A few months after the Kavan affair, the newspaper faced another big reporting challenge, and this one affected my business desk directly. If I have any regrets from my days at the paper, it would be the way that we covered Czechoslovakia’s “voucher” privatization program for selling off state-owned assets to private hands. The program began in late-1991 and lasted throughout much of 1992. I still kick myself, thirty years later, for not having spotted the potential weaknesses in the way the scheme was rolled out and for not recognizing the ways that it could be – and was – abused for private gain at the expense of the public good.

The program was originally conceived to help the country reinvigorate its state-owned companies and industries. Some companies were in relatively good shape, but others had been starved of investment for years and were badly in need of modernization. The idea behind the scheme was relatively simple: ordinary citizens would be able to purchase booklets of vouchers, which they could then use to “invest” in companies and, in effect, become shareholders. On paper, the idea looked attractive. It would allow average citizens to participate in the market economy and even profit directly from Czechoslovakia’s industrial recovery. The transfer of ownership would take place relatively quickly. It would also be reasonably transparent, as the companies taking part would be listed (and their economic results disclosed) in public records and the media.

There were plenty of red flags too, and to our credit at the paper, we reported regularly on the dangers as well. The main one was the fact that a voucher scheme like this one had never before been tried on such a vast, national scale. There were also legitimate questions about whether average citizens, who had just emerged from four decades of communist rule, would have the necessary skills to evaluate company balance sheets. The scheme would inevitably lead to societal inequities, as some investors, by chance, placed their vouchers in successful companies, while others chose shakier companies and lost money.

The potential dangers were clear, but what we at the Post failed to foresee, as did many others, was how a handful of large and powerful investment funds would come to dominate and corrupt the process. These funds abused their positions, consolidated their holdings, stripped companies of valuable assets, and then sold these assets off to the highest bidders. In the process, the owners of the funds themselves pocketed enormous personal fortunes. In fairness to the voucher-privatization scheme, and to its early advocates like Klaus, the plan’s shortcomings came not so much in the concept itself, but rather in the legal system’s failure to regulate how the funds behaved. These failures eventually cost the country hundreds of millions of dollars in stolen assets and damaged its reputation for years in the eyes of legitimate international investors.

In January 1992, just as the voucher program was getting underway, I and one of my colleagues at the paper, Boris Gomez, got the chance to interview the man who would later become one of the most infamous of these investment-fund bandits: Viktor Kožený, then president of the Harvard Capital & Consulting company. Kožený would go on years later to earn the nickname, “The Pirate of Prague,” for his role in stripping and selling off millions of dollars of Czech assets, but at the time of our interview, he’d recently emerged as arguably the most popular man in the country. Just a few weeks earlier, the 28-year-old Czech and recent Harvard University student electrified the public’s interest in the voucher program by boldly offering to pay his fundholders a ten-fold return on their investment within a year. Prior to Kožený’s pledge, Czechs and Slovaks had shown only lukewarm interest in the scheme. Many people seemed bewildered, at first, by the idea of purchasing voucher booklets and assigning points to various companies and funds. The cost for participating in the program, 1,000 Czechoslovak crowns, was not insubstantial either; it represented about a week’s wage at the time. Suddenly, competing funds moved to match or exceed Kožený’s offer and the voucher scheme assumed the feel of a nationwide Powerball lottery. For the chance to turn 1,000 crowns into 10,000 in a year, everyone wanted in.

