At first glance, Prague is not an ideal astronomy city. It's a landlocked, northern European place, with a continental climate that includes a lot of cloudy nights. I know the reality first-hand. My birthday falls near the middle of July – the time of year with the highest statistical likelihood of clear skies – and even then there’s a 42% chance of rain. Try planning a birthday party in the park sometime and you’ll see what I mean.

There isn’t even a remote mountain nearby on which to plant an observatory. Of course, in the 16th and 17th centuries, when most of the important astronomical work here was carried out, there wasn’t much in the way of light pollution to dim celestial objects – except for the occasional citywide fire.

So how was it then that over the years, given these limitations, Prague managed to attract the keenest astronomical minds of their time? There must be something in the water.

Two of the most important astronomers to live here were the Danish observer and theoretician Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and his understudy and successor, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630). They were a highly dysfunctional duo whose skill sets, nevertheless, overlapped in ways that would change the course of astronomy forever.

First off, my apologies to Danish readers out there who might feel that Tycho Brahe is part of their patrimony, and not Prague’s. Tycho worked as an observer and star-charter for decades in the late-16th century for the Danish crown, which at the time was eager to show the world that Denmark wasn’t just a bunch of viking yokels, but had some scholarly Renaissance ambitions of its own.

By contrast, Tycho spent only two short years in Prague (1599-1601) in his capacity as imperial astronomer for Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II. Nevertheless, it was arguably during this brief span – and particularly his association with understudy Kepler -- that Tycho cemented his enduring scientific reputation.

Tycho had come from noble Danish stock and managed to cajole the Danish king into building him a massive observatory in 1576 at Uraniborg, on the island of Hven (now part of Sweden). The Danes spent lavishly on Tycho and he rewarded them (and all future astronomers) with reams of notebooks filled with highly detailed charts of the stars and planets. Those charts, which he would continue working on and refining in Prague, would prove crucial to Kepler as he formulated his own laws of planetary motion in the early 17th century.

Tycho was a prodigious drinker, womanizer, and dueler (he’d even had his nose sliced off in a duel as a student), but he was also highly concerned about his legacy. At the start of the 17th century, that meant being viewed as both a good scientist and a faithful follower of scripture – even as those two requirements began to diverge wildly in practice.

A generation earlier, the Polish mathematician Copernicus had opened up an ecclesiastical can of worms by positing, convincingly, that the sun (and not the earth) was at the center of everything. This seemed to fly in the face of both common sense and the teachings of the Church, which viewed the earth as the center of God’s creation.

Tycho felt it was his role to find a compromise somewhere between observable facts and scripture, and he eventually settled on an idea called “geo-heliocentrism.” Under this system, the sun, moon and stars all revolved around the earth, while the solar system’s five known planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) orbited the sun. This model was highly convoluted, to be sure, but succeeded in preserving the primacy of the earth while staying faithful to observable scientific facts.

Kepler would eventually debunk all of this in due course, but I don’t want to get ahead of myself here.

Tycho was large in life, but maybe even larger in death. He died suddenly in 1601 of a burst bladder after having attended an imperial banquet (he was apparently too respectful of the emperor to leave the room in order to relieve himself).

His passing, at the age of 54, set off all manner of speculation (only resolved four centuries later) that he’d been poisoned. It was argued at the time that both Denmark’s relatively young king, Christian IV, and even Kepler himself (to get at Tycho’s astronomical data) may have wanted to murder him. The issue was settled once and for all by an official Danish inquiry in 2010 that determined Tycho had died of natural causes.

(To get a flavor for all the intrigue surrounding Tycho's death, check out this New York Times story.)

The interaction between Kepler and Tycho was surprisingly brief, lasting only a few months in 1601 before Tycho's bladder burst. Kepler had journeyed up to Prague that year from the Austrian city of Graz, where he'd worked as a mathematics professor. By all accounts, he intended to remain in Prague just a couple of years, but after Tycho’s passing the emperor asked him to stay on. Kepler wound up spending more than a decade here, from 1601 to 1612.

The relationship between a bawdy Dane like Tycho and the more abstemious German (and Lutheran) Kepler was naturally fraught. Despite their differences, though, Tycho saw in Kepler a younger man who could preserve and extend the Dane’s legacy. Tycho, on his deathbed, apparently asked Kepler to dedicate his life to proving Tycho’s elaborate geo-heliocentrist theory so that the Dane "would not have died in vain."

