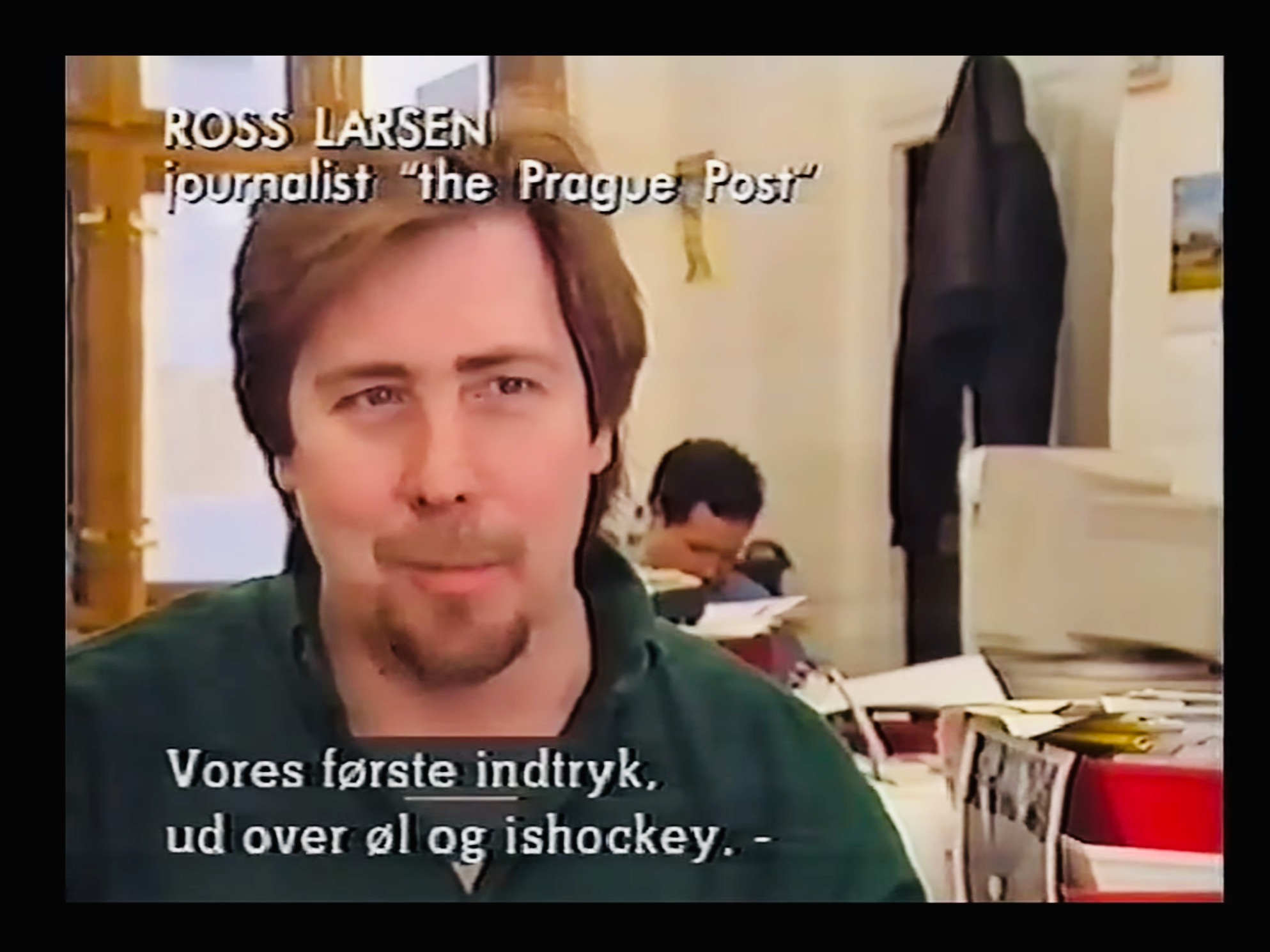

By 1993 and into 1994, the international buzz around Prague’s “Left Bank” had reached fever pitch. In June 1993 (nearly 30 years to the day as I write this post), Smithsonian magazine printed a glossy, 10-page article titled “All They Are Saying Is Give Prague a Chance,” by writer Stanley Meisler. The spread was filled with colorful photos and featured upbeat interviews with prominent Czech student leaders, like Martin Mejstřík, as well as influential expats, such as The Prague Post’s Lisa Frankenberg and Prognosis editor John Allison.

