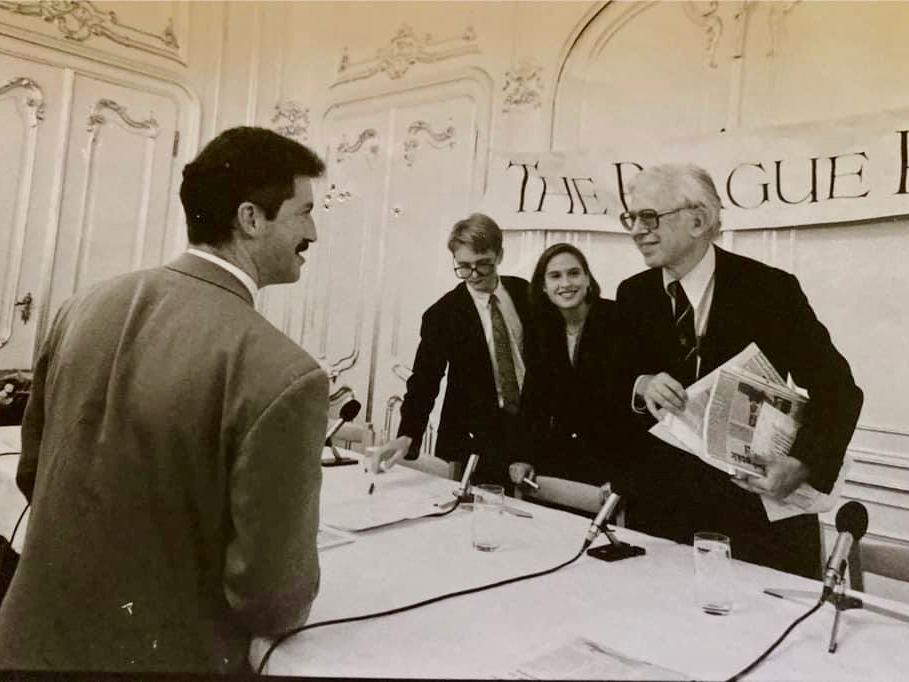

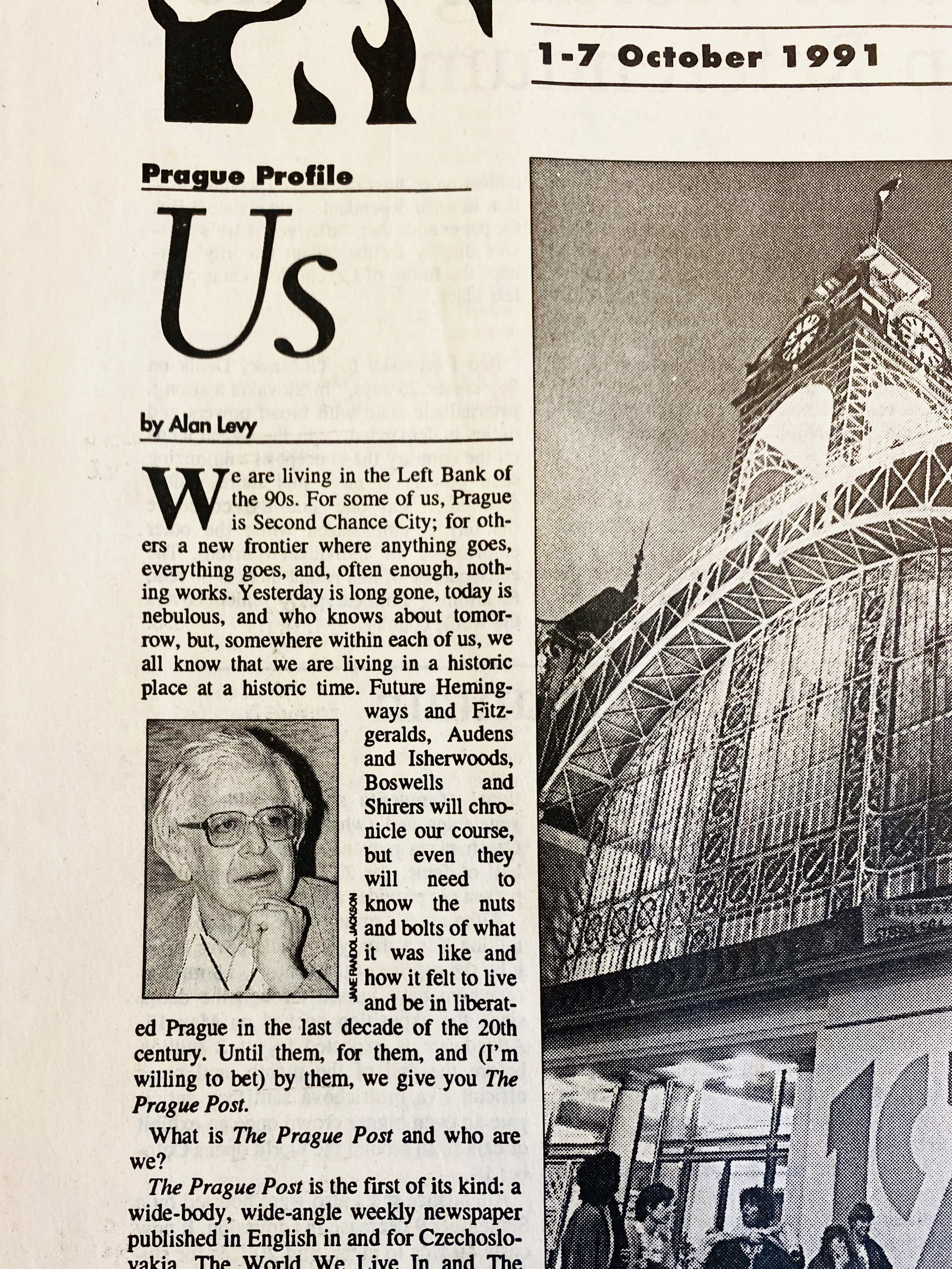

It’s difficult to put a precise date on when this expat influx began, but a strong contender might be October 1991, when a certain irresistible catch-phrase about Prague (and the title of this post) was let loose into the wider world. At the time, I had recently moved to Prague from Vienna and had just started working as an editor at one of the city’s newly minted English-language newspapers, The Prague Post. As we prepared to launch our first issue on October 1, 1991, our paper’s editor-in-chief, Alan Levy, penned an essay, titled “Us,” for the front page that was intended to introduce the new publication to readers and to let them know what to expect.

Instead of sticking to this more-modest aim, though, Alan chose to address a bigger theme: the role of Prague itself in the new world order. In soaring rhetoric that compared post-communist Prague to the storied role that Paris once played in the 1920s, Alan declared the Czechoslovak capital to be the world’s “Left Bank of the ‘90s.” He boldly (brazenly) predicted that the generation of young foreigners who were then starting to move to Prague would go on to produce some of the world’s greatest literature. This is what he wrote:

“We are living in the Left Bank of the ‘90s. For some of us, Prague is Second Chance City; for others, a new frontier where anything goes, everything goes and, often enough, nothing works. Yesterday is long gone, today is nebulous, and who knows about tomorrow, but, somewhere within each of us, we all know we are living in a historic place at a historic time. Future Hemingways and Fitzgeralds, Audens and Isherwoods, Boswells and Shirers will chronicle our course …”

