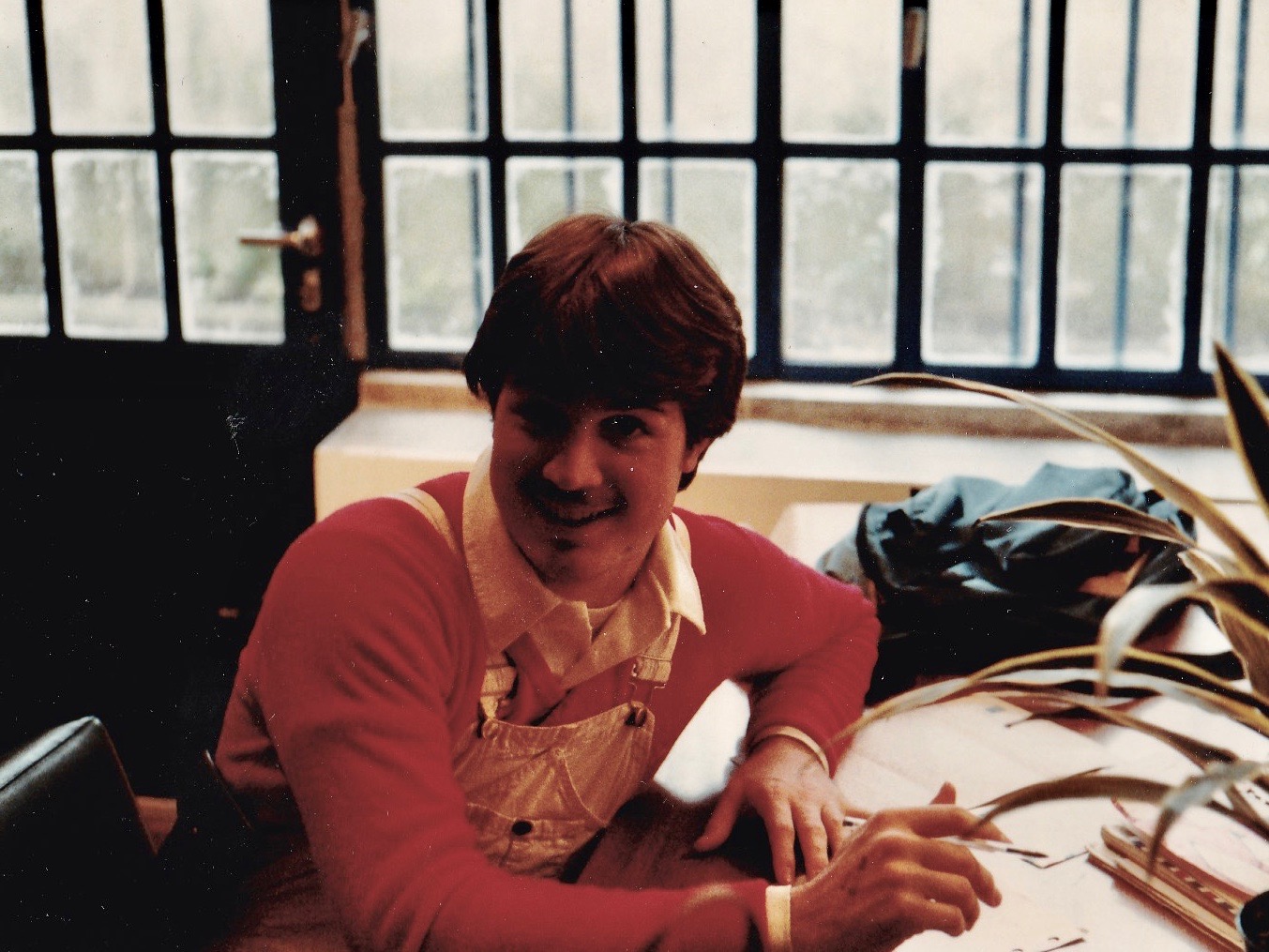

For a writer, I’m a notoriously bad diarist, and when I’m called on to give advice to would-be travel writers and bloggers, I always implore them to keep a diary. I’ve drawn on some of Sheila’s and Jerry’s memories here for this post, but sadly you’re at the mercy of my own fading memory. No doubt Doug, one of the smartest guys I’ve ever met and with a great sense of humor, would have had some amazing stories to share. He tragically passed away in 2005 from a rare form of cancer. He was just 44 years old.

