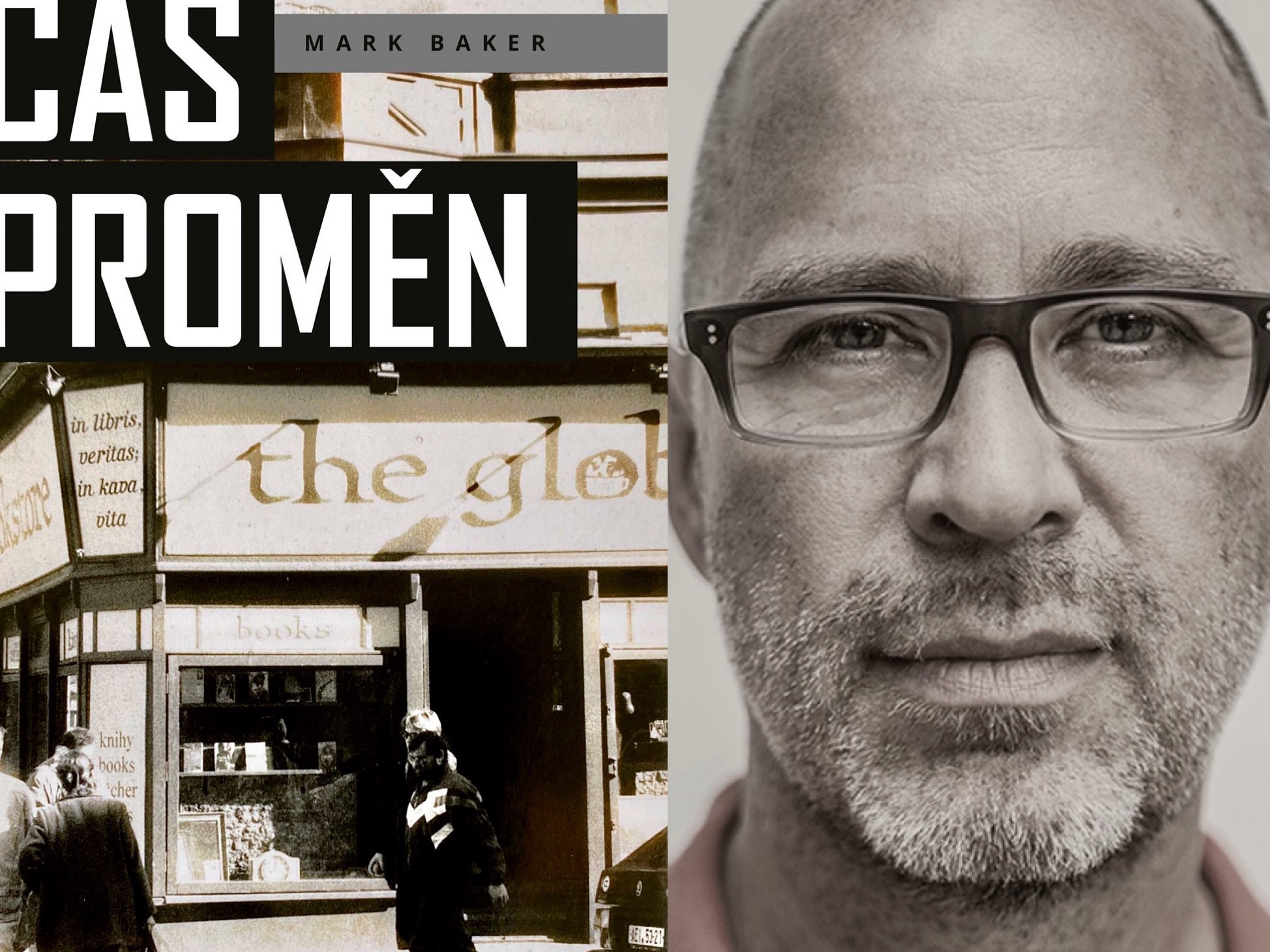

First, a bit of personal good news. “Čas proměn” has now been out in bookstores for around six months and appears to being doing well. My editor at Albatros Media, Jan Dvořák, recently told me he was pleased with the sales figures and that the book got a nice boost over the Christmas book-buying holiday. That boost was likely due in part to a social-media marketing campaign carried out by Seicho Media here in Prague. One aspect of that campaign was to create a new book "landing page" on this blog, which I think helped out a lot.