On its face, Alan’s comparison of Prague to Paris appeared ridiculous. Paris’s “Lost Generation” of writers and poets included towering literary figures like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ezra Pound, who’d authored some of the most-important books of the 20th century. Alan wasn’t the first person to compare early-90s’ Prague to Paris’s Left Bank. The American journalist John Allison, for one, had made a similar observation, more jokingly, in an essay for the American publication, Hungry Mind Review, a few months earlier. Alan, though, was the first to coin the phrase the “Left Bank of the ‘90s” and that was the expression that stuck.

At the paper, we quietly mocked the Left Bank analogy as a slick piece of marketing or a bit of self-serving bluster. The words felt gaudy and overblown (even back then). None of us seriously believed Prague would spawn a generation of Hemingways or Isherwoods (or even if that would be a desired outcome). But deep down we also acknowledged that not everything about the comparison sounded entirely false. That earlier Paris generation, after all, arose out of the ashes of World War I. Similarly, the anticommunist revolutions of 1989 shattered the political order of its own age. The fall of communism at the time was celebrated as the defining historical event of the modern era. The philosopher Francis Fukuyama even argued that the end of the Cold War marked the “end of history” itself. The 1989 revolutions, he reasoned, had demonstrated the superiority of Western-style democracies and heralded the beginning of a new global moment. Surely, the logic followed, such an important period might also inspire a new generation of thinkers (and maybe writers too)?

