Not long ago, I was cruising through reviews of my book,“Čas proměn,” on a Czech online database and my eye immediately caught a review written by a reader named “Iška.” I noticed she wasn’t exactly overwhelmed by my book (awarding it just three stars out of five), and then she doled out an extra dose of humility. She typed:

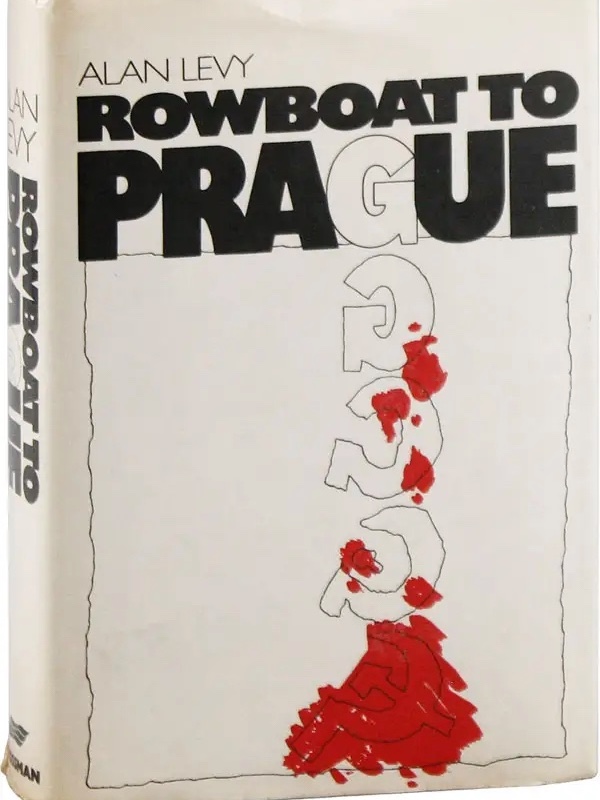

“It’s good to look at things from time to time through the eyes of someone who, thanks to his position from the outside, retains a certain perspective. But when I recall Alan Levy and his “Rowboat to Prague,” Gene Deitch and his “For the Love of Prague,” or “Gottland,” by the Polish author Mariusz Szczygieł, I have to say that I found this title (Čas proměn) to be the weakest.”

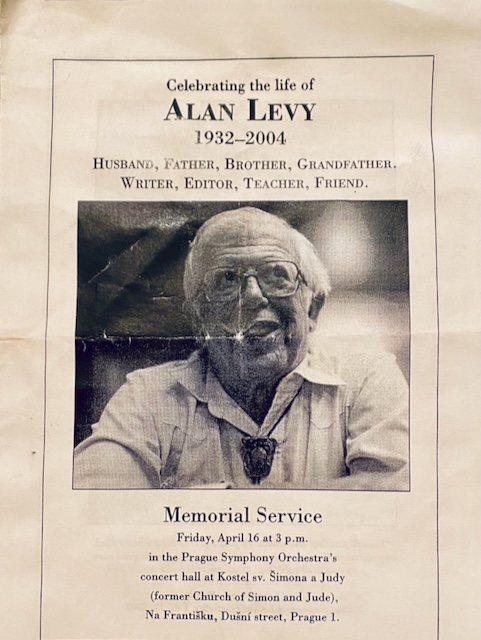

I laughed when I read it. You can’t win them all. And then I immediately thought about Alan. Not only would he have been proud to have his own book compared to Deitch’s and Szczygieł’s works (and rated a good notch above my own book), but I think he would have been over the moon at the thought that “Rowboat to Prague,” now 50 years removed from publication, might still be viewed by Czech readers as a gold standard in the genre of foreign authors writing about Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic.

