I seem to be a lifer when it comes to Central & Eastern Europe. At least that’s how it must seem to my family and friends back home in the United States. It’s hard for me to explain, sometimes, how a relatively "remote" part of Europe can seem so compelling -- or at least interesting enough to plan a professional career and the better part of a life around.

I’ve already written here how it was a junior-year-abroad program in Luxembourg – which included a spring break trip to the Black Sea -- that first brought to my attention the countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain. That journey led me to apply to a master’s degree in International Affairs at Columbia University (and its Institute on East Central Europe). It was around then, too, that I traveled to Prague for the first time and experienced the bizarre, Kafkaesque charms of that city firsthand. I wrote about that fateful visit in one of the earlier stories on this blog: “The Case of the Missing Roommate.”

Just maybe, though, it was an obscure course -- an elective -- on “Contemporary East European Fiction & Film” that I took at Columbia in 1985 that sealed the deal for me in Eastern Europe -- and looking back now probably sealed my fate as well. The course was taught by Ivan Sanders, a highly respected translator of Hungarian literature, and was meant to present a generation of regional writers and filmmakers to students who had likely never heard of them before.

Columbia University was located in a still-rough corner (back then) of northern Manhattan (see map plot, below) and moving to the school had been a difficult adjustment for me (coming from a relatively small university in rural Ohio). I found the core courses on international relations to be dry and impractical. The classes on political philosophy and history were meatier and more interesting, but I wasn’t as prepared as I should have been and it was always a struggle to keep up.

Ironically, it was only in Professor Sanders’s smallish colloquium – while casually chewing the fat with a dozen or so other grad students about cultures we scarcely knew the first thing about -- where I finally started to feel at home.

I can still see the class in my mind’s eye. We met once a week in the evening in a room that was bigger than what we needed (probably because the class required a space with a film projector). Sanders played the part of the "European dissident in New York" flawlessly. I remember his long, stringy hair, dapper, elbow-patched blazer, and vaguely hard-to-place European accent. He conveyed an obvious love for the subject through his big, infectious smile.

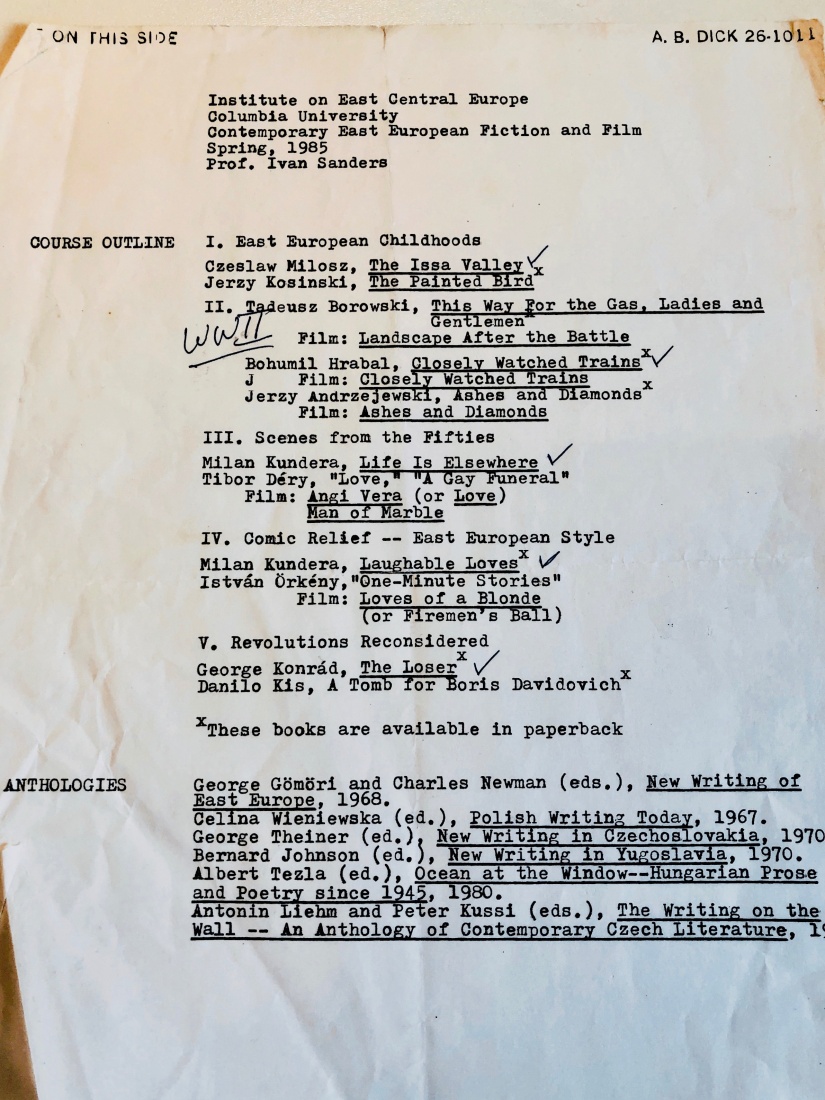

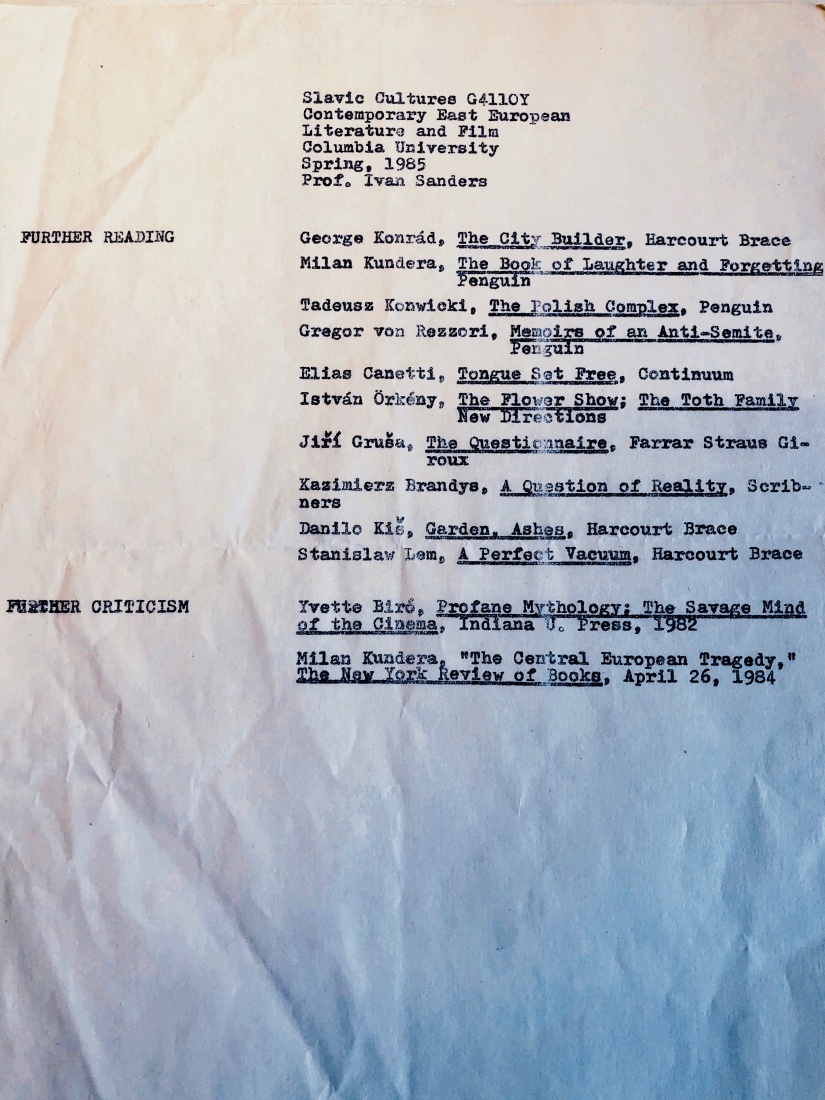

Most importantly, he had impeccable taste when it came to choosing books and films. To refresh my memory for this post, I’ve pulled out our old syllabus and have it in front of me on my kitchen table. Anyone wanting a grounding in pre-1989 Central European literature and film could do worse than simply combing through his recommendations and checking off the titles one-by-one (I’ve posted scans of the syllabus here; double-click on the image to bring up a readable version).

