In early 1991, I resigned my position at Business International in Vienna and relocated permanently to Prague in June of that year. I appreciated my job in Vienna and the opportunities it gave me to write and travel. By this time, though, all the energy and excitement on the European continent had clearly shifted to the other side of the old Iron Curtain. I wanted to experience that energy for myself.

Prague, on my arrival, glowed in early-summer sunshine. The first signs of the city’s tourism renaissance – the souvenir shops, sightseeing tours and room-finding services – sprouted around Old Town Square like snowdrops after a forty-year winter. The number of tourists that summer was noticeably larger than in previous years but still modest compared to what future seasons would bring. Within a year – though no one realized it just yet – a new wave of visitors would start arriving in Prague. These weren’t tourists exactly, but rather thousands of young people from all around the world who were drawn to the city by the enduring popularity of the country’s president, Václav Havel, and the romantic notion – part real, part hype – that Prague was a modern-day version of “Paris” of the 1920s. I focus more on this strange, exciting expat “invasion” in Part 2 of this post.

For the first time in years, I was unemployed and free as a bird. I found a black-market apartment in Prague’s Old Town, enrolled in a Czech-language class for foreigners and started to make my first local friends. One of those new acquaintances was Lisa Frankenberg (Leshne), an ambitious American in her 20s who had moved to Prague a few months before I did. She told me about her goal of starting a new English-language newspaper, The Prague Post. Not long after we met, she asked me to join the paper as the business editor. I wasn’t sure that I wanted to leap back into journalism so quickly, but I needed the work (that Old Town apartment wasn’t cheap) and eventually said "yes."

When I first accepted the offer, I figured the job would be easy. I thought we’d be covering what amounted to a “feel good” story: Czechoslovakia’s triumphant return from communism. Instead, the 12 months that I worked at the paper, from October 1991 through the following September, turned out to be one of the most turbulent periods ever in the country’s history. Over that brief span, Czechoslovakia rolled out a controversial law to rid the leadership of former communists; embarked on an unprecedented experiment to convert millions of citizens into company shareholders; and finally split apart into two separate countries, divided by powerful forces that proved impossible to stop or slow. Just a year from the day in late-July 1991 when I told Lisa I would join the paper, Czechoslovakia’s fabled playwright-president, the world hero of the Velvet Revolution, Václav Havel himself, resigned his office in despair. This chapter is about that roller-coaster year at the Post, where we chronicled those historic events and experienced, together with our readers, the emotional highs and lows of the times.

Looking back now on those first, early years after the Velvet Revolution, what’s often forgotten is just how uncertain and stressful they really were. That bright summer sunshine on my arrival had blotted out the dark shadows that were still lurking in the corners. The country’s new leaders faced seemingly intractable problems. Some were common across the whole of the Eastern bloc; others were unique to Czechoslovakia’s own history. Aside from the big, geopolitical question that hung over the entire region of whether the political gains made in the 1989 revolutions would survive, all of the countries wrestled with the common problem of what to do with the thousands of deposed communists and individuals who had collaborated with the old regimes. Should former leaders and informants be allowed to hold public office and other positions of authority or should they be blacklisted and banned? In Bucharest, the previous year, I saw first-hand just how passionate that fight could be. Romania’s failure to limit the activities of former communists there had sparked massive pro-democracy demonstrations and led to a bloody crackdown in June 1990 that I (and my girlfriend at the time, Delia) had inadvertently walked into.

The former Eastern bloc countries also confronted the daunting challenge of how best to transform their old state-run, centrally planned economies to compete on world markets. The Velvet Revolution had fully opened up Czechoslovakia’s industry, for the first time in decades, to international competition. Many of the old state-run enterprises had been artificially supported by the communist regime. Mass closures would lead to big job losses. The Czechoslovak crown, similarly, would now be allowed to float freely on international currency markets. Officials feared that any big drop in the crown’s value would raise the cost of imported goods and spark a disastrous rise in consumer prices.