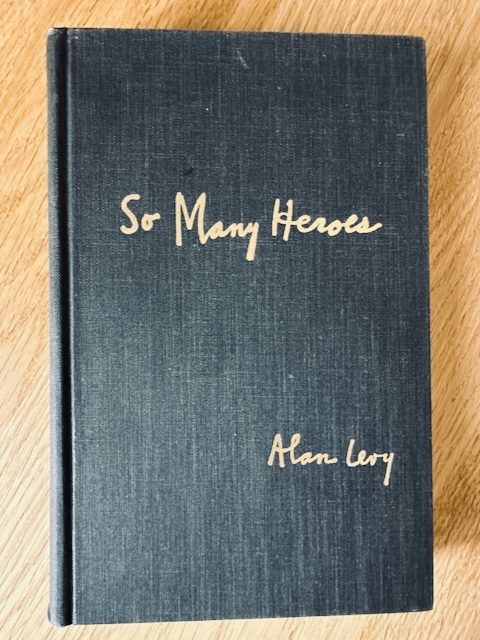

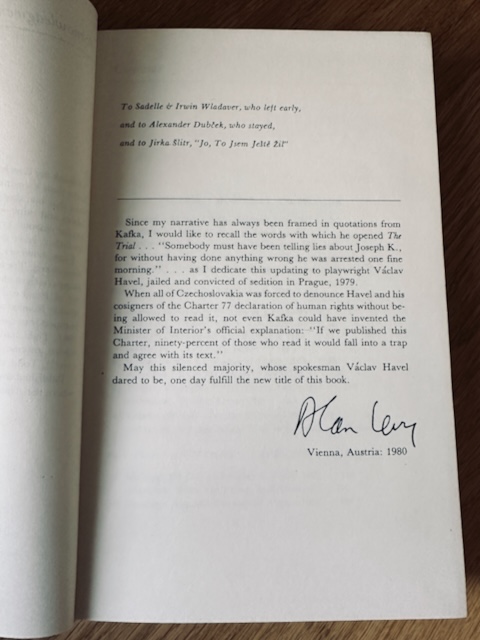

And as much as I hate to admit it, Iška might very well have a point. “Rowboat to Prague” is still a very good book. I keep a copy of it (I have the “So Many Heroes” imprint from 1980) close at hand and page through it regularly to refresh my memory of that fateful year of 1968 and to recall details of that frightful Soviet invasion, when thousands of supposedly friendly soldiers poured over the border and drove their tanks through Prague. It’s also useful in trying to relive the emotions --- the highs and absolute lows – that Czechoslovaks keenly experienced during that year. I found the book particularly useful in trying to wrap my head around Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

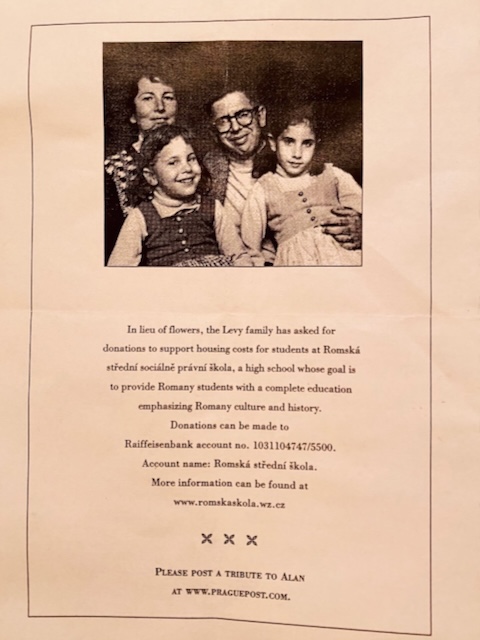

In case readers here are unfamiliar with Alan’s book, he traces events in Czechoslovakia from late-1967, when he and his family (wife Val and young daughters Monica and Erika) first moved to Prague, through the remarkable early months of 1968 and the rise of political reformer Alexander Dubček and stunning rollback of political censorship. Those were truly hopeful days. The book then moves to the tense month of August and the shocking Warsaw Pact invasion of August 21, 1968 (which Dubček himself didn’t see coming). Then comes the tragic denouement, as Dubček is deposed and new Soviet-backed leaders begin to implement the return of hardline communist rule.