To be sure, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are relatively small markets, and the monthly figures are still only in the hundreds of books sold, but I’m satisfied with the roll-out and hope the title continues to attract new readers through word of mouth and the media. It’s still a rush for me to walk into a random Prague bookstore and find my book on the shelves somewhere or, better yet, in a stack on a well-positioned table. I don’t think that will ever get old.

Toward the end of last year, I published a post here summarizing the media attention that Čas proměn received in the first few months after its launch. That initial wave included two high-profile reports on Czech TV, as well as reviews in national publications like “Reflex” and “Týdeník FORUM.” After I published that post, thankfully, several other media outlets made space for the book. In November, I did a long television interview with Jaroslav Plesl, the editor-in-chief of the daily "MF DNES," for the iDnes television program, “Rozstřel.” That interview – happily for me -- was broadcast on November 17, a public holiday that marks the anniversary of the 1989 Velvet Revolution. Around the same time, editor Elizabeth Zahradnicek-Haas at the website “Expats.cz” printed a comprehensive interview in English that, I think, really got to the heart of the book. In the November 2021 edition of the Czech edition of “Marianne” magazine, editor-in-chief Monika Mudranincová named my book as one of her personal favorites.

In November, Čas proměn also finally caught the attention of a respected, mainstream Slovak reviewer: the author and journalist Róbert Kotian. Writing in the cultural journal “Kultúrny život,” Kotian took me to task (mildly) for not having quite fully grasped the aspirations of many Slovaks in the early-90s in wanting to form their own state, but he appeared genuinely to enjoy the book and recommended it to his audience. I was grateful for any exposure in Slovakia, where (like here in the Czech Republic) the book is widely available in bookstores but until now hasn't gotten a lot of publicity.

Looking ahead to 2022, it’s natural to assume that much if not all of this media attention will soon dry up (though my editor assures me the marketing lifespan of a book can last as long as two years, so who knows?) Even so, there are a couple articles still in the pipeline, including an interview with Jennifer Walker, the editor at Panel Magazine, a cultural monthly on Central and Eastern Europe. I also hope, finally, to host a long-delayed public reading at the respected bookstore, Reynkovo knihkupectví, in the city of Česká Lípa. Fingers crossed on that one.

Meantime, I’m making slow progress toward publishing an English-language version of Čas proměn, possibly as soon as later this year. I wrote the original text in English, which was subsequently translated into Czech, so the problem isn’t so much producing an English version from scratch, but rather adapting the existing text to make it more relevant to English-language readers.

I’ve since had the English text thoroughly proofread and copy-edited, and even sent off samples to editors and writing coaches at several publishers and organizations. The feedback, so far, has been mainly positive. I’m hoping to avoid having to make too many thorough-going, structural revisions to any new English version. It’s not that I wouldn’t want to or think the book wouldn’t benefit from it, but I’m just not sure I still have the energy for it. My tentative plan for the first quarter of the year is to make some relatively modest changes to the text -- adapting the book’s introduction and adding a new chapter on life in Vienna in the mid-1980s – and see where it goes from there.

I alluded in the intro above to some strange and surprising facts that I’ve learned since publishing the book, and this new information will require at least some re-writing of the original manuscript. I’m still processing the materials and not yet ready to share them fully, but I’ll give you a taste of what I’m talking about here.

As I was conducting the original research for Čas proměn in 2020, I was naturally curious as to whether the Czechoslovak secret police had ever kept a surveillance file on my activities in the 1980s. After all, for several years that decade, I traveled to Czechoslovakia as a Western journalist and even worked with a local translator/fixer, Arnold, who I learned years later had been an active informant for the Czechoslovak security service, the StB. It wouldn't be much of a stretch to assume that I too would have some presence in the official archives. I was surprised (and even mildly disappointed), though, when after requesting to see my file, I was told I didn’t have one. The explanation at the time was that Arnold had enjoyed protection at high levels and that much of the material on him had been destroyed in the period immediately after 1989. Anything with my name on it would likely have been shredded along with it.

