Judging by the explanatory materials of the Museum of Decorative Arts' new exhibition on postwar public housing: "Residence: Prefab Estate" (Bydliště: panelové sídliště), the curators obviously knew they were stepping into a controversial subject: the Communist legacy concerning public housing.

From 1948 until the late-'80s, the Communist regime constructed millions of residential apartments in cities and towns around Czechoslovakia to help ease a post-World War II housing crisis that lasted until the fall of Communism in 1989. The majority of these apartments were built as massive, freestanding blocks of multiple units, stacked one on top of the other. The state-run building companies made copious (and often indiscriminate) use of industrialized construction techniques developed after World War II and relied heavily on prefab-concrete panels as the main material.

The prevailing local attitude the past couple of decades toward these buildings has not been overwhelmingly positive. While many people concede the beneficial role of these “panel estates” in helping people to obtain their own homes, many would also agree the overall experiment in mass construction has been something of a disaster. Not only do bland, cookie-cutter apartment blocks surround nearly every city in the country, but their institutional drabness has somehow seeped into the national psyche.

I don’t want to get too Margaret Mead here, but in addition to destroying historic towns and villages and despoiling the natural environment, these oversized housing projects have also homogenized the culture somewhat and stunted the national spirit.

Or maybe not?

And that’s where this exhibition steps in.

The organizers seem to view themselves as a kind of tonic: a corrective to balance out the mainly one-sided, negative narrative on Communist-era housing. Sure, these prefabricated housing estates have lots of critics, the organizers argue, but the reality is one in three Czechs still lives in this type of building (more than 20 years after the last one was built). And not only that, many residents are reinvesting in their panel apartments, ensuring the buildings remain a significant part of the urban landscape for decades to come.

In the words of the curators: “It's necessary to learn to live with our heritage of prefabricated housing ... We need to examine the architecture thoroughly to uncover its overlooked qualities, and also try to compensate for the deficiencies and weak points.”

The exhibition builds on the work of teams of researchers, who studied the most important prefab housing projects in the country. The researchers identified six distinct phases of prefab construction, each phase reflecting its own specific political and economic factors, as well as changes in building technologies.

So, what's the verdict?

I think the exhibition largely succeeds. While not all six phases are supported equally well, I learned a lot and will never look at these prefab buildings in quite the same way. I would never have guessed there might be a period historians would label the "Beautiful Phase" for these massive housing projects -- but beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, as they say.

But rather than describe the exhibition, I’ll simply note below the various periods and flesh them out with a few paragraphs:

Archaic Phase (1945-50)

The first period lasted from the end of World War II until about 1950. In the immediate aftermath of the war, architects attempted to resurrect some of the basic tenets of interwar Functionalism (clean design, smaller scale, modern materials), but the Communist coup of February 1948 interjected a dose of uncertainty into the model, and the period’s legacy is not strong.

Socialist-Realism (1948-54)