In re-reading the book, I’m reminded that Alan’s writing was dense and granular in ways that I struggled with in writing my own book. He had a keen eye for detail and an ear for dialogue that immediately drew readers in. Indeed, much of the book is structured around conversation (Alan was writing about events that happened just weeks or months earlier, while I was often trying to recall events that happened 30 years ago). Whether Alan faithfully recounted every conversation or merely reconstructed dialogue from memory is not important. His narration still feels faithful to events and reactions in real time.

“Rowboat to Prague” was published in the U.S. in 1972. It was translated into Czech and circulated underground as “Pražské peřeje” a few years later. It won a wide Czechoslovak readership (that would serve him well later at The Prague Post). The book was celebrated in the U.S. at the time as a first-hand account from behind the Iron Curtain of an invasion that marked a key inflection point in post-war European history. As Newsweek reviewed it on publication: “[Levy’s book is] written with an intimacy of detail and emotion that transcends mere journalistic reporting.”

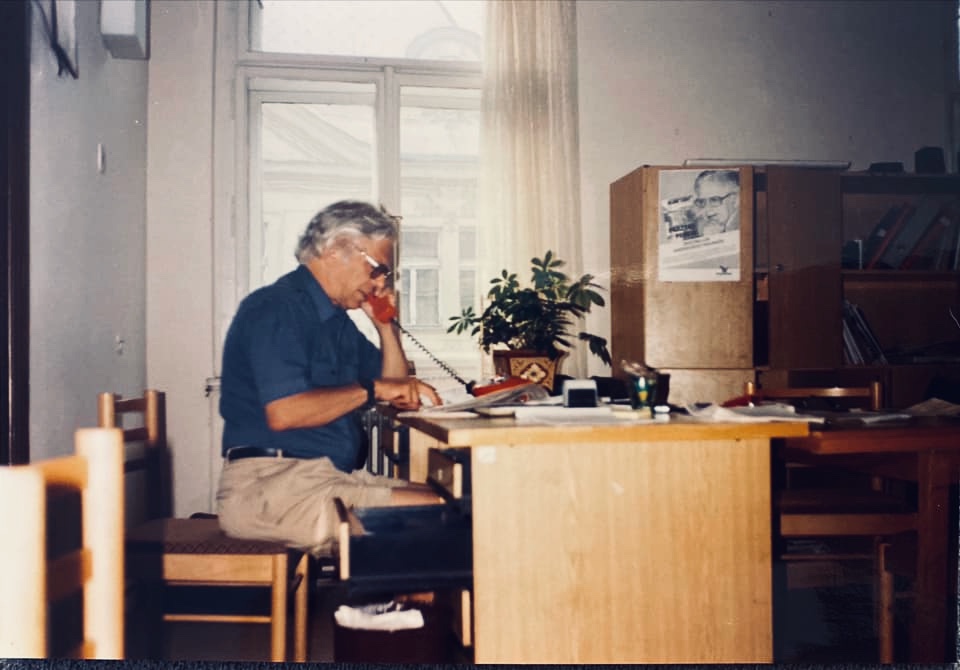

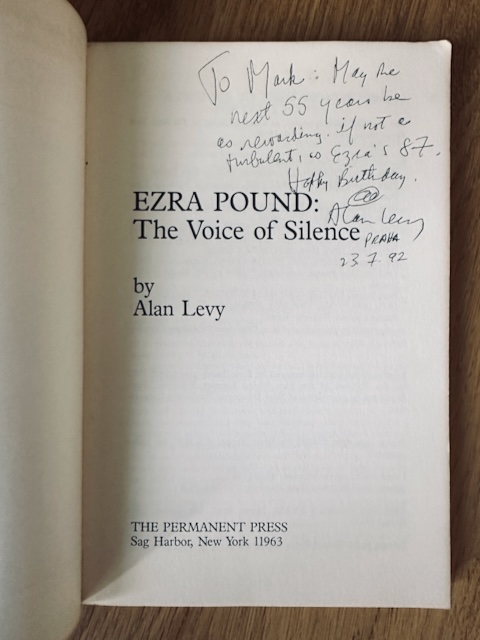

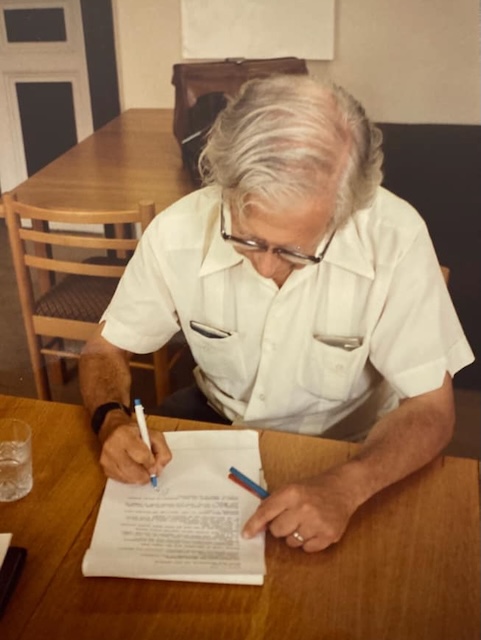

