Every kid probably goes through an astronomy phase at some point growing up. My own phase came when I was 12, just after my parents moved to a new house and both my brother (a year younger than me) and I were starting at a new school. The public schools in our new neighborhood were not very good, so my parents sent us to the local Catholic school (though neither of us were Catholic). The adjustment wasn’t easy.

In retrospect, I suppose it was natural for me to dive into an interest that would let me leave my earth-bound troubles behind, at least temporarily, and contemplate the heavens. I don't think my brother shared my passion for astronomy, though he had much better handwriting than I did back then. The two of us linked our talents together, one day, and attempted to write a book on all 88 constellations in the sky.

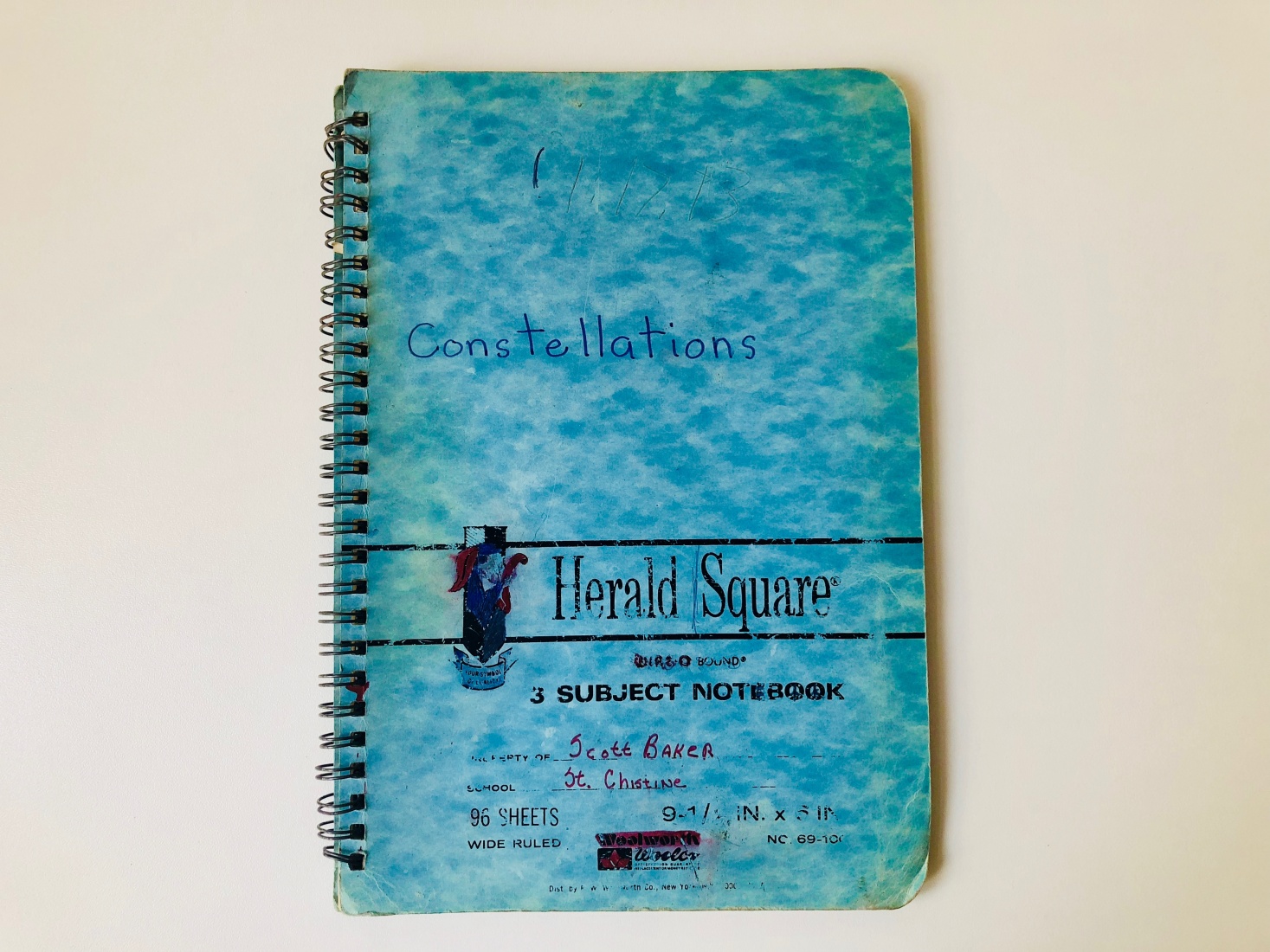

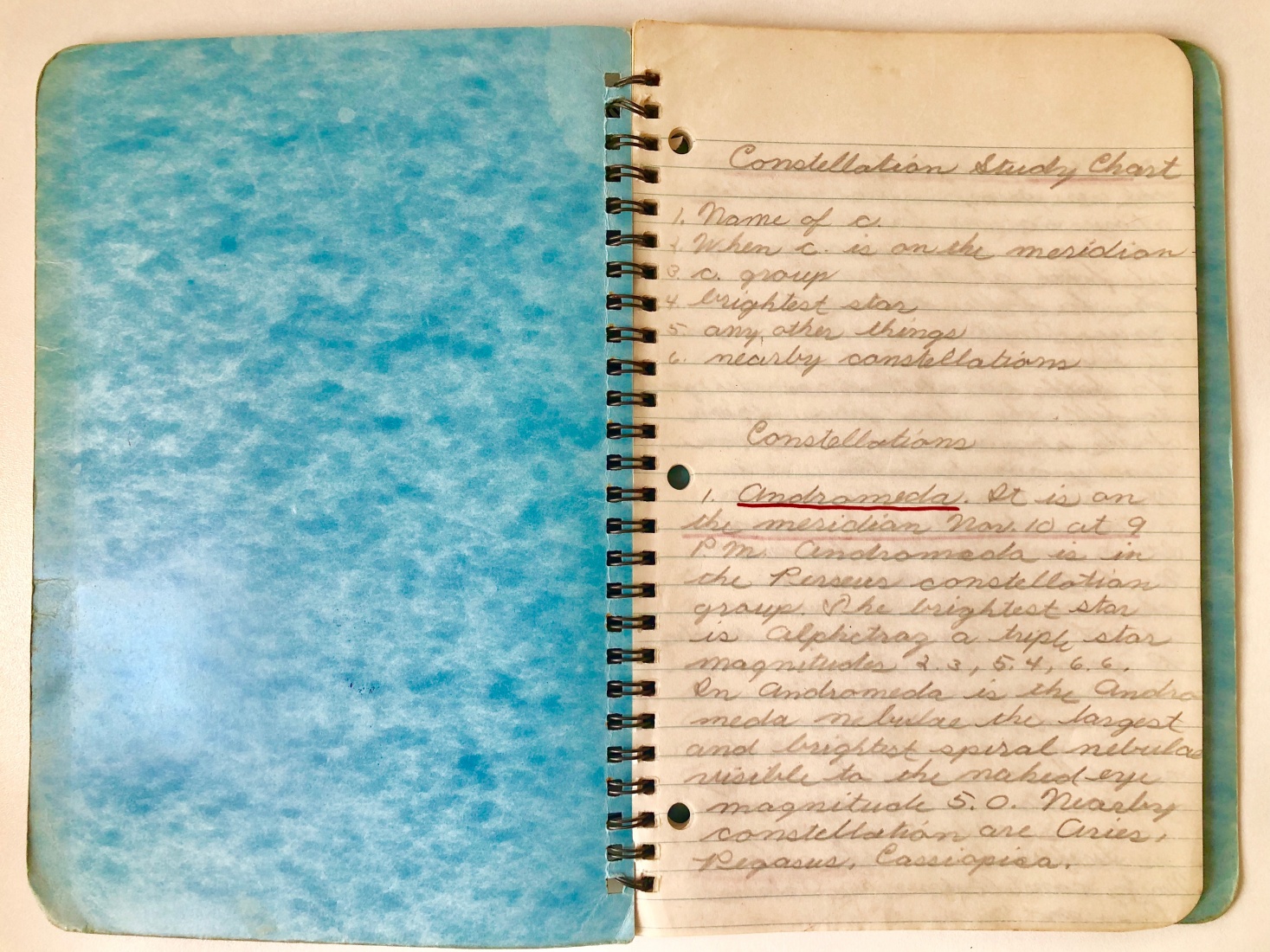

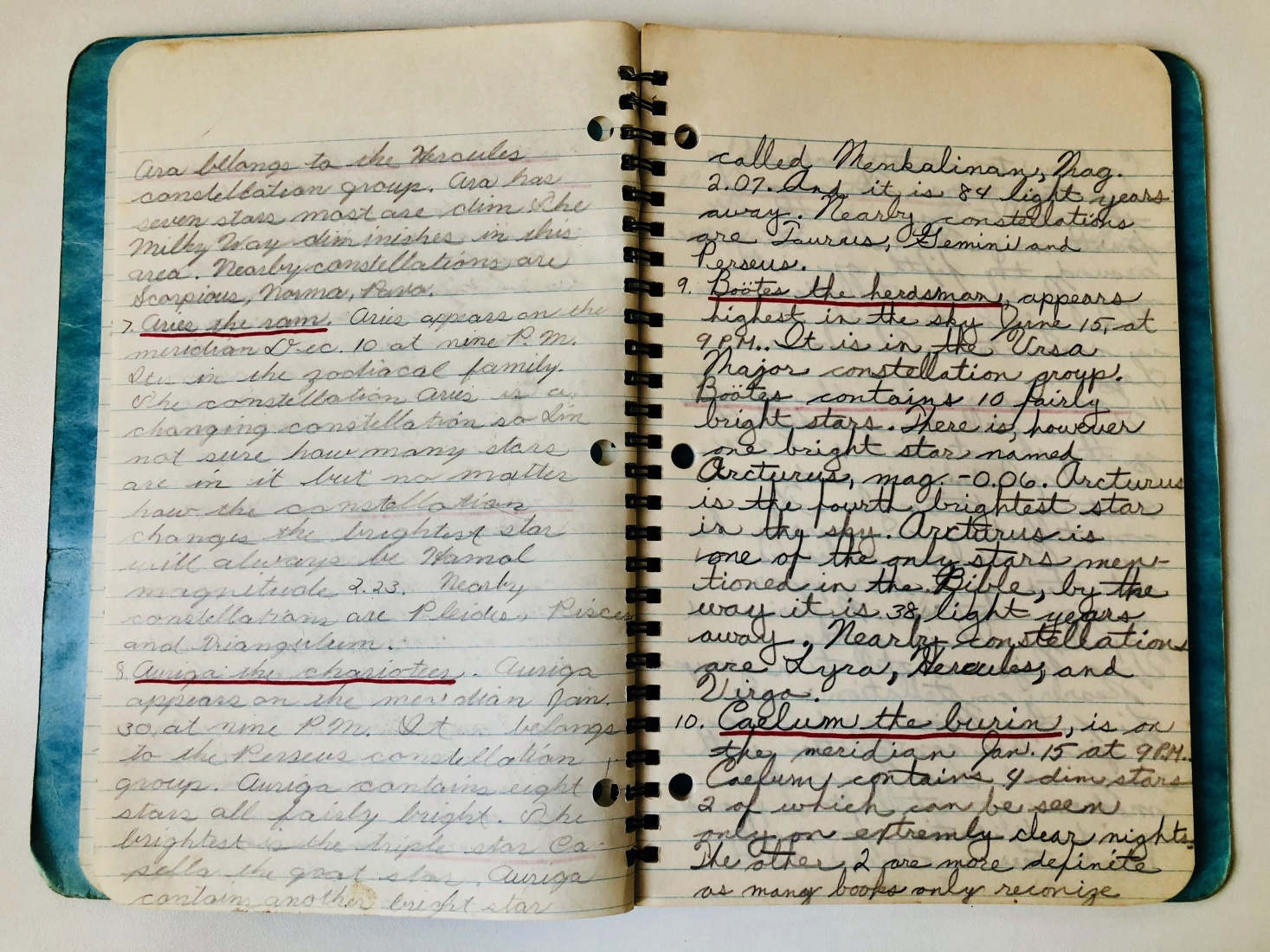

I recently pulled out our old notebook and looked over the surviving scraps of manuscript (see photos). As I remember the process, I would dictate the contents and my brother would write it all down. (He might remember the process differently – maybe he was the "genius" and I was the scribe?) We were methodical in our approach, describing each constellation, marking the date and time they appeared on the meridian, their brightest stars, and anything else worthy of note.

In paging through our old notebook, though, I realized we didn’t get very far. We'd arranged the constellations alphabetically, and the notebook abruptly ends somewhere in the “C’s,” at Cassiopeia. I suppose my brother and I moved onto something else. We both became interested in collecting 8mm movies around then.

Even though we never finished the book, my layman’s interest in astronomy has served me well over the years. It’s not difficult to memorize the appearance of the planets and positions of the brightest stars, though it’s surprising how few people make the effort. One of my favorite games on a summer evening is to ask people what their horoscope is and secretly hope they say Gemini, Leo, Taurus or Virgo – all easily visible in the northern hemisphere at that time of year. Lots of people have never seen their own astrological signs, and they usually seem amazed to find out they really exist.