Closer to home, the Velvet Revolution reopened historic wounds between ethnic Czechs and Slovaks and rekindled aspirations among some Slovaks to have their own state. While no one seriously feared that this disagreement would ever spill over into war, the situation then unfolding in Yugoslavia showed clearly how powerful and destructive unbridled nationalism could be.

As all this was happening, deep cracks started to appear in Czechoslovakia’s fragile political consensus forged in the heat of the anticommunist revolution. The fractures appeared not only between Czechs and Slovaks, but also within the respective umbrella organizations in each republic, “Civic Forum” in the Czech lands and “Public Against Violence” in Slovakia, that had collectively governed the country since the Velvet Revolution. Civic Forum, in particular, was riven by deep personal and philosophical differences. The group’s leading economist, and the country’s then-finance minister, Václav Klaus, pushed hard for a rapid, radical shift to a free-market economy. Klaus famously declared – at that economic conference in 1990 I had attended and on several other occasions – that he wanted to build a market economy “without any adjectives.” That expression was initially interpreted to mean that he strongly rejected communism and central planning, but Klaus’s philosophical objections to adjectives went deeper. He strongly opposed any economic policy that would help to soften the harder edges of the transformation, such as guaranteeing full employment or price stability. In Klaus’s view, these desirable qualities would flow naturally once fully-functioning markets were created. Klaus’s market orthodoxy put him at odds with other prominent leaders, including Havel himself. In early 1991, Klaus withdrew his free-market faction from the ruling Civic Forum and formed a new political party, the Civic Democratic Party (ODS). ODS soon emerged as the dominant political grouping in the Czech part of Czechoslovakia.

I’d like to be able to write here that I was alarmed by the break-up of Civic Forum and the appearance of competing political parties, but that was simply not the case. I (and many others) initially welcomed the splintering of these big political umbrella groups into individual political parties as a sign that Czechoslovakia was simply becoming a “normal” country. I reasoned it was healthier for people to be able to see and evaluate political and philosophical disagreements than to be blinded by any projection of false unity. In retrospect, I now see the developments differently. Those early disagreements between leaders ran so deep – and became so personal – that they divided people into competing camps and hampered collective efforts to solve big problems. At The Prague Post, we saw up close the heat those battles generated. Despite our best intentions to remain impartial, we often found ourselves unwittingly dragged into the country’s biggest post-revolutionary fights.

The Prague Post’s opening celebration held at the beautiful, baroque Pálffy Palác, on the evening of October 1, 1991, was a magical affair. The paper’s owners, which included Lisa and another young American expat, Kent Hawryluk, as well as a Texas-based fund manager, Monroe Luther, must have blown half the Post's annual budget on food and drink and renting out the building’s elegant chambers. The paper’s small, young staff, mainly American transplants like me and a sprinkling of Czechs, mingled with the guests. These included members of the local Czech journalism elite and more than a few expat wanderers, who came mainly for the free beer and wine. The crowds spilled out of the palace and onto the quiet lane out front to enjoy the surprisingly warm, autumn evening.

