I first came across “My Life as a Spy” by accident. In January 2022, a friend posted to her Facebook page a link to an episode of the “Invisibilia” podcast, titled “International Friend of Mystery.” The theme was “friendship,” and in this particular episode, an American anthropologist who had spent time in Romania (Verdery) recounted the dread she felt at discovering and reading her secret police files and finding out that many of her closest friends had informed on her without her knowledge. My own FB friend had no idea how timely that episode would feel to me. I quickly devoured the podcast episode and then downloaded Verdery’s book to my Kindle.

Because I was so keenly interested in the subject matter, I finished the book practically in one sitting, though it’s not a particularly easy read. Verdery’s book lacks something of the polish of, say, Timothy Garton Ash’s similarly themed “The File,” in which Garton Ash retraces the meticulous notes the Stasi assembled on him when he was a student in East Germany in the 1970s.

As a trained anthropologist, Verdery’s account, instead, is much more academic. She approaches the subject of her surveillance with the kind of rigorous discipline she might employ in her own field research. She’s clearly impressed by the painstaking detail the Securitate collected on her and the great lengths they went to in order to craft a credible espionage narrative around her activities in the country as the mysterious “VERA,” one of the spooky code names they gave her. The irony is by no means lost on her that while she originally came to Romania to study its people and culture, in effect, she became the object of their intense scrutiny and study.

“My Life as a Spy” is divided into four chapters, split in the middle by what Verdery calls an “excursus” on what it feels like to read one’s own file. The first two chapters are background material on why she came to Romania in the 1970s and ‘80s and introduces us to the main characters in her life from that time. Many of these people, of course, will resurface later in the book as informants. In the final two chapters, which make for some uncomfortable reading, Verdery confronts many of the people who spied on her – both the individuals who worked directly for the Securitate as well as friends and colleagues who “merely” informed on her for whatever reason.

Verdery first arrived in Romania in September 1973 as a young researcher to study the cultural history of a group of villages scattered in the west of the country, near the city of Deva – a region shared over the centuries by communities of ethnic-Romanians, -Germans and -Hungarians. (I know the area well from my own experiences as a guidebook writer). On one of her first days in the region, she inadvertently drives her "Mobra" motorbike (see photo) into a restricted – but poorly marked -- military zone. That innocent mistake, coupled with the fact that she’s a U.S. citizen, puts her squarely on the Securitate’s radar screen and serves as the starting point for everything that comes later.

On subsequent trips in the late ‘70s and 1980s, she returns to the area and relocates for a time to the regional capital of Cluj, with its large and suspicious (at least in the eyes of the Securitate) Hungarian minority. Because of her contacts with Hungarian academics and the fact that her surname ends in “y,” as do some common Hungarian names like “Nagy,” she is falsely suspected by the secret police of hiding her “Hungarian roots” and of therefore somehow being “anti-Romanian.”

At this point, “My Life as a Spy” takes a comical turn that appears to come directly out of Milan Kundera’s novel, “The Joke.” In that book, Kundera’s main character, a university student named Ludvík, jokingly sends his girlfriend – at the time an inspired young Marxist -- a tongue-in-cheek postcard with the words: "Optimism is the opium of mankind! A healthy spirit stinks of stupidity! Long live Trotsky!” Ludvík’s “joke” goes horribly awry among the more ideologically-minded comrades and marks a major turning point in the character’s destiny.

Similarly, Verdery, in her first book on the Transylvanian peasantry, tries and fails to use humor in a way that indelibly marks her in the eyes of her minders as somehow suspect. She recounts an old joke from the region in the 19th century involving an ethnic-Hungarian, -German and -Romanian. Her point is to demonstrate, in an easy-to-understand way, how stubbornly persistent ethnic stereotypes can be over time. The joke portrays the Hungarian as stupidly hot-headed, the German as cheap and scheming, and the Romanian as crafty yet underhanded (stereotypes that to some degree endure to this day). While members of all three ethnic groups might well have enjoyed a good laugh at their own expense behind closed doors, Verdery’s less-than-flattering public portrayal of the ethnic-Romanian served to reinforce suspicions she didn’t have the country’s best interests at heart.

