Sometime around May 1989, according to my file, the StB elevated me from a “possible” candidate for recruitment to a more-active “targeted” recruit. In the parlance of the Czechoslovak secret police, they raised me from an “RS” to an “RT.” This new designation started the ball rolling toward their inevitable operation to lure me in, which played out in the early days of November 1989.

The decision to elevate my status (and green-light the operation) was influenced by several factors (some of which I will never know). These included findings from their own clandestine evaluations of me. Based on these observations, they believed they could exploit my position as an American journalist in Vienna and what they viewed as my personal insecurities (including a weakness for the opposite sex). Their decision was also driven by the challenges facing “Operation OHEŇ” and their desperate need to bring in new personnel to breach the U.S. Embassy in Vienna.

But these were only the initial steps in a longer and much more involved process of vetting and luring me in. Before the StB could approach me, they first had to ensure I was not working for American intelligence. While they couldn't find any evidence of formal espionage training in my behavior, the materials in my file indicate that all the way to the end they were never entirely sure.

One of the biggest problems the Czechoslovaks had in determining my espionage status (and maybe this is a good place to re-assert I was not a spy) was the company I worked for: Business International. Based in Vienna and employing a small team of mostly American and British nationals, BI appeared to the trained eye as a classic front for Western intelligence. Indeed, throughout the 1980s, the communist regimes of the Eastern bloc never seemed entirely sure what the company’s true purpose was. As I wrote last week, in May 1989, the Czechoslovak secret police even sent a formal request to the Soviet Union to ask about BI, but I don’t think they ever got an answer (or at least the answer did not appear in my file).

