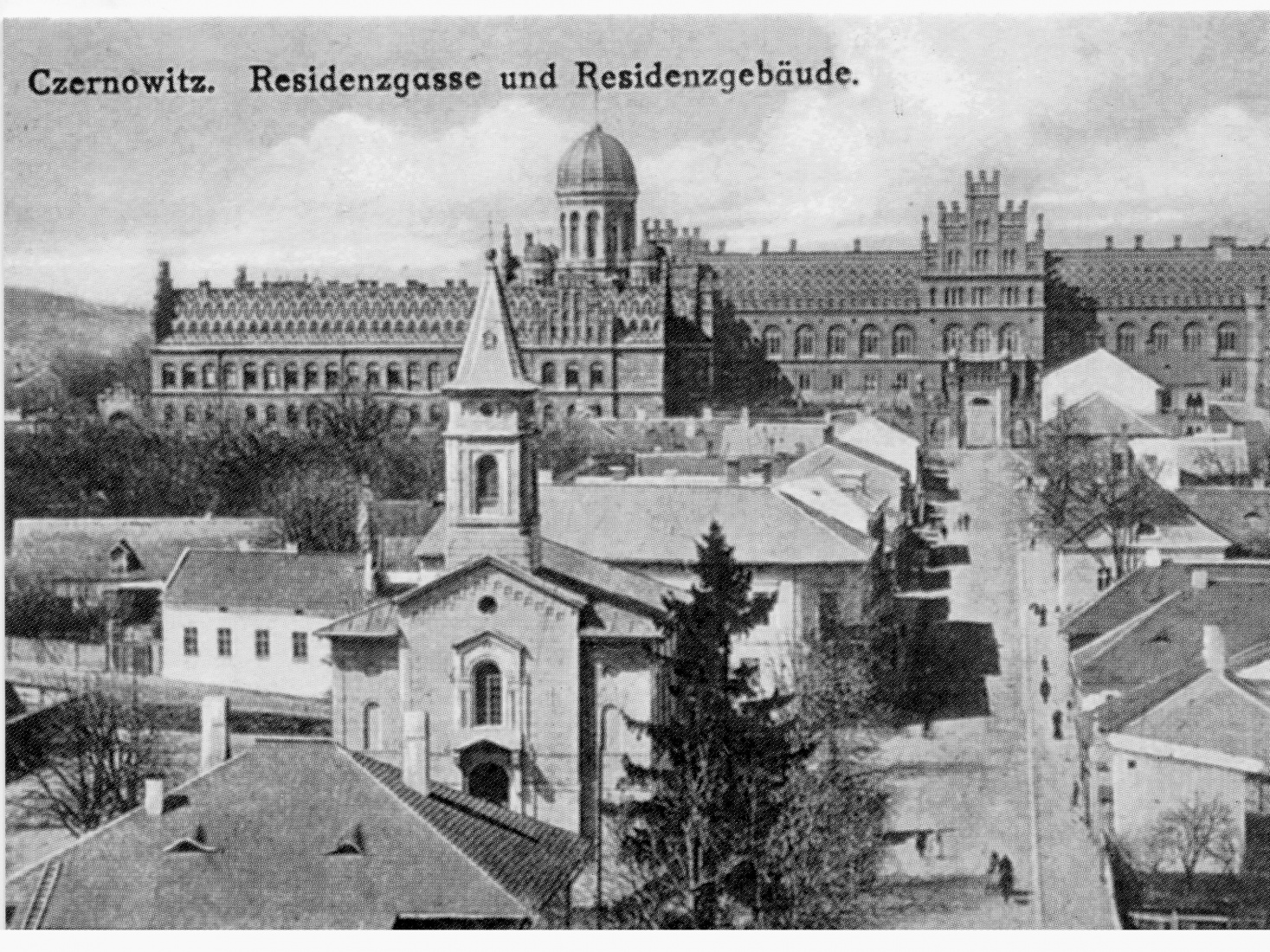

I first heard about Chernivtsi (Czernowitz) in the 1980s when I was living in Vienna. I still have memories of conversations with friends from those days about what a beacon of Viennese civility the city once was in the 19th and early-20th centuries under the old Austrian and Austro-Hungarian empires.

With its diverse, multiethnic population, mixing Ruthenians, Romanians, Poles, Jews and German-speakers, Czernowitz was a microcosm of the empire itself. Austrian Emperor Franz-Joseph I was determined to bestow on the city the trappings of a provincial capital, approving construction of a grand German-speaking university (the Franz-Josephs-Universität) in 1875 and an opulent German theater, designed by the renowned Viennese architectural duo of Fellner and Helmer, in 1905.

Both buildings are still standing, and though they’ve gone through several iterations since those days -- as the city fell under periods of Romanian, Soviet and, now, Ukrainian rule -- they serve as useful reference points for recalling the city’s cultural origins. Emperor Franz-Joseph was obviously marking his turf against possible encroachment of rivals Prussia and Tsarist Russia (and clearly not everything he or the Austrians did was positive), but the scale of both buildings shows the empire’s serious commitment to the city and region. The university complex is especially impressive, the work -- coincidentally -- of a Czech architect, Josef Hlávka, and now a Unesco World Heritage site.