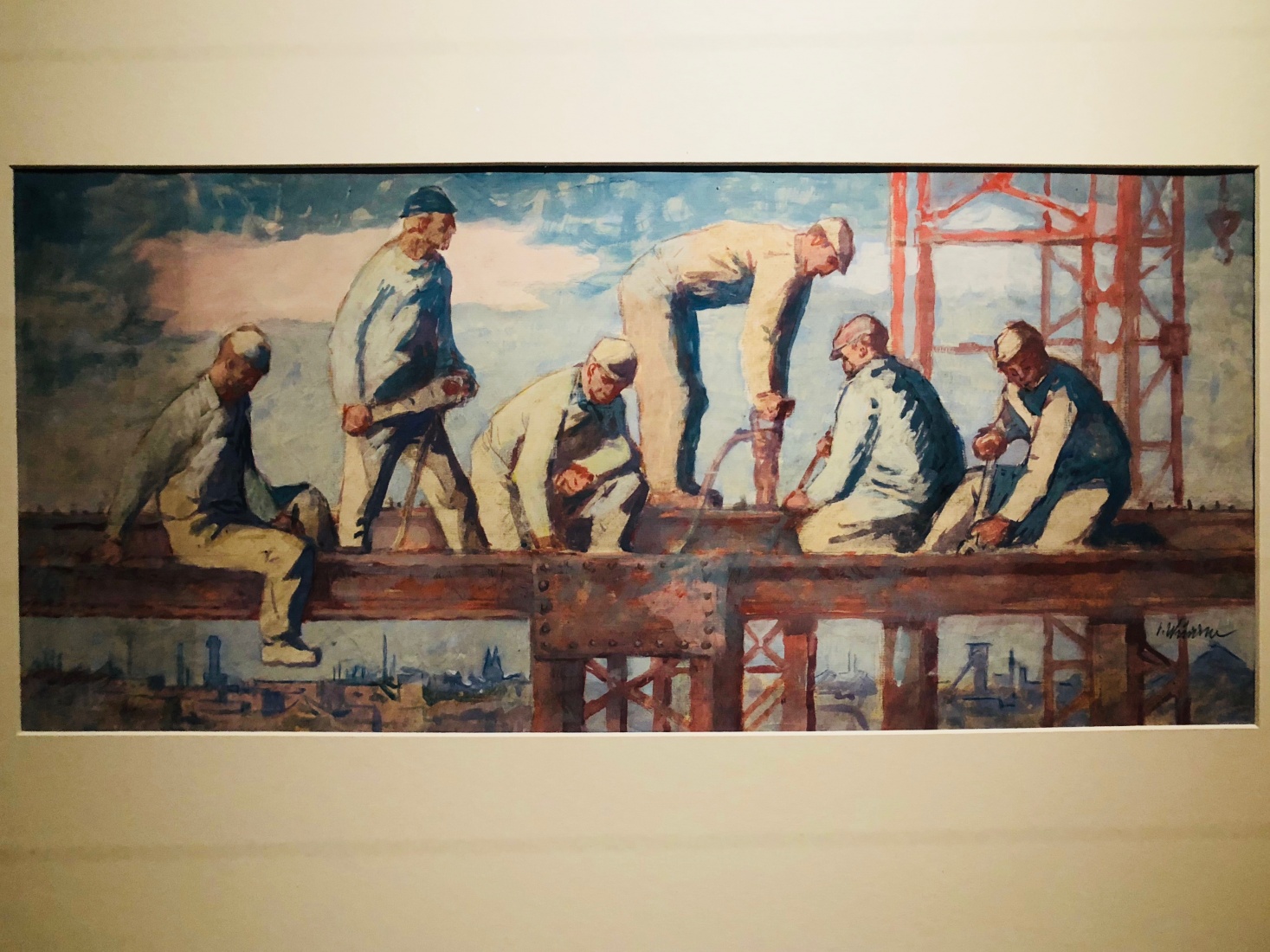

Starting from around 1950, architects came under heavy political pressure from the Soviet Union to follow the models and methods used in Moscow. As the exhibitors put it: local architects were required to announce their allegiance to the new “joyful” and monumental architecture of “Soviet Socialist-Realism.”

Socialist-Realism was a clear departure from interwar Functionalism, both in terms of the massive scale of the projects (see the photo of plans for the city of Ostrava) and in the use of external decorative elements, such as reliefs on building facades, to glorify the accomplishments of the workers in Communist society. The death of Stalin in 1953 and the uncertainty that followed ultimately put an end to this relatively short-lived movement and not many Socialist-Realism projects were ever built.

Pioneering Phase (1954-63)

The 1950s saw dramatic improvements in panel technology, and these were gradually incorporated into the country’s housing construction as the decade progressed. The exhibitors note that typical for this “pioneering phase” was the rejection of the decorative elements that characterized Socialist-Realism architecture: “in favor of a stricter and more exacting application of industrial technologies.”

