The highlight of any trip to Czechia is the chance to see up close some exquisitely preserved examples of European architecture through the ages. A trip here is not unlike attending a university seminar on historic architecture – but with the chance to drink beer in class as well.

Thanks to the fact that Prague and the rest of the country were spared significant war damage over the centuries, visitors are treated to a nearly unbroken line of architectural development. The earliest surviving buildings, from the Romanesque period of around the turn of the first millennium, seamlessly give way to the grand 14th- and 15th-century Gothic structures of Prague, like Prague Castle or the Old Town Hall. Later centuries brought to Czech towns and cities the symmetrical, Italian-influenced Renaissance and the lavish, hypnotic baroque that was so favored by the Catholic Church and ruling Habsburg monarchy.

Czechia is also brimming with examples of those revivalist “neo” styles – such as “Neo-Renaissance” and “Neoclassical” -- that were all the rage in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 19th century. Fans of sumptuous, early-20th century Art Nouveau need look no further than Prague’s Municipal House to get their fix. Cities like Brno and Zlín were hotbeds of 1920s’ Functionalism and early-Modern. Brno’s ground-breaking Vila Tugendhat predicted – and predated by decades – the massively popular “Mid-century Modern” style that wouldn’t come to much of the rest of the world until the 1950s and ‘60s.

Yes, it must be admitted that people here definitely understand the value of historic architecture and the necessity to preserve old buildings – both for aesthetic reasons and for teaching future generations about the past. That is, however, until you get to the legacy of buildings that were designed and built during the communist period from the late-1940s to the 1980s. That’s where the consensus on preserving history starts to fray and opinions on aesthetics and teaching future generations start to get heated.

More than three decades since the fall of communism, Czech society remains deeply divided on the architectural legacy of communism. Some people want to fix up and preserve the buildings built during this period for practical reasons and as a symbol of the country’s recent history; others simply want to rip everything down and pretend that communism never happened.

What is ‘communist’ architecture?

Contrary to conventional wisdom – both here in Czechia and around the world – there’s no one style that defines "communist-era" architecture. Like architects in the West and the rest of the non-communist world, designers behind the Iron Curtain were constantly responding to changes in technology and the whims of fashion. It’s fair to say that by historical standards, many of these buildings lack any immediate aesthetic appeal (in fact, many are downright ugly). At the same time, the buildings have a lot to say about Czechia’s recent history and the times during which they were built.

A few years ago, the curators at Prague’s Museum of Decorative Arts (Uměleckoprůmyslové museum) staged an exhibition on communist architecture in a bid to educate the general population as to the value of preserving this legacy. The museum focused primarily on the massive communist-era, prefabricated housing estates that ring most large Czech cities – though the same styles they identified can be applied to other types of buildings as well. In presenting the exhibition, the curators pointed out that a third of all Czechs still lives in these types of public-housing estates. Many people have no choice but to accept and try to understand the architecture. There’s no option of pulling it all down.

The museum identified several distinct phases of communist-era architecture which can still be seen throughout Prague and rest of the country. The phases corresponded broadly to the different decades, from the communist coup of 1948 (that put the country firmly within the Soviet-led Eastern bloc) all the way to the Velvet Revolution of 1989. Visitors to Czechia are certain to impress their hosts by demonstrating at least some basic knowledge of the various styles. An offhand comment such as: "Wow, that looks like a classic example of 1970s’ Brutalism” is guaranteed to mark out anyone as a genuine expert.

Know your ‘Socialist-Realism’

The earliest examples of communist-era architecture, from late 1940s and 1950s, were built in the style of “Socialist-Realism,” which was imported directly from the Soviet Union. Socialist-Realist buildings tend to be grossly oversized and marked with mosaics and decorations that hewed to the ideological line at the time of glorifying workers and peasants. Anyone who’s been to Moscow will recall the massive Stalin-era skyscrapers there. One of the best-known Socialist-Realist buildings in Prague is the 1956 “Hotel International” in the outlying district of Dejvice, with its soaring towers, mosaics and impressive interiors. Olomouc’s “Astronomical Clock,” on the northern face of the Town Hall, built in 1955, provides a marked contrast to Prague’s much-older astronomical clock. Instead of a parade of figurines from the Middle Ages, as in Prague, Olomouc’s clock features a shockingly modern display of industrial workers and tradesmen.