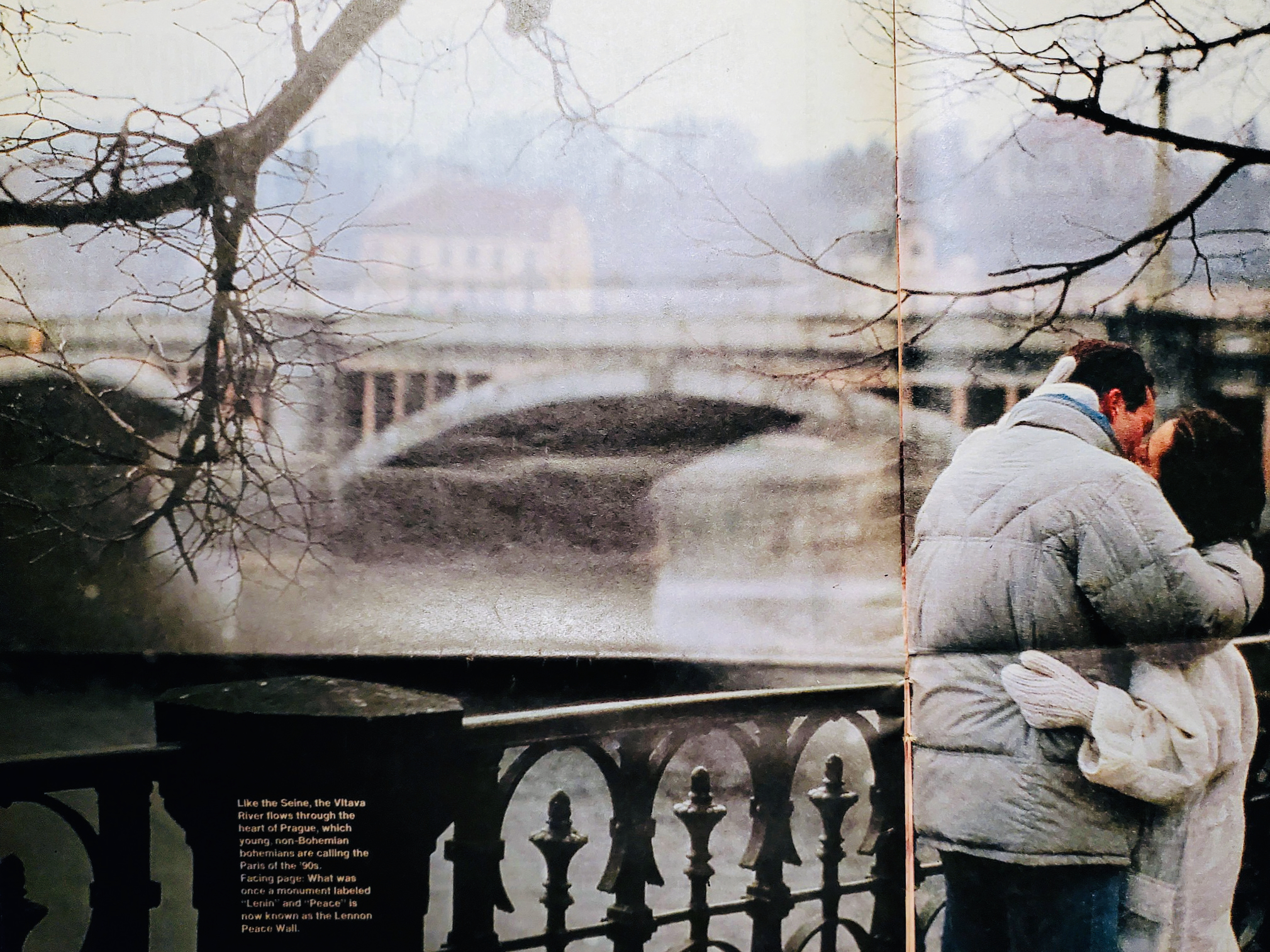

Prague, which stood at the center of the changes, seemed as logical a place as any to host these new thinkers. Part of the city’s appeal was the fairy-tale nature of the Velvet Revolution itself and the popularity of Czechoslovak President Václav Havel. The revolution, in its retelling, sounded almost too good to be true: a peaceful transfer of power led by intellectuals and students who’d toppled an evil dictatorship and established a playwright as president. It was a powerful refutation of cynical politics and an apparent, real-life validation of Fukuyama’s own theory. And then there were Havel’s famous friends: musicians like Lou Reed, Frank Zappa, Mick Jagger and others. Prague felt like the coolest capital on earth.