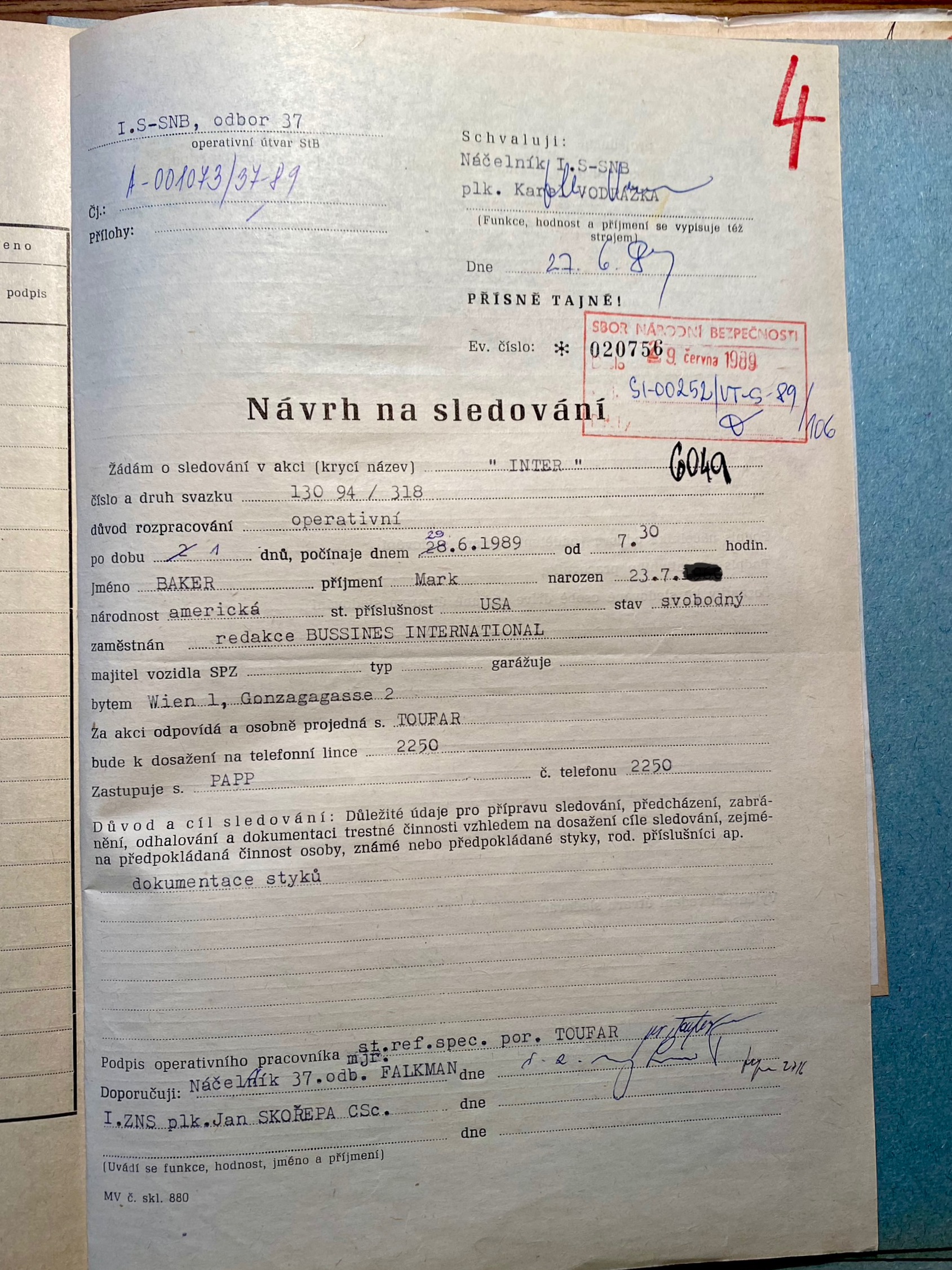

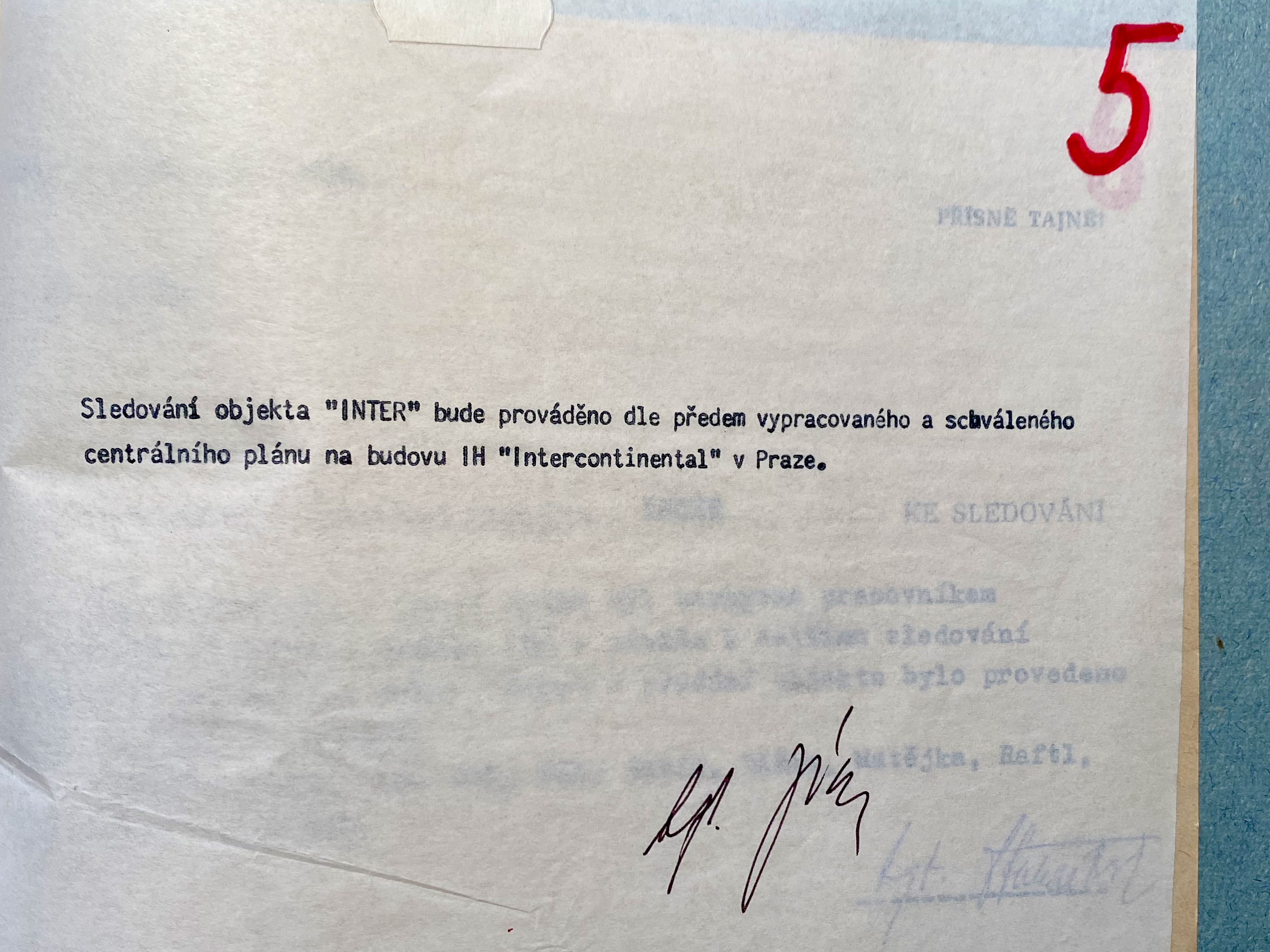

Without a definitive answer either way and not willing to risk any unpleasant surprises, the StB decided in June 1989 to surveil me for a full day without interruption in order to observe all of my behaviors and interactions. Taking advantage of a reporting trip to Czechoslovakia that I planned for later that month, the secret police approved a day-long monitoring operation to take place on June 29, 1989.