Meisler wrote breathlessly about Prague’s comparison to Paris, the universal appeal of Czech President Václav Havel, the arrival of thousands of young Americans, and the dreams everyone had back then of not just making money but making history. The Smithsonian article was just one of dozens of similar pieces on the Prague expat phenomenon, but the fact that such a widely-respected publication had devoted so much real estate to the story affirmed its legitimacy and pushed it firmly into the American cultural consciousness.

As I was researching this post, I pulled out a wrinkled, yellowed copy of that Smithsonian article from a box of old papers I had in my office. As I reread the story, flashes of that early excitement leapt off the pages like the flecks of paper dust in the air. I could easily recall the people and places. Even more vividly, I could hear in my mind the sounds of Prague’s omnipresent, early-‘90s soundtrack. Just as the local Czech and expat worlds had merged together seamlessly back then, so too did the songs on the radio. One minute, Linda Perry of “4 Non Blondes” would be screaming (at the top of her lungs) “What’s going on?” The next moment, the Czech singer Lucie Bílá would be doing her own screaming in her impossible-to-avoid, “Láska je láska” (Love is Love). No one seemed to notice or care what language anyone sang in.

All these years later, I can still hear Michael Stipe’s lone, vulnerable voice crack with emotion in one of those popular REM anthems, like “Losing My Religion” or “Man on the Moon,” or U2’s Bono belt out “Mysterious Ways.” Just a couple of beats into any of these songs is all I need for the memories to come flooding back. When Bono sang the line, “She moves in mysterious ways,” it felt back then as if the “she” in the song were the city of Prague itself.

The timing of that Smithsonian article, the summer of 1993, corresponded to the opening of several important expat businesses that would come to symbolize the expat scene in popular memory. In July 1993, I and four American friends started The Globe Bookstore & Coffeehouse, which emerged as a popular hangout spot for the new arrivals (and a place where visiting journalists could easily find subjects to interview for all of their “Left Bank” stories).