Alan tried to tough it out in dreary, post-invasion Prague for a couple of years -- using every trick in the book to stay -- before finally being expelled from the country in 1971. He and his family settled in Vienna, where our paths would cross 15 years later, when I first moved to the city to work as a journalist. My first-hand Vienna memories of Alan are faint; we ran in different circles. He was widely viewed, though, as a local celebrity. From what I can gather piecing together his time there, he spent his days alternating between working at Vienna’s excellent English-language theater and writing and publishing biographies on personalities as diverse as Sophia Loren, Ezra Pound, Vladimir Nabokov, and a Czech emigre to the U.S. named Karel Čapek. This last book, published in 1974 as "Good Men Still Live!," is notoriously difficult to track down and I've never seen a copy myself. For a brief period, around 1988, Alan hired my then-girlfriend, Delia Meth-Cohn, to help him transcribe his notes to those big 5¼-inch floppy disks that were all the rage back then.

Vienna was only ever going to serve as a place of exile. Alan would eventually make his way back to Prague through a series of dramatic events that neither he nor anyone else could have ever imagined or conjured up for a book. As a writer and dramaturge, though, Alan was quick to recognize the grand, theatrical elements of Czechoslovakia’s 1989 Velvet Revolution – which installed a playwright as president in Václav Havel -- and of his own comeback role in trying to right the historical wrongs of that earlier 1968 invasion.

