I love public transportation, but I’m more of a tram than a metro guy – at least where Prague is concerned. I even wrote a love letter of sorts to Prague’s trams, an ode to those "whales on rails," a few years ago: Riding the Rails of Prague.

My preference for trams in Prague has to do with the fact that the customs and habits you see on trams here reflect more the city's own traditions, and not simply a mode of transportation. Prague’s metro culture, by contrast, feels not unlike that of any other large city with a subway system anywhere in the world.

The little niceties of daily life you still find on Prague’s trams – like when a man gallantly springs to his feet to offer his seat to an older woman – are only halfheartedly enforced on the metro. It feels more like a jungle below ground. The main metro mores here include informal rules like “don’t make eye contact with strangers,” “don’t talk too much,” “don’t stand in front of the car door when people are getting on and off,” and, whatever you do, “don’t block the escalators.” Prague is definitely a “stand to the right, walk to the left” type of city.

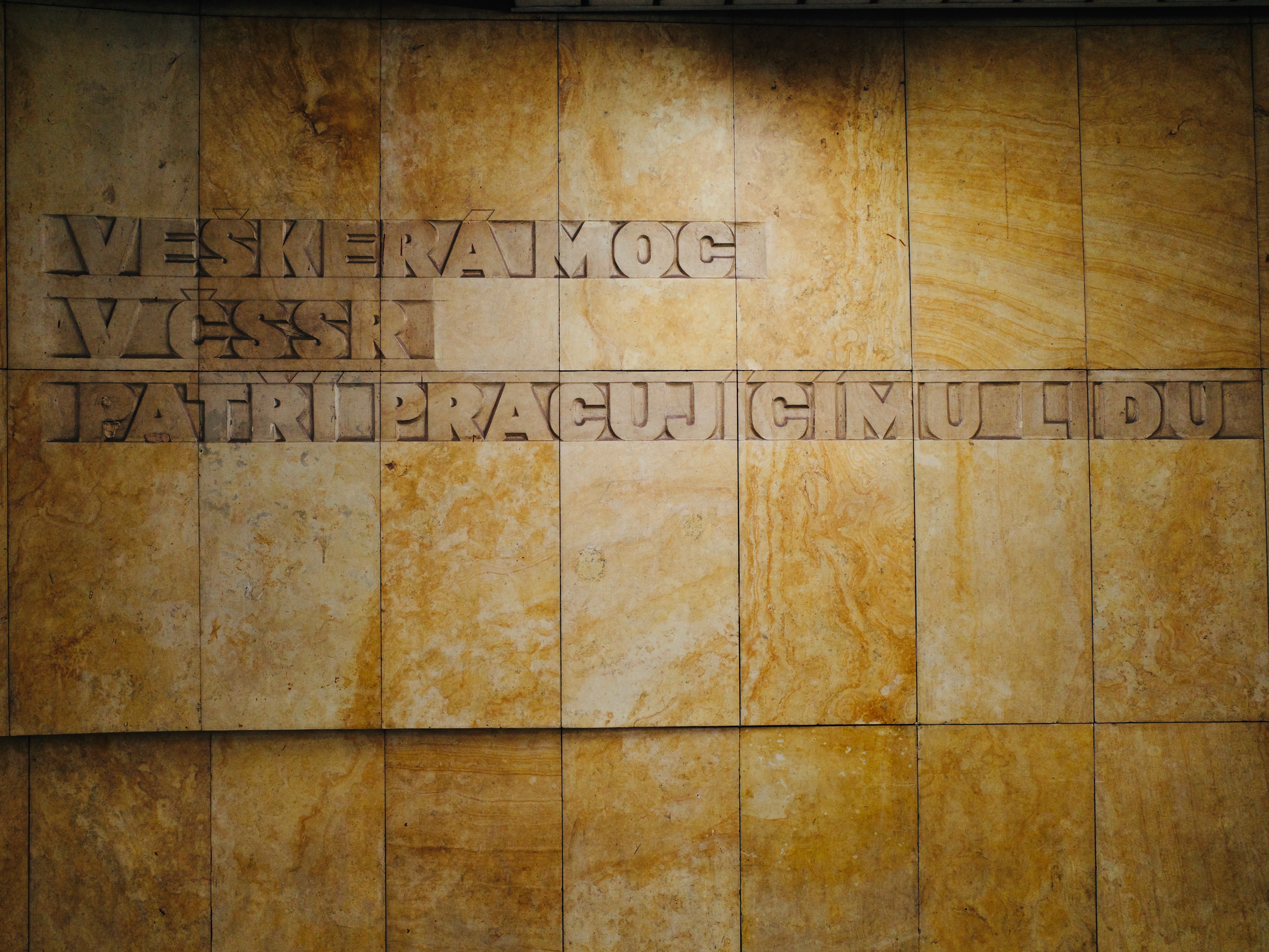

Still, there are enough quirky aspects to Prague’s metro system to make for a fascinating study. The stations and lines were largely planned and built in the 1970s and ‘80s by the former communist regime. If you know where to look and what to look for, the stations remain a repository of history from a time when, in name at least, all was done for the glory of the working class. Prague still lacks a decent museum of communism (the privately run one we have now doesn’t really count). If you’d like a taste of life back then, you could do far worse than buy a metro ticket and spend an hour or so rocketing around underground.