All that’s to say I was thrilled when I moved to Prague and learned about the role that astronomy has played here over the centuries. I was particularly surprised to discover that Albert Einstein (1879-1955) had spent time here as a young professor. (I realize Einstein isn’t, strictly speaking, an astronomer, but his observations and theories have profound consequences for our understanding of the heavens.)

Einstein arrived in Prague in 1911, with his wife and two sons in tow, to accept a position as professor of mechanics and physics at Prague’s German University. They stayed for 16 months. The appointment came just a few years after the publication of one of Einstein’s early papers on general relativity, in 1905, and he was already gaining celebrity status by then.

Much has been made of his residence here, particularly whether or not he had a friendship with the Prague writer Franz Kafka. It’s clear from writings at the time that the two men traveled in similar circles (German-Jewish Prague) and knew of each other, but there’s not much evidence to support the fact they had a close friendship (even though that would awesome to contemplate).

Einstein’s time in Prague proved fruitful for his later work on relativity, particularly for his groundbreaking book "On the Special and General Theory of Relativity," in 1916. The Albert Einstein website points out that in the book’s preface, Einstein singled out his time in Prague for helping him to work out some of the stickier details of relativity. These included the notion that the refraction of light from the sun could be measured, and some minutiae pertaining to the gravitational red shift of spectral lines (way too complicated to get into here, even if I did understand it).

Einstein’s Serbian-born wife, Mileva Marić, a talented physicist in her own right, apparently didn’t like Prague as much as Albert did. When the opportunity arose, in 1912, to transfer to a teaching post in Zürich, Einstein accepted, and he and the family said goodbye to the “City of a Hundred Spires” for good.