Fast forward to the Christmas holidays a month or so ago. Out of the blue, I received an email from Dr. Prokop Tomek, a researcher at the Prague Institute of Military History (Vojenský historický ústav Praha). Dr. Tomek was writing to tell me that he had just finished my book and liked it (which made my day), but then added that I might want to make some changes if I ever decided to issue a second edition. He said that after reading Čas proměn, and particularly the parts about my adventures in Prague in the '80s, he thought it would have been unusual if there had been no mention at all of my name in the files, so he decided to search the archives on my behalf. Much to my surprise, it turns out that I actually did have a surveillance file. Apparently, according to Dr. Tomek, new materials in the archives are coming to light all the time. It’s not a particularly large file (most of it appears to have been destroyed), but the surviving materials certainly provide an interesting (and somewhat unsettling) window into how the security services operated back then (and in ways I had no idea about at the time).

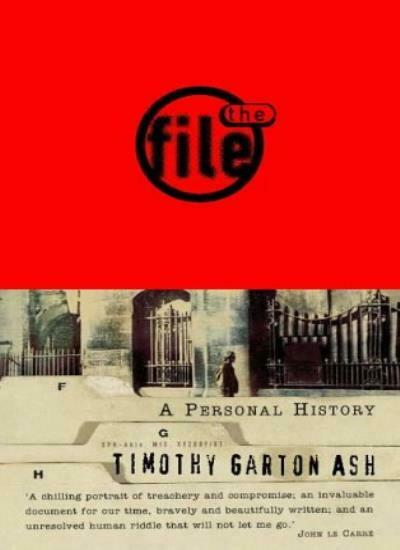

In the 1990s, the British historian and author Timothy Garton Ash wrote an entire book – titled unsurprisingly “The File” -- based on his own security file that was collected by the Stasi when Garton Ash was a student in East Germany in the late '70s. I read the book years ago and have only vague memories of it. I still recall, though, how strange and discomforting the entire ordeal had been for him, so many years later, to read through and discover all the mundane details of his life that had been so meticulously surveilled and archived. A couple of weeks ago, in mid-January, I had the first chance to read through my own file. I was happy to see that it confirmed the accuracy of the stories that I tell in Čas proměn, but I also know now much better that odd mix of emotions that Garton Ash must have grappled with. I'll flesh all of this out in more detail in future posts (and of course in any forthcoming English-language version of the book). Stay tuned.

With all the excitement going on with the book, I’ve found it hard to focus on my real job as a travel writer and journalist. For the moment, though, that’s not much of a problem, as there’s almost nothing happening. All of the guidebook titles I had so optimistically planned to write in 2020 (and 2021), on countries like Romania, Hungary and the Czech Republic, were abruptly cancelled once the expansive outlines of the coronavirus crisis became clearer. For the time being (as far as I know), they still remain on hold.

The future of my role as a Danube river cruise "destination expert" for National Geographic Expeditions is also unclear. Understandably, all of the cruises for 2020 and 2021 were eventually cancelled. Happily, I’m scheduled to work on two departures -- but not until 2023. I suppose we’ll have to see how that goes.

Over the Christmas holidays, I did receive a commission to write a magazine article on one of my favorite countries, Slovenia, for Boundless Magazine, which felt like a welcome return to routine. I also still get the occasional, odd job from Lonely Planet to update online content on Prague and other places. I’d welcome more of this kind of work, but who can say for sure when any of this bread-and-butter, travel-writer stuff is ever going to return?

My attention is now trained on the upcoming TBEX Europe travel blogger conference, set for mid-March in Marbella, Spain, where I'm scheduled to speak. It’s still officially a “go,” but it’s hard to imagine that this current omicron wave will dissipate quickly enough to allow for a big international conference like this one to safely take place. As one of the organizers, however, recently reminded me in a text exchange: “A lot can happen in two months.” Let’s hope any changes are good ones.

Strange name for a journal, “Cultural Stomach.” I kind of like it! Starts all sorts of meta connectivity going around (in my stomach). Or maybe you can’t always guess the meaning of words in one Slavic language by knowing another?

Kulturny zivot? That means “Cultural Life” :))

So glad to hear the news about the upcoming English version of your book! I’ll be first in line.

TBEX also looks interesting – one of these days I should get myself to a conference.

Thanks for the note and yes, you need to come to TBEX 🙂

Intrigued about the contents of your file! Also about Will Crisp’s view of BI. Glad the book is doing well.