Best-Documented Day of My Life

I suppose I should be grateful to the StB. If it hadn’t been for them, the date of June 29, 1989, would have been lost to me for all time. Thanks to their efforts, an utterly hum-drum day in which I met with an executive of Czechoslovakia’s state telecommunications company, lunched with Arnold, and sat down with officials at Czechoslovakia’s Ministry of Foreign Trade, among other activities, is now the best-documented day of my life.

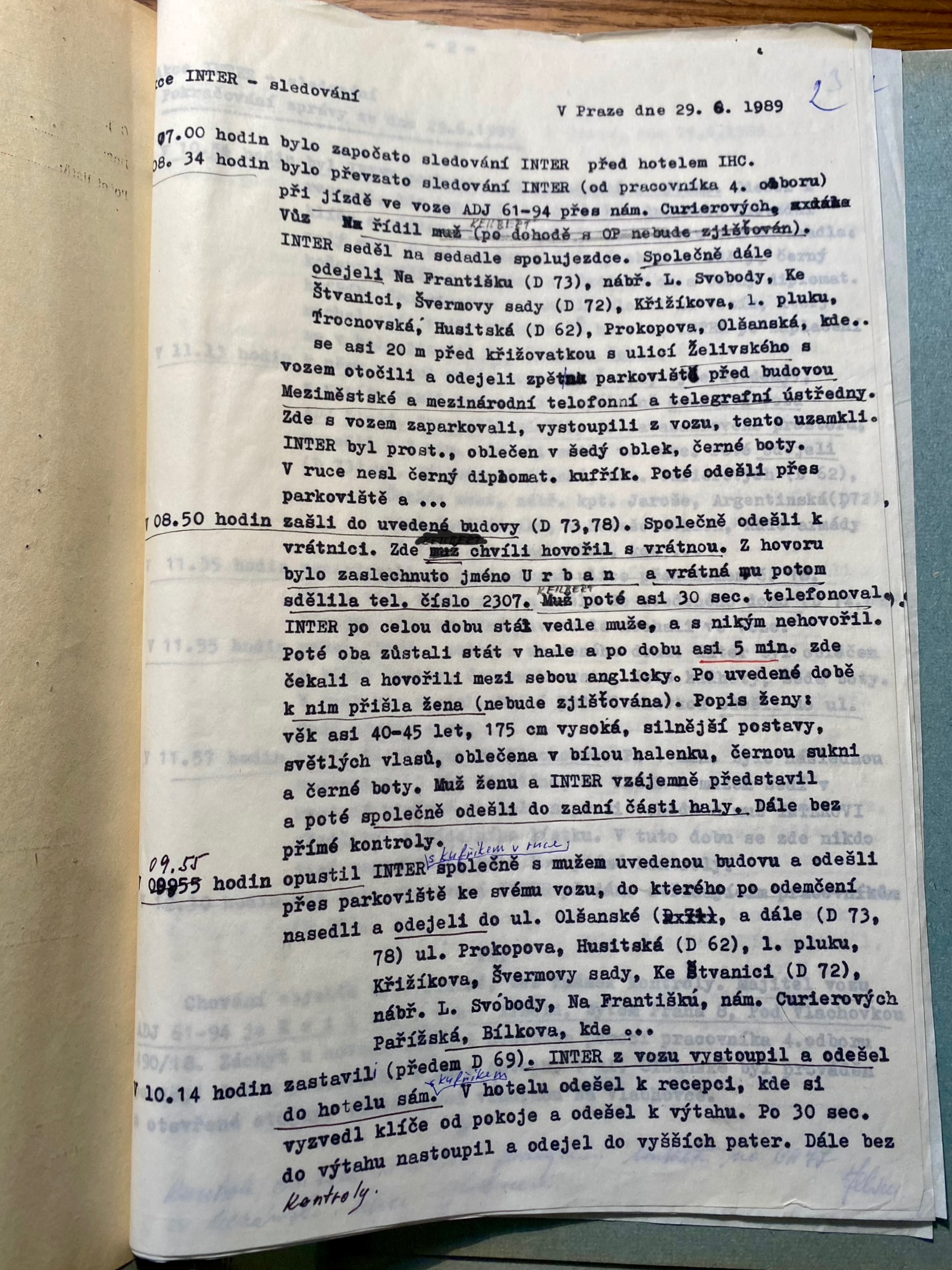

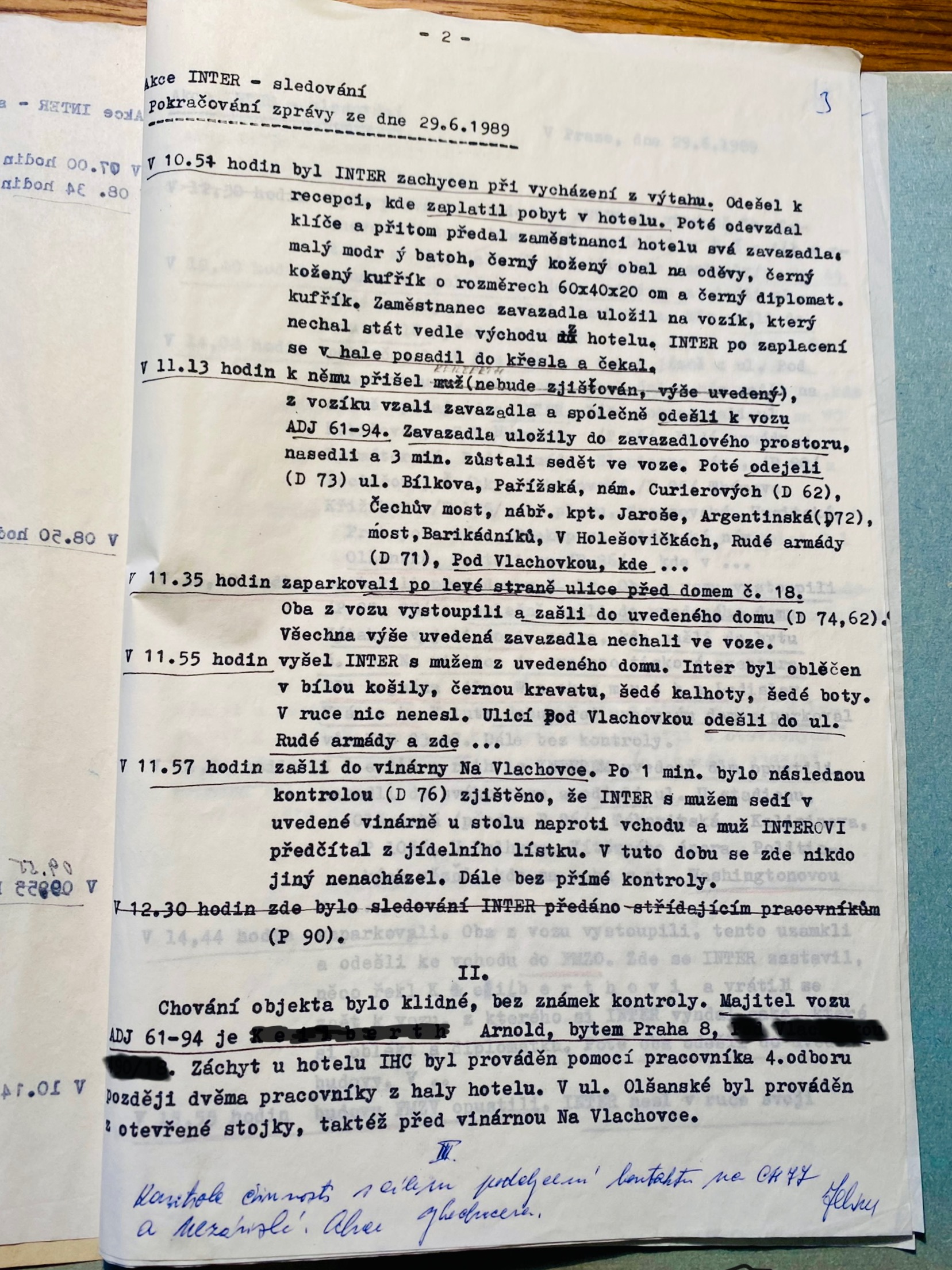

After pouring through reams of material in my file, I now know that surveillance of my hotel room (no. 808) at Prague’s Intercontinental Hotel began precisely at 07:00. I appeared in the lobby at 08:34 dressed “in a gray suit and black shoes … and carrying a black diplomatic briefcase.” At 08:35, I traveled with Arnold in his car to the “International Telephone & Telegraph Exchange” building in the Prague neighborhood of Žižkov. The two of us arrived precisely at 08:50. Arnold briefly spoke to a receptionist and then dialed an internal telephone number ("x2307"). Five minutes later, an unknown woman described as “from 40-45 years of age, 175cm tall, thicker body, fair hair, and dressed in a white blouse, black skirt, and black shoes” approached us and escorted us to her office.

I have almost no recollection of that meeting, but it was probably a routine discussion with a company official to ask about plans they might have to import Western telecoms equipment – information I would then relay to readers of our publications who might be in the business of selling such equipment. To help jog my memory of the meeting, the StB kindly included several clandestine photographs taken of Arnold and me standing in front of the building (a couple of which I’ve posted here).