An even bigger part of Prague’s attraction might have been the city’s own mystique. Many of the new arrivals, like me, had come of age reading the early novels of writers like Milan Kundera, whose stories – whatever one might think of the author himself – bestowed on the city (and country) a gloss of wit and sophistication. Similarly, the towering figure of Franz Kafka – whose likeness was suddenly, shamelessly peddled on T-shirts and coffee mugs – infused the capital with a sense of mystery and foreboding. Kafka’s time had clearly come and gone, but the mere fact the author had lived and worked in Prague subtly encouraged a generation of young, wannabe writers to believe that immense literary truths could still be mined, like pieces of gold, from beneath the city’s cobblestoned streets. Prague’s beauty – the hypnotic, visual tension between bridge and castle – only added to the allure. The Left Bank, after all, was a conscious allusion to Paris. Of all the newly democratic cities of the former Eastern bloc, only Prague could dare compare itself to the French capital in terms of physical appearance.

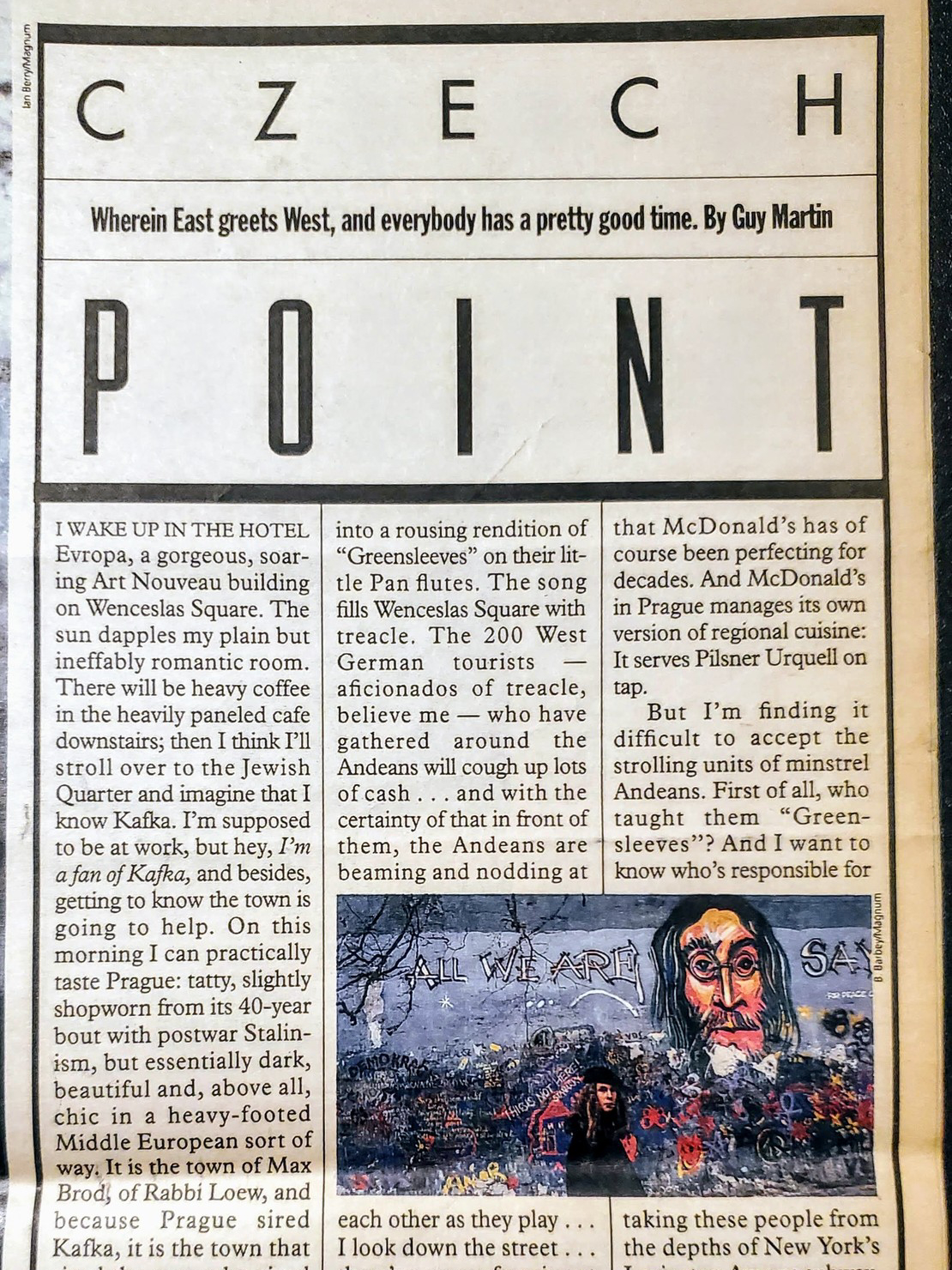

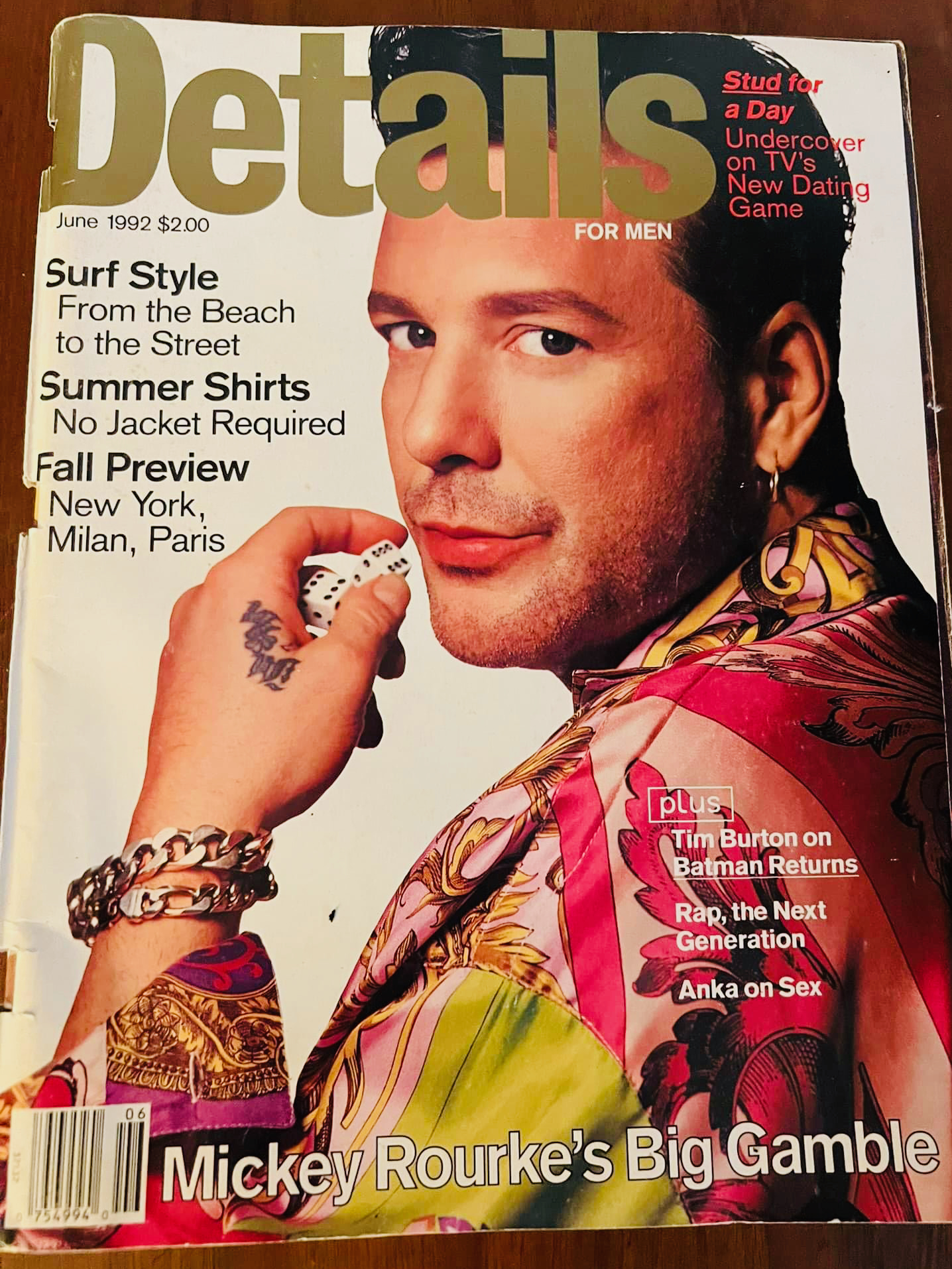

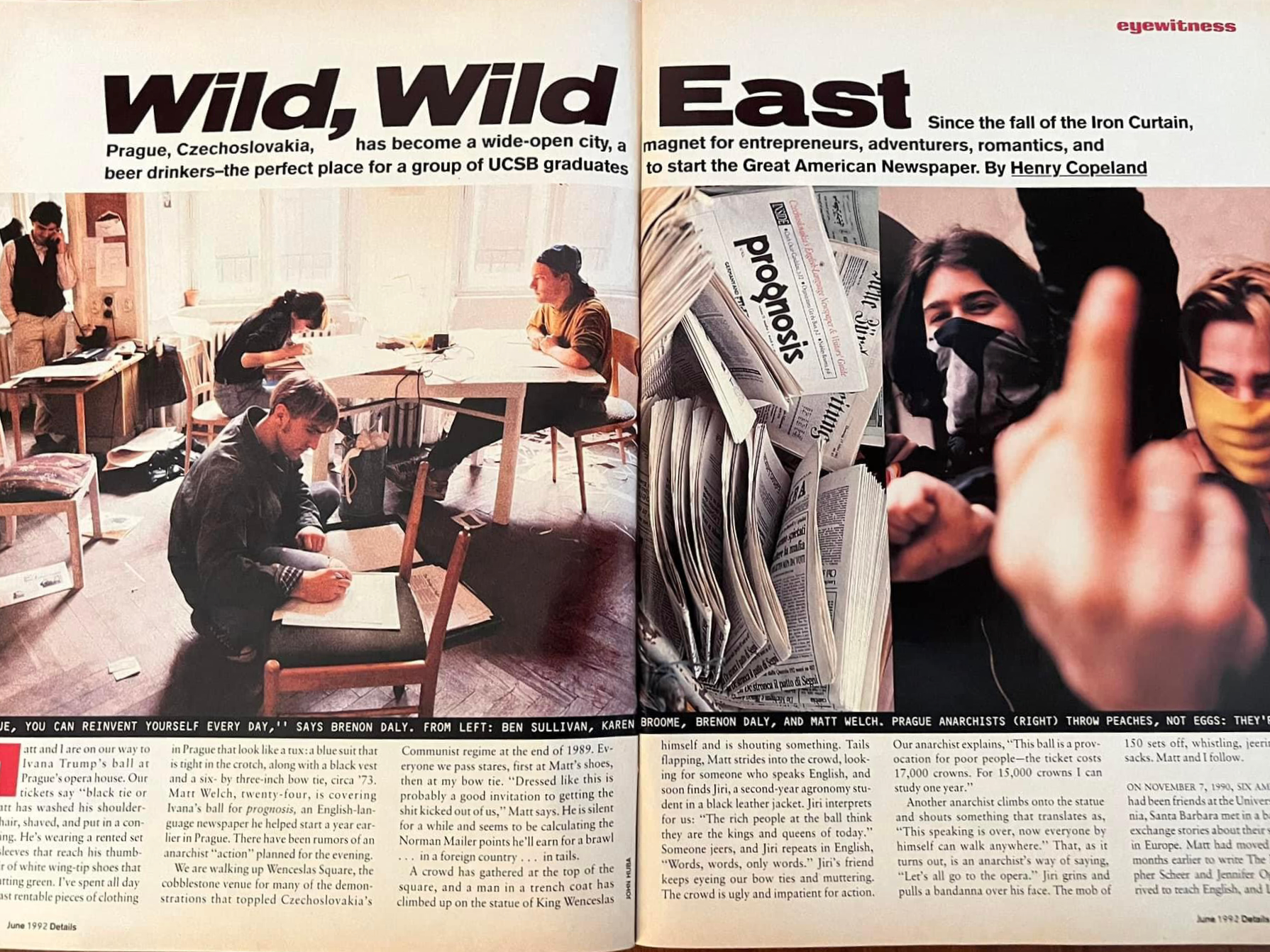

It didn’t take long for Alan’s lofty words to circulate beyond the borders of Czechoslovakia. His Left Bank analogy quickly reached the publishing capitals of London, Toronto and New York, where it fired the imaginations of newspaper and magazine editors everywhere. Many of them, of course, were no doubt highly