Later in the 1980s, toward the end of the Ceaușescu dictatorship, Verdery spends time in Bucharest and associates casually with known dissidents. These types of contacts were common and she was certainly not involved in any deeply secretive espionage operation. For the Securitate, though, the interactions put the final nail in the coffin. Judging from the reports, they could never quite figure out if Verdery was hunting military secrets, stirring up restless Hungarian nationalists, destroying Romania’s image abroad or actively supporting the anticommunist opposition, but it didn’t matter. She was obviously up to no good.

As I was reading “My Life as a Spy,” I was acutely aware both of the ways in which our experiences were similar and also how they differed. Verdery’s trips to Romania, for example, were much longer than mine to Prague and other places in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s. She often stayed in-country for months at a time, while my longest stay in Czechoslovakia was just one month, in August 1988, to attend a Czech-language course in Brno. Consequently, she gave the Securitate many more opportunities to surveil her than I ever did the StB. Her file – at 2,781 pages – is probably much larger and more detailed than mine (I say “probably” here only because some of my own file was destroyed and I’m not sure how long it was -- though certainly it was much shorter).

Verdery also developed more personal connections and friendships in Romania than I did in Czechoslovakia. My main point of contact was my Czech translator and fixer, Arnold, whom I later learned was a paid StB informant (and wrote about here). Aside from him, I didn’t know many other people and made only a few loose friendships. That means, in practice, I can’t fully share in Verdery’s deepest (and most-painful) feelings associated with being surveilled by friends. As far as I know (as of this writing, I’m still sorting through the names of my informants), I was never deceived by anyone whom I considered to be close.

One final distinction might be that the Securitate, at least at times, actually did consider Verdery to be an active American agent. To the best of my knowledge, the Czechoslovaks were never sure about me. According to a paper in my file, the StB once queried their colleagues at the Soviet KGB to ask whether the publishing company I worked for in the 1980s, Business International, was in any way connected to American intelligence (spoiler alert: it was not). I couldn’t find an answer to that request. My best guess is that while they regarded it as a distinct possibility, they simply didn’t know.