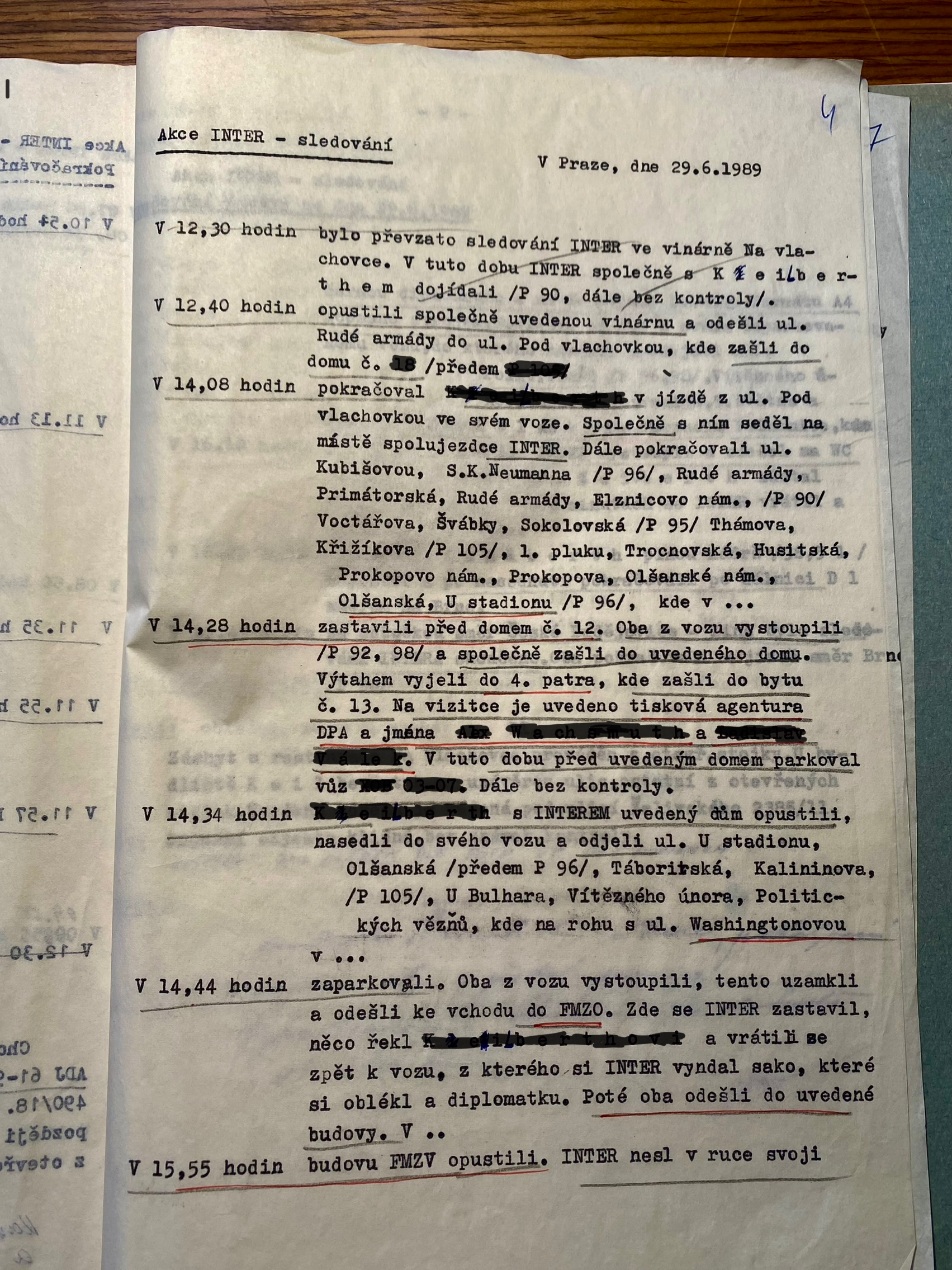

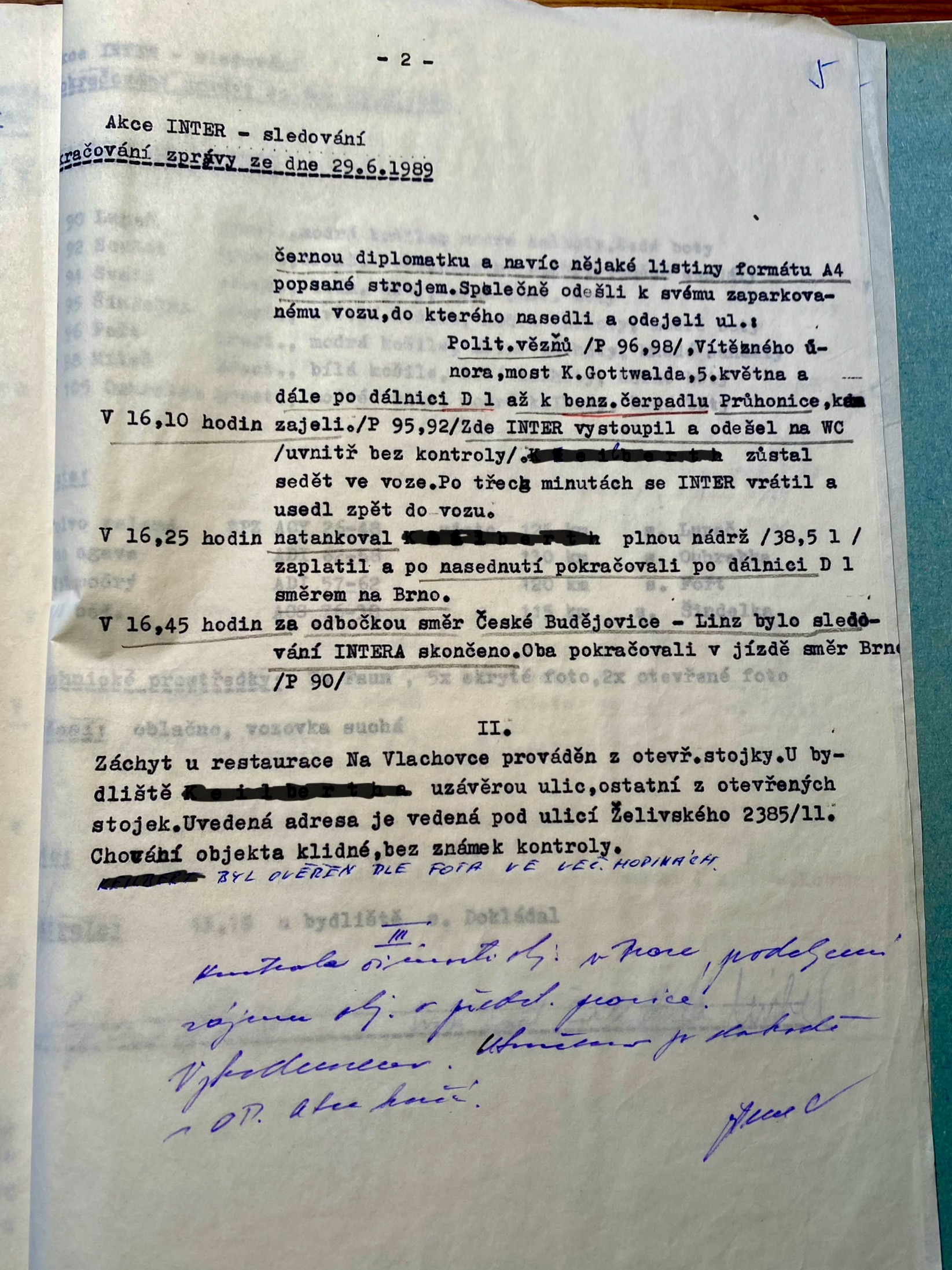

The rest of the operation continued in a similar vein, with the same fine eye for detail, such as the precise times we traveled, descriptions of individuals we met with, and colors and types of the clothing we (and they) were wearing. Presumably, detailed notations of items like jackets or briefcases would have been important as these could be loaded with books or papers and easily swapped along the way. To give readers a flavor of how detailed the surveillance was, I've included a few paragraphs here taken directly from the file (trimmed to improve readability and remove unnecessary personal details). I’m addressed as “INTER” throughout the operation:

At 14:08, [ARNOLD] continued driving his car … INTER was seated in the passenger seat. Further they continued through the streets: Kubišova, S. K. Neumann, Rudé armády, Primátorská, Rudé armády, Voctářova, Švábky, Sokolovská, Thámova, Křižíkova, 1st regiment, Trocnovská, Husitská, Prokopova, Olšanská and U stadionu.

At 14:28, they stopped in front of house no. 12. Both men got out of the car and together entered the mentioned house. They took an elevator to the 4th floor, where they entered apartment no. 13. On a business card is stated a press agency, DPA (German Press Agency), and the names [omitted}. At this time, a car [omitted license plate] was parked in front of the mentioned house.

At 14:34, [ARNOLD] and INTER left the mentioned house, got in their car and went through the streets: U stadionu, Olšanská, Táboritská, Kalininova, U Bulhara, Vítězného února, and Politických vězňů, where on the corner of Washingtonova street they parked.

At 14:44, both individuals got out of the car, locked it, and went to the Federal Ministry of Foreign Trade (FMZO) entrance. Here INTER stopped, said something to [ARNOLD] and they went back to the car, from which INTER took out his jacket that he put on and his briefcase. Then they went into the mentioned building …