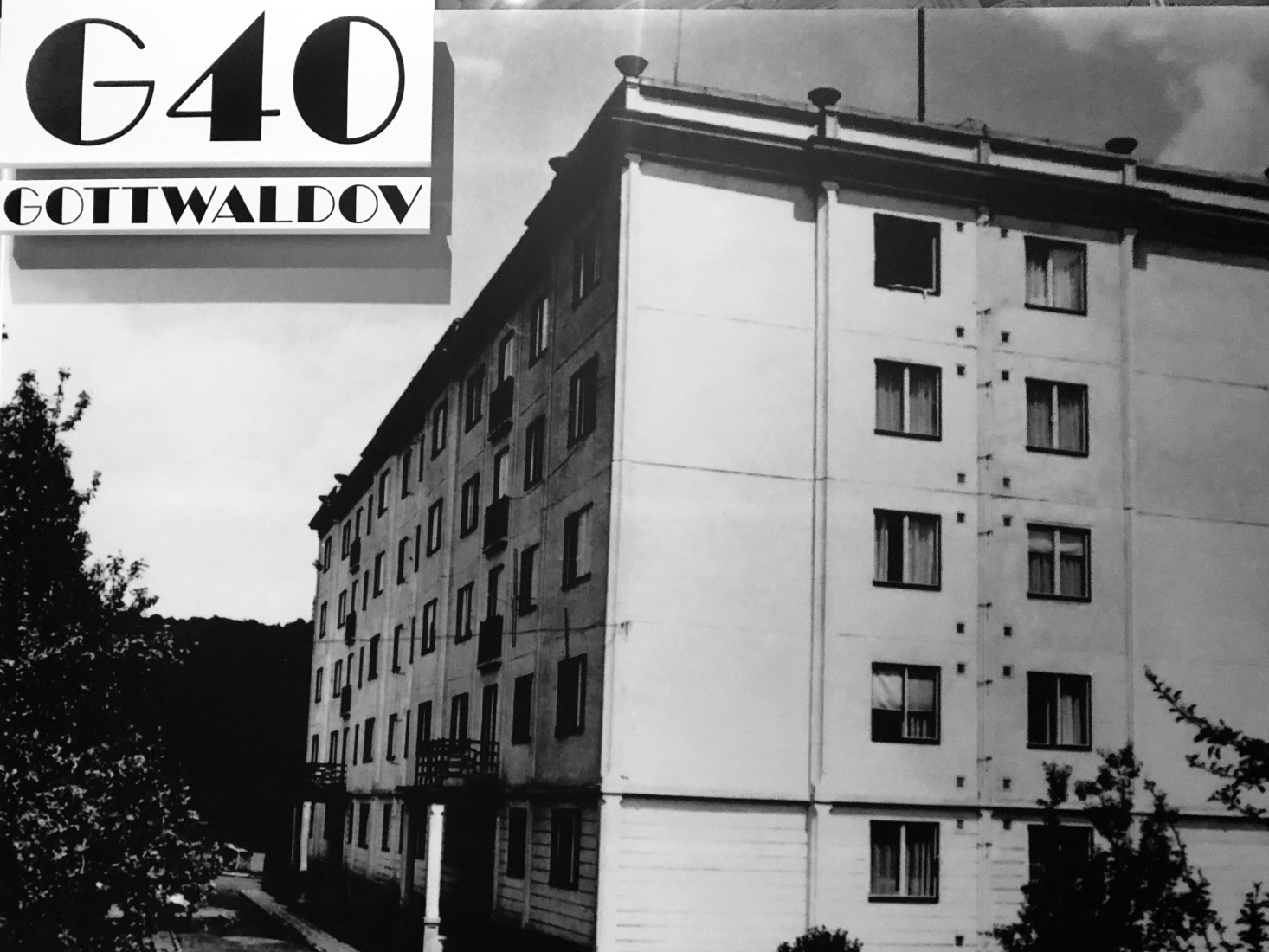

It was during this time, in 1954, the country’s first full-panel apartment block was completed, identified as type "G40." It wasn't built in Prague, though, but rather in the eastern city of Gottwaldov (now Zlín, see photo).

Now here's where the exhibition gets good (or jumps the shark, depending on your point of view):

Beautiful Phase (1960-70)