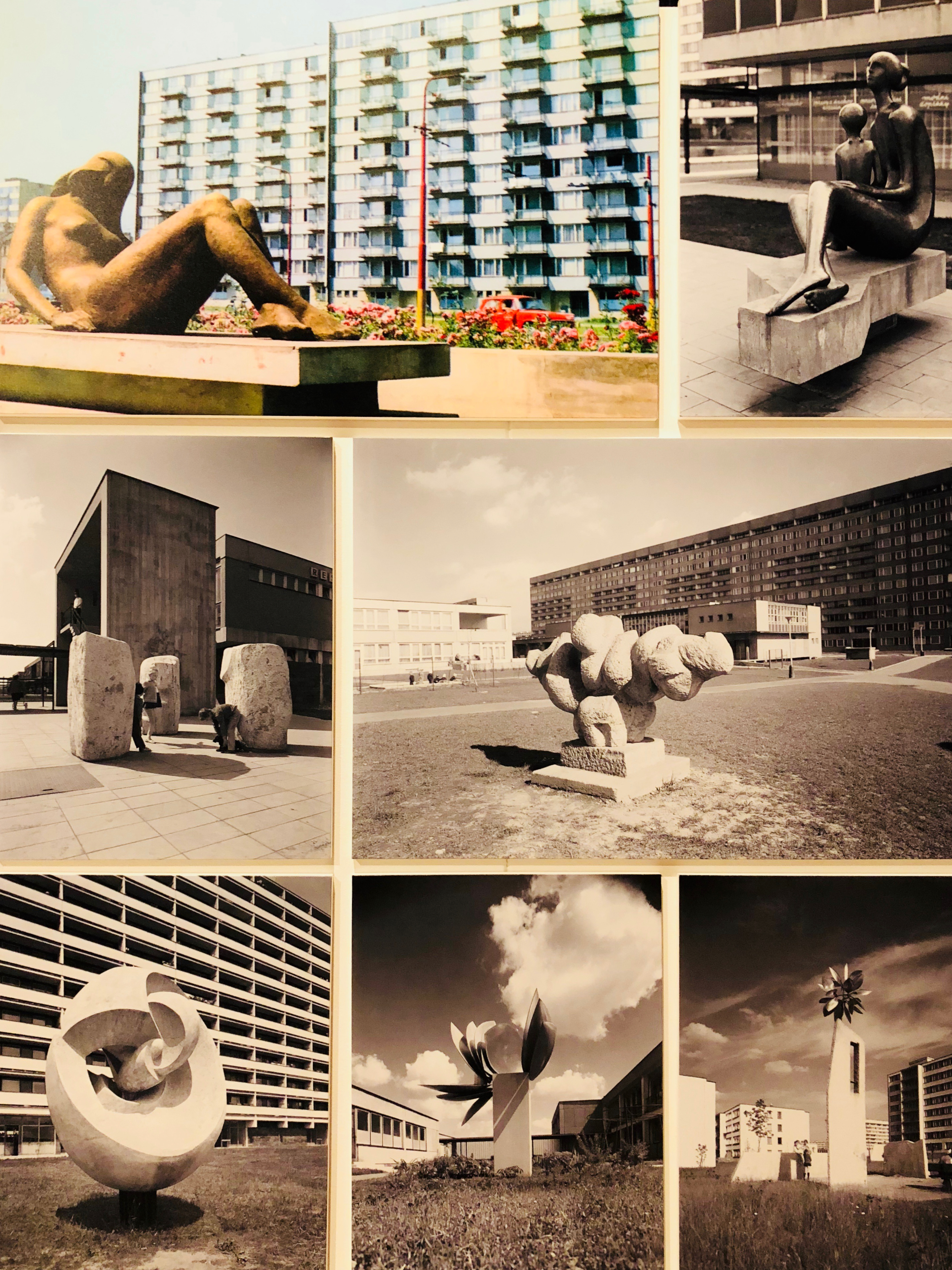

The decade of the 1960s saw the construction of the first massive, city-sized housing estates around the country. In many respects, these stripped down, high-rise blocks resembled the similar, often-depressing public-housing complexes one finds in the US, UK and many other countries. Czech architects, at the time, tried to soften the structures’ appearances by adding decorative statues, fountains and water pools to the exteriors and grounds. (Many of these decorative elements have been neglected over the years and are invariably in poor shape). Visitors to Prague can see a good example of one of these housing complexes by taking a quick metro ride out to the Invalidovna station (Line B).

In the 1970s, Czech architects took their cues from the West and crafted their own brand of communist-era “brutalism.” This architectural style – which takes its name from the French term for raw concrete (béton brut) – wasn’t just an Eastern bloc thing but was extremely popular around the world (Boston’s City Hall and London’s Barbican Centre are good examples). Czech brutalism is similar to its Western cousins in that the buildings typically reject external decorative elements and highlight instead less-aesthetically-pleasing aspects, such as the construction materials used to build it (often raw concrete or steel) or details like exposed pipes and ducts.

The conceptual idea behind brutalism was to reveal the buildings’ innards in order to make them more transparent. In reality, the buildings are hard to love. Britain’s King Charles III (then as Prince Charles) once famously labelled brutalist buildings as “carbuncles.”