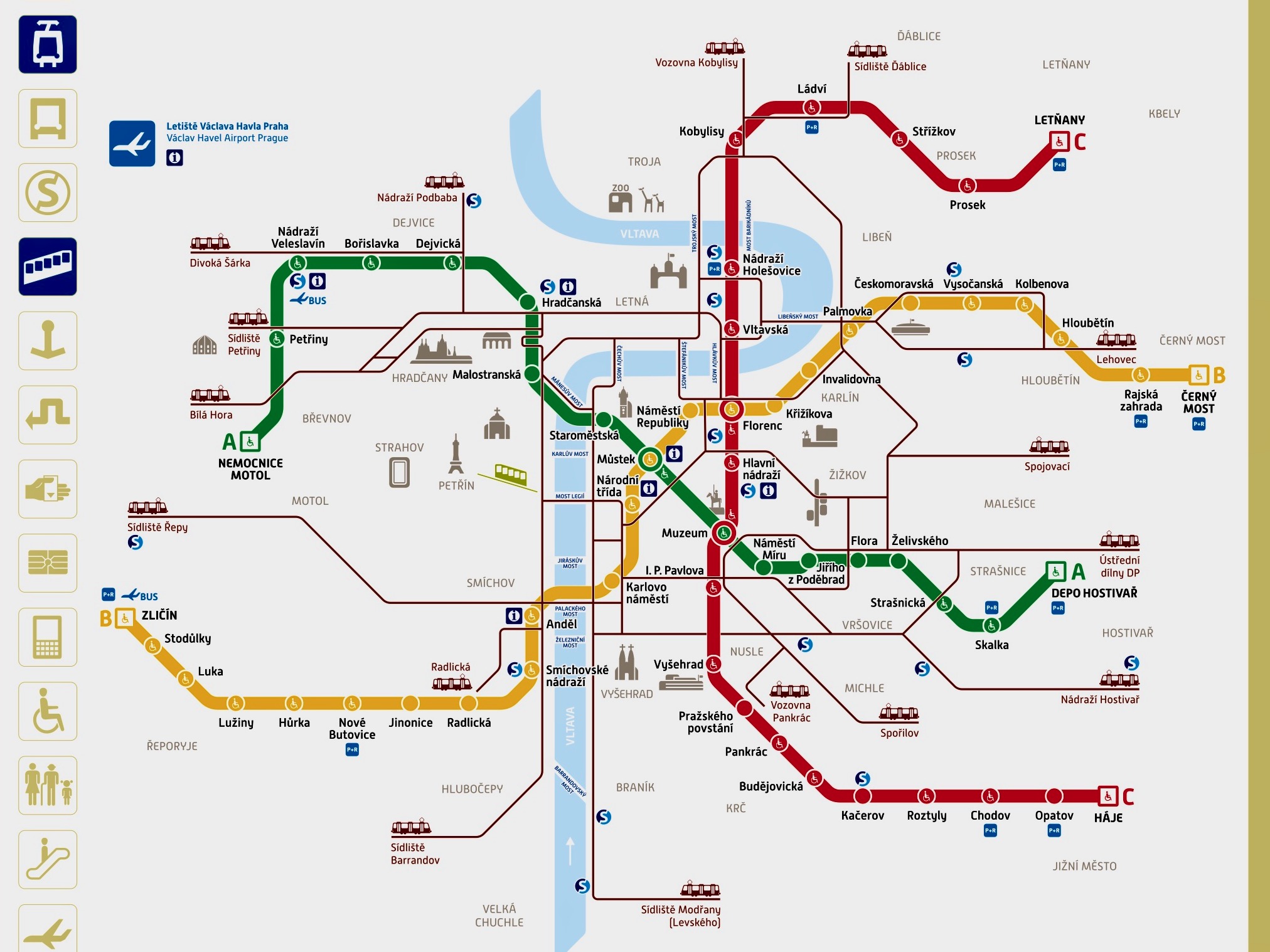

Prague’s metro is relatively small by world standards. The system has just three lines (see the map above). The lines are distinguished by both letter and color, and the order goes like this: Line A (green), Line B (yellow) and Line C (red). There’s no central station, where all three lines meet up. Instead, three different stations (Muzeum, Můstek and Florenc) serve as connecting nodes, where two lines cross. It’s very efficient and you can quickly cover a lot of ground.

Confusingly, the letters don’t correspond to the ages of the lines. The system was built piecemeal, starting in the early 1970s, with parts of Line C being the first to go into service, in 1974. A few years later, the central stations of Line A were commissioned, followed a few years after that, in the mid-1980s, with parts of Line B.

The system has inched outward every half-decade or so since those early days, with the opening of several new stations. The last big extension came in 2015, when Line A was prolonged westward from Dejvická to its new terminus at Nemocnice Motol.

As a short aside, this most-recent build-out had a (temporarily) grievous effect on me as a travel writer (and on every other travel scribe writing about Prague). The extension moved the main arrival point to the city for visitors using the airport bus from the Dejvická metro station (where it had been for years) to a new station, Nádraží Veleslavín. Dozens of guidebooks were forced to rewrite their Prague transport chapters or risk being out of date.

The three lines have different letters and colors, but more curiously, they also have three distinctly different personalities.