skeptical of Alan’s assertion that Prague would spawn a new “Lost Generation,” but his more-modest claim that “we are living in a historic place at a historic time” rang true. Glowing stories of Prague’s renaissance appeared on newsstands around the world. Those first stories inspired an early wave of readers to come to Prague to see what all the fuss was about. That wave generated more media coverage, which in turn brought even more people. The influx evolved into a self-fulfilling prophecy. (I've posted photos here of some of the bigger newspaper and magazine stories -- but there were dozens more).

As a quick aside, it’s worth recalling that Prague wasn’t the only city in the former Eastern bloc – or even Czechoslovakia – to experience a surge of expats in the 1990s. Brno had its own influx, though smaller than Prague’s. Outside the country, cities like Budapest and Kraków experienced their own Left Bank moments too, though the foreign communities there grudgingly admitted their own scenes weren’t perhaps quite as significant. The American writer Arthur Phillips, who spent the early-‘90s in Budapest, bestowed the ultimate compliment on Prague in his fictionalized account of Budapest’s expat scene, which he published in 2002. Instead of calling his book “Budapest” or “Danube,“ or some other reference to the Hungarian capital, Philips titled his novel Prague. When later asked about the book’s misleading name, Phillips said Prague represented the “unfulfilled emotional desires” of his characters; the city was viewed with envy as having more life and better parties.