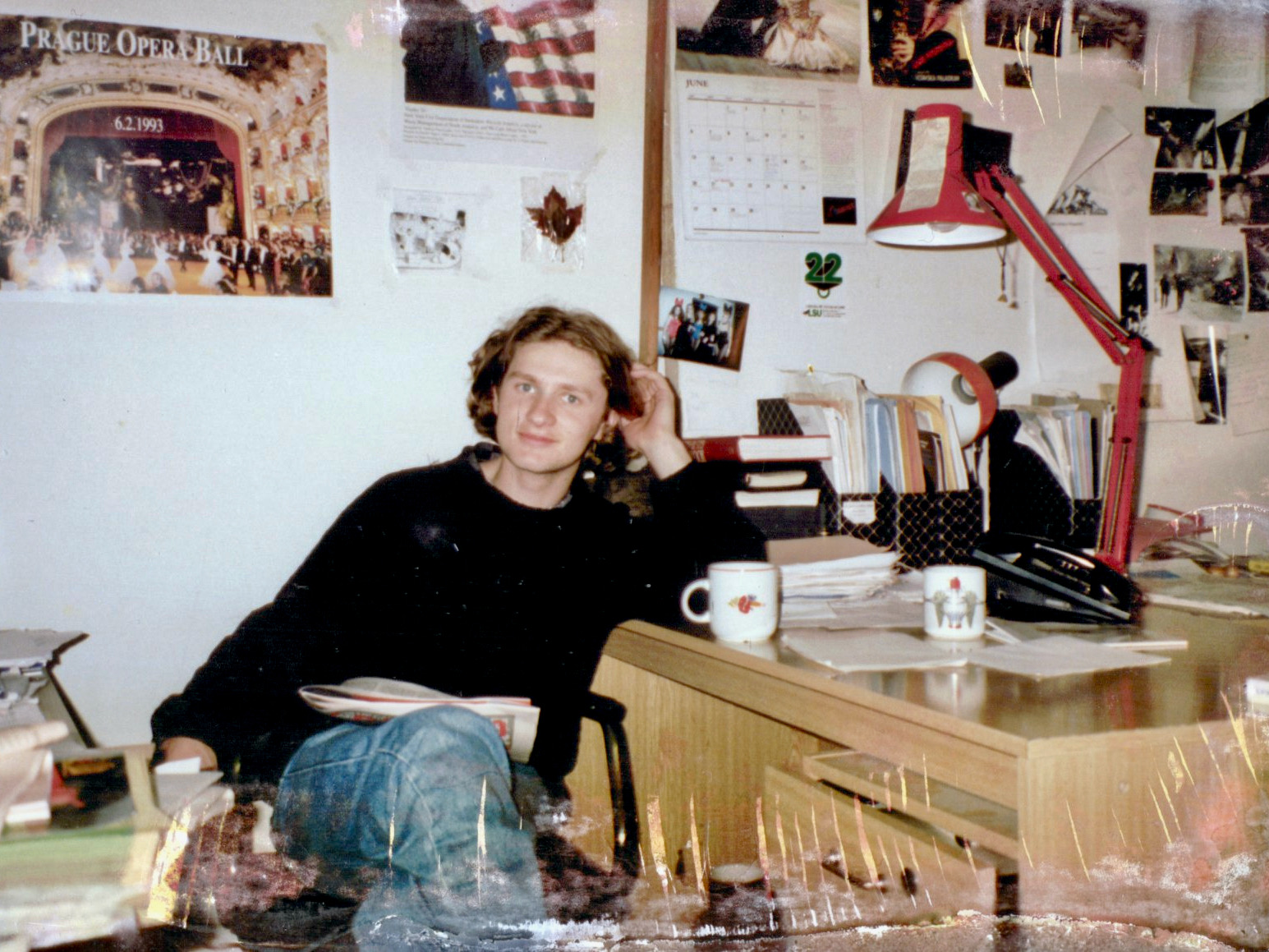

Looking back, that interview with Kožený was one of the strangest I ever conducted at the Post or at any point in my career. I now see warning signs that I failed to pick up on at the time. The first oddity was the simple fact of the company’s modest headquarters, which were located not in the center of the city, but rather in a remote outlying district. For one of the country’s most-successful investment funds, a fund that would go on to attract more than 800,000 Czech and Slovak investors, its offices were unusually small and empty. The second thing was just how young and inexperienced Kožený appeared. At 28, he was three years younger than me and looked much more like one of those fresh-faced Americans who had come to Prague to get drunk and write poetry than someone in charge of a major investment fund. I expected to find a mature, investment-banker type. The man sitting across the desk was more like a child, with a soft, round face, wisps of curly hair, and a big grin that he wore throughout our discussion. It seems inconceivable now that Czechoslovakia would ever entrust such a large chunk of the economy to a person like this.

As we started the interview, I pulled out a piece of paper to record Kožený’s answers and realized I’d forgotten to bring a pen. I looked over to Boris for help, but he shook his head. He had brought only one. Kožený laughed and made a joke about journalists who don’t carry pens. He then reached into his pocket and gave me one of his own. The irony was not lost on any of us. I would be trying to trap the future “Pirate of Prague” by using his own pen.

Looking back on the transcript, we focused our questions on the big issues of the day (which now seem insignificant in retrospect). These included whether Kožený actually attended Harvard University (he said that he had – though the fund itself had no connection to the school) and whether he had sufficient means to make good on his promise of a ten-fold return (he said that he arranged contingency financing with other banks). At the time of the interview, I had never before considered the idea of asset-stripping – and the infamous word “tunneling” (tunelování) that would soon enter the Czech lexicon had no special meaning to me other than digging through dirt. Neither Boris nor I trusted Kožený – and we both detected a shallow opportunist – but we also didn’t fully understand his game. If I had any inkling at the time of what he was really planning, I would certainly have asked different questions.

The Czech Republic wasn’t Kožený’s only voucher-privatization victim. In the late 1990s, according to news reports, including a lengthy article that appeared on the Fortune magazine website, Kožený later took his act to Azerbaijan, where he allegedly defrauded a group of American investors as part of a plan to acquire a stake in Azerbaijan’s lucrative state oil monopoly, SOCAR. For that scheme, he reportedly raised hundreds of millions of dollars. When the plan later fell through, he stood accused of pocketing a significant share of his backers’ money. One of those backers, ironically, was my old school, Columbia University, which reportedly lost $15 million. As of this writing, Kožený remains exiled in the Bahamas and faces international arrest warrants from both the US and Czech Republic.

Certainly, the most challenging – and painful – story for the paper that year was the future of the country itself. When I first started at the Post, the question of Slovakia’s independence already hung thick in the air, but opinion polls still showed majorities of both Czechs and Slovaks either “strongly” or “moderately” supporting a common state. Over the course of the year, the forces that fueled the breakup emerged so suddenly and the consensus over unity eroded so quickly, that before we could catch our breath, it seemed, the country no longer existed. To this day, I’m not entirely sure who or what caused the breakup – or indeed whether or not it was a good or bad outcome – but it offered a lesson in the impermanence of things and a reminder that revolutions inevitably bring with them unintended consequences.

Looking at the headline from the Post’s very first edition, “A Chorus of Dissonance As Slovak Referendum Looms,” it’s obvious that we were transfixed by the country’s status from the very start. That story concerned the difficulties that Havel and his allies then faced in building support for a national referendum, involving both Czechs and Slovaks, on a common state. That referendum never took place. It was ultimately bogged down by disagreements over how it would be worded, when it would take place, and whether there would be one federal referendum or two republic-level votes (one in the Czech lands, the other in Slovakia). In the latter case, no one seemed to know what would happen if one republic voted for unity and the other to divide.

The issue of Czechoslovakia’s future dominated our front page for the duration of my time at the paper. First came the depressing moment, in late October 1991, when Havel was pelted by eggs tossed by Slovak separatists at a speech in Bratislava. Then came Havel’s gloomy New Year’s Day address on January 1, 1992, when he lamented the fact that no progress had been made on the outlines of a future state. Around that same time, the Federal Assembly, formally and finally, rejected Havel’s request for a referendum. Not long after that, in February 1992, the presidium of the Slovak parliament failed to approve a draft treaty that would form the basis of a new national constitution. By this time, it became clear to all of us at the newspaper – and to everyone else in the country – that the differences between Czechs and Slovaks had become unbridgeable.

At the Post, we greeted each new step toward dissolution with yet another notch of sadness. It’s hard for me to explain here, in retrospect, how we as foreigners developed such a strong emotional attachment to a united Czechoslovakia. I wrote above that the paper always aimed to present an unbiased viewpoint. That goal of objectivity certainly applied to policy differences between the political parties and other disagreements. In a bigger sense, though, we were neither unbiased nor objective when it came to the country itself. We rooted strongly for Czechoslovakia’s success, and that desire ultimately transferred to support for a unified state. I also recognize now that we tended to see the issue through Prague- or Czech-centric lenses. The Post employed few, if any, Slovaks at the time, and I don’t think any of us truly understood the legitimate reasons – economic or historic – why Slovaks might want to have their own country.