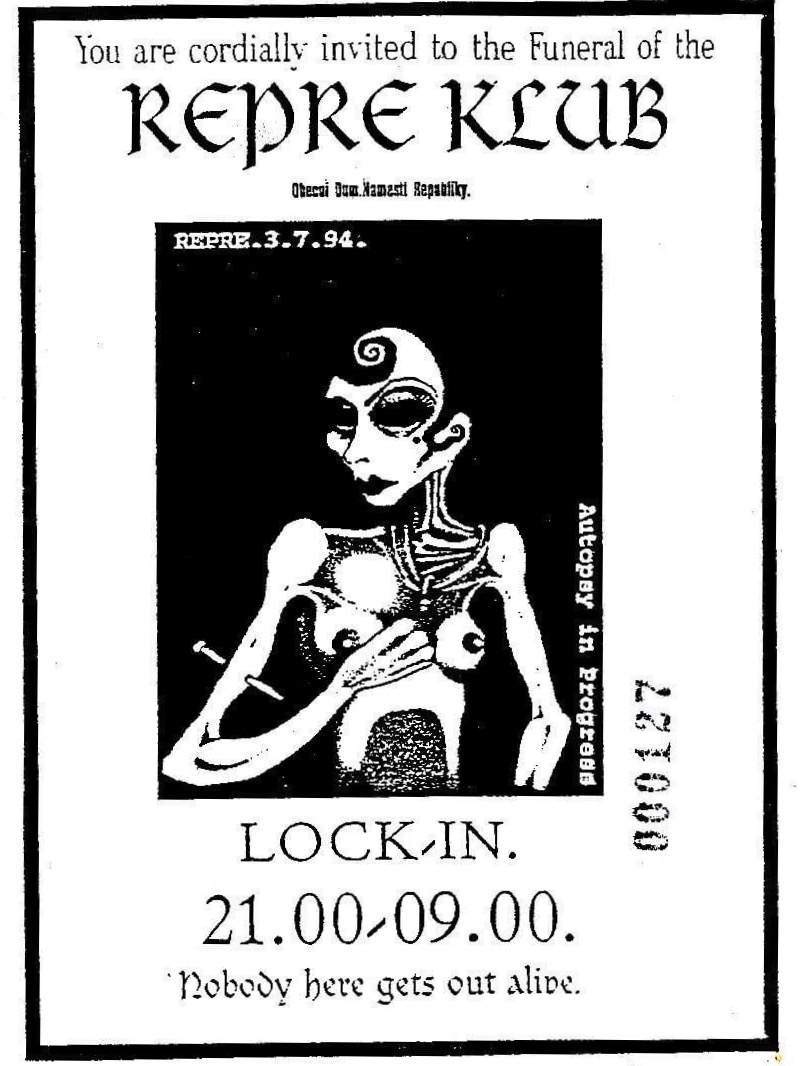

An even more-visible marker of the reach of the expat scene came when Canadian Glen Emery, the expat owner of Jo’s Bar, and his American business partner, John Bruce Shoemaker, signed a year-long lease to operate a complex of bars and clubs inside Prague’s opulent Art Nouveau-style Municipal House (Obecní dům). That agreement brought the expat circus directly into the heart of one of the Czech Republic’s most-treasured buildings. The duo transformed the structure’s ground-floor space into an American-style café and added several louder, late-night establishments, including the always-packed Repre Club, to the opulent salons of the building’s basement. An adjoining pub, The Thirsty Dog, attracted the attention of visiting musician Nick Cave, who was passing through town for a concert. Cave was so impressed by the place he dedicated a song to it, complete with the now-famous refrain: “I'm sitting, feeling sorry in The Thirsty Dog.”