I’m not sure what, if anything, the StB got out of this surveillance operation, but maybe it helped to allay fears that I was working as an undercover agent. One page from the file noted the aim of the operation was to spot any contacts I might make with members of the anti-regime “Charter 77 (CH77) or independents." After having observed me so closely, they could see I didn’t make any such contacts. Indeed, I was probably exactly what I claimed to be: a journalist.

A Summer Absence

From the end of June until the beginning of November 1989, my file went quiet. This likely had more to do with events in my personal life rather than any decline in interest on their part. In August 1989, my father unexpectedly passed away of a heart attack. I flew home to the United States immediately on hearing the news and remained there until October. I wasn’t able to return to Czechoslovakia until November 5.

In the months I’d been away from Prague, the geopolitical situation in Central and Eastern Europe had changed considerably. Leaders in Poland and Hungary had taken major steps toward reforming (and even ending) their communist regimes, and the heads of the hard-line Eastern bloc states, including Czechoslovakia, East Germany and Romania, were beginning to panic. In their eyes, the biggest problem was then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Up until the summer of 1989, Gorbachev had tended to remain neutral in adjudicating disputes between the Eastern bloc’s reformers and hardliners. By autumn that year, however, Gorbachev appeared, increasingly, to favor the reformers. This shift would later set the stage for the dramatic, historic events, including the fall of the Berlin Wall and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, that by November were only days away.