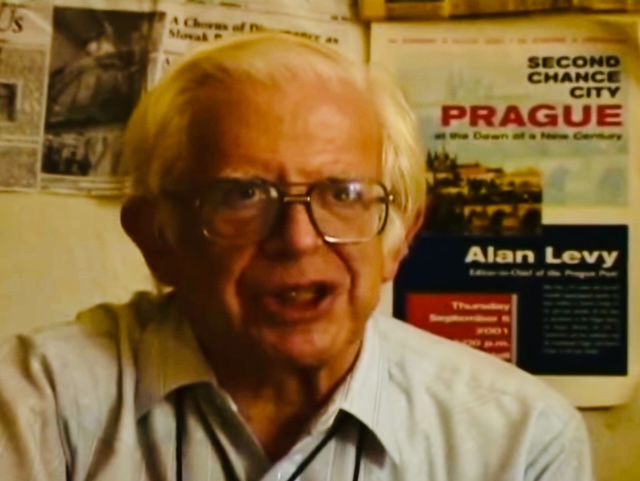

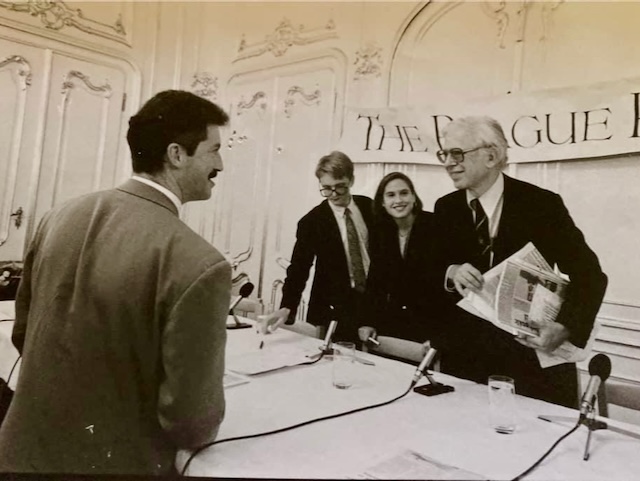

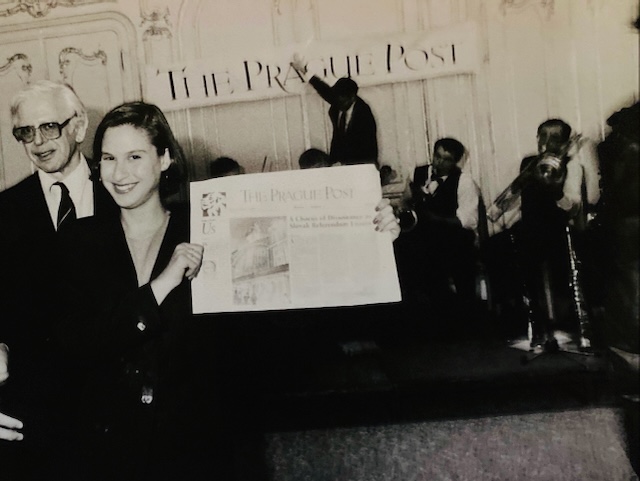

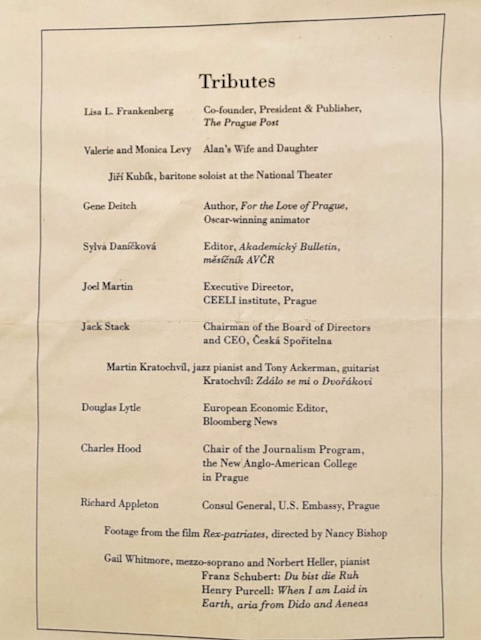

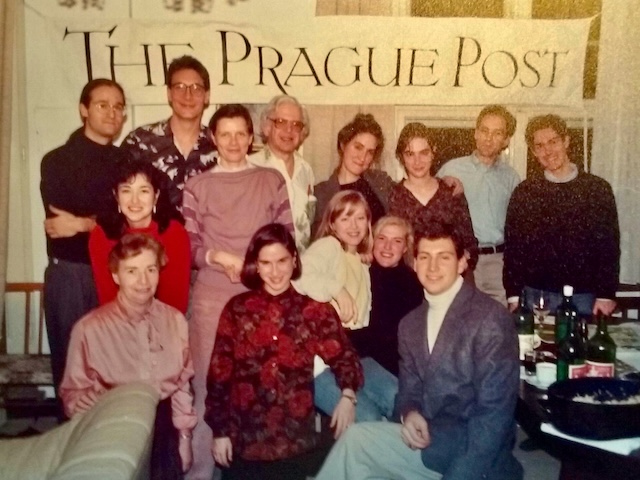

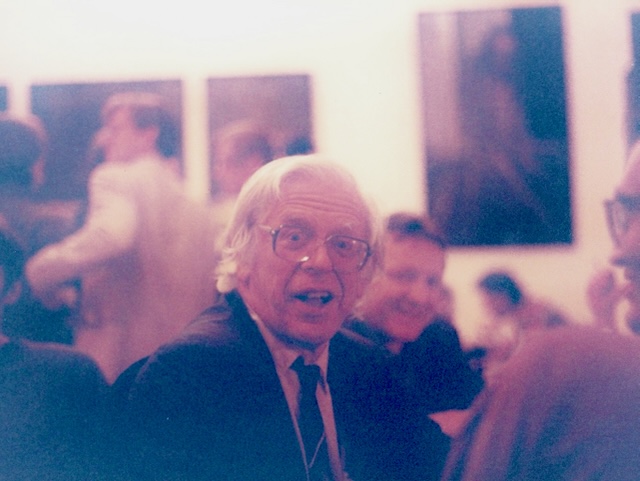

My first day-to-day memories of Alan began in the summer of 1991, when both of us found jobs at the newly formed Prague Post, one of two English-language newspapers operating in the city back then. I was hired to be the paper’s business editor, while he would be editor-in-chief. I felt an instant kinship. We were both “Viennese” migrants at a time when most English-speaking foreigners came directly from the U.S., Canada and U.K. I had also learned a bit about his character through Delia. I knew him to be ambitious, a talented writer, and a staunch defender of journalistic principles and of the wrongly accused (this latter probably stemming from his own unjust deportation). But he was also stubborn, fond of publicity, and had a soft spot for those big buffet spreads of ham, cheese and drink that always accompanied big press events back then. (I write this with great affection. Like all of us, he had his own virtues and flaws).