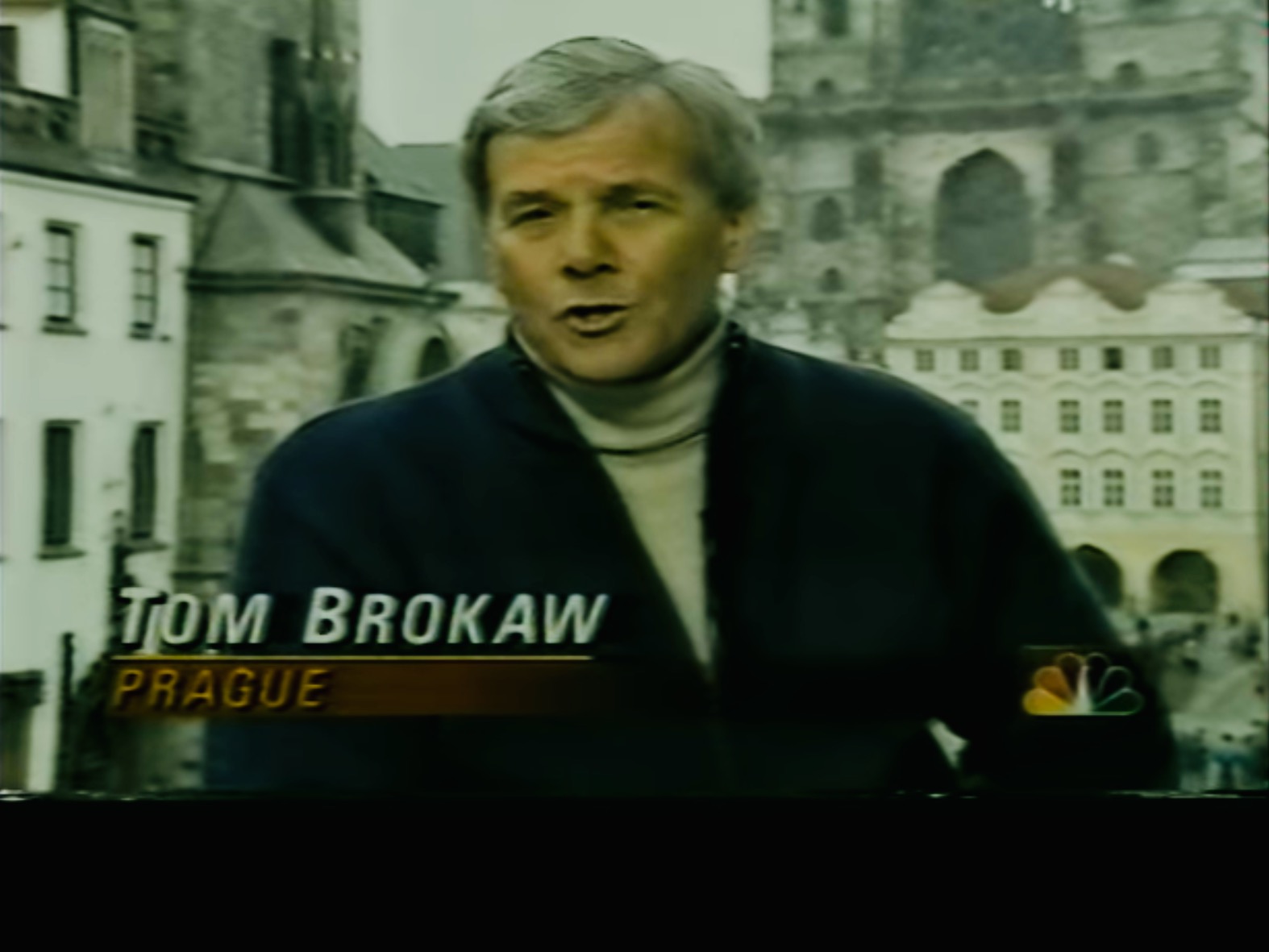

That early expat wave crested sometime around early-January 1994, with the visit to Prague by U.S. President Bill Clinton. Both the American leader and his Czech counterpart, Václav Havel, were at the height of their international popularity. Media outlets from the U.S. and around the world salivated at the prospect of covering the two charismatic leaders pitched against a dramatic, postcard backdrop of hilltop castle and statue-lined bridge. They gave the trip – including Clinton’s famous saxophone solo at Prague's Reduta Jazz Club and his pub night out with Havel and prominent Czech author, Bohumil Hrabal – minute-by-minute coverage. U.S. television networks set up studios on balconies around Old Town Square from where they beamed live images of the landmark, twin-spired Týn Church directly into American living rooms.

Sometime toward the latter part of the decade, starting around 1996 or 1997, the energy of that first wave started to sputter and burn itself out. Many foreigners simply decided it was time to return home. Expat communities, by their nature, tend to be temporary. Over time, people either integrate with the host culture or pull up stakes and leave. Significant inflows of expats kept coming to Prague and the Czech Republic throughout the rest of the ’90s and well into the 2000s, but without the massive media hype or the inspiration (or baggage) of being part of some grandiose "Left Bank" phenomenon. These future waves of foreigners tended to be smaller, less ambitious in their pretensions and more realistic about what they hoped to achieve.