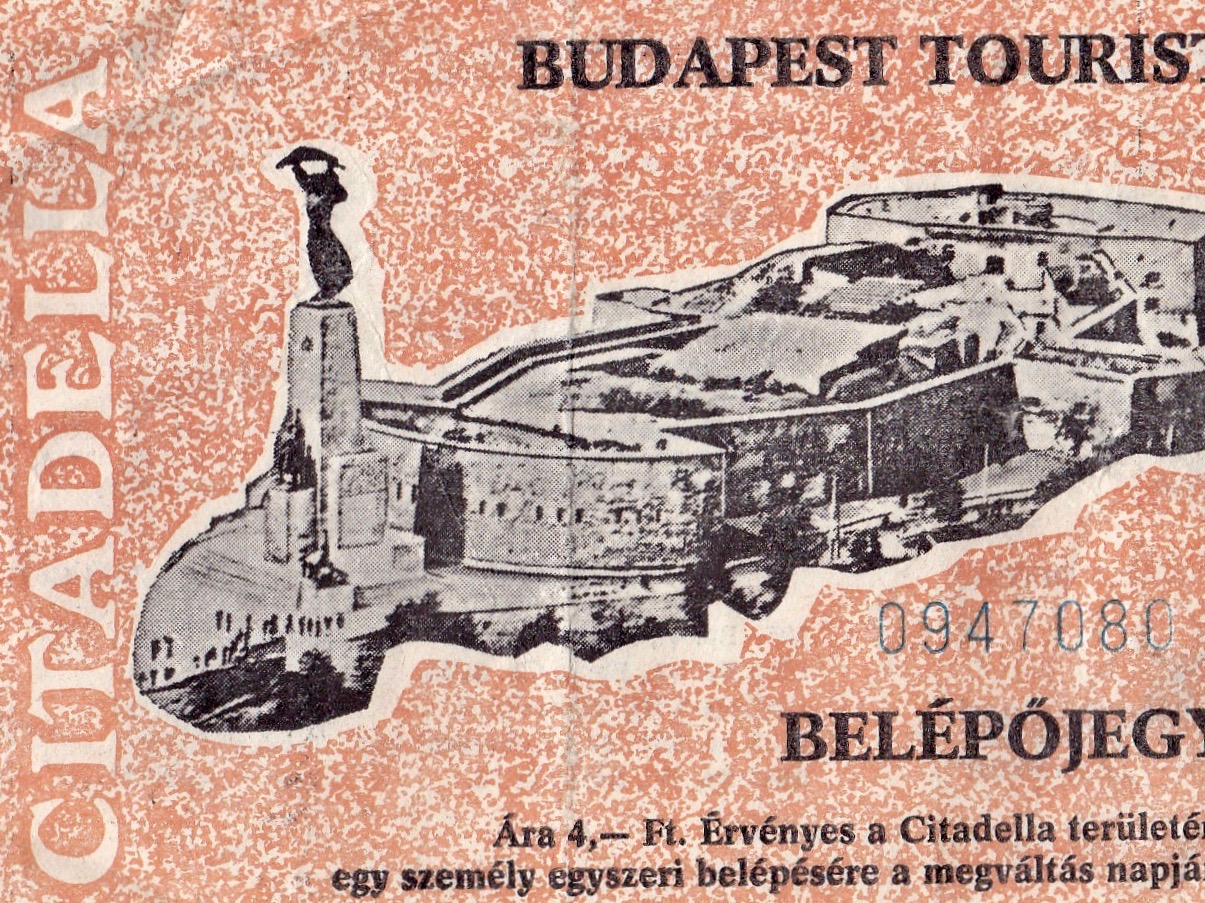

Budapest was a fascinating place, but a rude awakening for the four of us. After coping with relatively easy languages like French, Spanish, or German that we’d studied in high school – or at least could puzzle out some words in – Hungarian was from a different planet. To make things worse, we’d made the long drive down from Luxembourg in one day and arrived after the state-run Hungarian Intourist offices – our hosts – had closed. We spent that first night camped out in our car.

My most vivid Budapest memory – and probably Jerry’s too from an email that he sent me a few years ago – comes from our comic attempts to visit the city’s famous Turkish baths. During that trip, we visited both the more-modern baths at the Hotel Gellért and the older Ottoman-style baths on Fő utca. At the entrance to the older baths, back then, visitors were confronted with a long and bewildering list (in Hungarian only) of the spa's rules, services, and prices. We had no idea what we wanted or how to express it, and were at the mercy of the old ladies who were obviously running the joint. Sheila was the only the female in our group and was separated from us from the start. I still have no idea how she spent that afternoon, but she said she had fun.