In an irony perhaps of astronomical proportions, however, Tycho’s meticulous data would lead Kepler eventually to dismantle geo-heliocentrism entirely and relegate it to the dustbin of history.

(While digging around on the web, I found this fantastic video on the Tycho-Kepler rivalry by a group of 8th graders from California. It’s well worth a watch.)

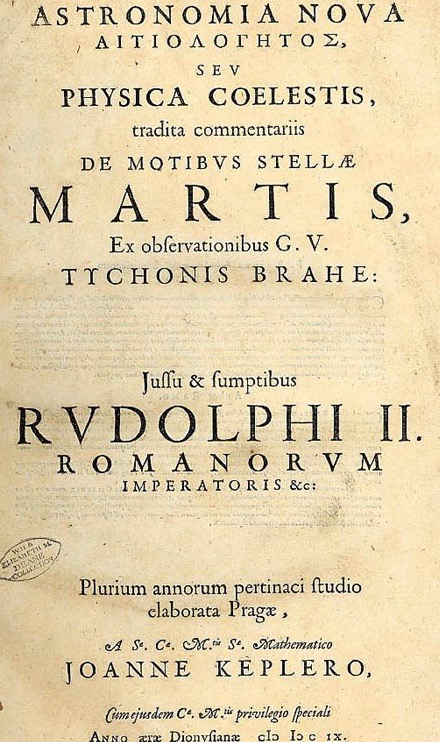

Tycho’s observations eventually led Kepler to formulate his three laws of planetary motion, which marked a profound advance in our understanding of the solar system and eventually severed any surviving link between astronomy and theology.

Without getting overly technical, the laws can be summarized as follows: 1) planets orbit the sun in ellipses, and not circles; 2) planets travel faster when closer to the sun and slower when further away; 3) the further a planet is away from the sun, the longer it takes the planet to orbit the sun.

These all seem like common sense now, but they established a foundation that later groundbreaking scientists, such as Sir Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley (of Halley’s comet fame), would build on.

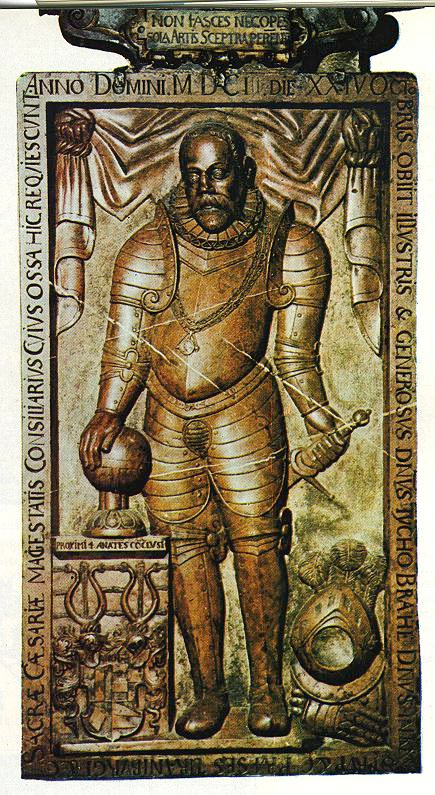

For visitors to Prague, the main Tycho sight is the Dane’s striking tombstone at the Church of Our Lady Before Týn, on Old Town Square. The outlines of Tycho’s prosthetic nose are clearly visible on the stone’s relief (see photo). While in the service of Prague Castle, Tycho spent days and nights at the beautiful Renaissance Summer Palace in the gardens north of the castle. Some of Tycho’s enormous sextants and other observational equipment are on display at Prague’s National Technical Museum in the Prague neighborhood of Holešovice.

As for surviving Kepler sights around Prague, alas, there are not too many. Kepler’s former apartment in the Old Town at Karlova 4 is marked by a plaque over the entrance, but it's no longer open to the public (the small museum inside that once housed some Kepler memorabilia closed in 2017). There’s talk of moving the museum’s contents to the National Technical Museum, but it’s not clear when that will happen.

In next week’s post, I write about Albert Einstein’s and Christian Doppler's days in Prague: "On Einstein & A Guy Named Doppler." Continue reading here.