No one knows precisely how many people eventually relocated to Prague between 1991 and about 1996, when the wave of new arrivals began to taper off and the initial luster of the Left Bank metaphor started to dull. Rough estimates at the time put the number (optimistically) anywhere from 30,000 to 50,000. A large percentage were Anglophones, from the US, UK and Canada, though the city’s allure also attracted wanderers from countries closer to home, like Germany, Italy and France.

Not all the newcomers came to write books, poems and plays. That early group of arrivals also numbered hundreds of lawyers, accountants and bankers who came to help restructure the economy and privatize the formerly state-owned companies. They also included Peace Corps volunteers, English teachers, experts in city government or urban planning, and, of course, hundreds of aspiring journalists who dreamed of writing for the Post or another popular English-language paper at the time, Prognosis. The reach of Prague’s foreign community eventually extended to nearly every part of the city’s cultural, economic and political life.

The most visible group of newcomers were individuals, like the founders of The Prague Post, who’d been lured to the city by the economic promise of the “Wild East,” a play on the old American Wild West. They came to start businesses and (hopefully) build fortunes. Even as Alan’s “Left Bank” essay appeared on newsstands, the first group of these early economic pioneers was already arriving. In early 1992, a Canadian arrival, Glen Emery, was then hunting space to house the city’s first expat-owned bar, which later became Jo’s Bar. Another foreigner named Glenn, this one American Glenn Spicker, announced plans to open a new American-style restaurant, Red, Hot & Blues, in Prague's Old Town.

Outside the center, a recent American arrival, Grady Lloyd, had already opened a self-serve laundromat, Laundry Kings, billed as the first of its kind in the former Eastern bloc. These early ventures were soon joined by dozens of other expat clubs, bars and restaurants: Radost FX, The Derby, Little Glen’s (U Malého Glena), Tam Tam Club, Ubiquity, Jáma, The Thirsty Dog, and many, many more.

Early-‘90s Prague was highly attractive terrain for these budding entrepreneurs. Not only did the fall of communism open up vast, untapped markets for Western-style goods and services, but the initial chaos that followed from the Velvet Revolution had weakened the country’s bureaucracy, including the police, immigration services, tax collectors and ministerial offices. This short-lived crippling of the state, in fact, had been a crucial part of the scene’s vitality (it put the “wild” into the Wild East). Many early expat businesses (and plenty of locally-owned ones too) were able to open quickly without first having to obtain operating permits. Spot checks by the authorities were rare. This same sense of lawlessness, of course, pervaded other aspects of society and the economy – including the country’s uneven privatization process – and the results weren’t always favorable.