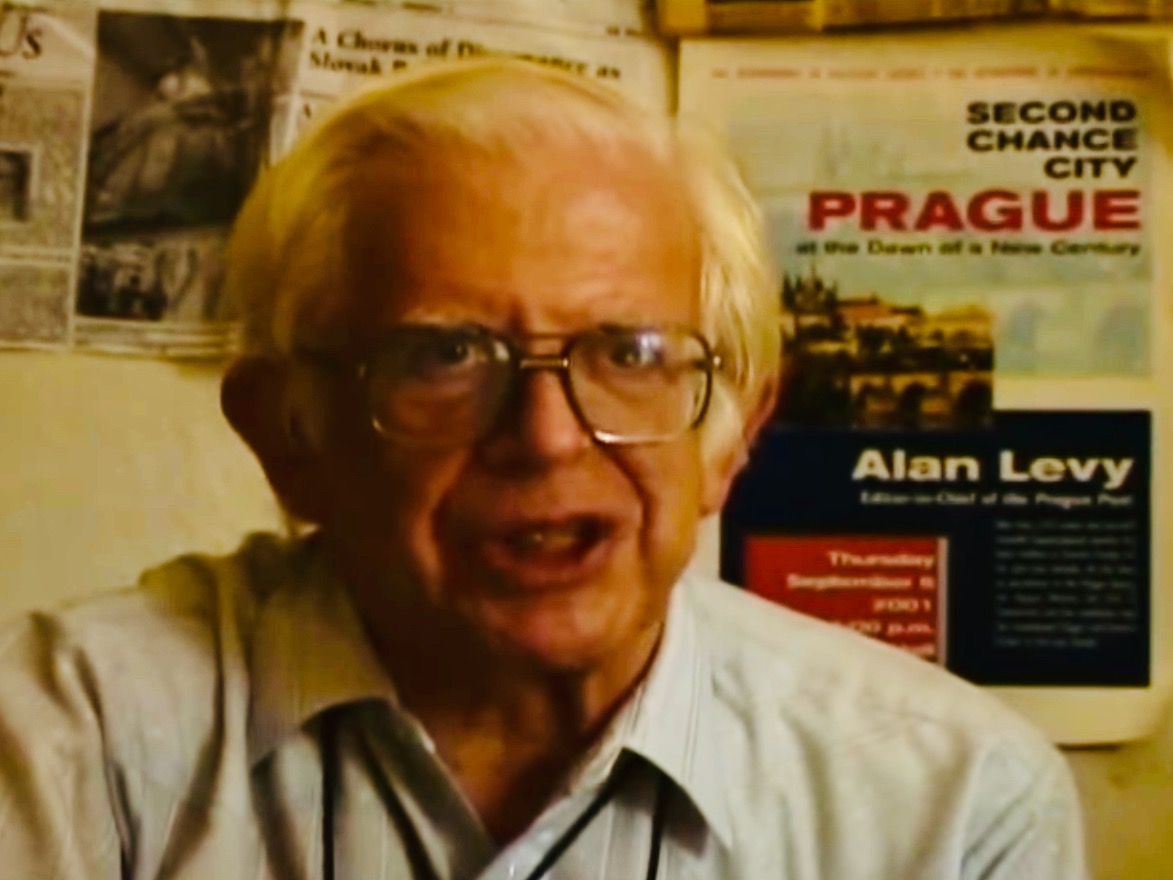

As the number of arrivals declined, the organs of the Czech state regained their footing. The police cracked down more frequently on illegal businesses and the ministries stepped up collections of taxes and social-security payments. This steady recovery of the state had been necessary for restoring stability, but it also dampened that initial Wild East enthusiasm. Within a few years, the Czech Republic evolved from a place where, in the words of Alan’s original essay, “anything goes” to essentially what it is today: a relatively normal, medium-sized European country.

It’s now more than three decades since Alan Levy’s “Left Bank of the ‘90s” essay appeared on the front page of The Prague Post. It’s clear, by now, that his lofty call that Prague’s expats would go on to write great works of literature – specifically great works of English literature – likely didn't come to pass. As early as 1995, the American writer Bruce Sterling, in an article for Wired magazine titled “The Triumph of the Plastic People,” pointed out what seemed obvious (even back then): the literary scene lacked a singular “Prague approach” or philosophy that could define an emerging group of authors. When viewed from a distance of thirty years, the explosion in the number of young foreigners who came to Prague was more of a curiosity or media event than any kind of turning point in global culture (as anyone back then -- with the possible exception of Alan Levy himself -- could have told you).