In June 1992, Czechoslovakia held an important parliamentary election that would set the future course of the country. That vote affirmed in power arguably the country’s two most-stubborn and unbudgeable politicians: Klaus on the Czech side and Vladimír Mečiar, the leader of the populist “Movement for a Democratic Slovakia,“ on the Slovak. Not long after the election, the two men met in Bratislava to hash out Czechoslovakia’s future but failed to make any meaningful headway. The debate was civil, but the country was finished.

Havel, who was still Czechoslovakia’s president, emerged from the impasse looking not unlike a tragic figure in one of his own works of absurdist theater. With no way of stopping the break-up, he stepped down as president on July 20, just minutes after the Slovak national council voted in favor of sovereignty. In words that might have appeared in King Lear, one of his favorite Shakespearean tragedies, Havel said, “I cannot bear responsibility for developments I can no longer influence.”

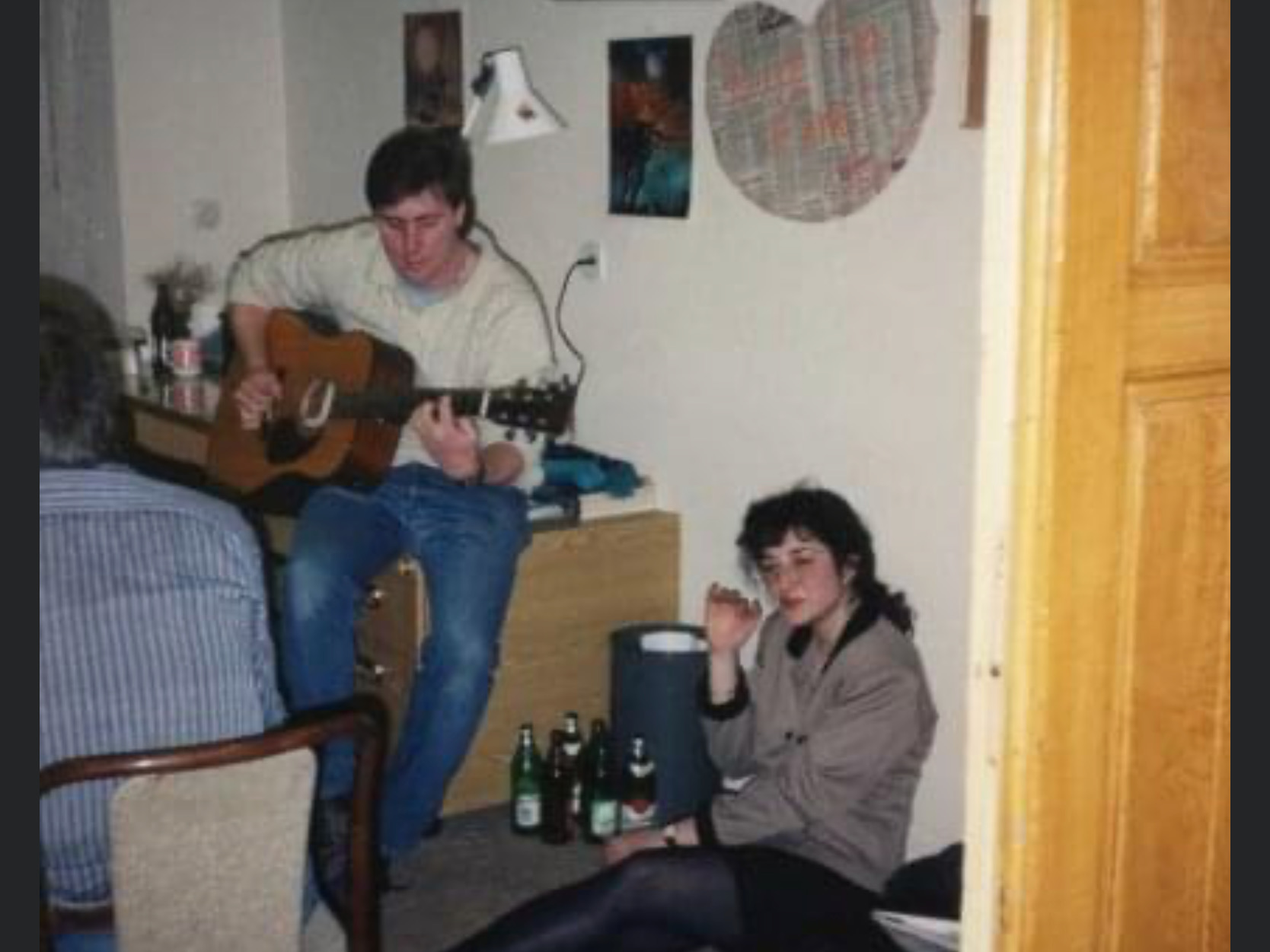

In August, as Klaus and Mečiar met once more to finalize plans to divide the country – this time beneath the trees behind the celebrated Vila Tugendhat in Brno – we at the Post planned our own picnic to mark the split. The setting for our gathering wasn’t quite as lavish: the scruffy back garden of the sprawling Prague “Nový Barrandov” housing project. The somber vibe, though, was similar. The picnic’s host, a young American reporter named Bill, was a talented musician, and at one point he pulled out his guitar to play. As news reports of the breakup blared from a nearby radio, Bill struck up the opening chords to a classic Lynyrd Skynyrd song. It was “Sweet Home Alabama,” but on that day, in solidarity with the soon-to-be-defunct Czechoslovakia, we sang it together as “Sweet Home Bratislava.”

