Karlovy Vary (aka Karlsbad), about 120 kms (70 miles) west of Prague, is a pretty place to visit. It’s filled with classic, opulent 18th- and 19th-century spa-town architecture (see the photos, below) that over the years drew the likes of Russian Tsar Peter the Great, Goethe, Beethoven and even Karl Marx to this little corner of Bohemia.

It’s one of the country’s major tourist draws, and while I’m not really a spa-town kind of guy, I find myself traveling there at least two or three times a year -- to visit the annual Karlovy Vary Film Festival in July, hike around the area, or write about the spa for a travel book or magazine.

On those visits, I have my typical Karlovy Vary routine. I normally spend a few hours walking around, admiring the buildings and sipping the sulfurous spa water that gushes free from the faucets (and usually looking for an emergency bathroom not long after that). I used to enjoy munching on the town’s traditional “Karlsbad” wafers (which mix unusually well with that sulfurous water), but I avoid gluten these days, so anything wafer-like is usually out.

One thing I always do, though, is pay a courtesy call to the Hotel Thermal, a 1960s'-era Brutalist high-rise at the entry to the spa area that hosts the film festival and has evolved into a kind of unofficial symbol of the town. I have lots of memories tied to that place over the years, and despite the hotel’s aggressive appearance, it’s one of the few buildings there I can honestly say I warm to. On my most recent visit, though, in August, the Thermal wasn’t looking very well.

Let’s be clear here, in all the years I’ve been coming to Karlovy Vary and visiting the Thermal, it’s hard to say the hotel ever looked 100 percent well. Czechs often automatically -- and mistakenly -- associate the featureless fronts, rigid lines, and exposed-concrete exteriors of Brutalist buildings exclusively with the former Communist regime and, consequently, treat the buildings with very little respect. (Brutalism, after all, was equally popular, if not more so, in the West.) I’ve made that same faulty association in my own writings, including the Thermal in an essay I wrote on Communist-era hotels earlier this year.

On my trips to Karlovy Vary in the 1990s and early-2000s, the Thermal looked like — well, let’s say it — any other Communist hotel. By that, I mean it was slightly shabby and slightly shady, but at the same time cool in the sense that they’re never going to build buildings like this again. I used to love hanging out in the retro-‘60s lobby, with its red-leatherette chairs and high-top plastic swivels at the diner-like lobby coffee bar. It felt like a throwback to Communist days with a taste of American-inspired mid-century modernism tossed in for fun. It was a time warp wrapped in a time warp, and that’s what made it great.

On my visit in August, a lot of that magic – or whatever you want to call it -- was gone. Maybe I arrived on a slow day, but the lobby was empty. There was a whiff of neglect in the air that extended to the cramped public-restroom area (never the hotel’s strong suit) on the far side of the reception desk. The concrete ramps, walks and parking areas along the outside of the hotel appeared to be crumbling to dust. The southeastern wall, facing the main spa area, was partly boarded up and access cordoned off – though there were no workers to be seen.

Trading notes with Jan and delving into some local news reports for this post, I learned that the hotel stands at a crossroads. A group of developers have won a Czech Finance Ministry tender to reconstruct the hotel. Work was expected to start by the end of the year and run until 2021. The planned investment is around 520 million crowns ($26 million).

That sounds good on paper, but according to Jan and the preservation group he shares with his sister and two others, Respekt Madam, it’s not clear what type of renovation the developers are planning or whether they’ll preserve the building’s unique style and special architectural elements. Karlovy Vary’s spa zone is a protected area, and the investors probably won't be able to make significant changes to the exterior, but the structure's meticulously planned interiors will still be vulnerable. The Ministry of Culture has yet to designate the Hotel Thermal a protected building, which leaves the developers significant scope to do more or less what they want.

For Jan and the many others who care about the Thermal, a stagnating but still largely intact building would be far preferable to an insensitive, characterless renovation.

I can imagine at least some readers might be looking at the photos here of what appears to be a stark and ungainly building and wondering to themselves, “What’s actually worth preserving?” Brutalism poses its own aesthetic challenges and is definitely an acquired taste. I confess I didn’t know much about the hotel either before researching this post. The key to appreciating any Brutalist building, though, is learning more about it. The more you know, the more you want to save. The Thermal, in my opinion, is definitely worth saving.

The building came off the drawing board of Jan and Marie’s grandparents, the vaunted architectural duo of Věra Machoninová & Vladimir Machonin, in the mid-1960s in response to a contest to construct a “festival palace” in the middle of Karlovy Vary. The idea at the time was to preserve the identity of the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, which had come under encroaching competition from the rival Moscow Film Festival. Construction was carried out over around a decade, roughly from 1967 to 1976.

The Machonins were celebrated architects in their day and the authors of some of the most controversial buildings of the time (and which continue to be controversial to the present day). Among their best-known buildings are the Kotva Department Store in central Prague and the former Czechoslovak Embassy building in Berlin. For years, Kotva stood at the center of a hotly contested national debate over whether to preserve or raze buildings built during Communism. In October, the preservationists notched a rare win, and Kotva was declared a protected cultural monument.