Alan’s qualities, on balance, served The Prague Post very well, particularly in its earliest days when the paper was trying to build up a local readership. Thanks to the samizdat editions of “Rowboat to Prague,” Alan was still close to being a household name among Czechs, which brought our paper instant recognition and legitimacy. Moreover, his ties to the 1960s and early-‘70s helped thematically to connect our paper – bridge the long gap of cultural sterilization that followed the Warsaw Pact invasion – to that last great period when Czechoslovakia had experimented with democratic freedoms.

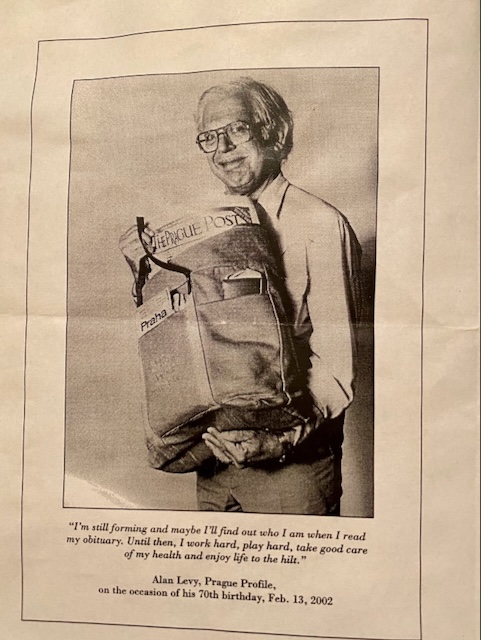

He leaned into that connection frequently and often used his weekly “Prague Profile” column in our paper to focus on individuals, including many Czechs, who like him had been wronged by the invasion and harsh normalization and had returned to the city to exact a form of karmic revenge. There’s a recurring theme in many of those early columns.