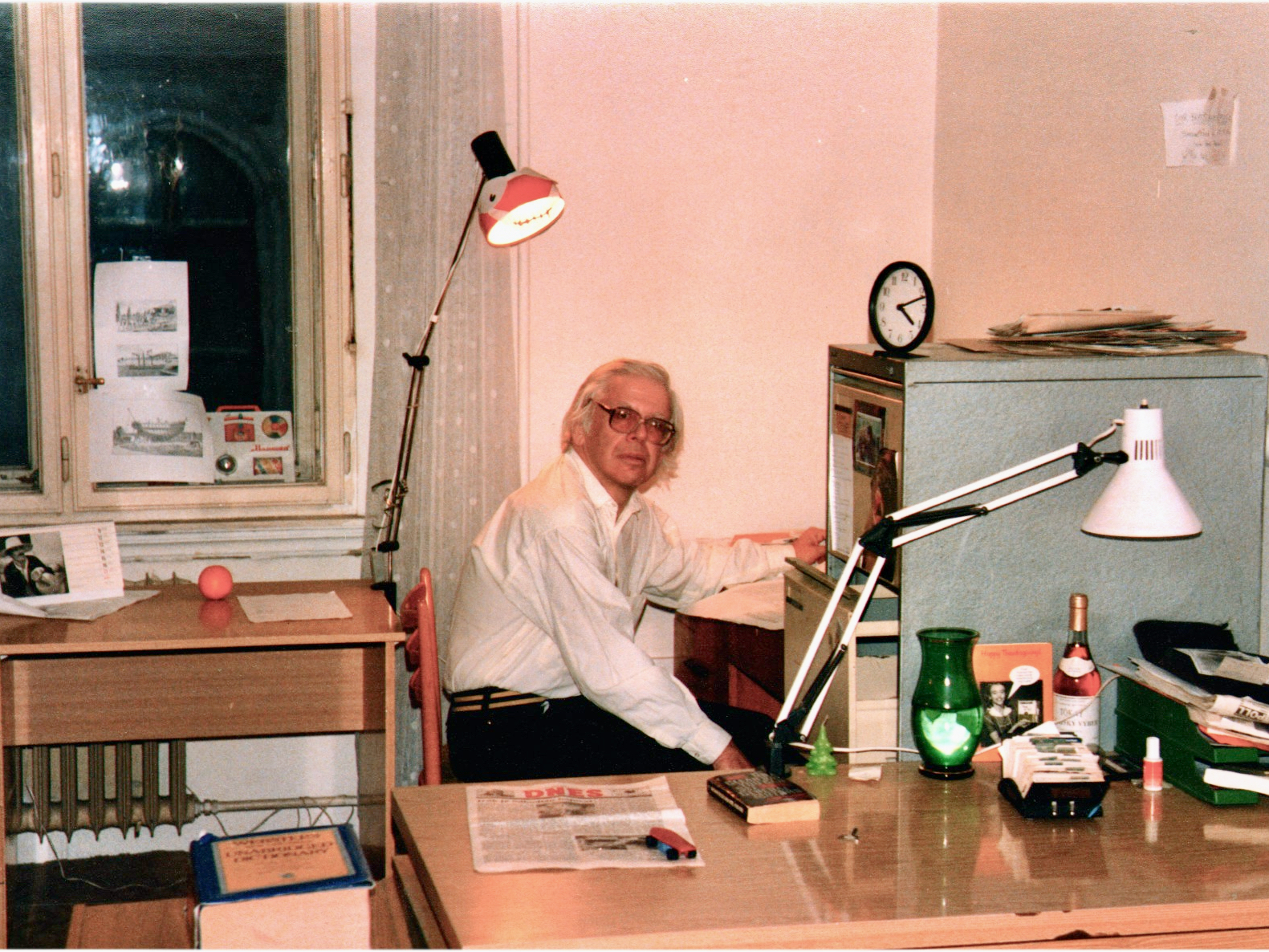

The star of the party was the paper’s Editor-in-Chief, the American journalist Alan Levy. Alan, who was 59 at the time, was by far the oldest member of our staff and the only one who enjoyed any name recognition among average Czechs. He had lived in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s and experienced the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion firsthand. His 1972 account of those events, Rowboat to Prague (later reprinted as So Many Heroes), was widely read and respected. In the aftermath of the invasion, the communists had expelled Alan and his family, and they eventually resettled in Vienna. During the ‘80s, when Alan and I both lived in the Austrian capital, I would occasionally run into him at the city’s English-language theater, where he worked as a dramaturg. He had even once hired Delia to help him transcribe his notes onto computer disks. Alan viewed his return to Prague as part of the city’s (and country’s) wider post-communist redemption story, and he reveled in the attention that night.