Line A might be termed the grandest (or even haughtiest) of the three. It connects the city’s main medieval attractions, including ancient Prague Castle (metro: Hradčanská), the Lesser Town (Malostranská), Old Town (Staroměstská), and Wenceslas Square (Muzeum). The names of the stations along this line don’t flirt much with excess or propaganda, but rather stick close to historic or geographic reality. A couple of stations even play on Bohemia’s long, rich tradition of religious reform. King George of Poděbrady, the 15th-century Hussite king, is honored at metro station Jiřího z Poděbrad, and Hussite preacher Jan Želivský is remembered by the station Želivského.

The stations along Line A also feature some serious international design cred, including those colorful, Pop-Art-like aluminum tiles (part concave, part convex) that line the underground walls and appear in so many Instagram posts on Prague. These were the inspired work of designer Jaroslav Otruba. Line A is also the deepest of the three lines, and many stations show off impressively long escalators. The station at Náměstí Míru even boasts the longest escalator in the European Union, a whopping 87 meters (285 feet), and has become a tourist attraction in its own right.

Line C, by contrast, is a kind of historical upstart, the radical or the rebel. It’s traditionally regarded as the “communist” line (which might explain the letter “C,” or that red color). Line C was built largely to connect the center of Prague with the sprawling worker-housing projects on the city’s southern edge that, back in the '70s and '80s, were the pride and joy of communist central planners.