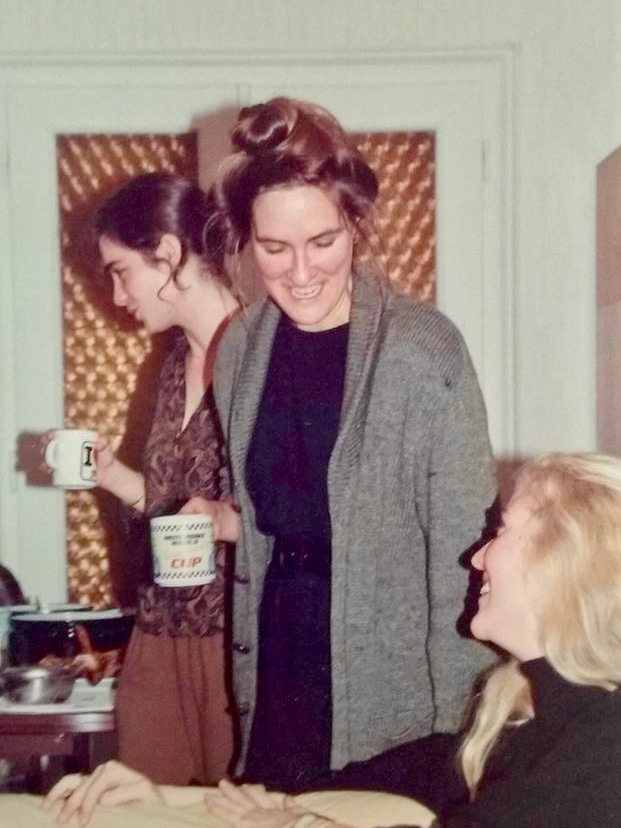

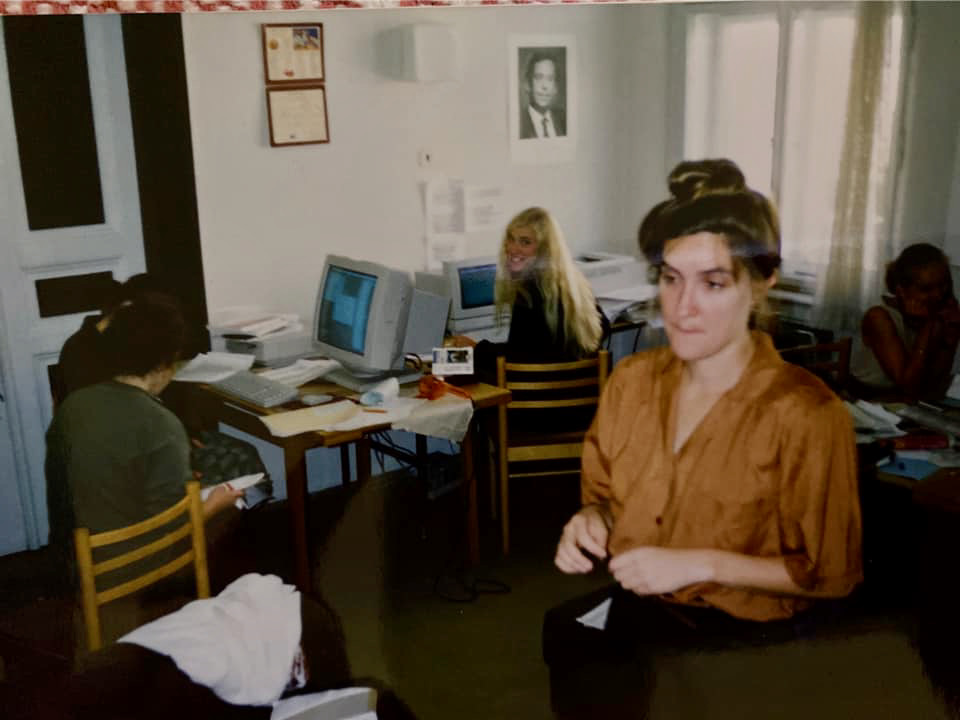

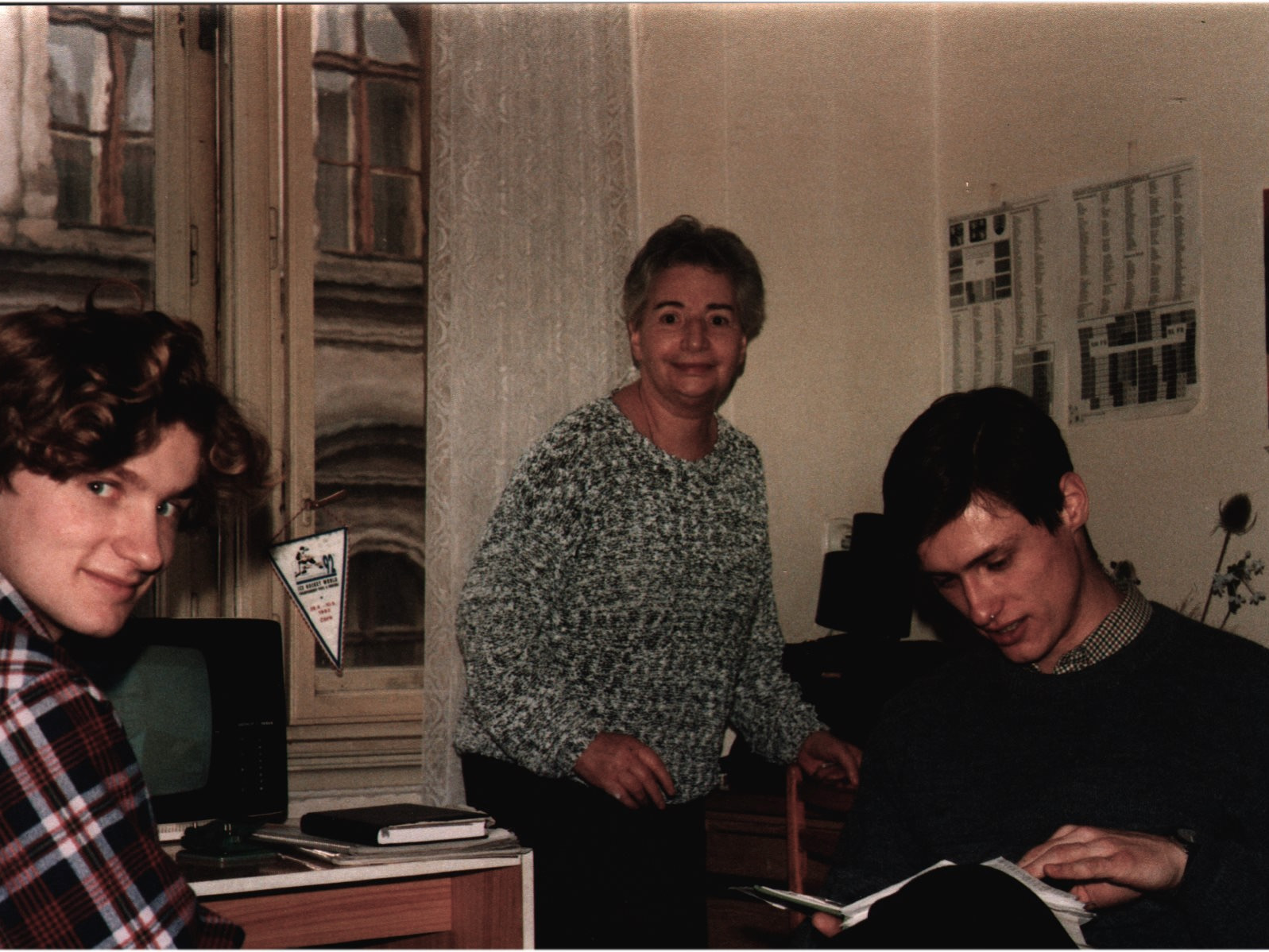

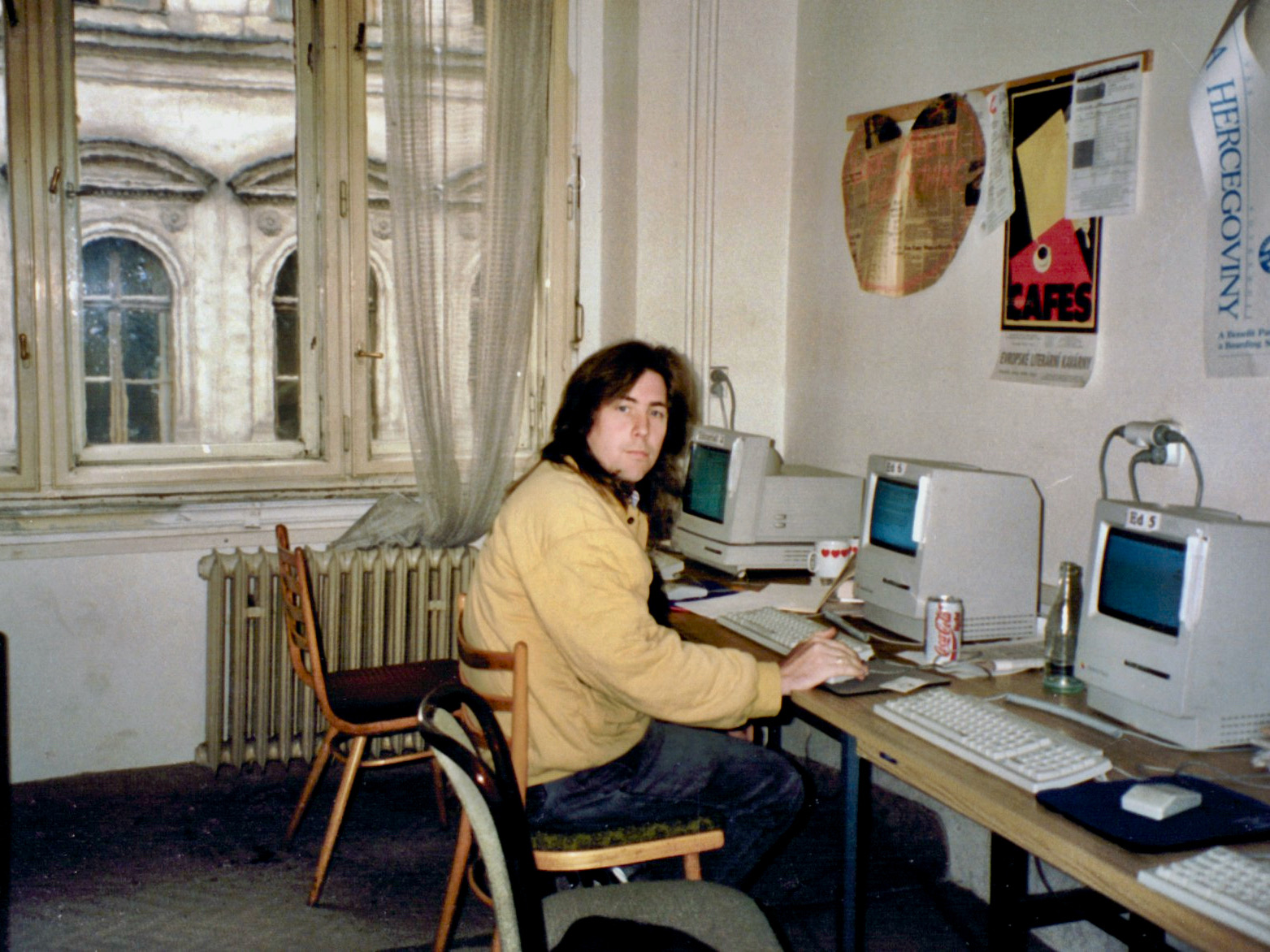

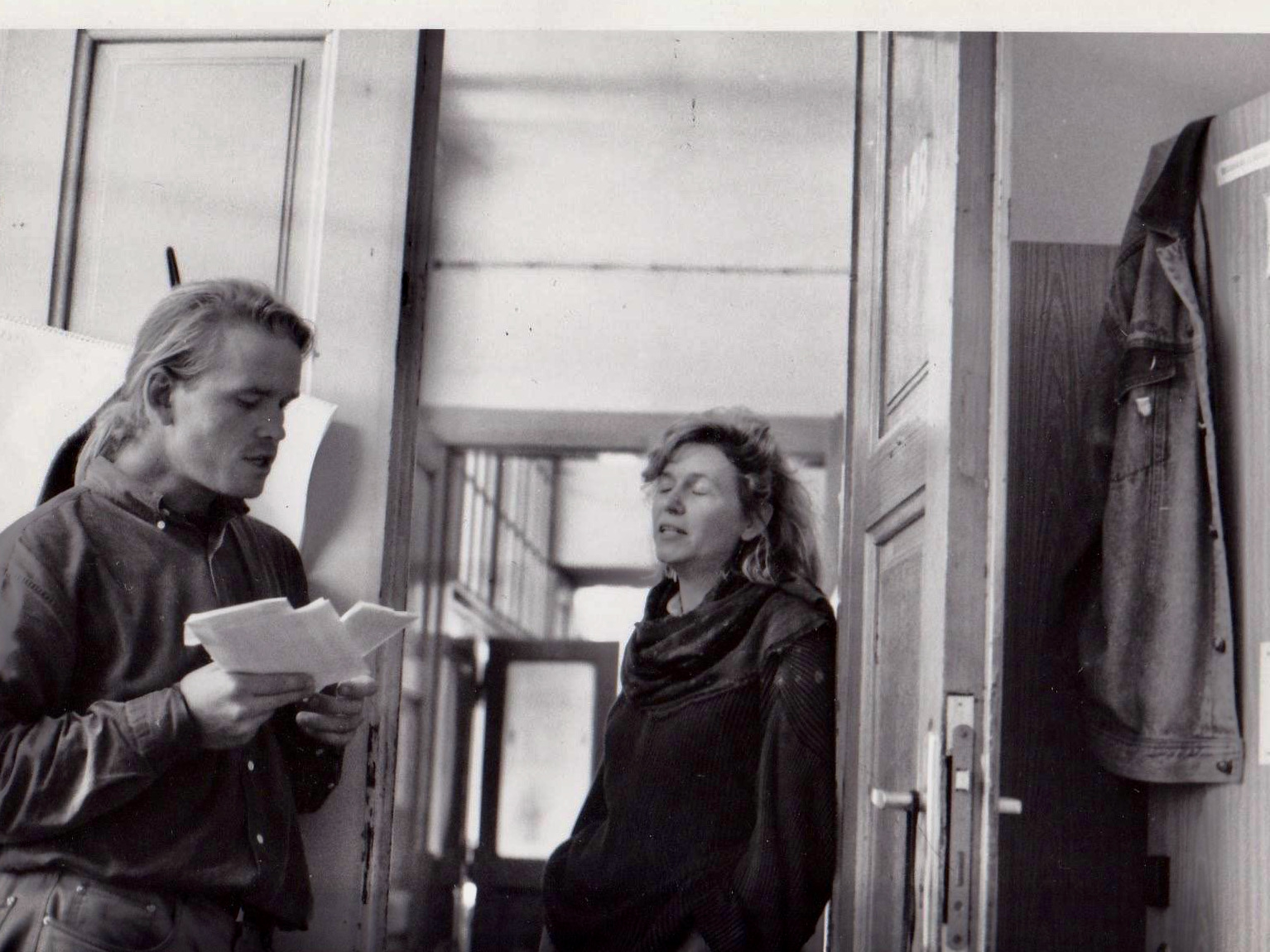

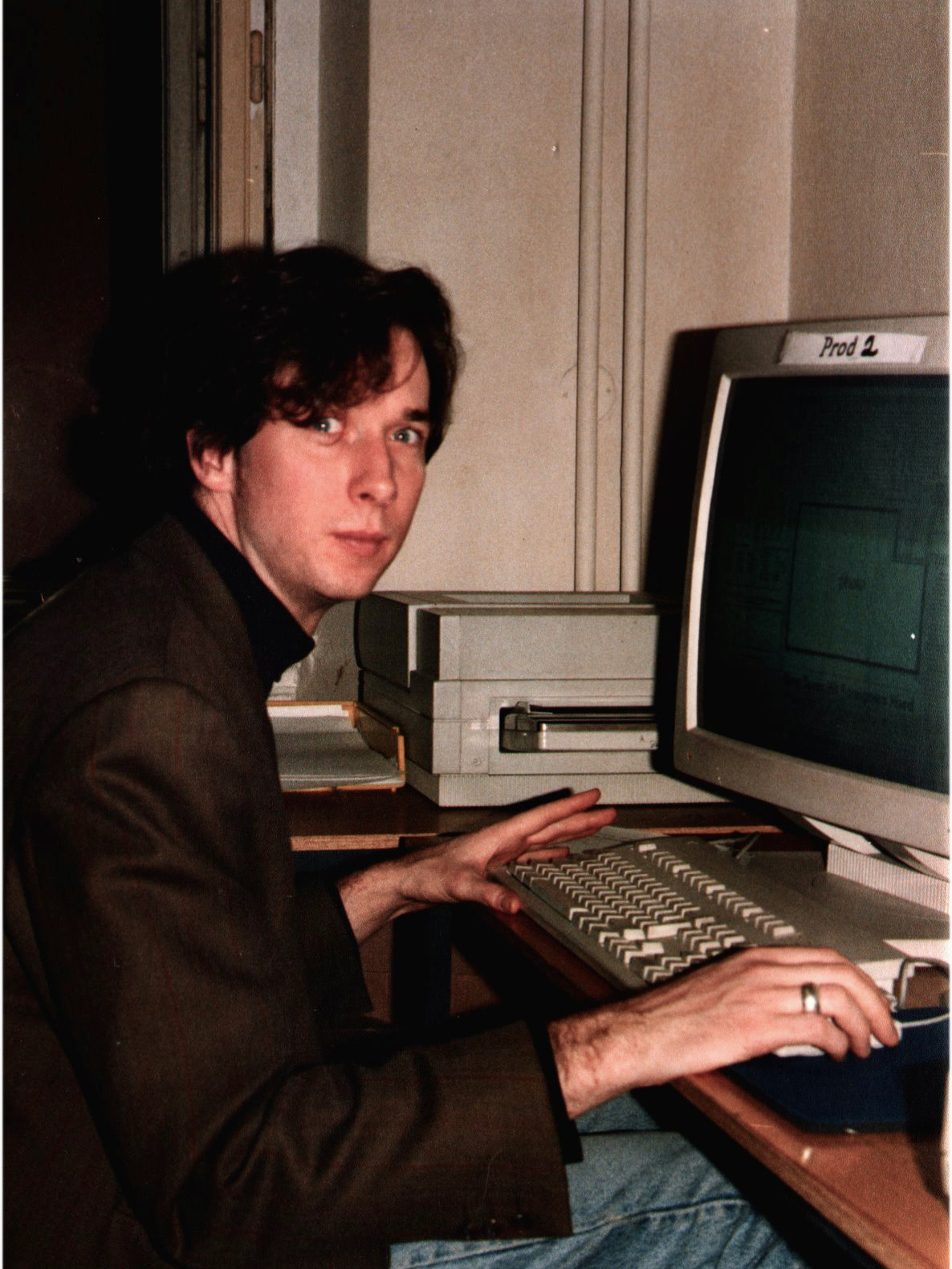

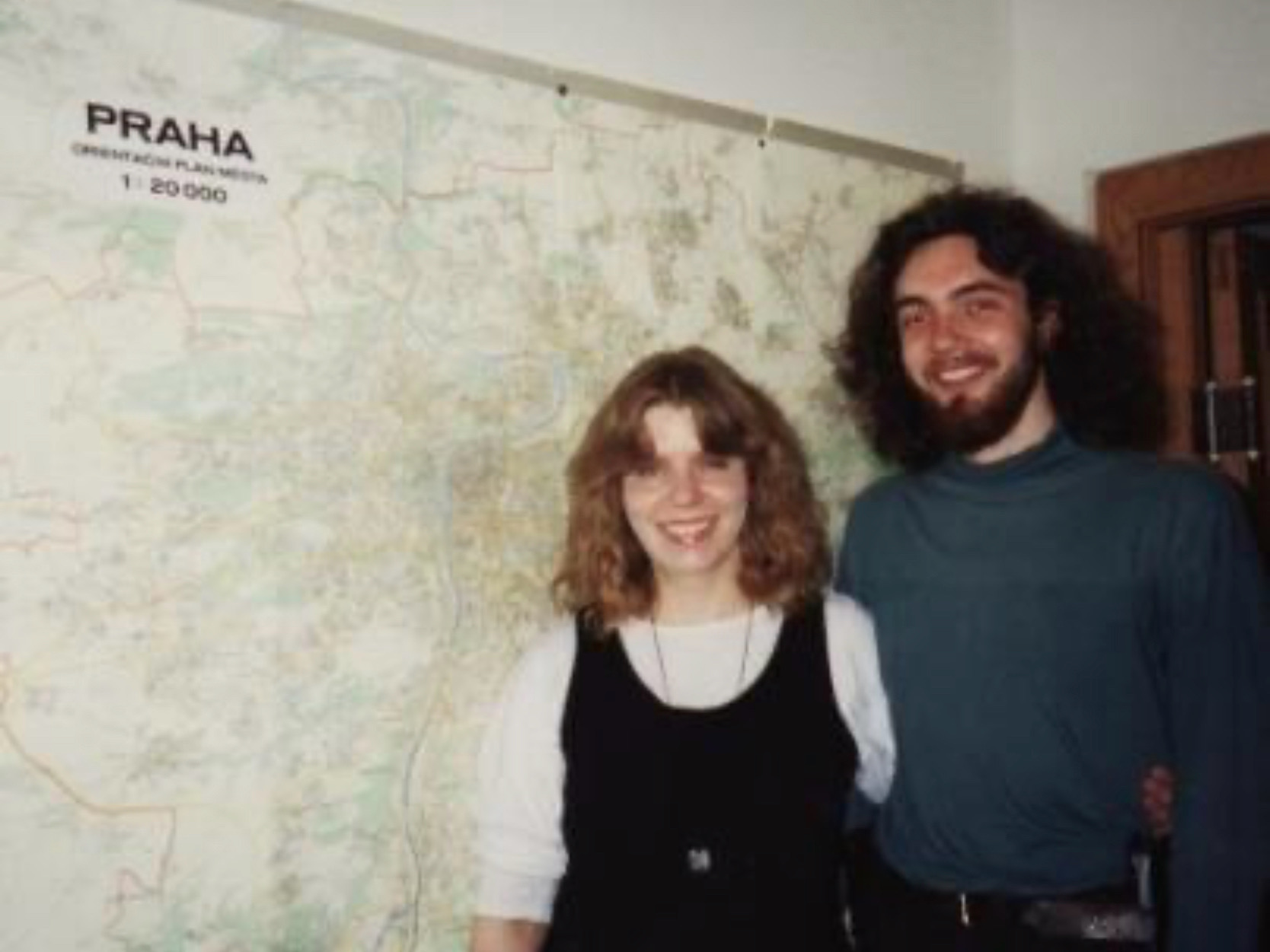

By the time autumn 1992 rolled around, just like Havel I suppose, I too felt burned out. Working at the Post had been exhilarating and covering Czechoslovakia from the inside, instead of observing from afar in Vienna, was satisfying. I met friends for a lifetime at the paper, as we huddled around the back offices at the Communist Party headquarters or at our favorite local pubs and bonded over the stories we covered. But the Post’s rapid turnover in staff, as young reporters came and went, and the unending flow of major – and mainly depressing – news stories had worn me down.

Outside the windows of our busy newsroom – and away from the then-gloomy corridors of Prague Castle – a far happier transition story was just then unfolding on the city’s streets. Hundreds (and later thousands) of young foreigners were streaming into Prague and, together with an energetic generation of young Czechs, were pursuing their dreams of opening new businesses, bars and restaurants. They were transforming the face of the capital city in front of our eyes. These newcomers appeared to pay no attention at all to the country’s current difficulties and focused their energies, instead, on finishing the job – and furthering the spirit – of the Velvet Revolution. I had my own dreams too: For one, I wanted to open a bookstore. I left the Post on the last day of September 1992 and set my sights on that next step.

_______

From the epilogue:

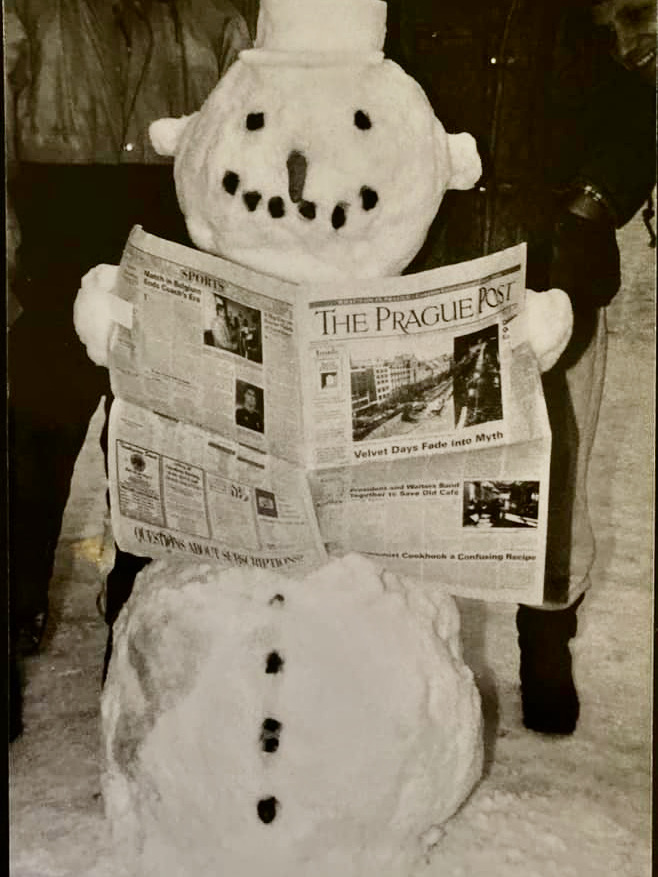

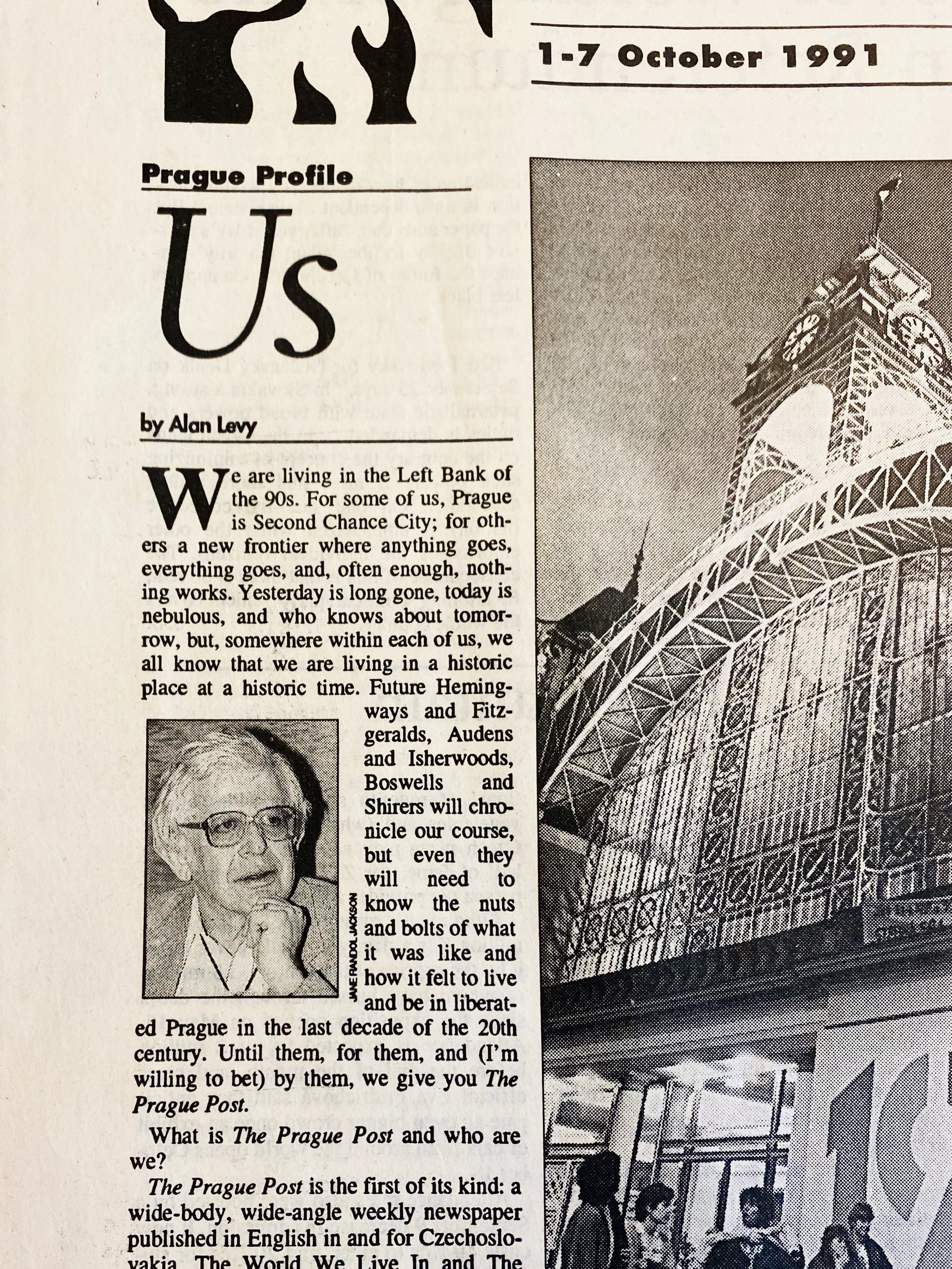

The Prague Post survived into the second decade of the 21st century, long after most of the other English-language publications in Prague from the 1990s ceased to exist. The Post stopped publishing its print edition in 2013 and eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2016. Alan Levy, the paper’s first Editor-in-Chief and the author of the English-language account of the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion, Rowboat to Prague, sadly passed away in 2004 at the age of 72. If the Post and its former editor-in-chief are now gone, though, the paper’s legacy lives on in the continuing work of the many journalists who wrote for the paper and, in some cases, learned the craft of journalism there. This relatively small publication, based in Central Europe, later served as a fertile breeding ground for news organizations around the world, like The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Reuters, Associated Press, Bloomberg and many others.

As of this writing, the paper’s original stories from the 1990s have not yet been fully digitized and remain unavailable through an internet search. That lamentable state of affairs may change soon. Click here to learn about efforts to scan and upload the paper's archives. In the meantime, print copies of all editions are available for researchers and public viewing at the Blue Owl Bohemia library in Loužnice, Czech Republic.

(Scroll past the map to more photos of the paper's early editors and reporters enjoying some of the more fun moments outside the office.)

Hi Mark, I read your pieces on the Prague Post days a few weeks back. Thanks for posting them. Vadim and I harbor a big fascination with the tumultuous experience of those of you who arrived before or after the Velvet Revolution since we showed up a decade later to a more settled country. Your writing on the Post days was especially fun because we know a number of you! Also, very tangible is the sense of journalistic pressure you all struggled with in trying to get the implications of the country’s dramatic transformation right… I was gobsmacked by the part about Kožený! Looking forward to reading the rest.

Thank you Bonita and very happy you liked the stories!