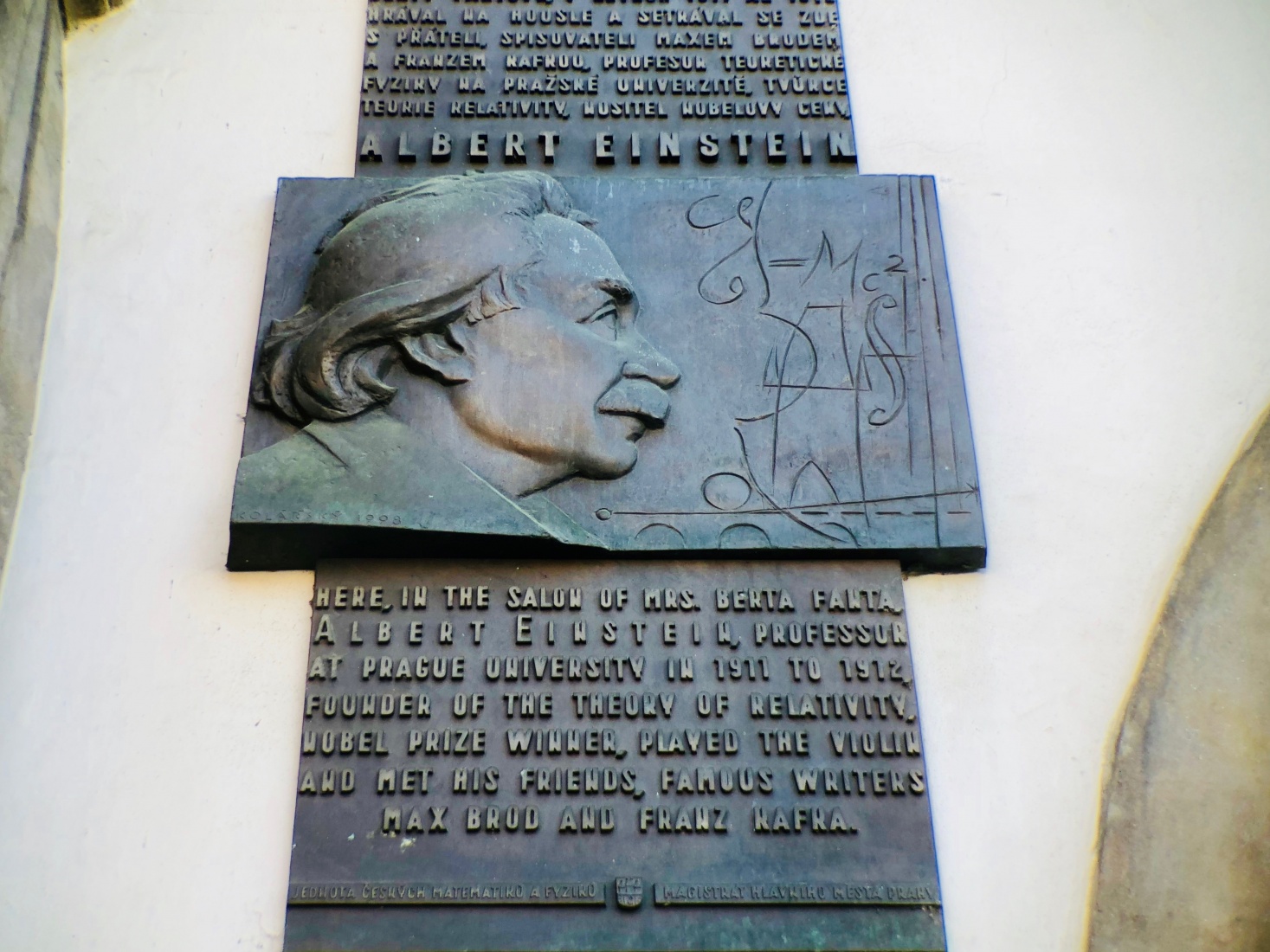

As Einstein’s time in Prague goes back only around a century or so, there are still lots of surviving traces around town. During his Prague stay, Einstein lived in a comfortable, middle-class apartment at Lesnická 7 in the district of Smíchov (see map plot, below). My own favorite Einstein memorial can be found on Old Town Square at Staroměstské náměstí 17, the former home of the socialite Berta Fanta. She ran a weekly salon in her drawing room that must have been the talk of the town. The memorial plaque reads:

“Here in this salon of Mrs. Berta Fanta, Albert Einstein, professor at Prague University in 1911 to 1912, founder of the theory of relativity, Nobel prize winner, played the violin and met his friends, famous writers, Max Brod and Franz Kafka.”

That never fails to wow me when I’m downtown and happen to see it.

The last astronomical luminary, Christian Doppler (1803-53), appears to have left the least significant mark on Prague of the four, though oddly rivals Einstein as perhaps the most famous name of all. Where would “Doppler Radar Weather” – so prominent on local TV newscasts in the United States – be without the man who first recognized the “Doppler Effect” that made it all possible?

From what I remember of the Doppler Effect from high school, it can be summarized like this: the measure of a wave’s frequency depends on both the speed of the observer and the speed of what he or she is measuring. It can be applied to both sound and light waves. With sound, you actually hear the Doppler Effect in the change of pitch as a police or ambulance siren approaches and then moves away. With light, it can be seen with stars and other celestial objects to determine whether they are moving toward or away from us, and at what speed. (I’m not sure exactly how it works with television weather.)

Doppler based his own findings on studying the properties of binary stars.