Reading the outline, I see where Sanders cleverly divided the four decades that the course would span (from the end of World War II through the mid-1980s) into five broad historical themes. This allowed him to group together works from all of the different countries and cultures and still have something consequential to say about each. People from outside Central & Eastern Europe often don’t realize how different Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, Romanians and the others really are from each other -- and how challenging it can be to make meaningful generalizations.

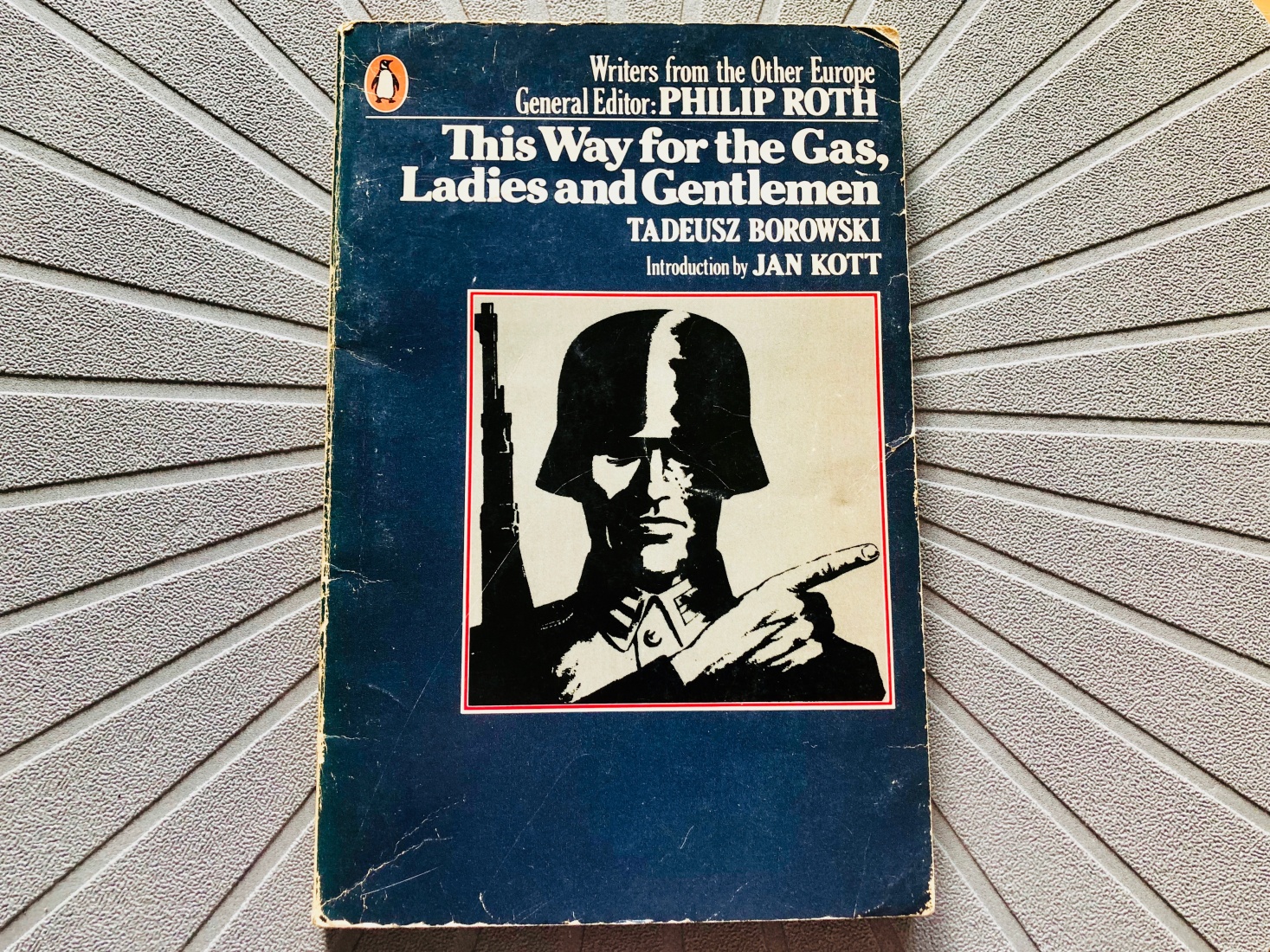

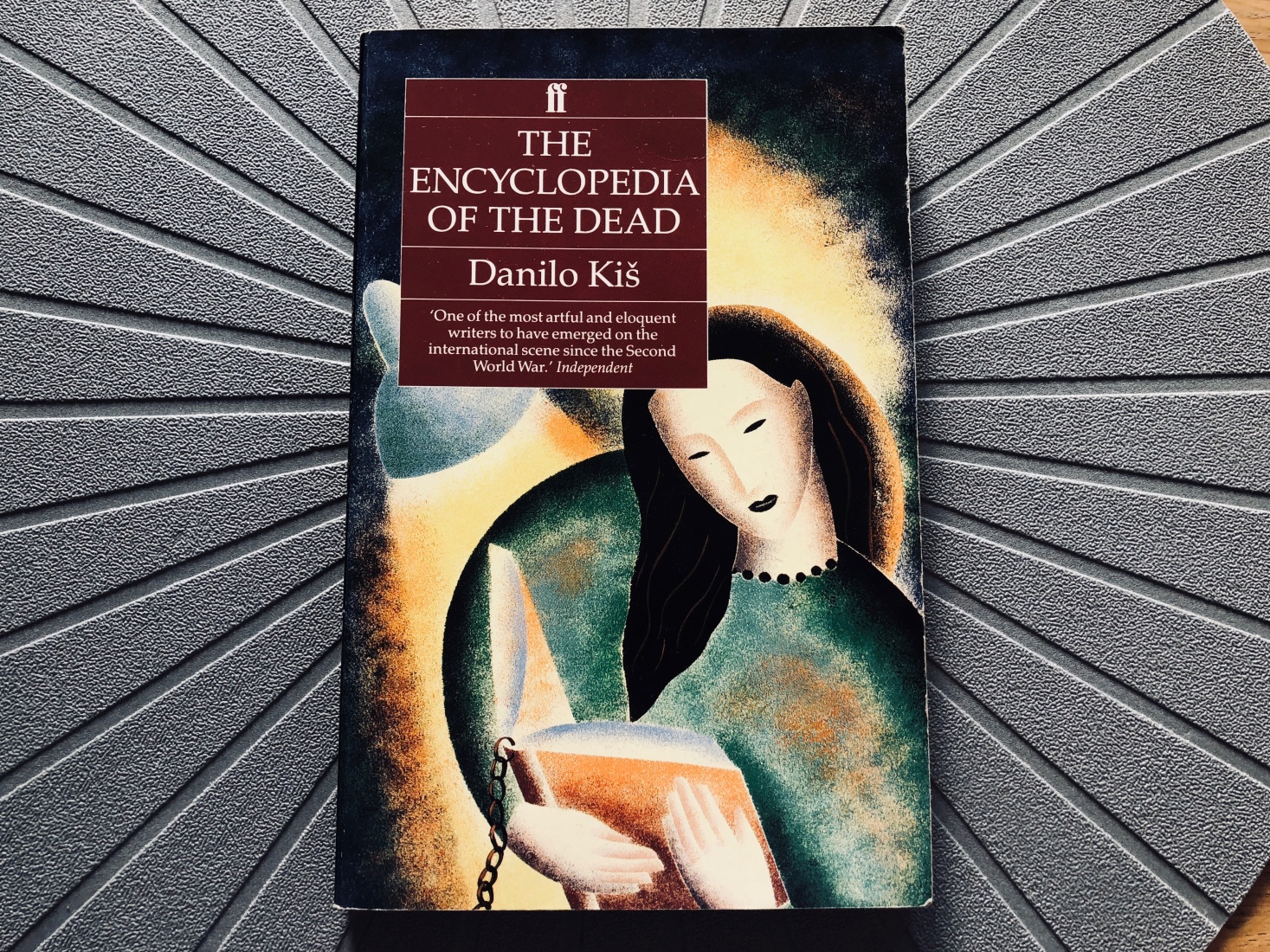

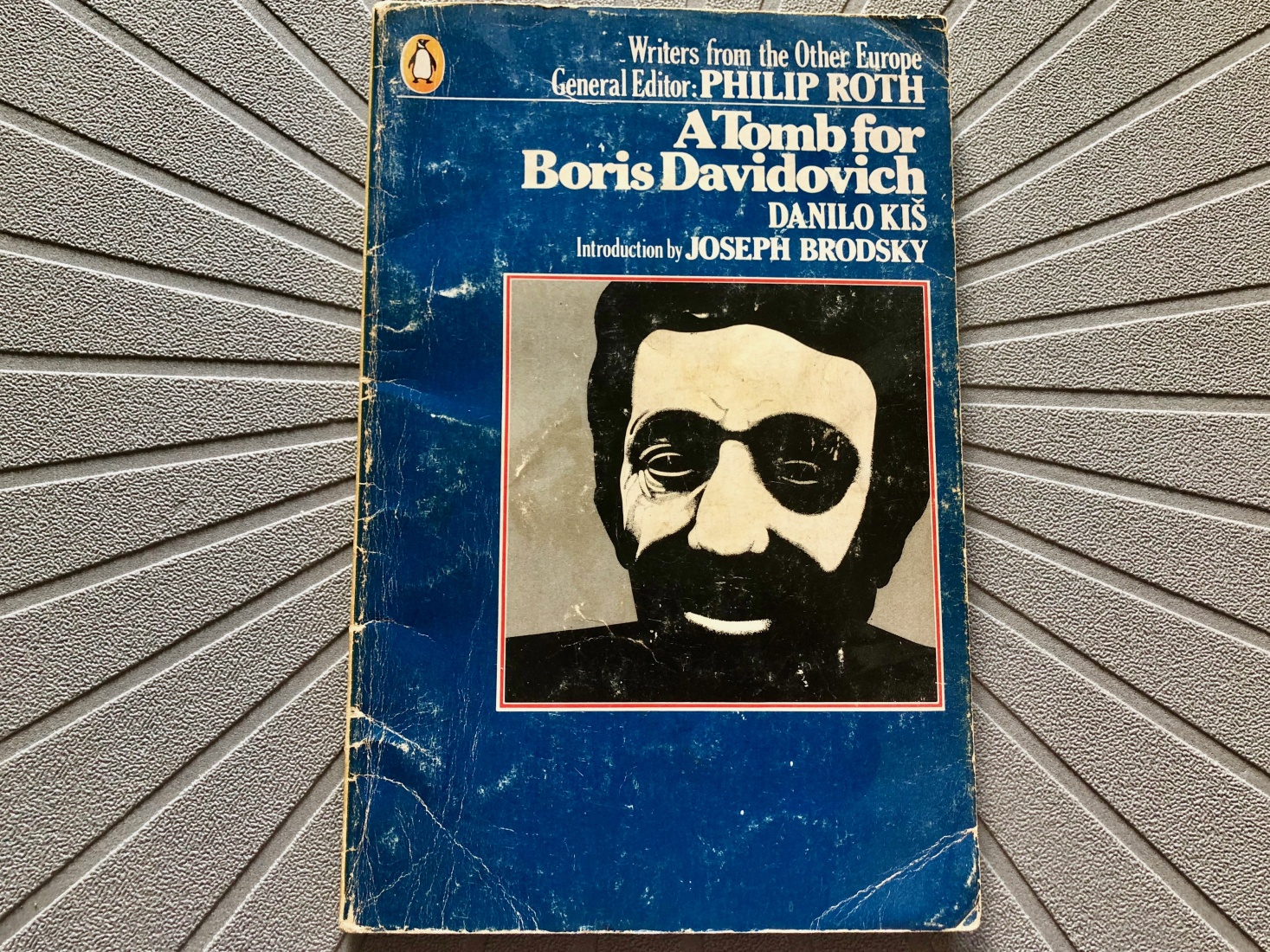

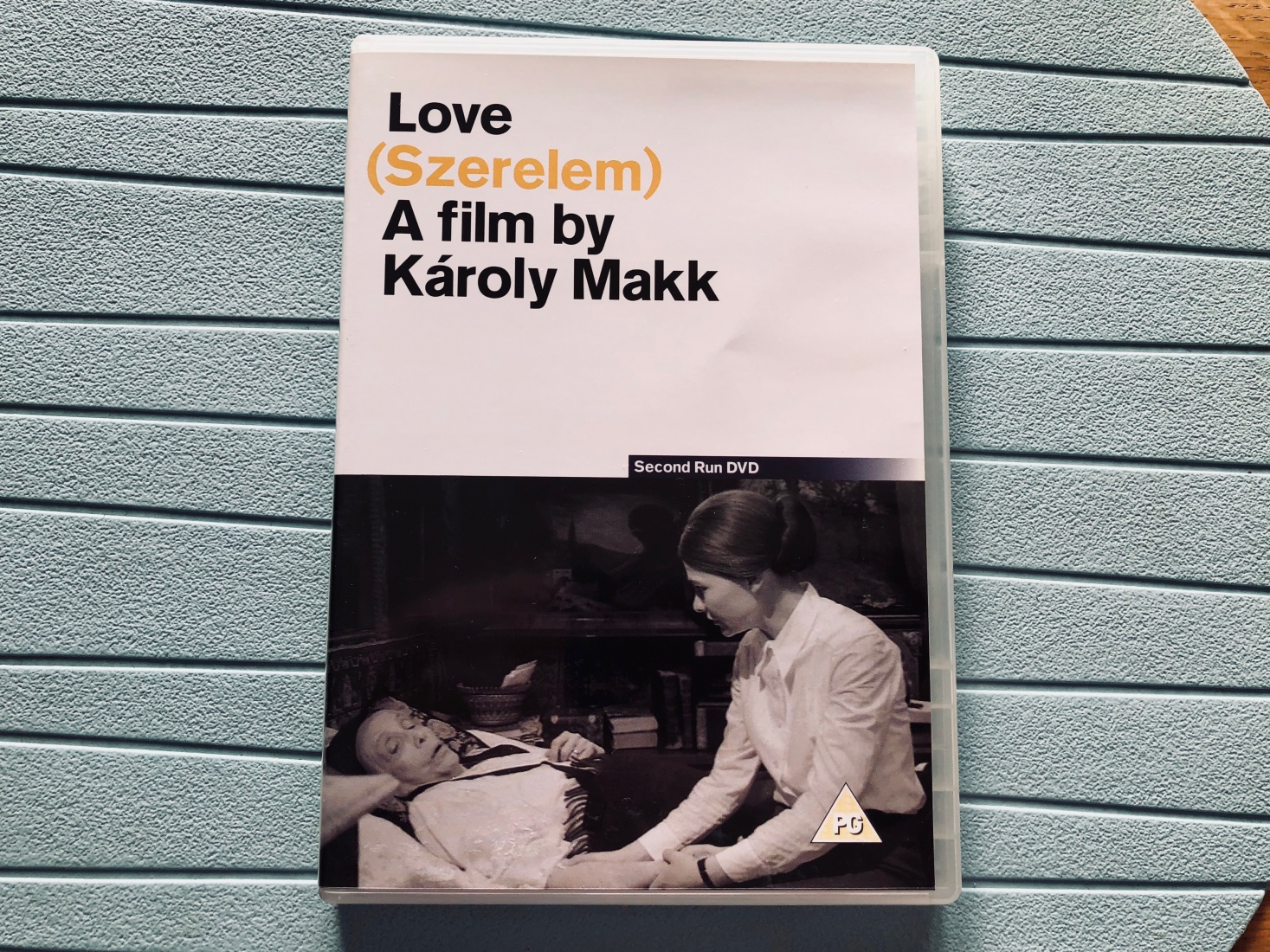

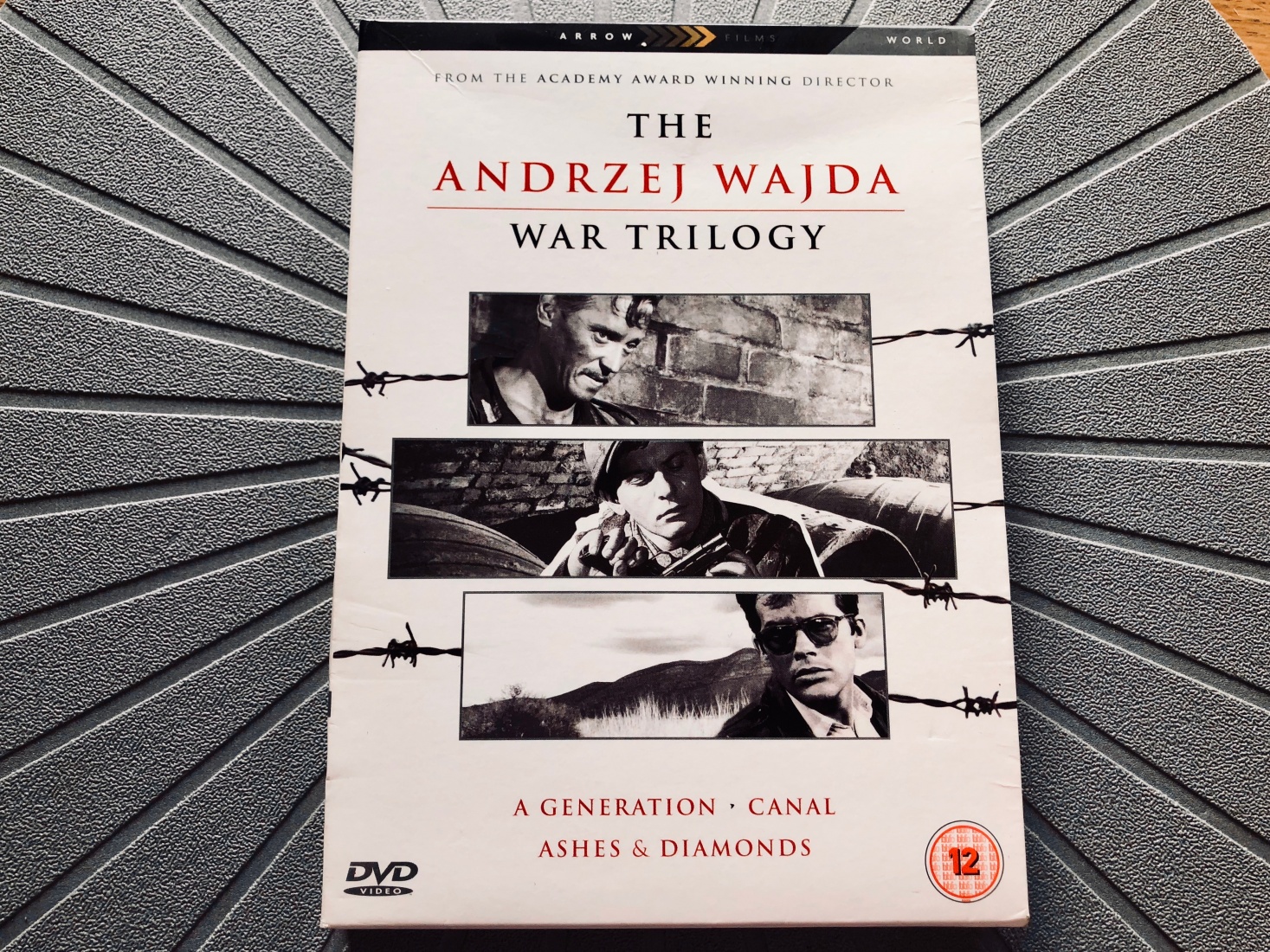

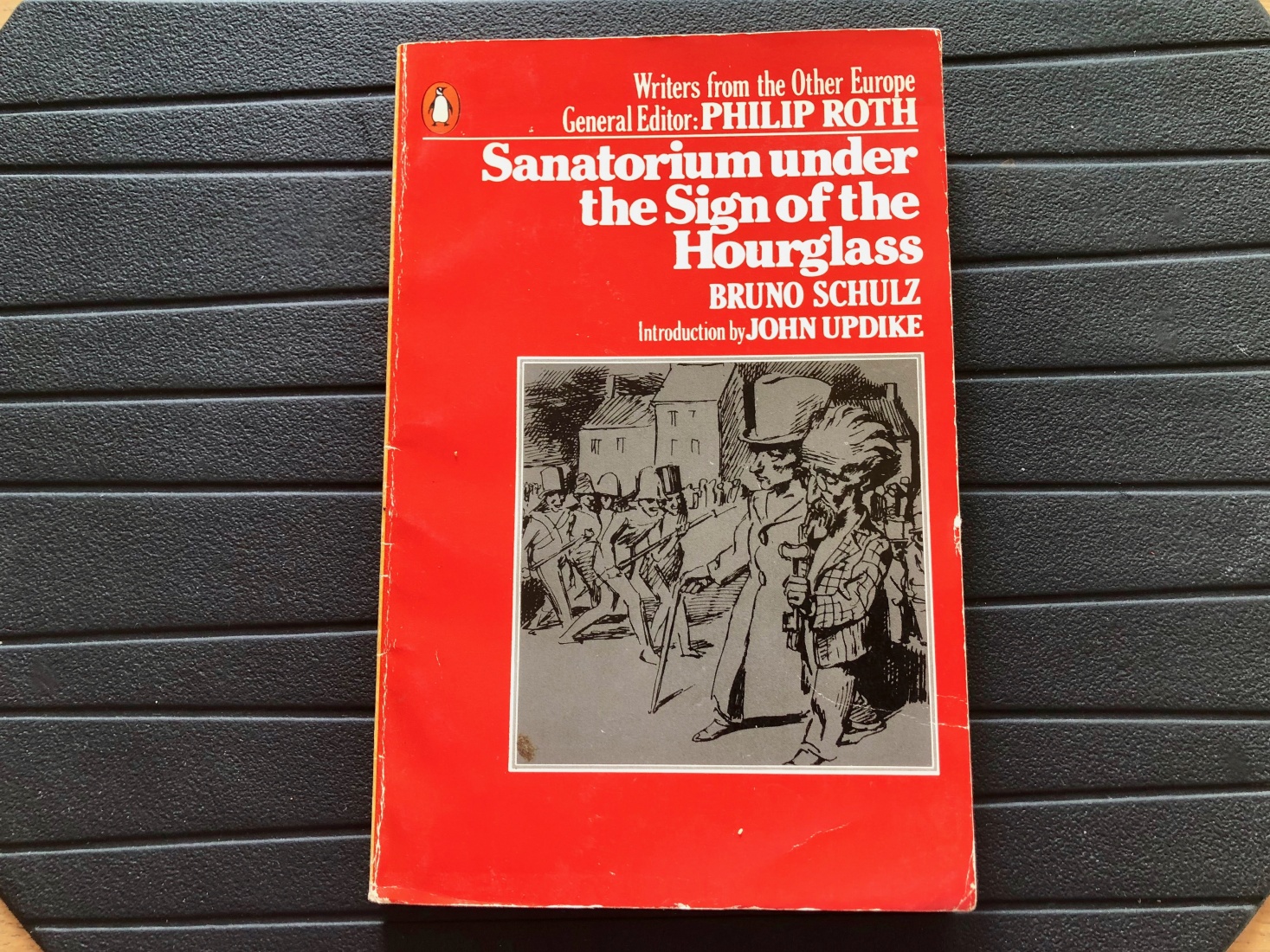

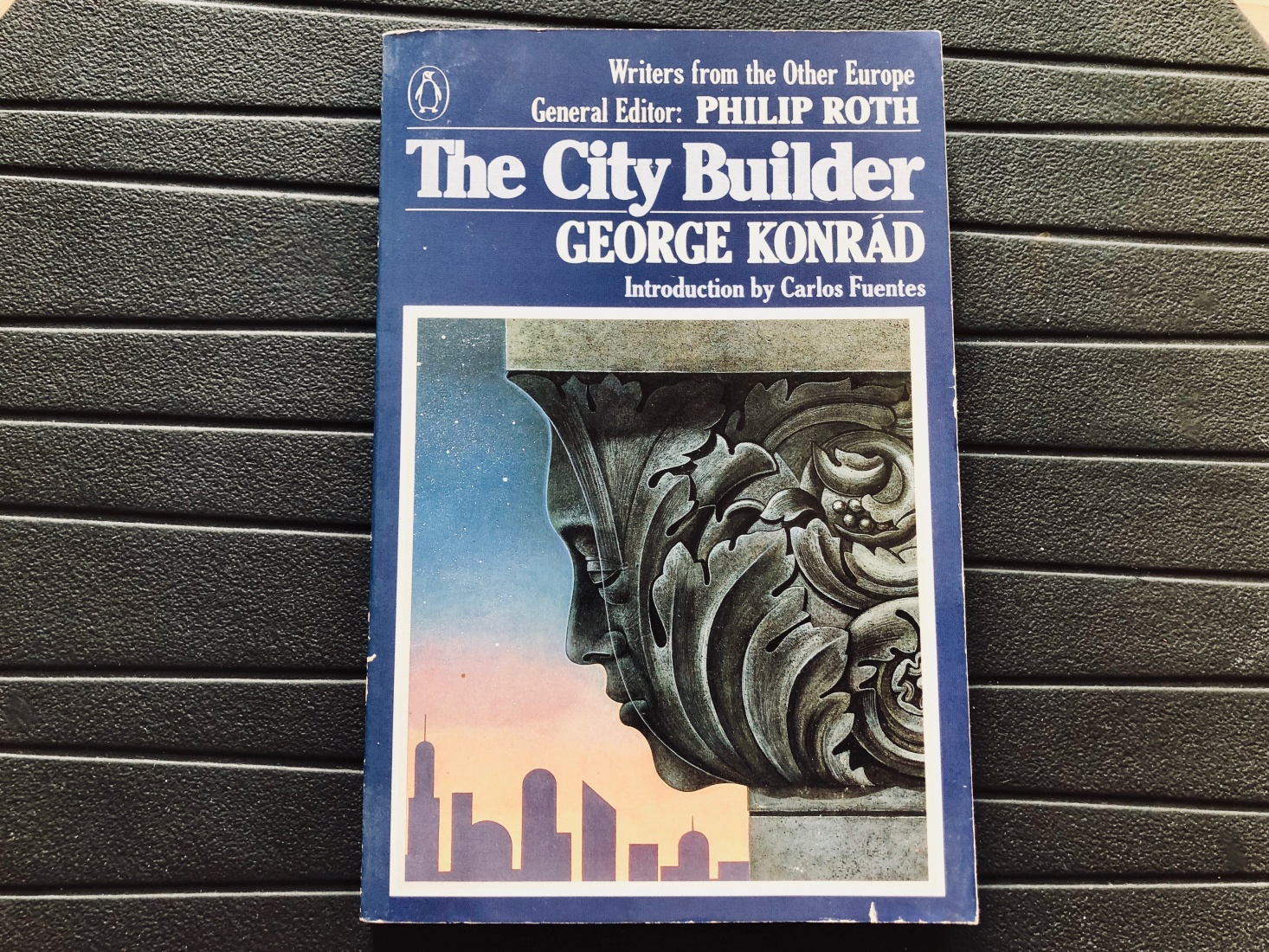

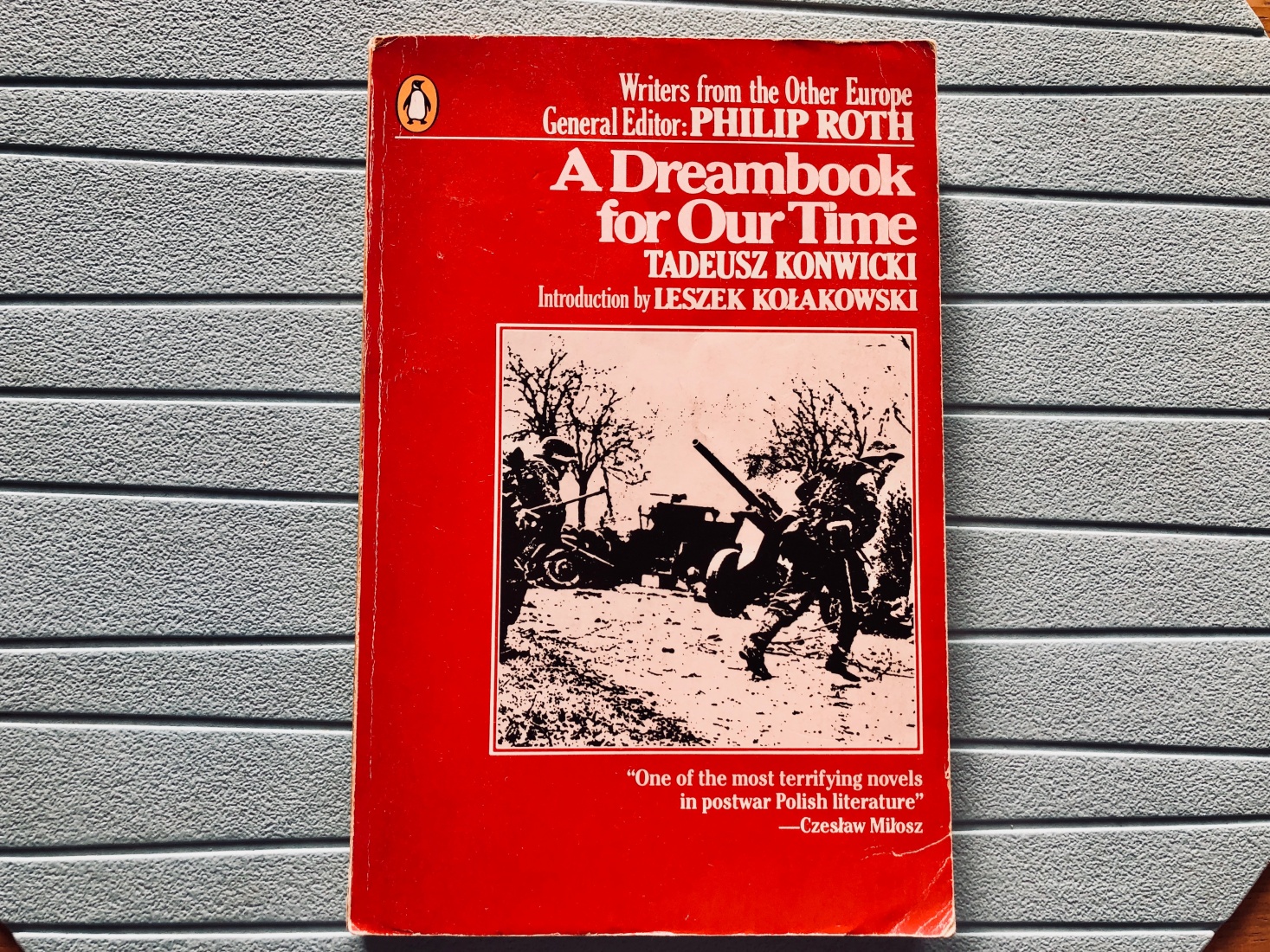

For books, Sanders drew liberally from Penguin USA’s groundbreaking paperback series: "Writers from the Other Europe." Edited by the late American author Philip Roth, the series linked writers as diverse as Czechs Milan Kundera, Ludvík Vaculík and Bohumil Hrabal, Poles Jerzy Andrzejewski, Tadeusz Konwicki, Witold Gombrowicz and Tadeusz Borowski, Hungarian György (George) Konrád, Serbian Danilo Kiš, and several others.

The titles included introductions by the likes of John Updike and Joseph Brodsky which lent the books a literary urgency and highbrow, contemporary allure. I devoured the books at the time, and still have several well-read copies on my bookshelf. Among other things, the series helped forge in my mind an intellectual link between Central Europe and New York -- part fact, part fiction -- that still guides my interests and helps me make sense of my life choices.

It's difficult to pin down what was so interesting about those books and films back then (so many years later and after having spent so much time living in Central Europe).

I could write things like that the books and movies felt relevant and necessary in ways that American and Western culture, at the time, did not. Writers and filmmakers in Eastern Europe worked under constraints -- and had to stake out contorted intellectual positions -- that were unknown or at least unnecessary in the United States. Just the reality of the Cold War made everything from Eastern Europe seem so ridiculously important that reading the books and watching the movies made you feel almost like a player yourself.