The Post wasn’t actually the city’s first English-language newspaper. That distinction went to our arch-rival, Prognosis, which was founded earlier in 1991 by students from the University of California Santa Barbara (and continued to publish until 1995). Prognosis had hired talented journalists and printed incisive, entertaining stories, but it looked much more like a student paper than the publication the Post’s owners wanted to create. Prognosis also had the disadvantage of being a monthly (at the time) and oriented more toward long-form features than hard news. The Post, by contrast, would be a weekly and structured much more like a traditional newspaper, with clearly delineated news, business and culture sections.

The launch generated a lot of positive buzz, and the Post’s early editions proved to be popular with both readers and advertisers. The success of those first editions validated the assumptions of the owners, Lisa and Kent, that Prague could support a second English-language newspaper. As the Post prospered, several new, talented reporters from the US, UK and Canada joined the staff, and the paper soon outgrew its cramped, one-room office near Old Town Square. Around Christmas that year, Lisa and Kent announced they had found spacious new offices nearby in Prague’s New Town. We were initially thrilled by the news, but our enthusiasm cooled once we learned that our new landlords would be the widely detested Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM). Indeed, the offices were located inside the party’s national headquarters. The Post always ran on a shoe-string budget, and the building at the time offered some of the city’s cheapest commercial space.

The Post’s move added a comical footnote to the history of Czechoslovakia’s post-communist transition. For more than a year, the successor party of the 1948 communist coup rented office space to the main publishing organ of the former capitalist oppressors. Each morning, as I arrived at work, I would pass below the “cherries” (the party’s symbol), offer the grizzled guy at the reception desk a mock communist salute (Honor to work!), stroll through the dilapidated courtyard and, if I had time, say good morning to a lonely-looking bust of the communist hero and Nazi resister, Julius Fučík, which stood in an isolated corner of the building’s second floor. To our hosts’ credit, though, the communists never interfered with our operations or tried in any way to influence what we reported or published. In fact, we had very little interaction with the rest of the building. To most of the comrades, we were simply the “crazy Americans.”

The offices, themselves, were threadbare and sad-looking, the sinks and toilets were dirty, but the space was large and adequate for what we needed. If there was any downside to the new location, it had less to do with the working conditions and more with our reputations. The Post’s ambitions, in those early days at least, went well beyond simply informing our English-language readers about political and economic events. We wanted to set an example of unbiased, Western-style reporting for our Czech readers to see. An important part of that effort was to avoid the appearance of any affiliation with a particular party or ideology. I’m reasonably certain no one ever mistakenly thought we were somehow aligned with the communists, but as more and more political parties emerged, and Czechs leaped to take opposing sides, we found it increasingly difficult to negotiate the country’s ever-widening ideological terrain.

The first big test of our objectivity came when the paper was just four days old, and like the rest of the country, the issue nearly ripped us apart. On October 4, 1991, Czechoslovakia’s parliament, the Federal Assembly, passed a controversial “lustration” law that was intended to prevent former communists, members of the secret police, and conscious collaborators from holding key posts in the government, education and judiciary for a period of five years. The law enjoyed broad support among the public and was widely viewed as a necessary step in preventing members of the old communist regime from abusing their former positions. At the same time, the bill raised serious legal and human-rights concerns and risked giving inordinate amounts of power to those groups and individuals who held the secret lists of possible collaborators. The mood was akin to a witch-hunt; a mere wisp that someone had cooperated with the secret police was enough to ruin his or her reputation. Klaus’s new Civic Democratic Party supported the law, while leaders of the more liberal and left-wing parties were opposed.

In a sense, I felt personally affected by the law after having worked so closely in the 1980s with (my Czech stringer) Arnold. By this time, it had been a couple of years since I last heard from him and I still wasn’t sure whether or not he had been a secret police informant (he was). I casually glanced through the leaked lists of suspected collaborators that appeared at the time to see if his name was among them. I remember feeling relieved when I didn’t immediately see it.