I suppose it’s obvious looking back (I was pretty naïve at the time), but we also hadn't realized just how popular the Fő utca baths would be with Budapest’s large and apparently thriving gay community (according to the official propaganda, there were actually no homosexuals in Hungary at all). It quickly dawned on us that we'd accidentally bumbled our way into gay bathhouse.

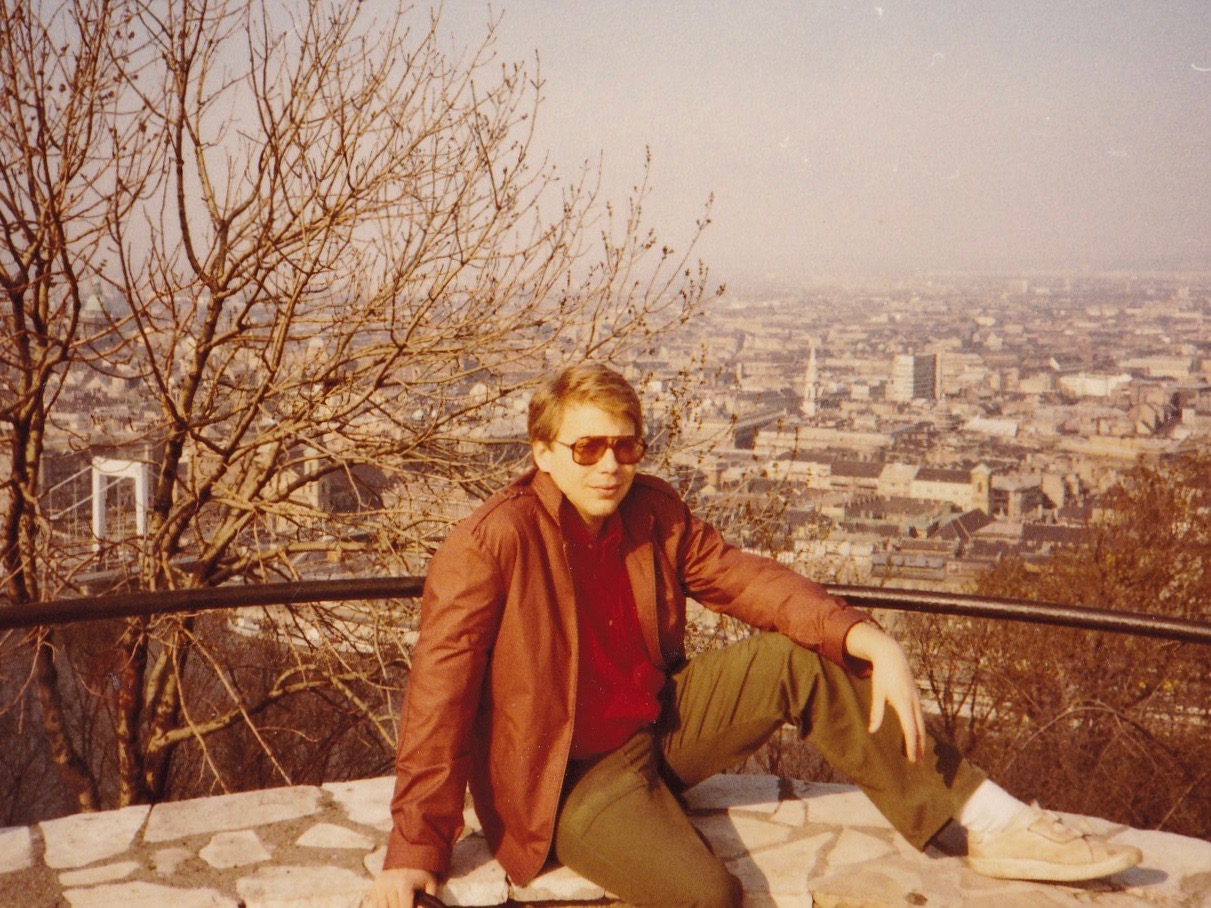

Judging by the dates on the backs of my photos, we spent several days in Budapest, though aside from some surviving pictures of us climbing up the Citadella hill and admiring the Danube spread out below, or rowing in a lake, I’m not sure how we spent the time. I do remember, though, that feeling of exhilaration and satisfaction of being forced to cope in such a foreign-feeling environment. It's something all travelers enjoy on some level.