The stations along Line C, with a few exceptions like Vyšehrad (the former “Gottwaldova” station), are fairly ho-hum from a design standpoint; their respective glories are reflected instead in the lofty names that the communists originally gave them to promote their ideology (alas, most of the stations were renamed in 1990).

To give you a flavor, the metro stop at today’s Holešovice station was once called “Fučíkova,” after the communist-journalist Julius Fučík, who was persecuted by the Nazis. The name “Gottwaldova” referred to Klement Gottwald, the country’s early communist leader, who assumed power in the coup of 1948. Today’s Pankrác station was simply called “Youth” (to glorify youth, I guess); Opatov station was named “Friendship.” Some of my personal favorites include Chodov, once known as “Builders” (a tribute to those building the metro), and modern-day Háje, which was originally named “Cosmonauts” to honor the Russian space program.

Line B is harder to pigeonhole. It’s the system’s middle child: confused and neglected: neither the grander A line nor the radical C line. I can't help but think as I write this (and please pardon the American cultural reference) of the classic 1970s' TV sitcom “The Brady Bunch.” In one episode, Jan, the aggrieved middle daughter of three girls, goes on an epic rant: "It's always Marcia, Marcia, Marcia!" she cries, referring to her always-perfect, older sister Marcia. Maybe the "B" in the metro line's name stands for "Brady"?

There are a couple standout stations along Line B, such as Anděl, formerly called “Moskevská” to honor the city of Moscow. Most of the line, though, is fairly forgettable. I challenge anyone to list off the Line B stations from Smíchov, heading west, to its terminus at Zličín in the correct order (and without looking at a map). It can’t be done.

To make matters worse, the stations along Line B seem prone to a degree of blight that doesn’t afflict the other lines so severely. This is a purely subjective take, but stations like Anděl, Karlovo náměstí, Florenc, Invalidovna, Palmovka and others along Line B are some of the seediest in the system. Even central Národní třída station (National Avenue), which you’d think from the location would be pretty swanky, was awfully dank before they renovated it a few years back.

My first impression of the Prague metro, from visiting way back in 1984, was that it was a little cold. I’m not talking here about the physical temperature – though the deepest stations along Line A can remain chilly even in mid-summer – but rather the overall impersonal vibe of the place. Maybe it was my frame of mind back then. If you’ve read my blog post “The Case of the Missing Roommate,” you’ll remember that’s the trip I took here with my college roommate, Matt, and the two of us got separated in a comical, communist-era series of crossed wires. For three days, I had no idea what had happened to him, and I traveled up and down the metro lines hoping I’d catch a glimpse of him somewhere.

Back then, I was living in New York and my only point of reference for an underground transportation system was NYC’s shabby subway. By contrast, Prague’s metro was incredibly fast, reliable and clean, but it also felt a little depersonalized and robotic.

By way of an example, I remember a hot summer day in New York sometime in the mid-‘80s. My girlfriend Delia and I had hopped the subway for a trip out to the beach at Far Rockaway in Queens. At each station, the conductor would call out over the loudspeaker in that signature NYC subway sing-song: “All aboard! Watch the c-l-o-s-i-n-g doors! We’re heading for the beach!” It felt like a party train. The trip seemed to take hours as passengers would stick out their arms and legs at each station in order to block the doors -- for no reason other than just because they could.

In Prague, one of the first things I noticed was that there were no train conductors, as such. As the train would prepare to leave each station, instead of a human voice telling passengers to “watch the closing doors,” we would hear a rather stern-sounding recorded warning in Czech: “Ukončete výstup a nástup, dveře se zavírají” (Stop leaving and entering, the doors are closing).” I couldn’t understand a word at the time, but it sounded pretty harsh. The doors would then slam (and I mean slam) shut. No one dared stick out an arm or leg just for fun as they’d be unceremoniously dragged to the next station.

Since the 1989 Velvet Revolution, it should be mentioned, the Prague metro has become far more forgiving. They still play that same recorded message (click here to listen to an audio clip), but they’ve since added the word “please” (prosím) to the mix, as in “Please stop leaving and entering …” The voices now include women, and not just men. The doors have been rejiggered to be far gentler if they happen to close in on a late-boarding or -leaving passenger. No one’s going to lose a limb.