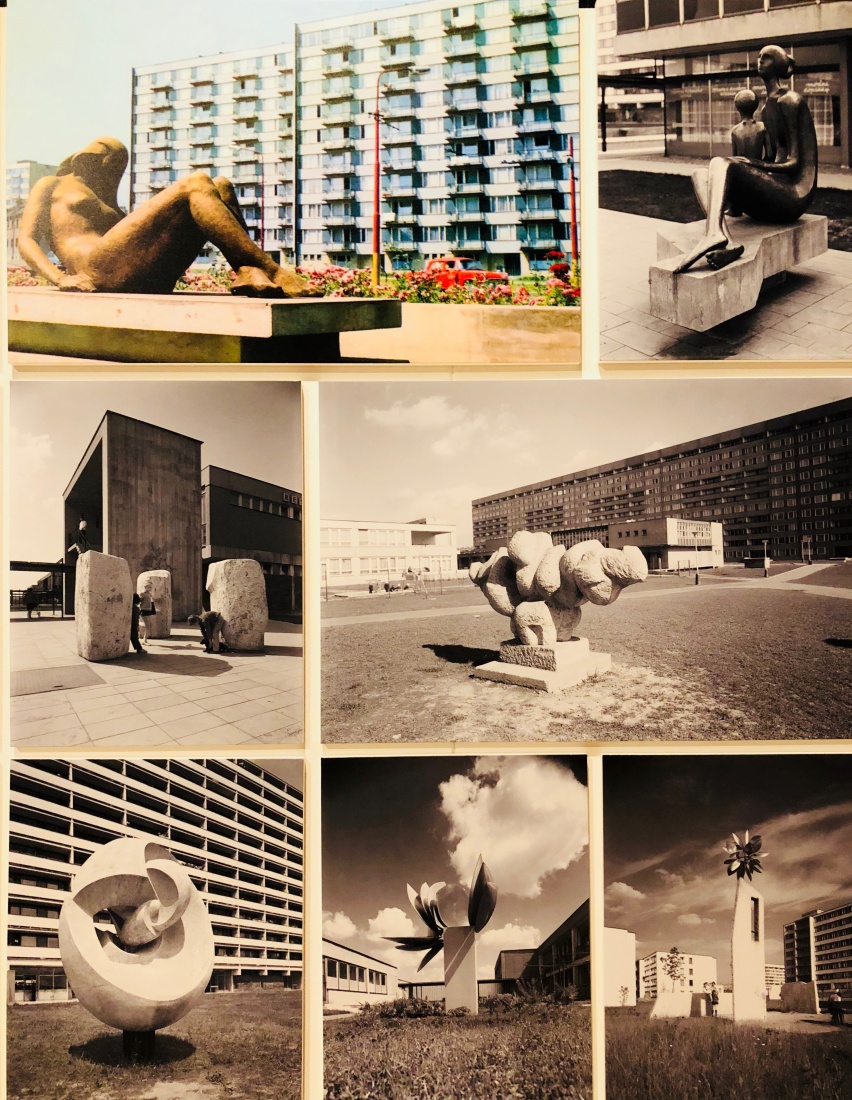

The 1960s, generally, are considered to have been a good decade for Czechoslovakia. Not only did the political system loosen up to allow for more open discussion, but architects felt freer to humanize the big blocks of residential apartments they were building. They did this by incorporating external decorative elements (fountains and sculptures) that softened the buildings' impact, and by adding shopping centers, schools, medical clinics, and other public services into the designs.

This is my favorite phase, by the way, and I’ve always been attracted to the futuristic, abstract sculptures and reliefs that dot many of these 1960s’ housing estates (and that are now often in such dreadful states of disrepair). For an example, see the photo here of the sculpture of a "blossom," by Jaroslav Vacek, from the Pankrác housing estate in Prague in 1971.