Despite our best intentions to remain objective, the Post was rapidly drawn into the center of the lustration controversy One of our own correspondents, a Czech parliamentary deputy named Jan Kavan, who wrote the paper’s weekly “Inside Parliament” column, stood accused by a government commission of being one of several deputies who had collaborated in the past with elements of the secret police. Kavan had spent decades living in the UK and was well-known at the time as the editor of a respected samizdat publisher, Palach Press. Though he strongly denied the allegations, he quickly emerged as one of the country’s most-divisive figures. (Kavan was later exonerated of the charges and went on to serve in both the Czech Senate and Chamber of Deputies. He also served as Czech foreign minister, from 1998-2002.)

The new law not only placed our correspondent in a difficult situation, but created a deep divide between the Post’s main editors, including myself, and the paper’s Editor-in-Chief, Alan Levy. We editors favored covering the lustration story straight down the middle and keeping the newspaper itself completely out of the controversy. Alan, on the other hand, wanted to use his prominent weekly “Prague Profile” column in the paper as a platform to defend Kavan and take a moral stand against the law’s perceived inequities. Amid vague threats on all sides to resign, Alan eventually got his way. In the column, which appeared in just the Post’s second edition, on October 8, 1991, Alan likened the law to something that could have come out of the former communist government itself, which never honored international norms like due process and “innocent until proven guilty.” Alan ended the column by saying that Kavan was a “correspondent who can be trusted.”

The profile was courageous, and Alan’s instincts in the end proved correct, but it was also reckless. In a society that was becoming more polarized by the day, Alan’s column angered readers who had supported the screening law. Many Czechs failed to notice the fine distinction between what had been Alan’s personal defense of a correspondent and the paper’s broader, more-balanced position with respect to the law itself. To this day, I remain torn. I had only interacted occasionally with Kavan myself and didn’t know him well. Like most of my colleagues, I found him to be aloof and moody. In fairness, though, we all sympathized with his plight.

A couple months later, I personally experienced some of the fallout from Alan’s column at a Christmas party held by Klaus’s Civic Democratic Party. When I had first started at the Post, I hoped to take advantage of my earlier professional contacts at Business International to report on stories that Prognosis couldn’t get and maybe even occasionally scoop the Czech press. Some of those contacts had by then joined Klaus’s party. I thought the Christmas bash might offer a chance to reconnect with those sources and perhaps even develop a professional relationship with Klaus himself. I admired the man at the time and hoped we might find common interests. I soon discovered the feeling wasn’t at all mutual.

At one point during the party, I spotted Klaus standing in the corner and decided to approach him. I offered him a handshake and introduced myself as The Prague Post’s business editor. I casually remarked that the paper would be interested in a sit-down interview if he could find the time. I wasn’t at all prepared for Klaus’s reaction. Instead of smiling or nodding, he squinted through cold eyes and grimaced. “Why would I ever talk to you?” he asked. “Everyone knows The Prague Post is a “left-wing newspaper.” I was taken aback and didn’t immediately think to ask why he believed that. Indeed, to this day, I’m not entirely sure, but it was very likely the result of Alan’s earlier passionate defense of Jan Kavan. Over the coming months, I and my colleagues at the paper would go on to develop contacts at Klaus's finance ministry and then later at the Prime Minister’s office (once Klaus became PM), but we never managed, after that, to establish a good working relationship with the man himself.

As of this writing, the paper’s original stories from the 1990s have not yet been fully digitized and remain unavailable through an internet search. That lamentable state of affairs may change soon. Click here to learn about efforts to scan and upload the paper's archives. In the meantime, print copies of all editions are available for researchers and public viewing at the Blue Owl Bohemia library in Loužnice, Czech Republic.

(Take me to Part Two).