What’s often overlooked, though, and something that might surprise readers here, is the fact that many talented writers, poets and playwrights, from countries all around the world, actually did come to Prague in the years after the Velvet Revolution and wrote some very good books. A short list (there were many others) would include Caleb Crain (Necessary Errors); Robert Eversz (Shooting Elvis); Myla Goldberg (Bee Season); Aaron Hamburger (The View from Stalin's Head); Jonathan Ledgard (Giraffe); Tom McCarthy (Men in Space); Brendan McNally (Germania); Gary Shteyngart (The Russian Debutante’s Handbook); and Maarten Troost (The Sex Lives of Cannibals).

The extent of Prague’s literary scene went well beyond the works of these individual writers and encompassed a large and supportive ecosystem. This ecosystem included expat-run bookstores, like The Globe, as well as English-language newspapers, book-publishing companies, dozens of independent literary magazines and anthologies, writers’ festivals, public readings, theater companies, and even film studios. Anyone needing more proof need only look to Louis Armand’s exhaustive 900-page compendium, titled The Return of Král Majáles, which documented Prague's literary renaissance from 1990 to 2010 and the impressive body of work produced by the city's foreign-born writers. In the book, Armand drew links to earlier generations of writers working in the Czech capital in order to provide historical context for the later, 1990s' generation. While it’s probably true that Prague never became “Paris,” by any reasonable standard, the Czech capital hosted an important, viable, offshore literary colony in the 1990s that ran for several years.

It’s harder to pin down the impact that the early-90s’ influx had on the city of Prague and Czech Republic. A handful of those early expat hangouts, like Jáma or Little Glen’s, or even The Globe, have survived to the present day, but they no longer feel central to the city’s cultural life in the way they did back then. The majority of those early businesses, including the first shoots of the expat wave, like Laundry Kings and Red, Hot & Blues, have mostly closed down. Copies of all those early expat newspapers, magazines and literary reviews – publications that had once felt so timely and vital – now lie unread and gathering dust in the city’s second-hand bookstores and junk shops.

The enduring impact of the early-‘90s, I think, lies more in intangibles than in any surviving physical remnants, and the legacy is stronger and more positive than people generally recognize. At a minimum, the expat wave, and the many newspaper and magazine articles about Prague and the Czech Republic it spawned, greatly opened up the city and country to international tourism. The presence of so many young foreigners softened Czechoslovakia’s old Cold War image as a particularly hard-line state and took the edge off of those funny-looking diacritical marks that appear in the country’s difficult, unfamiliar language. Over time, given Prague’s beauty and central location, the tourists would certainly have come anyway, but the ease with which foreigners back then could live and thrive hastened the welcoming process and pulled Czechoslovakia, and later the Czech Republic, into the international tourism mainstream.

The expats also helped to open up Czech society to thousands of outside influences, both big and small. These ranged from relatively unimportant foreign imports, like better-quality pizza, coffee, burgers and bagels; to emerging cultural trends in music and literature; practical economic, political and legal know-how; and even big, academic ideas that have informed and enlivened debate in schools and universities. Often, these bigger ideas entered the culture through one of the many journals, anthologies, 'zines and papers -- some of them bilingual in English and Czech -- that thrived at the time.

To take just one small example, consider for a moment the contributions of the modest, bilingual English/Czech literary journal, “One Eye Open/Jedním okem.” The publication, started by an American expat and featuring writers from both sides of the former Iron Curtain, ran for just a handful of editions from 1993 to 2006, yet it introduced many novel ideas concerning feminism that continue to inform debate into the modern day. That first wave of newcomers fashioned an early pipeline to the outside through which imported attitudes and intellectual artifacts could flow freely.