The year 1964 – when the Machonins first submitted their proposal – was a period of relative architectural freedom in Czechoslovakia. The Warsaw Pact invasion, and the stifling era of conservatism in arts and politics that followed, was still four years away. Though the couple probably felt some pressure to bend their vision to meet the ideological demands of socialism, they drew extensively from the most forward-looking Western and international styles at the time, like Brutalism.

The basic elements of the design, the long horizontal base, set off against striking verticals, were common features of Brutalist buildings of the late-‘50s and early ‘60s. Google, for example, any photo of London’s Barbican Estate – then regarded as one of the most innovative structures in Europe – to see some obvious similarities (on a much smaller scale). The Thermal would not have looked out of place in any major Western European city at the time.

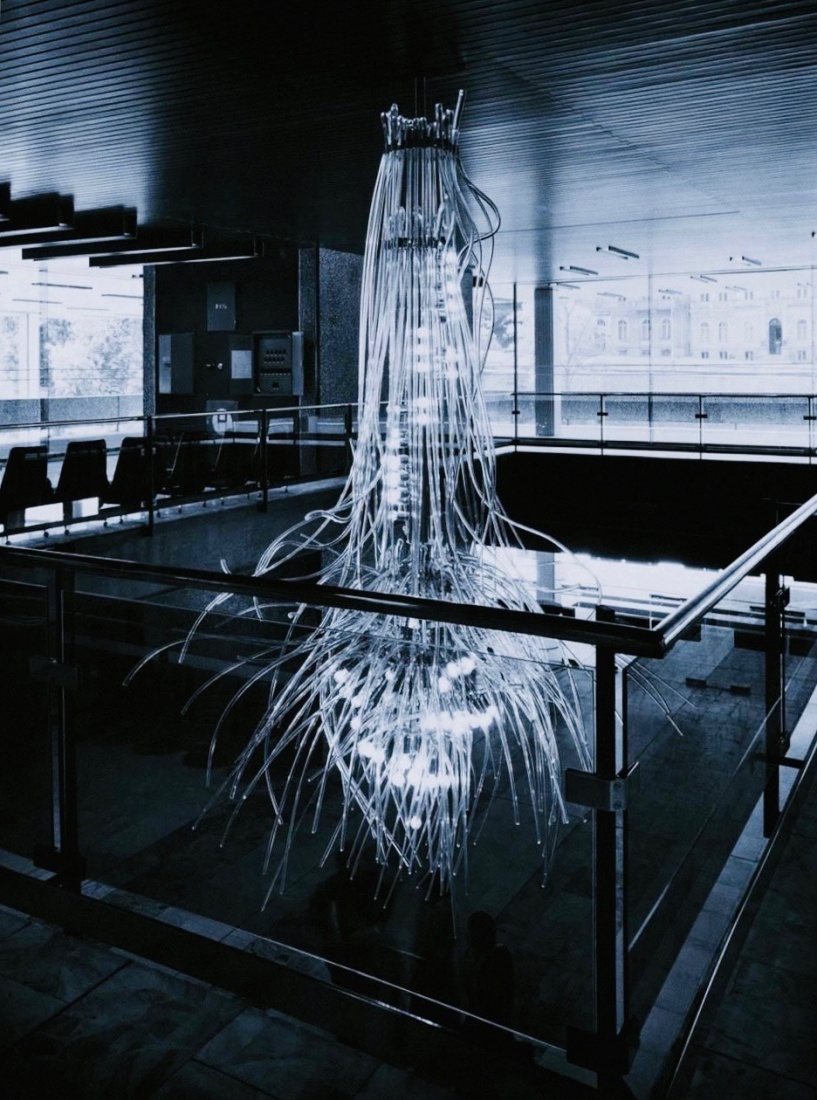

The Machonin’s design, though, was no simple copy of popular international styles. The couple planned the interiors to show off the best Czechoslovak craftsmanship of the day. A list contributors reads like a “Who’s Who” of local design, including the duo of Stanislav Libenský & Jaroslava Brychtová; Miloslav Chlupáč; Slavoj Nejdl; Vlastimil Květenský; René Roubíček; and Čestmír Kafka. Jiří Rathouský, famous for creating the signs used in the Prague metro, designed the orientation system for the Thermal. Many of the artists were later blacklisted after the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968.

Some of those priceless original elements are still there – while others, including much of the funky bespoke furniture designed for the hotel, tragically have now disappeared.

(Scroll down below the map for more photos. For more information on efforts to preserve the Thermal, see the website Respect Madam or contact Jan directly through Twitter).

(I've written frequently in the past on Czech and Czechoslovak architecture. Check out articles here, here and here).

Pingback: Mariánské Lázn? – Part Two — 14° East