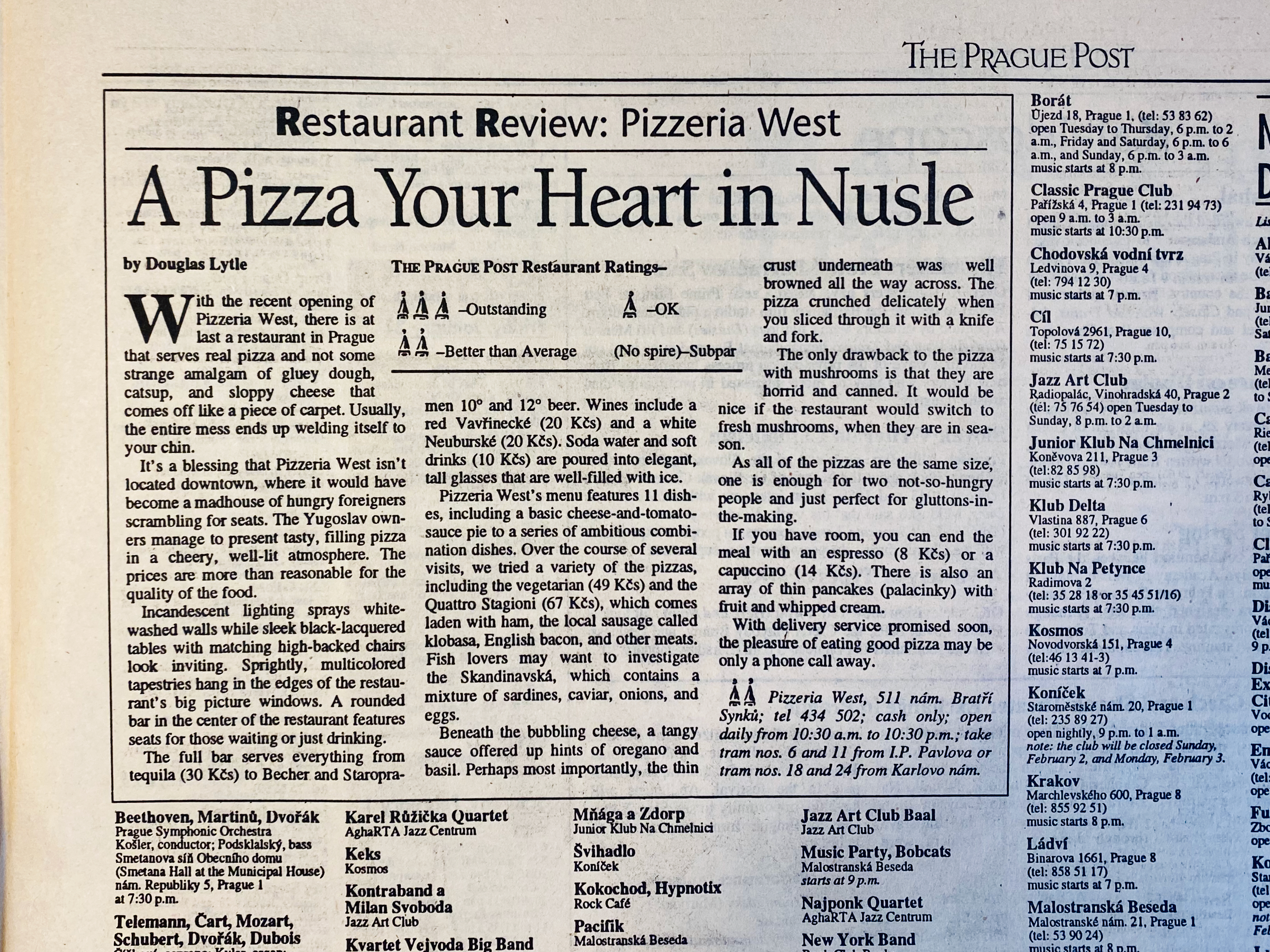

My old haunt in Nusle, Pizzeria West! And those prices. 🙂

Nice piece and looking forward to Part 2!

Yes, Pizzeria West marked one of the early great leaps in pizza quality!

Yes and still running strong.

Can’t wait for part II

Thanks Matt! The star of my book 🙂