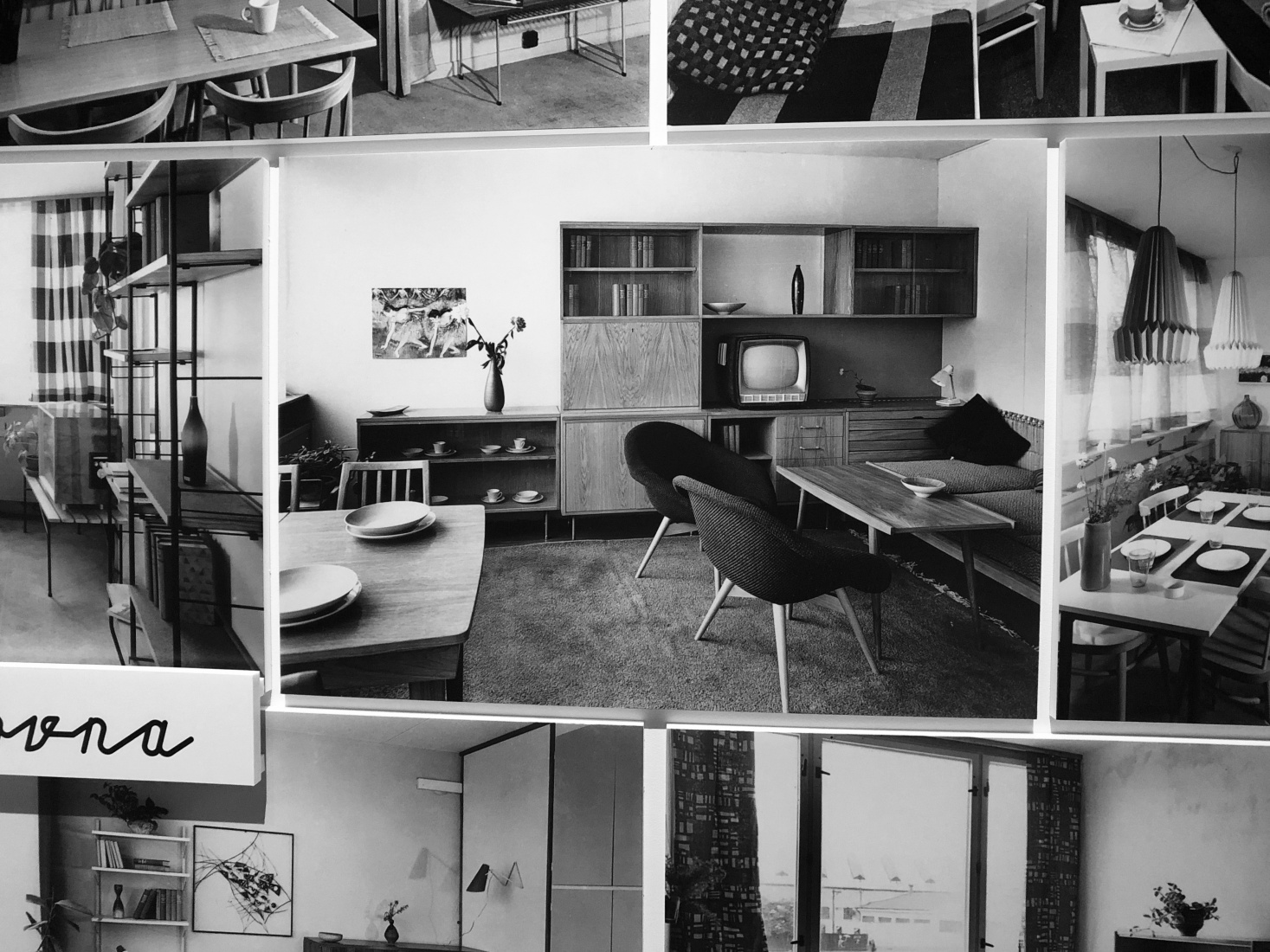

This part of the exhibition also features some nice examples of textiles and interior furnishings from the period -- and a porcelain set (see photo) from the Czechoslovak pavilion of the "Brussels ’58 World Fair," which inspired so many artists and sculptors of its day.

Technocratic Phase (1970-83)

The liberalism and openness that characterized the 1960s came to an end in the summer of 1968, with the Warsaw Pact invasion in August that year. Not only did the invasion put a dramatic end to the democratic experiments underway at the time, but it exposed supporters of the liberalization -- including scores of the country’s best planners and architects. Lots of these people were expelled from the Communist Party and lost their jobs. (In an earlier blog post, I write how my own Czech translator and fixer from the 1980s, "Arnold," lost his job and standing after 1968).