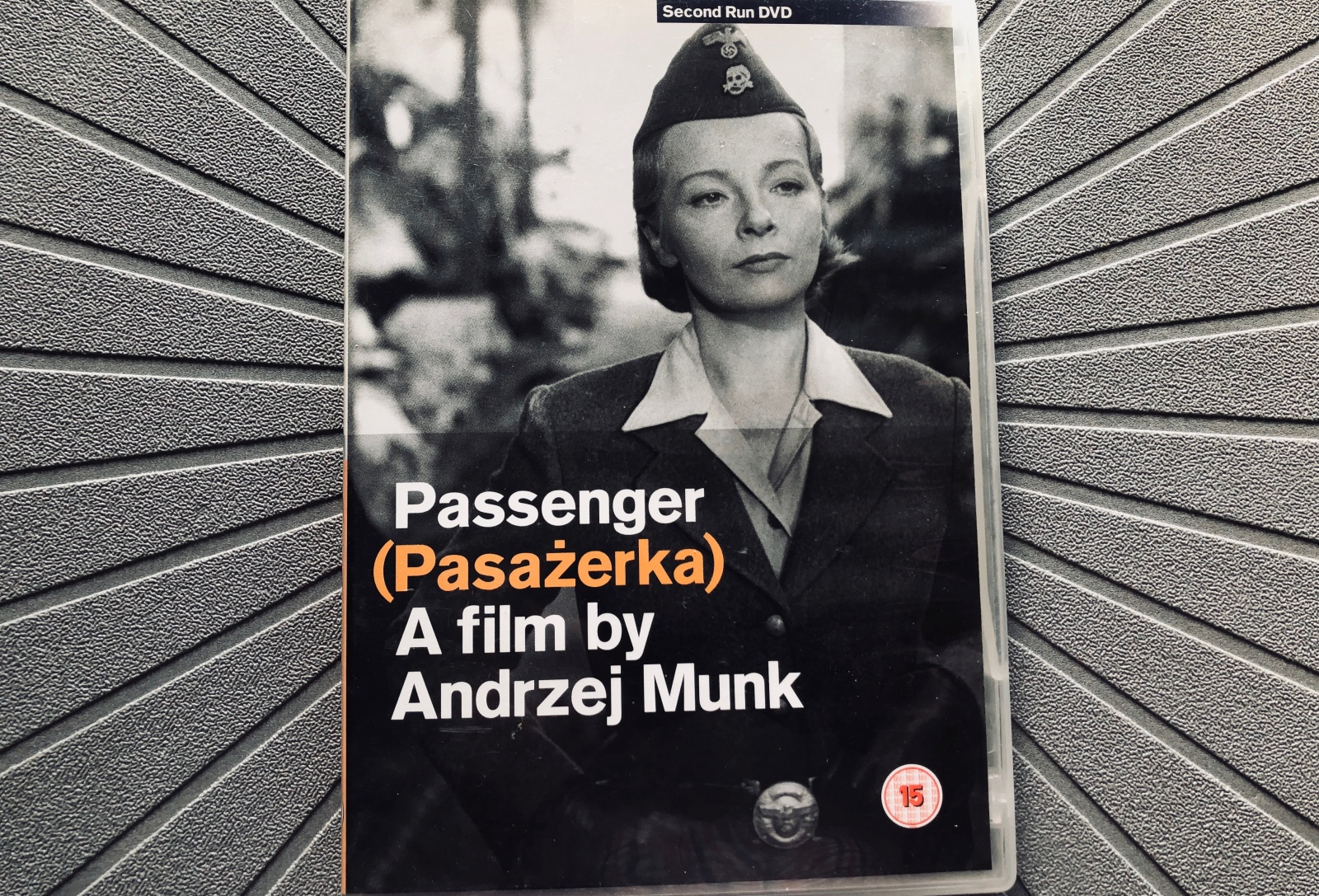

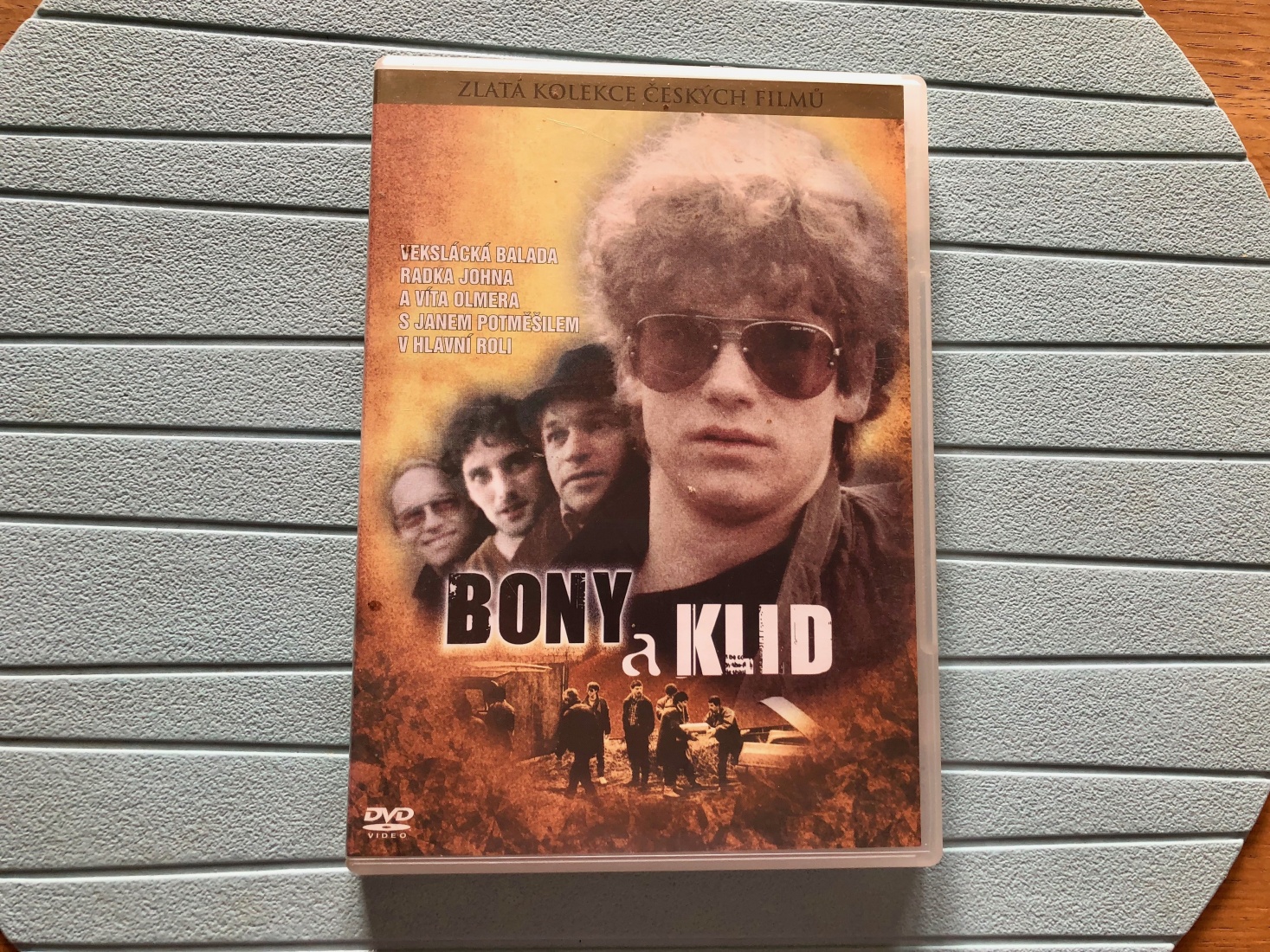

I could write those things and they’d be true, but they’re also a little self-evident and not very personal. Instead, I’ll go through the syllabus and pull out a couple of writers and movies that made the strongest impressions on me at the time. (I’ve used the photos here to discuss books and films I wasn't able to address in the text).

First off, the Sanders class was my first exposure to the writings of Milan Kundera. We read his “Laughable Loves,” “Life is Elsewhere” and, still my favorite, “The Book of Laughter & Forgetting.” It’s hard to imagine now (especially since I now live in the Czech Republic, where Kundera is not particularly admired or highly valued) what a breath of fresh air he seemed to be in the 1980s. His writing cut effortlessly between humor, love, politics and philosophy … and he told entertaining stories in the process.

It’s enough for me to re-read that first passage from “The Book of Laughter & Forgetting” to get those old goose bumps again. That’s the part where Kundera describes a photograph of former Communist leader Klement Gottwald standing on Prague’s Old Town Square to announce the February 1948 coup d’état. During the event, Gottwald is flanked by his deputy, Vlado Clementis, who offers Gottwald a fur hat to keep warm. Four years later, Clementis was charged with treason, hanged and subsequently airbrushed from all official photos. As Kundera writes: “All that remains of Clementis is the cap on Gottwald’s head.”

It’s maybe worth pointing out that Kundera was also the most controversial author we discussed in Sanders’s class. I can still remember the heated debates we had (even back then) over whether his stories were irreparably misogynistic. I’ve always thought that debate misses a bigger point about his work, but I’ll leave that discussion for another day.

The class was also my first brush with the controversial Polish Holocaust-era writer, Tadeusz Borowski. His “This Way for the Gas, Ladies & Gentlemen” is a shocking, insider look at daily life at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where Borowski was a political prisoner and kapo. He was used by the Nazis to collect and sort the belongings of the new arrivals. In Borowski’s telling, the shock for the reader comes not so much from the murders and the gassings, but more from the dreary banality of day-to-day life at the camps. I try to re-read the book once a year and always bring it with me on trips to Auschwitz. Borowski committed suicide by gassing himself to death in 1951.