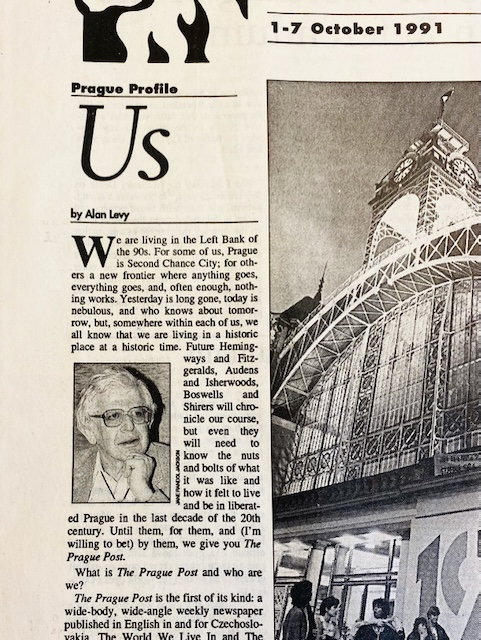

Of course everything didn’t always go smoothly. For his first “Prague Profile,” which appeared in the paper’s debut edition on October 1, 1991, Alan chose to write about “Us” – namely the young paper and its staff. The concept was to introduce our paper to readers, but Alan decided to go big picture (and off-script). Instead of sticking to this more-modest aim, he addressed the role of Prague itself in the new world order. In soaring rhetoric that compared post-communist Prague to the storied role that Paris once played in the 1920s, Alan declared the Czechoslovak capital to be the world’s “Left Bank of the ‘90s.” He boldly (brazenly) predicted that the generation of young foreigners who were then starting to move to Prague would go on to produce some of the world’s greatest literature.

This is what he wrote:

“We are living in the Left Bank of the ‘90s. For some of us, Prague is Second Chance City; for others, a new frontier where anything goes, everything goes and, often enough, nothing works. Yesterday is long gone, today is nebulous, and who knows about tomorrow, but, somewhere within each of us, we all know we are living in a historic place at a historic time. Future Hemingways and Fitzgeralds, Audens and Isherwoods, Boswells and Shirers will chronicle our course …”

I’ve written before on this blog about the explosion of expats who came to Prague in the early-1990s and of the encouraging effect these words exerted on a mostly-younger generation of roamers and dreamers around the world. Many of us at the paper, though, were mortified at the time by the column. Alan’s prophesy felt gaudy and way over-the-top. None of us seriously believed Prague would spawn a generation of young Hemingways (or even if that would be a good idea).

In retrospect, though, I’ve softened my view and now appreciate that column more. It’s true, Prague never quite lived up to the hype (though many good writers did come and write here at the time). These days, I see “Us” more as a love letter to the city and an urgent act of wish-fulfillment on Alan’s part. By trying to will Prague into becoming a new Paris, he was articulating a different kind of prophecy for the city: it would never again slide back into being the gray, lifeless capital of a satellite state. (In this less-ambitious respect, that prophecy came true).

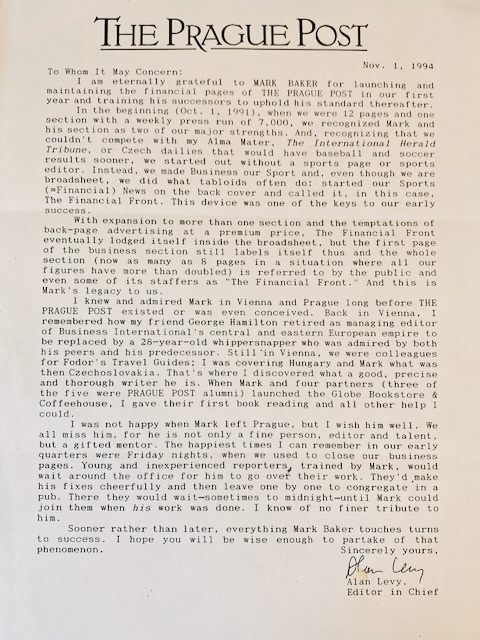

Alan was immensely loyal. Once you were in, you were in. That was reinforced to me shortly after I left the Post and decided in 1994 to return to the U.S. in order to (hopefully) further my career as a journalist. Alan very kindly agreed to write a recommendation letter for me that I could show to prospective employers. What he came up with was the nicest recommendation I’ve ever gotten:

“I was not happy when Mark left Prague, but I wish him well. We all miss him, for he is not only a fine person, editor and talent, but a gifted mentor. The happiest times I can remember in our early quarters were Friday nights, when we used to close our business pages. Young and inexperienced reporters, trained by Mark, would wait around the office for him to go over their work. They’d make his fixes cheerfully and then leave one by one to congregate in a pub. There they would wait, sometimes to midnight, until Mark could join them when his own work was done. I know of no finer tribute to him.”

I can’t remember now if any of this was as true as Alan makes out, but it was certainly proof he had my back. For that I was grateful.