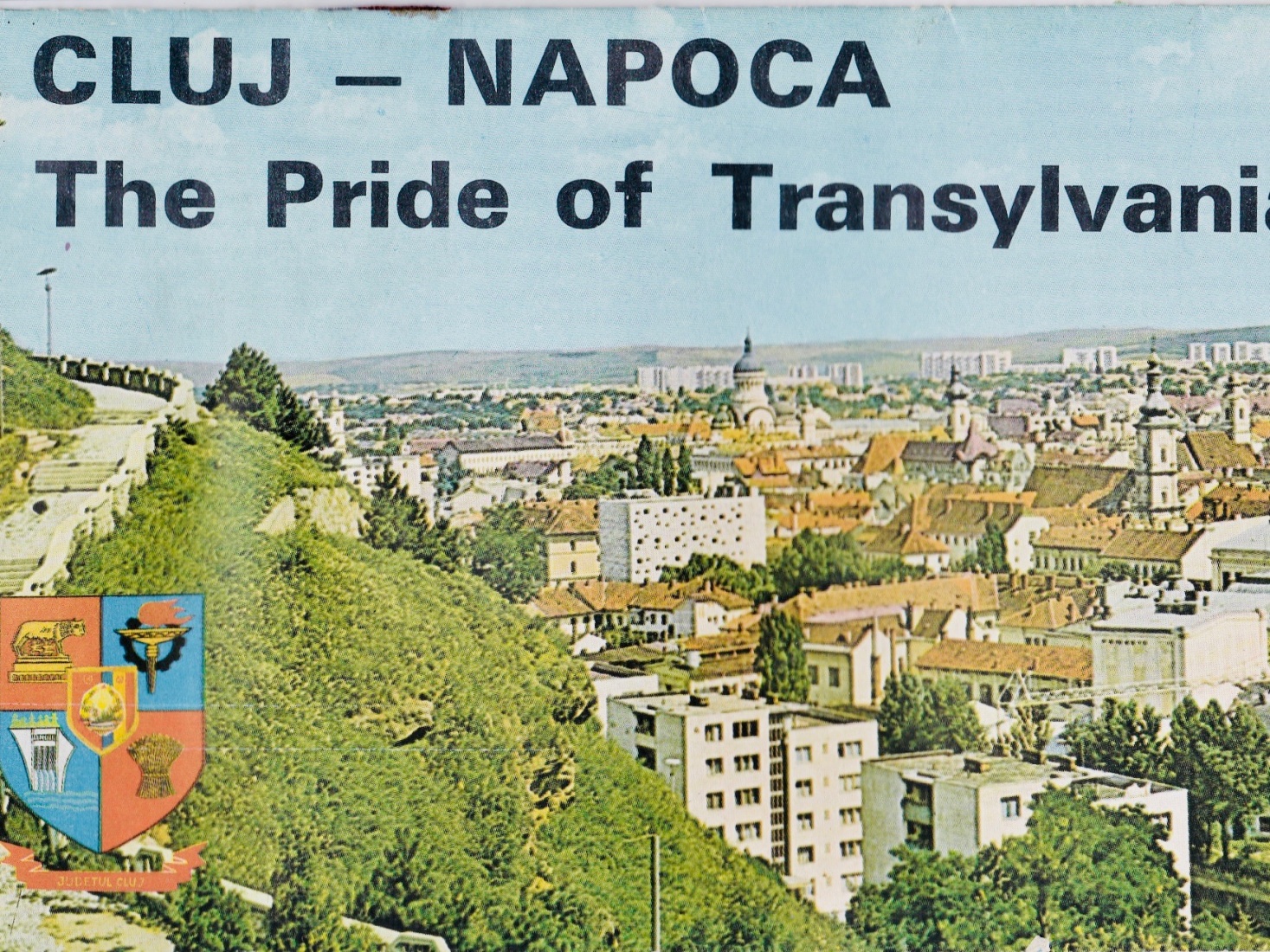

Our next stop was Romania – more specifically, Transylvania. We probably entered Romania near the city of Oradea (though it could have been further south at Arad). We had no real fixed itinerary other than to reach the Black Sea and make it back to Luxembourg, and once we'd entered Romania, we also lost any official support. In Hungary, we’d booked through the state-run Intourist agency, but here, suddenly, we were completely on our own.

The problem was that, unbeknownst to us, Romania in the early-'80s was just then experiencing a serious food shortage that would last at least until 1985 or ‘86. The ruling Ceaușescu regime was recklessly trying to break its dependence on foreign loans by exporting everything – including anything you could eat – in order to prepay the loans. The regime was literally taking food out of the mouths of its people in order to do this.

Compared to Hungary in those days (which appeared to be quite “normal”), Romania felt isolated and badly underdeveloped. As we drove along a lonely highway through the center of Transylvania toward the city of Cluj-Napoca and searched for a place to eat or sleep, we realized we might be in some serious trouble.

And that’s when those Kents came through.