Indeed, this widely perceived shift in favor of the reformers is what prompted my early-November reporting trip to Czechoslovakia in the first place. My editors in Vienna wanted to know if the large, anticommunist demonstrations underway in East Berlin might spill over to Czechoslovakia. I would travel to Prague from November 5-8 to report on the political situation in Prague; on November 9, Arnold and I would drive to Bratislava to gauge sentiment in Slovakia. After spending the night in Bratislava, I would return to Vienna on November 10.

And that’s essentially what happened. I traveled up to Prague from Vienna on Sunday, November 5, 1989, and checked into the city's Hotel Paříž (see map below), where Arnold had apparently made my booking. Looking back now, I recall the choice of the Paříž struck me as odd. While it’s an Art Nouveau luxury property now, back in 1989 the Paříž was run-down and a shell of hotel. It was barely a youth hostel, with threadbare rooms and paper-thin walls. I didn’t give it much thought, though (after all, a room is a room). I later learned from my file that the choice of hotel had been quite deliberate and that, this time at least, it wasn’t Arnold who made the booking.

The ‘Perfect’ Reporting Trip

Despite early-November’s typically cold, rainy weather, I had chosen an exhilarating time to travel to Czechoslovakia. While in Prague, I spent my days walking the streets and trying to pick up on signs of political dissent. I would approach people in the street to ask their opinion of the demos in East Berlin and to inquire whether they believed those protests would provoke political change in Czechoslovakia. Most people seemed to be well-apprised of events in East Germany, but the answer they gave me was always a variation of: “No, it could never happen here.”

Indeed, the responses were so resolute that I even wrote a story at the time for BI’s flagship newsletter, “Business Eastern Europe (BEE),” in which I reported that political change in Czechoslovakia wasn’t likely anytime soon. The timing of the story wasn’t exactly ideal. I recall it ran in BEE’s November 20, 1989, edition – just as Czechoslovakia’s anticommunist “Velvet Revolution” was getting underway. Perhaps Arnold's influence over how I perceived events had been stronger than I thought and I interpreted the situation through his eyes. Whatever the case, it was the worst miss of my journalism career.

In the evenings, I and another traveler who happened to be staying at my hotel – an American woman named “Gabrielle” – would walk over to the West German Embassy in the Prague district of Malá Strana to watch the spectacle of thousands of East Germans arriving in the Czech capital to seek asylum and start new lives in West Germany. I can clearly recall the full range of emotions on display -- the hope and tears -- as people stood in long lines in the cold rain to board special buses for the West. (Thinking about that mass exodus now makes it even harder to believe I failed to predict the end of Czechoslovakia’s communist regime – but I was far from the only one to have missed that).

At night, as I tried to sleep, I can still recall the sounds, through the Paříž’s poorly insulated walls, of the garbage trucks on the street below as they emptied trash cans and banged around. The saving grace was the hotel’s signature “Paris" cake (Pařížský dort) that they served in the café. The mix of chocolate cake and custard, covered by a glaze of white icing, might be the best dessert I’ve ever had.

As the Prague leg of the journey drew to a close, I felt the trip was shaping up as a big success. I’d had the opportunity to report my stories, witnessed a piece of history as East Germans streamed westward, ate some excellent cake, and even met a new friend, Gabrielle. Arnold’s presence, always a source of stress on these trips, had been thankfully (and uncharacteristically) low-key.

On the last full day of my stay in Prague, November 8, I had planned to meet up with Gabrielle but realized at the last minute that I wouldn’t be able to make it. To explain the situation, I scribbled out a note to her in which I told her that I had already made plans to meet a friend that evening. I said goodbye and invited her to contact me in Vienna if she ever visited that city. I’m not sure now who the “friend” in the note was, but most probably I’d made plans to have dinner with Arnold.

After writing the note, I folded it in half and gave it to the hotel receptionist to place in Gabrielle’s mailbox. I returned to the Paříž later that evening and saw that she had not collected it. I asked the receptionist to retrieve the message for me and I tossed it away. Early the next morning, I checked out of the hotel, Arnold picked me up in his car, and together we began the long drive down to Bratislava. I scarcely gave the note another thought and forgot about it entirely not long afterward. I never heard from Gabrielle again.