Over the years of living in Prague, I’ve warmed substantially to the metro and have grown to admire its speed and efficiency. I’ve even adopted several stations as my “home” station, depending on where I was living or working at the time.

My first apartment in Prague, in April 1991, was located directly above Staroměstská, and I quickly became acquainted, by sight, with the clerks working the station’s kiosks and the cast of characters who'd linger, day and night, at the entrances and exits. Some of those guys are still hanging around.

I later moved out to what was still a raggedy-looking Jiřího z Poděbrad station in Vinohrady. This was years before the neighborhood would gentrify into the café-lined, upscale quarter that expats lovingly refer to as “JZP” today.

In the early days of opening the Globe Bookstore & Coffeehouse, in the mid-‘90s, futuristic Vltavská station, on Line C, became my regular. After that, when I worked at Radio Free Europe, I got to know every corner of Muzeum station, near to where the radio had its offices. These days, my “home” station is Hradčanská, on Line A.

Anyone who’s ever lived in the same city long enough knows the power of these types of daily associations. Prague has evolved rapidly over the past three decades and even become unrecognizable in places. Thankfully, the metro stations have not changed all that much. For me, they still serve as handy points of reference, and not just to help me negotiate the city’s geography, but to remember its history -- and mine -- over the years.

(For more on the history and art of the Prague metro, see the website Metro Art. Author John Bills uses the metro stations as starting points for a history of Prague in his book, "Via The Left Bank of the '90s." Please feel free to post your own photos of the Prague metro to Twitter and don't forget to tag the pics #RetroMetro.)

Thank you Mark, I appreciated this trip in the Prague metro, awesome pictures- with some nostalgia and most importantly I also learned a lot things ! Great !

Coincidentally today was the first time I took it to go to work (to my new job) in 8 years !

Hi Anthony, Thanks for stopping by and I’m happy you liked the story! Mark

Hi Mark…brought so many memories of my life in Prague…thanks for the story and the photographs are really great.

Hi Homero, happy you liked the story and hope you are doing well. Mark

Brilliant article as always, only complaint is that it is too short!

My home station has always been Cerny Most on the “Brady line”, surely a competitor for the most badly designed and neglected on the network?

Hi Mark, you did lovely pictures or Metro station as kid passing by i never noticed slulptures and unique architecture. Do you have any pictures of exterior or Vltavska stations from early 90’s with 1st graffiti and tags appearing there, i’m looking for photos of this period also from other stations for example Narodni Trida.

thank you

Hi Jan, Thank you so much. I will look around for Vltavska ’90s photos, but I don’t think I have anything like that. Maybe something from a little later, like the early 2000s? Mark

Very enjoyable, thanks for your reflections, Mark. I would disagree with one point, though. Regarding the categorization of the three lines, I always point out to my American students of Czech politics that they can tell the era in which the stations were designed: the C line, in my view, is actually the least “communist” of all – it is the most practical, easy to use (shallowest and most accessible) line of all, showing I would say the practical side of the mid to late 1960s in which it was designed. The political detente of the era being materialized in it, and the sternness of the architecture I would suggest is actually just a facet of the practical neo-functionalism of that time. It was certainly (re-)politicized by 1974 when it opened and neo-stalinist “normalization” was around, yes. During that period, lines A and B were designed, showing much more the dual-purpose nature of the heavy Soviet type of metro lines, running deep and serving as nuclear shelters during the paranoid Brezhnev era. (With line A showing the still-ambitious first stage of the normalization period of the early to mid 1970s, line B with its much cheaper materials demonstrating the increasingly exhausted regime of the late 1970s to mid 1980s.) Overall, a very lovely tribute to the bizarre triangle of the Prague metro, thanks!

Thank you! Yes, good point about Line C and one I hadn’t considered. Truth be told, I sometimes avoid the metro — Lines A or B — because of the super long escalator ride. Line C is actually much more practical. Thanks for reading and leaving a comment! Mark