Finally, the expats brought to the country a much-needed burst of energy and creativity in the aftermath of the fall of communism and Czechoslovakia’s first tentative steps toward democracy and free markets. It’s largely forgotten now, but the first couple of years after 1989 were not easy for the newly liberated city and country. There were lots of economic and transition worries, and then came the divisive parliamentary elections of June 1992, Havel’s snap resignation as president, and the eventual split of the country in 1993. The big wave of foreigners who moved to Prague helped in some small way to change the narrative. Suddenly, Prague and Czechoslovakia were hip, cool and at the center of the cultural zeitgeist.

On a more practical level, businesses like The Globe, which occupied the premises of a former communist-era laundry service, or even the short-lived transformation of the Municipal House demonstrated how old, familiar spaces could be creatively refashioned and reinvented. That transformation metaphor could easily be extended to many other parts of life. Over the years that I’ve lived here and witnessed the recovery of formerly neglected neighborhoods in Prague and seen similar revivals in Czech cities like Olomouc, Ostrava, Plzeň and Brno, I can still detect traces of that early enthusiasm. It’s by now become part of the city’s – and country’s – DNA.

*Some readers may balk at the term “expat,” which has fallen out of favor in some circles in recent years. I acknowledge the word carries with it the notion of privilege, but I’ve retained it here as the term commonly in use at the time. By “expat,” I refer merely to a person who has chosen to leave his or her home country but without necessarily the intention to stay away permanently.