Along the highway, we’d passed what looked to be a modest campground with some holiday bungalows for rent. This still being April, the place appeared to be closed, but a dim light was burning in the main building. There was hope.

We knocked on the door and explained our situation (in English) to our obviously surprised would-be hosts ("Hey, the Americans are here!"). They were friendly under the circumstances, but also adamant they were closed for the season and there was no possibility of staying overnight. (I later learned the Ceaușescu government had greatly discouraged contacts with foreigners, and even our presence could have gotten them into trouble, but we had no clue about that back then*). That’s when we had the idea simply to drag them over to the car, open the trunk, and show them the tobacco bounty we had in store.

I still remember the look in their eyes as they saw the cartons of cigarettes. We didn’t know what the going rate for a bungalow would be at the time, but we offered one carton (10 packs). Friends would later tell us, laughing, that we had badly overpaid.

In the end, we had our own space (without running water or electricity, but a clean bed) and our hosts even brought over a filling meal of pork and potatoes (or at least that’s what I remember). It was delicious. After dinner, we went out into the magical hills above the cabin, under a nearly full moon, to tell Dracula stories and marvel at the fact that we'd made it to Transylvania. I can still drum up that feeling of excitement to this day.

The next day, as we followed the signs south over the Carpathian mountains en route to Bucharest, we saw with our own eyes the extent of the food shortage. In the city of Turda, we stopped at what looked like a small food shop in the center of town. We perused the shelves, which were completely empty except for cans of “horse” mackerel (fish) and Russian sparkling wine. I remember the look in the shopkeeper’s eyes as she told us, in English, that they had "nothing."

After Turda, we stopped over at the beautiful Transylvanian town of Sighișoara, where Doug snapped the photo at the top of this post of Jerry, Sheila, and myself walking up the hill toward to the Scholars' Stairway (the Old School steps). Today, that photo sits on my office wall and I see it every day.

I don’t remember if we made it all the way to Bucharest that night or stayed somewhere in between (if we made it one drive, that would have been a very long day on the road). Once in Bucharest, though, we managed to find another campground/bungalow situation. I'm not sure if we played the same trick with the Kents or not, but as I recall we had a great spot, near a lake and with an eye-catching view of the Casa Scînteii, a communist-era skyscraper, just nearby.

I write about Bucharest frequently these days for Lonely Planet and other publications, and I often find myself in that same neighborhood (under different circumstances, of course). I’ve never been able to locate those bungalows, but if they still exist they would be somewhere near to where the Băneasa Shopping Center is today.

Needless to say, our red Escort with its Luxembourg plates and four students inside, drew the attention of passers-by everywhere we went, but nowhere were the reactions more memorable than in Romania. People would frequently point to the "L" on the back of the car and ask us what country it stood for. Most people guessed Liechtenstein, and seemed truly amazed to find out it was, in fact, Luxembourg. It was as if to ask: "Why would anyone from Luxembourg ever come to Romania?"

One day an old man at the Bucharest campground stopped me on the street and asked in a few halting words of English where I was from. When I said “America,” he got a rather confused look in his eye. “America?” he asked, quizzically, as if he’d never heard of the place. “Brazil?”

Click here to go directly to Part 2, where I follow up with our trip along the Black Sea coast and slow journey back to Luxembourg.

*Helena Drysdale's sad, gut-wrenching book "Looking For George" spells out clearly the risks local Romanians ran in the 1980s in any interaction, no matter how innocent, with foreigners.

Fascinating memories and tales of your adventures Mark. Love reading these stories. Funny to recall that back in the early eighties I might have thought about visiting Eastern European neighborhoods as well…but only on the east side of Cleveland at that time! Hope all is well.

Hi Jerry, Thanks for reading and leaving a comment. I’d love to go up to Cleveland sometime and write about those Eastern European neighborhoods. While I was in Slovenia, every time I mentioned the word Ohio, people would remind me that Cleveland is the second biggest Slovenian city after Ljubljana. All the best, Mark

Mark, just came across this two part series and really enjoyed. Love the photos too. Brings back a lot of memories. I was no better with Kents when I traveled to Romania in July 1987. Bought them from the hard currency shop in Budapest before entering Romania. Of course, if you are a naive young middle class American, you are not wise in the ways of bartering, haggling, and discretely offering them (the guide books don’t address this issue! nor should they have to, probably). I ended up giving loose cigarettes and a few packs away on a street in Bucharest. After a guy took a pack, he said in English, “you know, things are really bad here”…you don’t say, says the kid giving out Kent cigarettes as if he were a WW II GI giving out gum…