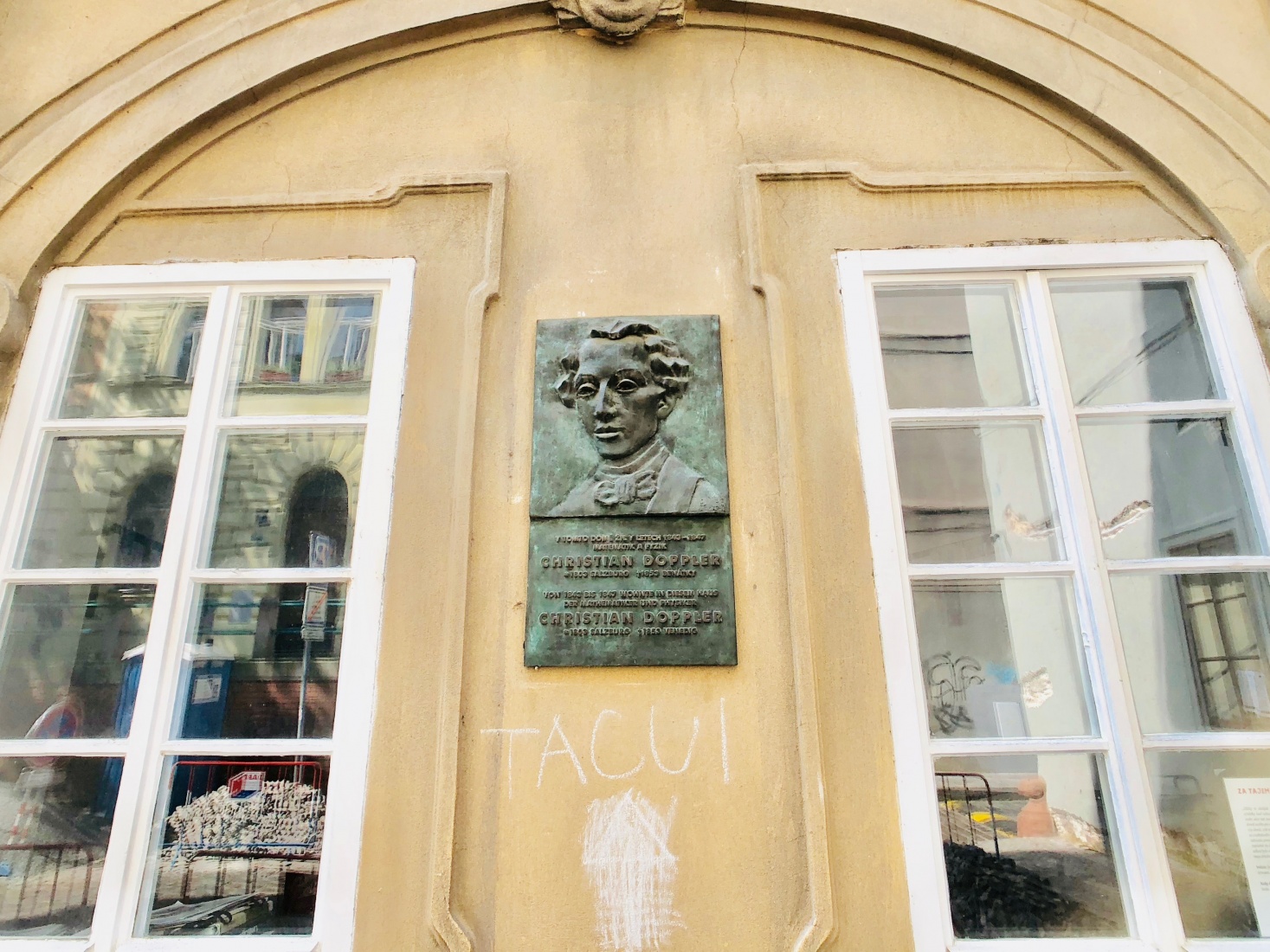

I had no idea Doppler had spent any time in Prague at all – and I wonder how many people living here know anything about him either. I was walking home one night from an Irish pub in the center of town – the James Joyce at U Obecního dvora 4 – and saw a memorial plaque on the side of a house. I took a closer look and it was Doppler’s. It reads simply that he lived in this house -- quite a nice place, by the way -- from 1843-47.

There’s not much information on Doppler’s life in Prague. By all accounts, he was a typical 19th-century Habsburg-era academic. He was born in Salzburg and worked various academic appointments across the empire.

The bourgeois revolution of 1848 found him in a precarious spot, though, which proves being a native Austrian during the time of Austria’s greatest dominance could have negative consequences as well. When the middle classes, particularly the Hungarians, rose up against the Habsburgs that year, Doppler, unfortunately, found himself at a Hungarian university, in the Slovak city of Banská Štiavnica. He had to high-tail it out of there fast, and ended up riding out his career safe and sound in Vienna.

I’ll wrap up this post with possibly the most convincing argument of all that Prague could credibly lay claim to being the home of modern astronomy, and it has nothing to do with actual astronomers.

Think about it for a second. Aside from Prague Castle and Charles Bridge, what’s the most significant tourist attraction in the city? It’s the Astronomical Clock on the southern face of the Old Town Hall, of course. (The clock even has the word "astronomy" in the name.) In fact, it’s not a clock at all; it’s what astronomers call on “astrolabe” – a scientific instrument for determining the relative positions of stars and planets.

Prague’s astronomical clock has been dolled up over the years with models of the apostles and medieval figures that move and dance on the hour, but it’s actually a sophisticated scientific instrument. In addition to telling Central European Time, the clock’s rings show Babylonian time (calculated from sunrise to sunset), Old Bohemian Time, sidereal time, the phases of the moon, the positions of the zodiac – indeed, just about anything a budding 15th-century astronomer might need for their work.

There are plenty of websites out there to help you understand the clock and astrolabe. Find a fairly straightforward explanation here, and a more complicated version here.

Parts of the clock date all the way back to 1410 – in other words, nearly two centuries before Tycho and Kepler came along and began putting it all on firmer scientific footing. It seems Prague was somehow destined to play a major role in astronomy. You might even say it was written in the stars.

This first part of this two-part series on Prague and astronomy appeared last week under the heading: Part 1: Tycho Brahe & Johannes Kepler.