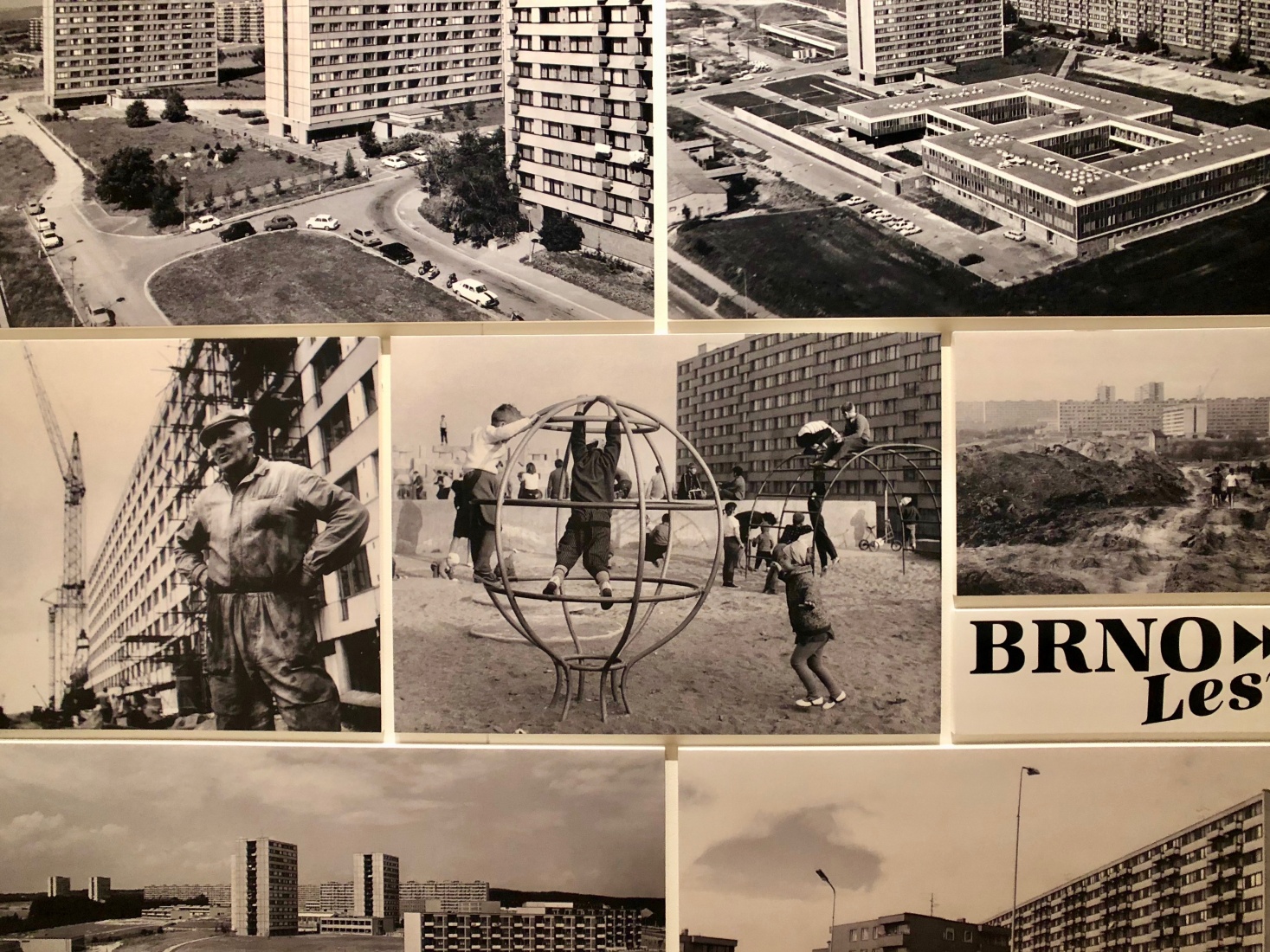

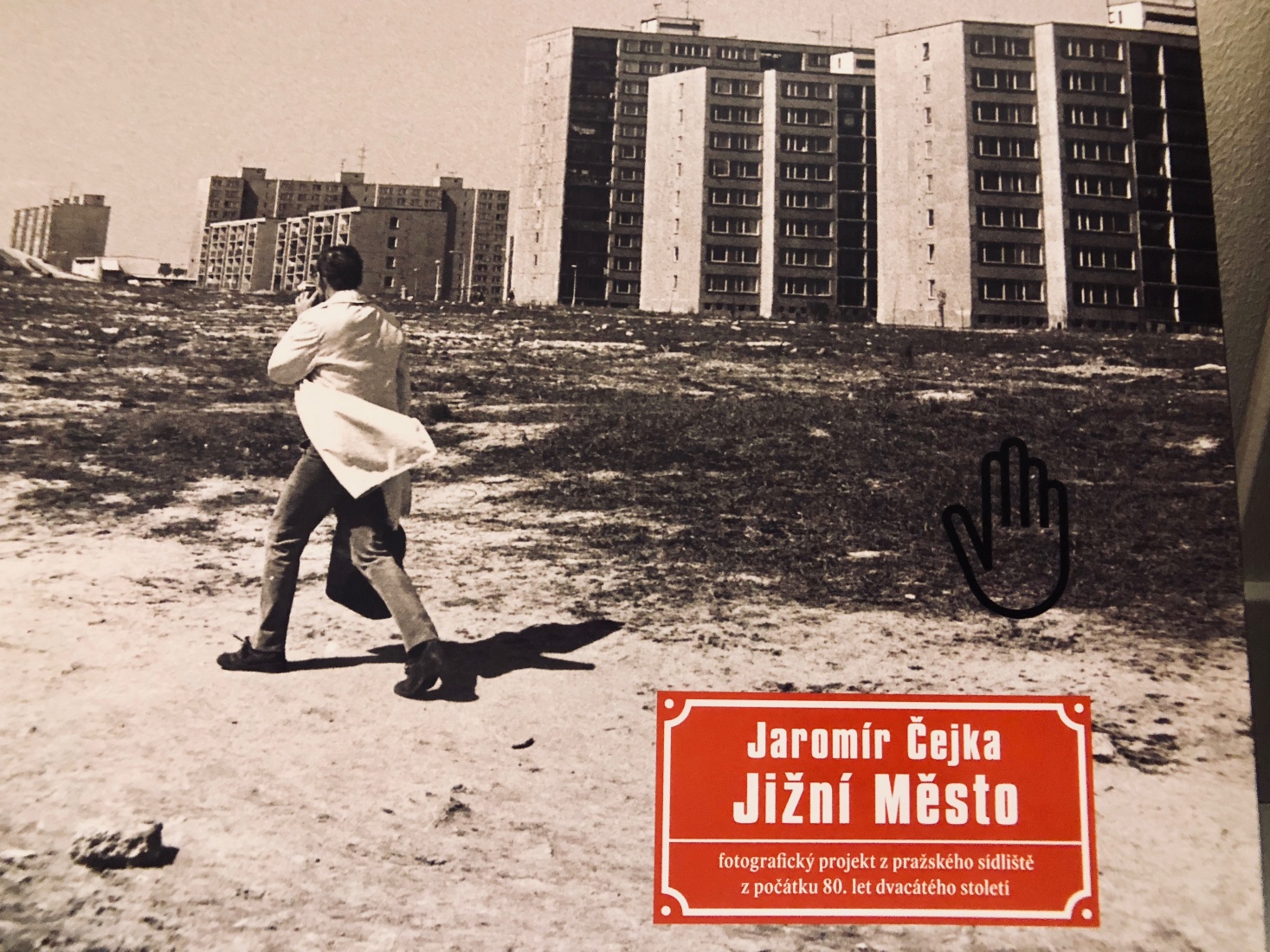

In the aftermath of the invasion, the decade of the 1970s saw big increases in investments in public housing, but with a decided emphasis on quantity over quality. It was during this time that many formerly green-field sites were transformed into massive, free-standing cities of their own, with populations, in many cases, exceeding 10,000 people. In terms of design, many of the same plans were replicated across the country, lending the projects a deadening sense of uniformity.

Prague’s “Jižní Město” (South City), the city’s biggest housing estate, with something like 90,000 people, was built at this time. To this day, it remains a national metaphor for the ills of public housing carried out on such a massive scale. It was the subject of Czech film director Věra Chytilová’s tragicomic film, “Panelstory,” from 1979.

Postmodern Phase (1983-89)

The curators identify a final phase of public-housing construction, which they term “postmodern,” though they don’t illustrate it very convincingly. Basically, the idea is that economic stagnation in the early-1980s led to a slowdown in housing construction. This allowed architects and planners to design on a smaller scale and incorporate older, more-traditional urban elements. I'm not sure I've ever seen a prefab housing project that exactly fits this description, but I'll take their word for it.

The exhibition runs to May 20. The Museum of Decorative Arts is located at ul 17. listopadu 2, in Prague's Old Town. The museum is open Tue-Sun from 10am to 6pm.

I understand the animus — especially in the destruction of older buildings to create the panelaks. (These tensions are at the center, for instance, of Vaclav Havel’s play Redevelopment.) A visit to the Jižní M?sto area in 1992 also gave me a sense of how anonymizing and alienating the surroundings might be on a larger scale.