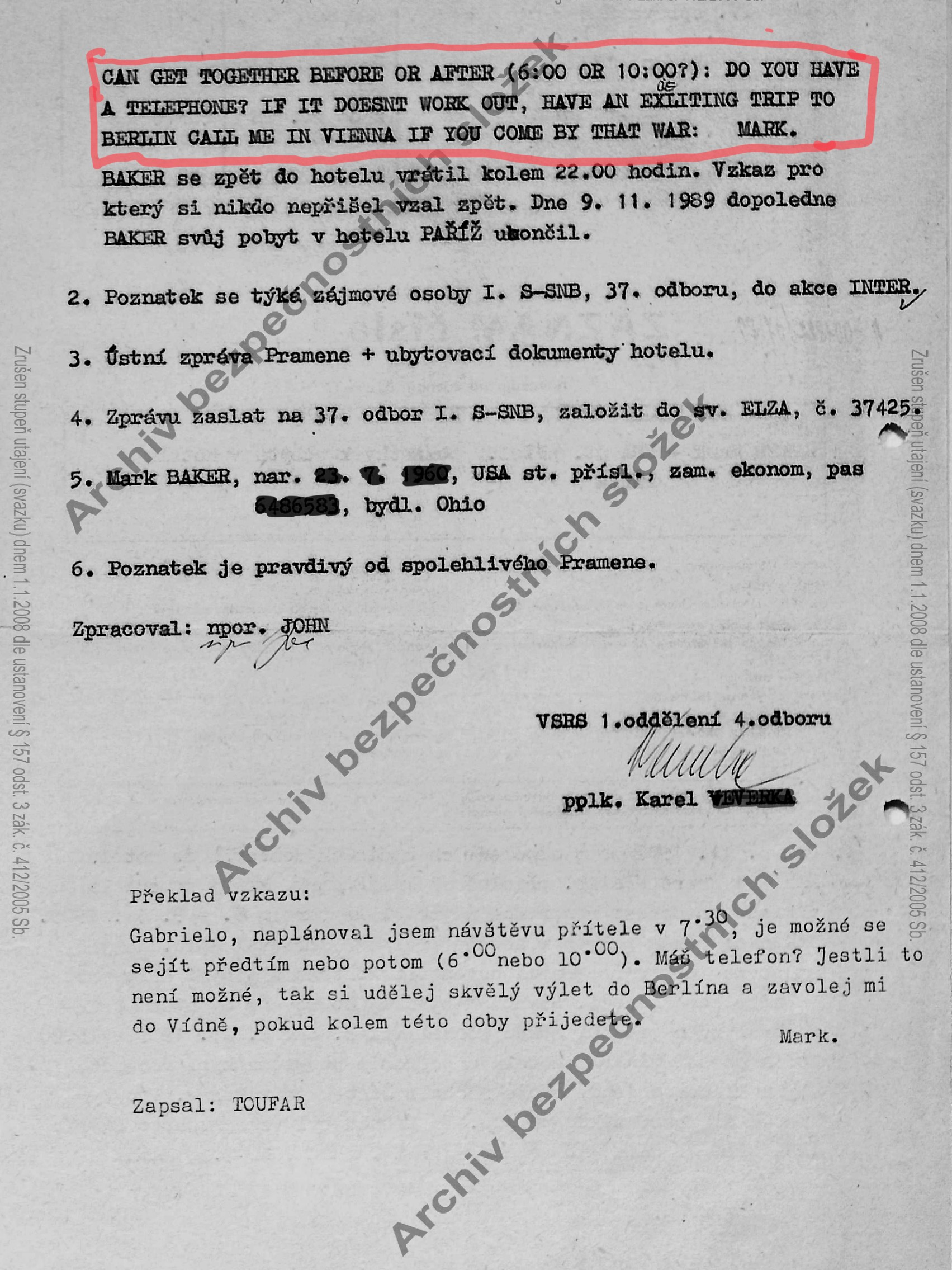

Imagine my shock, then, 30 years later, when over the Christmas 2021 holidays, Dr Tomek sent me the email to let me know about the existence of my StB file. In addition to the spooky-looking surveillance photos of Arnold and me at the top of this post, he attached two photos from a separate surveillance report from the Hotel Paříž during my November 1989 stay. That report had been compiled by a paid StB informant, "ELZA," who worked at the Paříž’s reception desk. Included in ELZA's report was my note to Gabrielle, reproduced word-for-word exactly as I had written it:

“Gabrielle, I have made plans to visit a friend at 7.30pm. Maybe we can get together before or after that (at 6.30pm or 10pm)? Do you have a telephone number? If it doesn’t work out, have an exciting trip to Berlin and call me in Vienna if you come by that way. Mark”

As I read that long-lost note more than three decades later, the hair on the back of my neck stood up.

I didn’t know it at the time, but Operation INTER – the StB’s formal effort to recruit me – was already well underway. Arnold and his associates hadn’t been laying low. They had choreographed every step of the way, and until this point in the story, at least, everything was going according to plan.

(In the last installment, Part 5, I publish more documents pertaining to Operation Inter and divulge the secrets of what went down on the night of November 9 in Bratislava’s Hotel Devín. Click here to jump directly to Part 5.)

Fascinating and intriguing! A personal account of interesting times in the Eastern Block vs “the West”. You are now an actual part of this history. A story to tell for generations!

Pingback: Travel and Commercial Photographer Susan Seubert 2023 Year in Pictures – Commercial, Editorial and Travel Photographer Susan Seubert

Thank you, Susan!