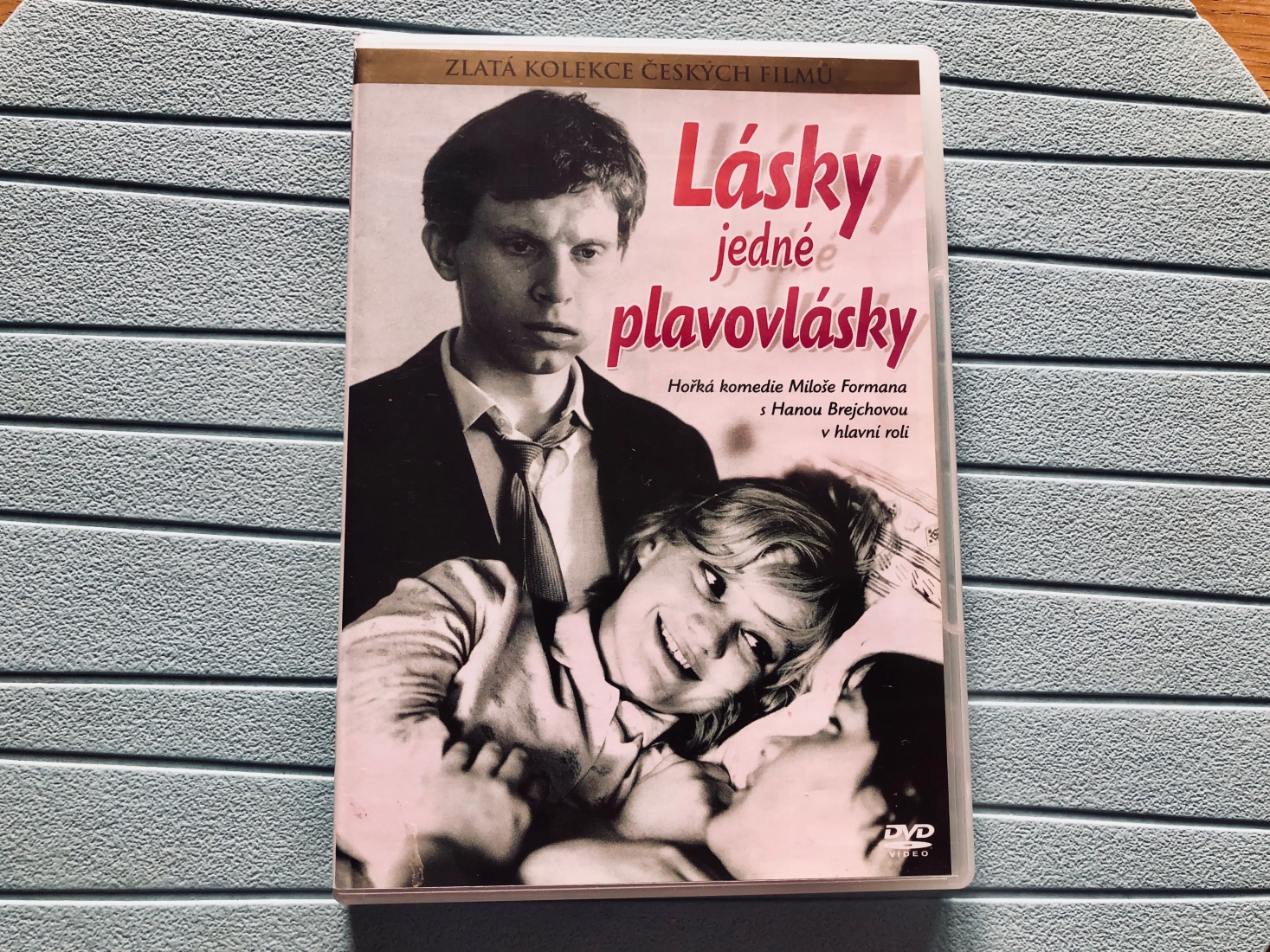

The class also introduced me to two films, both Czech, that remain favorites to this day: Miloš Forman’s “Loves of a Blonde” (Lásky jedné plavovlásky), from 1965, and Jiří Menzel’s “Closely Watched Trains” (Ostře sledované vlaky), from a year later. Both are bittersweet comedies from the Czech “New Wave” of the mid-1960s, when a political thaw briefly allowed some of the country’s best directors to poke the eye of the ruling regime through pathos and humor. Both films hold up to this day. To catch some of the bittersweet flavor of the Forman film, check out this YouTube video of the opening credits.

I finished my degree in 1986 and promptly found work at a small business publication in Vienna, where I could put my hard-earned (and expensive) Cold War political and economic education to work. The irony, though, came just a few years later, in 1989, with the fall of communism. Almost everything I’d studied at Columbia suddenly became obsolete -- everything, perhaps, except for that elective course on Contemporary East European Fiction and Film.

Unlike those dry classes on international relations and the ins and outs of centrally planned economies, our once-a-week colloquium on literature and film afforded cultural and historical insights that remain relevant even now as I go about my day-to-day life in Prague – or travel throughout the region on various writing assignments.

It’s a valid criticism to point out that many of the films and books on our old syllabus no longer accurately describe the region I now live in, and the reputations of some of the directors and authors – including Kundera himself – have declined somewhat over the years. But it’s also true that the realities those works described are somehow baked into the DNA around these parts. I’ve seen firsthand over the years that cultures tend to change a lot more slowly than do political or economic systems.

A few years ago, I tried to repay the favor that Sanders’s course had given me by teaching a variation of that same course to a new generation of students. Prague’s Anglo-American University contacted me about teaching a class on Central European history and left it to me to come up with an approach. I suggested literature and film, and used the Columbia course as a model for my own syllabus.

I pulled out a couple of the Polish authors whom I didn’t feel had aged particularly well, and substituted Kundera’s “The Joke” for the Kundera titles, but otherwise didn’t make too many changes. For the films, I added Romanian director Cristi Mungiu’s disturbing “4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days” and one of my own favorites covering the end of the '80s: the Czech film “Bony a Klid.” With the Czech film, I wanted to show my students how sleazy Prague had become by the end of the communist period.

In general, I was impressed by how well a group of young undergrads – including many American students – responded to the books and movies. Our discussion of the “The Joke,” for example, seemed to be far more incisive than anything we ever did at Columbia in the 1980s.

The only truly uncomfortable moment (for me, at least, as the instructor) came midway through the screening of “Bony a Klid,” when the main characters suddenly strip off their clothing and begin what feels like 45 excruciating minutes of explicit love-making. I had totally forgotten about that scene -- and some of my students were shocked. Say what you will about life under communism – particularly by the late-1980s – but it was certainly not prudish.

Great post, Mark. Are those photographs of your books and DVDs? I too have many of the books you cite but alas not in those funky editions!

Hi Joe, indeed those are my books. Happy to lend one sometime if you’d like. Mark

Great post that brings back a lot of memories for me too, although central European lit was sort of a side street for my primary education in Russian lit. But I took a similar course (without the films) at Grinnell College, and I agree with your observation that it is among the most continually relevant parts of my educational experience to this day. For others interested in this topic, I think it is also worth mentioning the great Slovak (Czechoslovak) film The Shop On Main Street. Stylistically, it is a bit dated, but thematically, it could not be more important. I often wish someone would do a remake.

I really enjoyed reading this. I started studying Czech in 1997, went to Prague for the first time in 1998 and studied Czech lit & culture at Charles University and the University of Toronto. I intended to pursue more post-graduate studies on East-Central Europe but drifted away from the field about 10 years ago, though the books I studied then (and continue to read) still definitely impact the way I see the world. This post brought back a lot of that initial fascination that first drew me to the region. I’m definitely going to be exploring some of those films & books from the syllabus. Thanks for sharing it!