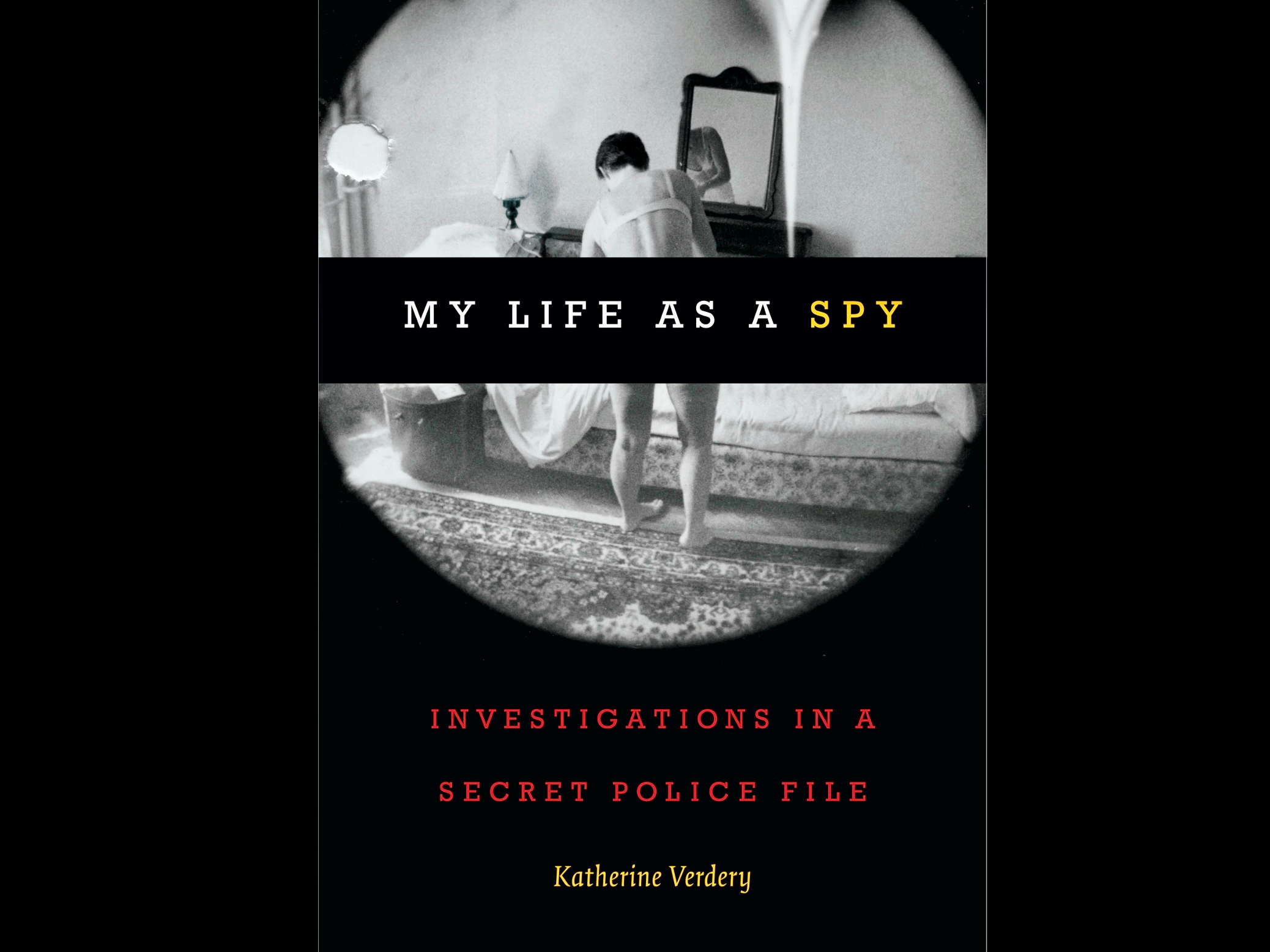

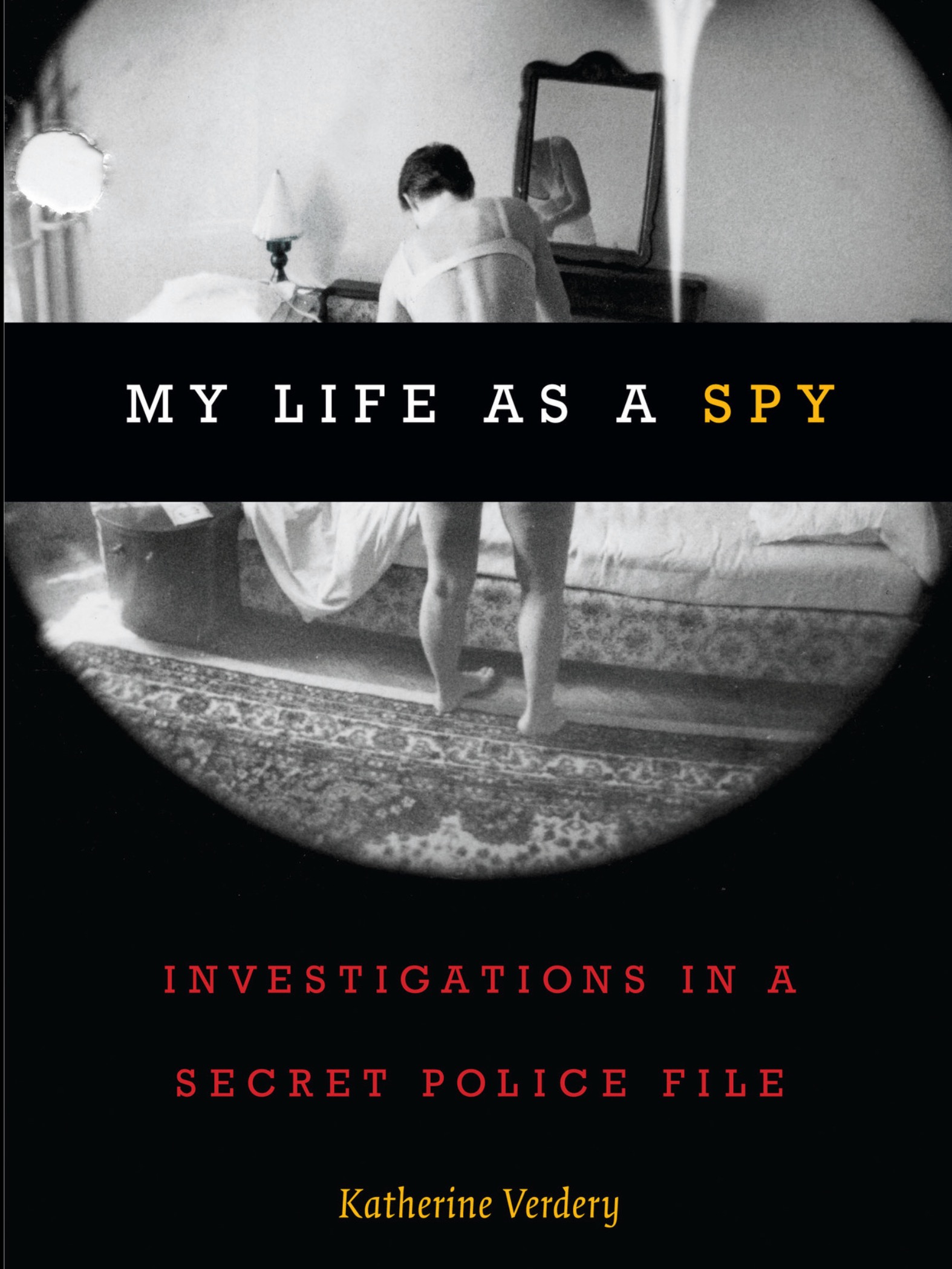

As a consequence, Verdery was subjected to much more intrusive forms of scrutiny than I was. Her phones were routinely tapped and monitored, her notes were stolen and copied and – in the most egregious example of all – the Securitate actually installed a permanent camera in her hotel room in Cluj in 1985 for long-term video monitoring. The photo on the cover of her book (printed at the top of this post) shows the author, dressed only in her underwear, bending over in her room at Cluj’s "Continental" hotel. I greatly admire the courage it must have taken her, not just to write this book, but also to illustrate it with such a deeply personal photograph that clearly conveys – for everyone to see -- the (needless) indignities they subjected her to.

The part of Verdery’s book I could most easily identify with (and learn from) was the emotional roller-coaster ride the whole process sent her on. While she admirably tries to stay even-handed in her analysis as she ponders the big questions of how the Securitate mistakenly came to see her as an agent and what motivated people to inform on her, it’s clear from the text that she’s also cycling through some now-familiar feelings.

These include, of course, shame and embarrassment for having been so naïve (she was aware, as was I, that the secret police would be watching, but just not to the extent that they did), as well as plenty of justifiable anger and indignation for having been so closely monitored and observed. There’s lots of comic relief as well in seeing just how poorly written and inaccurate the reports were, and in learning of the fantasies that the regimes had to conjure up in order to sustain their fictional espionage narratives. (I'll have more on this in my case in future posts.)

These more viscerally satisfying emotions, like anger and laughter, are inevitably moderated by twinges of guilt for having placed local friends and colleagues in such difficult situations in the first place. Perhaps, she (and I) should have been better aware of the obligations and pressures that our mere presence as "Westerners" imposed on those with whom we came into contact. At the extreme end, this guilt reaction risks sliding into a form of “Stockholm Syndrome,” where we begin to buy wholesale into the rationalizations offered up by the secret police officers, former friends and informants that “it was a different time,” “the system was evil,” and “we were just doing what we had to do.”

Verdery understands very well the nuances here and ably tries to strike a balance in all this (and there’s a lot more to her book that I wasn’t able to address here). “My Life as a Spy” shows, though, the power these files still wield - and the pain they can still inflict - in the absence of any easy explanations.

(In March 2023, I began publishing stories from my own surveillance file. Click here to go directly to the first of those stories. MB)

After writing up my thoughts on Katherine Verdery’s excellent book, “My Life as a Spy,” about her time in Romania in the 1970s and ‘80s and being surveilled by the Securitate, I emailed her a link to the story. I was very happy to receive this response:

“Thanks so much for sending this, and for a discerning read! Your own story sounds exciting too, so please let me know how to access future installments.”

Best, Katherine