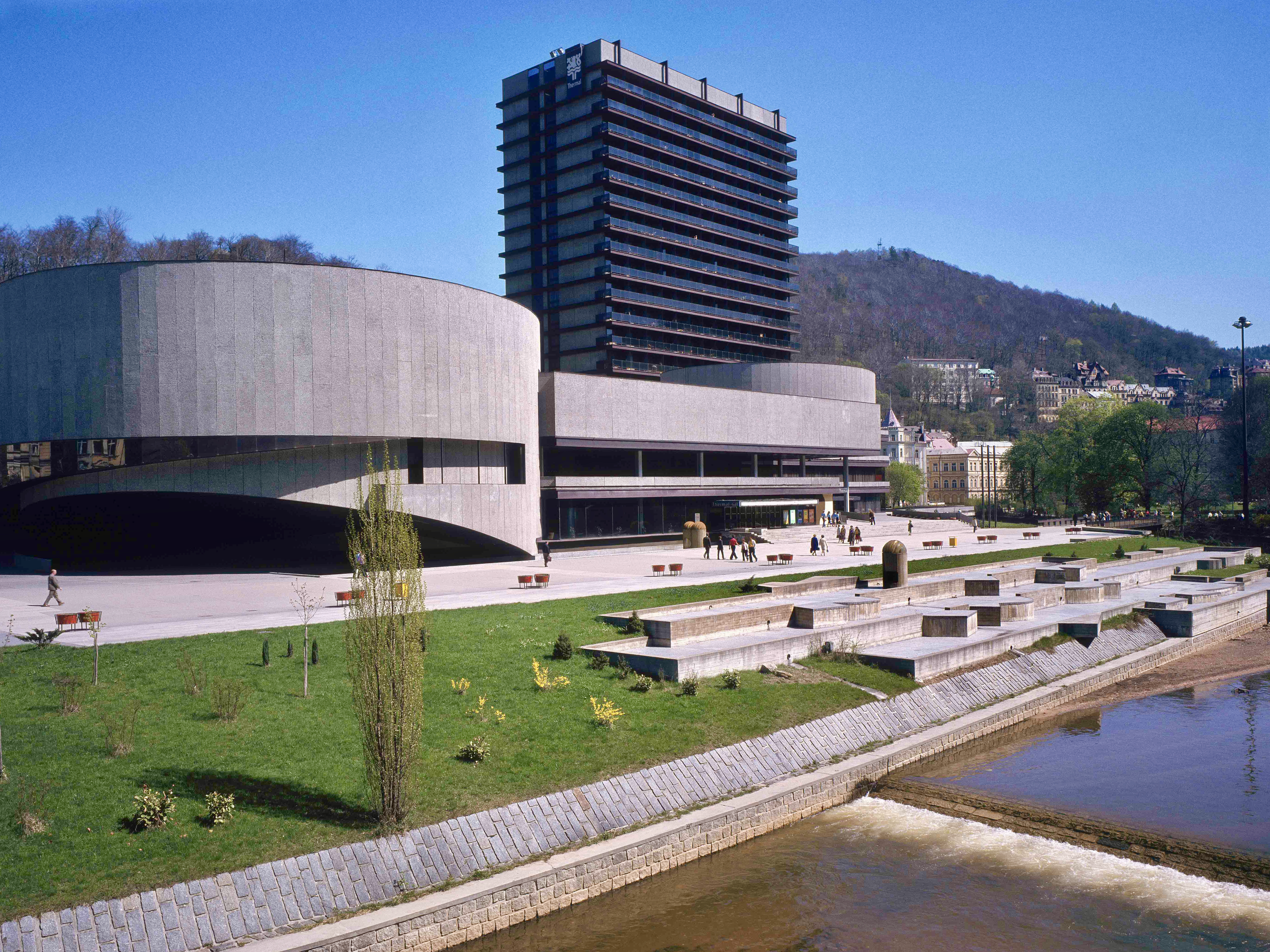

Czechia is filled with excellent examples of brutalism. In Prague alone, both the prominent Kotva and Máj (located at the corner of Národní and Spálená streets) department stores are examples of brutalism. Máj is said (charitably) to be modelled on Paris’s Centre Pompidou. The former Hotel Intercontinental in Prague’s Old Town is another brutalist gem (or eyesore, depending on your point of view). The Hotel Thermal, in Karlovy Vary, the host venue of the city’s international film festival, might very well be the country’s best-known brutalist building.

A war over memory

Like urban warfare, the battles over whether to preserve these buildings are often fought house-to-house. In 2019, the Kotva department store finally gained protected status from the Czech Ministry of Culture, ensuring that it cannot be knocked down. That same year, another similar, communist-era building in Prague, the brutalist Transgas complex in the neighborhood of Vinohrady, from 1978, was unceremoniously demolished as an eyesore. Last year, the brutalist Central Telecommunications Building in Prague’s Žižkov district was ripped down. Chemapol appears to be next on this list.

Czechia’s cultural officials say they take several factors into consideration when deciding on whether to grant a building protected status. These include things like how important or ground-breaking the structure was at the time it was built and how effectively it articulates a particular architectural style.

These considerations may well be true, but the real battle seems to have little to do with the quality of the buildings themselves, but rather the continual tug-of-war underway in society concerning the legacy of communism itself.

Some three decades after the fall of communism, a significant proportion of Czech society continues to see nothing at all redeeming about an authoritarian system that controlled their lives and limited their freedoms. For them, the buildings themselves are constant reminders of a corrupt and immoral system, and the various communist-era architectural styles are simply historical aberrations. Local architects designing today, according to this reasoning, would be much better off in adopting the best of contemporary international styles or turning the clock back to the last great Czech architectural iteration: functionalism from the 1920s and ‘30s.

On the other side of the coin, preservationists point out that fashions invariably change over time, and what one generation considers to be hideous can often be viewed by later generations as something beautiful (or at least interesting). After all, the baroque statues on the Charles Bridge were also once considered eyesores – the work of over-zealous Catholic overlords despoiling a dignified Gothic bridge. These days, of course, it’s exactly that tension between baroque and Gothic that gives the bridge its energy and beauty.

It’s impossible to predict which way the battle will go, but as of this writing, the arguments rage on.

Anthony Hennen wrote a very good piece about a similar fight going on in the Czech Republic, this one over the fate of communist-era statues and monuments. Find it here on this link to his substack (open): https://midcentury.substack.com/p/re-evaluating-communist-art-in-czechoslovakia?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=uwcc