Despite this pervasive sense of chaos, the reaction of the city’s Czech population to the flood of foreigners was almost uniformly positive (at least in my recollection). This was long before Islamic extremism in the early-2000s and the migrant crisis of the 2010s turned many people against inward migration. Most Czechs, in the early days, warmly embraced the newcomers and the know-how, enthusiasm and cash they brought with them.

Younger Czechs were invariably the most welcoming. They, of course, were busy opening up their own bars and clubs, with names like Bunkr, Borát and Belmondo. The local and expat scenes freely intermingled and co-existed. My friends and I spent as much time at these Czech-owned places, or at local student haunts like Hogo Fogo and Blatouch, as we did in the new expat-run bars.

To be sure, a small portion of the local population, usually communist holdovers or supporters of an early, fringe anti-immigrant party, the SPR–RSČ, headed by Miroslav Sládek, resented the arrivals. We also occasionally heard disturbing stories of Czech skinheads or neo-Nazis who attacked Asian or black individuals – whether they were local or foreign-born. The vast majority of people, though, regarded the newcomers as either a net benefit or at least an acceptable price to pay for the freedom to travel or live abroad that Czechs and Slovaks themselves now enjoyed.

(Next week, in Part 2, I write about when the wave crested and the party eventually came to an end, and what, if anything, we can make of that time looking back from today.)

*Some readers may balk at the term “expat,” which has fallen out of favor in some circles in recent years. I acknowledge the word might carry with it the notion of privilege, but I’ve retained it here as the term commonly in use at the time. By “expat,” I refer merely to a person who has chosen to leave his or her home country but without necessarily the intention of staying away permanently.

RE Left Bank. I first droped into Prague in 1992 on college backpacking trip. Dont remember much. But since the early 2000’s I have been stopping by for a long weekend regularly, at least once a year. You are article highlights the lighter side. I spent a month there in Jan 2011 learning to teach English. Other capitals were having their own revivals. Some like Warsaw had other problems like surges in crime before they found their place. What about the darker side of Prague during this time? The movie Loners (2000) comes to mind. I saw it at a movie night at Sir Tobbys hostel as I recall.

Thanks for leaving a comment! I wrote a little bit about the darker side … many people don’t remember that whole skinhead thing of the early ’90s, but it was real and scary for anyone who didn’t look Czech and white. Mark

I moved to Czechoslovakia in February 1992. Arriving at a rather grim Florenc bus station, I was met by a couple of friends and we retired to a bar near the station to toast my landing. When it came to paying, the waiter tried to rip us off by insisting we had drunk ‘special beer’, which cost double the price of the stuff served to locals. It was an inauspicious start to what would be a wonderful time. Looking back, much of the wonder, I think, came from the fact that the country at the time was at the confluence of two rivers. One was filled with the heady waters of the freedoms won in the revolution. The other was filled with the somewhat anarchic void (if a void can fill something) created by the shifting from one political system to the other, and the fact communism had instilled in many Czechs contempt for rules and regulations. The first river is still there, although no longer appreciated in the same way. The other has gone, I am sure. I taught English in the state school system. On my first day at work, which was also the first day of the new term, I got to the school some time before 8am on a bitterly cold February morning, only to find the deputy director of the school barring my way to the staff room with a tray of glasses and a bottle of vodka in his hands. Every member of staff had to down a shot before they were allowed in. That behaviour was born from the second river, and I guarantee it no longer takes place.

It was all a sham and a scam. Nothing of any interest came of it. Canadians? They’re like Mormons or Scientologists but creepier and cultier. Just sad, sad, sad. Over hyped media event that carpetbaggers exploited. What’s wrong with America? Too much hype and exploitation. So why go to a place with even more. Should have gone to Berlin. It’s turned into something even worse now but I would have self-destructed years ago and be gone from this world. Definitely self-destructing in the right way in the right place is the thing to do. Christ said live like him but I couldn’t have gotten job training to become a carpenter because Reagan eliminated training in trades to force young men into the military to build his shining city on a hill. Walk around Prague now and the things shining brightest are souvenir shops. Why get a souvenir of something you’d rather forget.

Hi James, that’s pretty harsh (or funny, I couldn’t tell which). Did you read the post? Mark