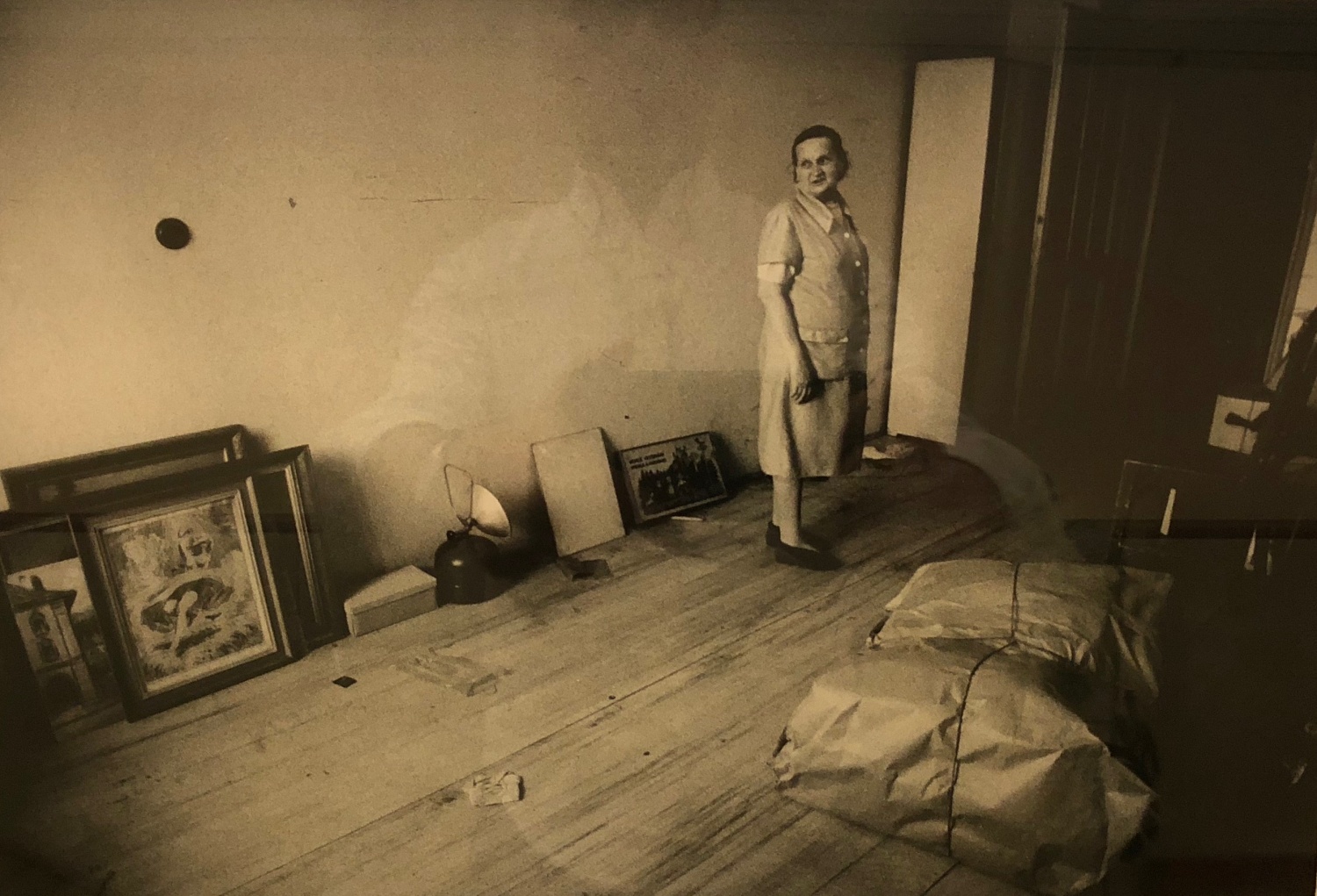

But as a resident of a panelak in my first year in (then) Czechoslovakia, I found the apartment itself to be better than anything I had lived in during my student and early young professional phase. Also, all the homes I entered that were located in panelaks were extraordinarily cozy and welcoming. That the exteriors could be grim and uninviting was understood, but behind each family’s door was a different and tidy world of their own creation.

This exhibit sounds marvelous. In adding nuance and complexity, it’s done its job.

Pingback: Panelák Housing in the Czech Republic and Slovakia | Tres Bohemes