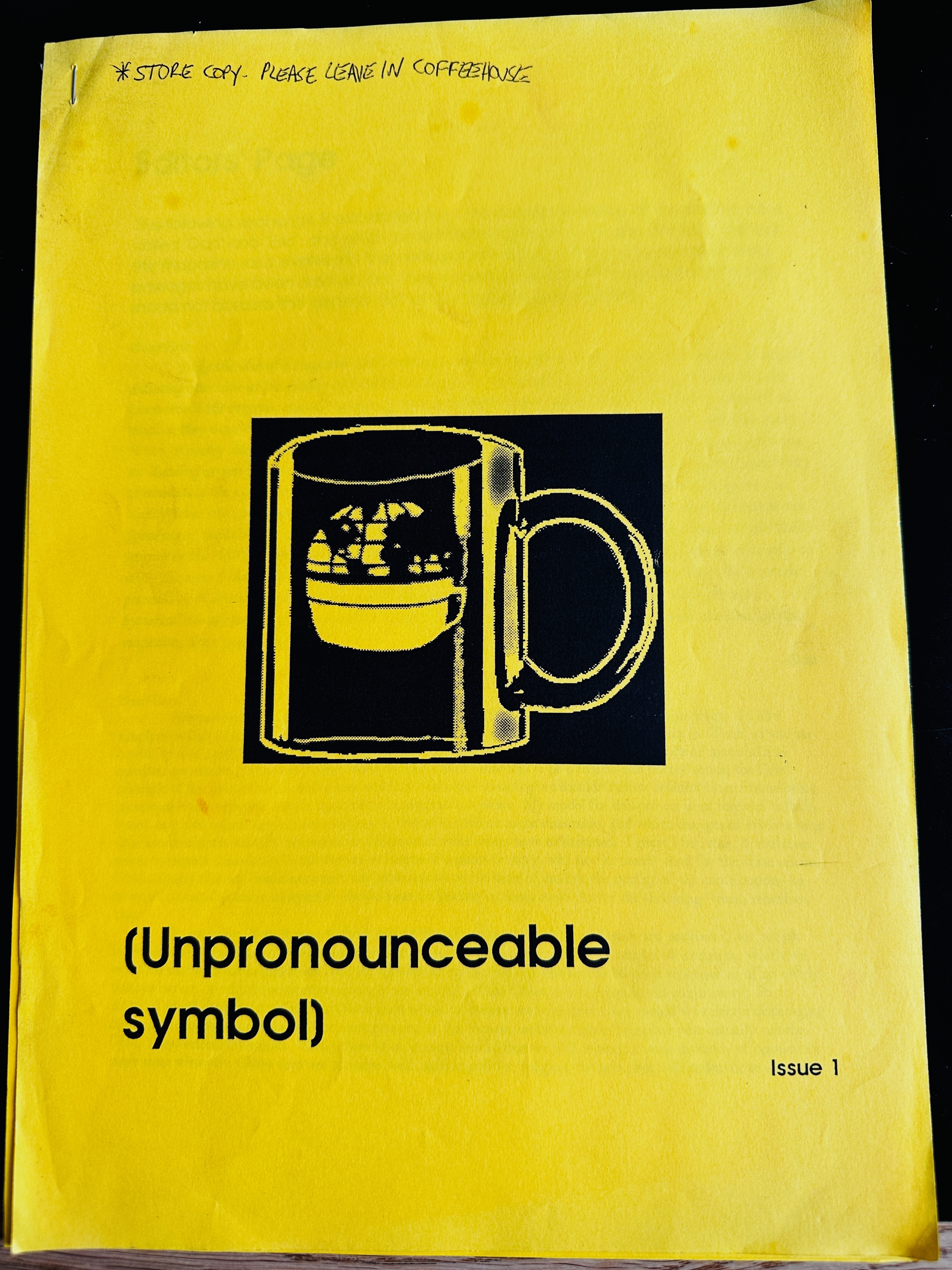

So great to see My very good friend JB Shoemaker’s (rip) photo here as well as stories about him and his exploits…I also had a couple of my wood-engravings published in “Unpronounceable Symbol” when I was there in 97…

Thank you Mark.

Thank you Mark for this reminiscence.

Great article. I lived in Prague from September 1993 to May 1994, so I was definitely there at the ‘peak’ of the period you wrote about in the article. I was an 18-year-old exchange student from New Zealand and it was my first time to visit Europe, my first time to get to grips with a foreign language and my first time to live away from home (or abroad for that matter). I used to hang out at the Globe and the Obecní d?m, as well as at the Velryba, which was another hot-spot in those days.

It was, unquestionably, a very special time in a very special place. You are quite right about the media coverage of the aspiring writers (I met many of them) and the hype around Havel, but you didn’t mention the fame of Milan Kundera at the time, and of ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Being’ in particular. It seemed to me that the reputation of Kundera as an intellectual, combined with that of Havel, left a gloss on the reputation of the Czech population as a whole, which contrasted with the (somewhat unfair) repuations of, say, the Poles, Russians and East Germans as Catholic fanatics, alcoholics and neo-Nazis respectively. That positive, intellectual reputation, contrasted with such horrors as the Romanian orphanages and the war and Yugoslavia, meant that the Czech Republic, and especially Prague, was the only place in Eastern Europe in the 1990s that could ever have played the role that it did.

I have met many Czech people who also regard that period as a magical time. I don’t think it was for everybody, but for those of a certain age it was paradigmatic.

Hi, thank you for reading and leaving a comment. I agree with everything that you wrote about, and in part one of this post wrote exactly of this gloss you mentioned with respect to authors like Milan Kundera. Find the link to part one in the post and give it a read. I think you will find it interesting. Best, Mark.

You are quite right. Somehow I skipped that section! Anyway, as I said, this is a great article and sums up a period that I guess didn’t really live up to its own expectations, as current events make so sadly clear.

Mark, what a great article and about a magical time in Prague and in the lives of those of us lucky enough to have experienced it firsthand. Of all the pieces I’ve read over the years about Prague in the 90s, and I’ve read far too many of them, yours best captures the spirit of the era, with incisive analysis and evocative writing to boot. Thanks for the memories – and for The Globe!

Thank you, Marc!