Twenty years is a long time. Memories inevitably fade as new events quickly overwrite the old. Alan was passionately devoted to Prague and (twice) adopted the city as his homeland. The catch-phrase back in the day for Dubček’s reforms was “Socialism with a Human Face.” It’s no exaggeration to say that “Rowboat to Prague” put a human face on the country itself for a generation of English-language readers who might not otherwise know much about it or the grotesque invasion it had endured. Later, as editor of The Prague Post, he crafted a modern-day myth about Prague that helped to lure thousands of foreigners to the city to discover its charms and contribute to cementing its future.

Alan appeared at watershed moments in modern Czechoslovak history and used his tools as a writer to highly positive effect. For that, and many more things, he deserves to be warmly remembered.

To read more about Alan, click here to find the first of a two-part series on The Prague Post that I published in 2021 on the paper's 30th anniversary.

Wonderful tribute to Alan Levy and his contribution and place in time that ushered an era of creativity and energy on the “Left bank of the 90’s.” Alan was a true pioneer; many followed to embrace their own dreams and aspirations during that magical time in Prague. The memories may fade, but that ache in our heart for Prague lasts a lifetime. If you were there the 9o’s, you know that feeling never quite leaves you.

I was fortunate to cross paths with Alan on occasion. He didn’t know me, but I admired his work and thought it would be nice to say hello when opportunity arose.

I posted a link to this story and asked for some personal recollections of Alan. People sent me some nice ones, which I’m reprinting below:

Shortly after I started working at “The Prague Post” in 2001, I hosted an Easter Champagne brunch at my flat and invited everyone from the paper. Alan and his wife showed up with the biggest bottle of Champagne I’d ever seen. A man of youthful spirit, big gestures, and generosity.

– Jennifer Sokolowsky

He interviewed me twice for his Prague Profiles. Some alcohol was involved. Actually, lots of alcohol was involved. Alan could talk. And drink. He knew everybody. I’d meet an interesting person, ask Alan if he knew them, and not only did he know them, he’d tell stories about them. When he interviewed me, Alan’s word count tripled mine. He’d dominate the conversation through dinner and the first bottle or two of wine, and only then would he turn on his tape recorder to do the interview. I miss him.

– Robert Eversz

His “Nazi Hunter: The Wiesenthal File” is an amazing book. He described horrific things with such sparse clarity, letting the facts speak for themselves. Incredibly effective writing and a great read. His account of the heroic acts of Raoul Wallenberg in particular was both thrilling and heartbreaking. Alan himself was great fun, a compassionate human being with a great sense of humor. Enjoyed every minute I spent with him.

– Khatya Chhor

I have so much love for him, and the inspiration he gave us. He used to call me “Jackie Kerouac.” He read some of my early short stories and gave me his trademark, direct impressions. Much appreciated and honest, they helped me to become the writer I am, and not to continue writing like someone else (looking at you, Hemingway!). Thanks for sharing these respects, Mark

– Marion Blackburn

His wife, Val, was a dear friend of, mine so much of what I learned about his achievements, I learned from her. May they both RIP.

– Janet Lynn Feinstein

Alan made the decision to hire me as chief copy editor (we’d be working closely, especially the long Mondays) in 1996. He taught me a lot and helped me hone a gimlet eye for detail, and the bigger picture too. Late Monday, when we were done, we’d amble over to Saint-Jacques to share a fondue. Learned a lot about where I was. Remember Paloma? Sometimes we’d get a group together for tiramisu. Val was a delight.

– Dennis Moran

Levy was a friend of our family and my mother was in frequent contact with him, he published some articles about our family.

– Ivan Margolius

He was quite an original! Thankfully I have a few of his books here in my collection.

– Kurt Vinion

You captured him beautifully, Mark. He would have loved it, and I know how proud he was of you. I was verklempt reading this and am really missing him right now. He gave me a full set of his books and I do have a copy of “Good Men Still Live!” if you ever want to borrow it.

– Lisa Leshne

Really well done…I read “Rowboat to Prague” long before my move to Vienna. Found it by chance at the NYPL.

– Cara Michelle Morris

Great photo of the offices that captured that era so well, and the work of reporters who pushed to tell the story of Prague back then, especially Levy.

– Liz Smith