Czernowitz also has some serious linguistic street cred. Romania’s best-known Romantic poet, Mihai Eminescu (1850-89), attended high school in the city, while the famous Romanian-Jewish poet, Paul Celan, was born here in 1920. Celan would go on to lose both parents in the Holocaust to Romanian-run camps in Transnistria, and his most famous work, the “Todesfuge” (Fugue of Death), was an attempt to describe life in an extermination camp through rhythm and imagery. After bouncing around Romania and Vienna after the war, Celan settled in Paris, where his poetry gained a wider audience. Like so many other writers whose lives were indelibly touched by the Holocaust (Tadeusz Borowski and Primo Levi come to mind), Celan eventually committed suicide, in 1970, by throwing himself into the Seine.

Czernowitz was also the birthplace of the Romanian, German-language author Gregor von Rezzori, in 1914. As a grad student in the 1980s, I was a fan of Rezzori’s breakthrough novel in English, the ironically titled “Memoirs of an Anti-Semite.” I used the excuse of my visit this summer to download a copy of the book to my Kindle and give it a quick re-read. I didn’t finish this time around, but the book’s first story, a snapshot of village life near Czernowitz shortly after WWI, just as Bukovina came under Romanian administration, seems to capture perfectly that cautious balance of ethnic, national and cultural sensibilities that governed so much of day-to-day life in the old Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Rezzori, who died in 1998, isn’t discussed much these days, and “Memoirs of an Anti-Semite” appears to have fallen out of favor (the unfortunate title probably keeps it off modern-day college reading lists). In my short re-reading, though, I found Rezzori’s themes to be highly relevant to the modern day. The overarching idea that weaves through much of Rezzori’s work is that it was an unthinking, automatic anti-Semitism that pulled Europe into the abyss in the 20th century. That doesn’t sound so very different from the unthinking, anti-immigrant rhetoric that appears to be pulling us into the abyss this time around.

I mentioned in the intro it was partly my interest in the Holocaust that propelled my trip here this summer. I’ve visited and written about many of the camps and ghettos that the Germans built in Poland during World War II, but I was curious to learn what a Romanian-built Jewish ghetto, like the one the Romanians set up in Czernowitz/Cernăuți in October 1941, would look like.

It’s still not widely acknowledged in Romania to this day (mostly out of a deep national shame), but the Romanian government was a willing participant in the Holocaust, working alongside Nazi Germany in killing Jews and expropriating their property.

There’s not enough space here to write out all the unfortunate reasons this came to pass (and I don’t pretend to be a qualified historian). A short version, though, might go something like this: many Romanians fell under the spell of a right-wing strongman, Ion Antonescu. The Germans, in turn, were highly skilled at exploiting Romania’s long-standing insecurities with respect to Hungary and Russia, and adept at dangling the prospect of acquiring (or at least not losing) historic territories in Transylvania and Bessarabia. The Jews themselves were often demonized as a dangerous fifth column of Bolshevik Russia.

It was this caustic mix that ended up costing the lives of up to 400,000 Jews in Romanian-controlled areas during the war, according to Yad Vashem. The atrocities included the mass murder of Jews living in the provinces of Bessarabia and Bukovina, as well as the killing of thousands of Jews in the Romanian city of Iași and the Romanian-controlled city of Odessa, Ukraine. At least tens of thousands more, like Paul Celan’s parents, died in extermination camps in faraway Transnistria (now nominally part of Moldova).

In Chernivtsi/Cernăuți, the story went as follows: After World War I and the collapse of Austria-Hungary, Chernivtsi and the surrounding territory was awarded to Romania. This wasn’t such a stretch as Romania had longstanding cultural and historic ties dating back to the 14th century; though in the decades immediately after World War I, Romanians made up only a quarter of Chernivtsi’s 112,000 people. Jews constituted the biggest group, at least 27%, according to the 1930 census. Other large groups included Germans, Ukrainians and Poles.

When Nazi-Germany invaded Poland in 1939 to start World War II, the Soviet Union used the invasion as a pretext to expel the Romanians and occupy Chernivtsi. Romania then tragically joined forces with Hitler in 1940. When the Germans attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Nazis and their Romanian allies quickly overran and re-occupied Chernivtsi. The Germans arrived in the city in July 1941 and quickly transferred control back to Romania.

By all accounts, the Romanian administration was a disaster for Chernivtsi’s Jews. Romanians, generally, bent over backwards (at least in the early years) to carry out the anti-Jewish policies of their German allies. They stripped Jewish citizens of their rights and property and quickly drew up plans to concentrate thousands of Jews in a small, sealed ghetto, just north and east of the city center. From there, as in other areas controlled by Nazi Germany and its allies, Jewish prisoners were transferred to exterminations camps. In Chernivtsi’s case, many of the transports went east, to Transnistria.

It’s difficult to find hard facts about the start of the Jewish ghetto in Chernivtsi, but a sealed ghetto was very likely already in operation by October 1941. At its height, the ghetto housed around 50,000 Jews. Many residents died from inhumane conditions inside the ghetto, while thousands of others perished en route to Transnistria or at the death camps themselves.

Amid this unfolding tragedy, there's an Oskar Schindler-like story in Chernivtsi that isn’t widely known outside the city – and might serve as a more positive way to finish up this part of the story.

A handful of Romanians did manage to push back (at least temporarily) against Antonescu’s pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic policies, including Chernivtsi’s Romanian mayor at the time, Traian Popovici. Popovici was opposed to the ghetto and, by all accounts, appalled by the transports and mass killings of Jews. He appealed to Antonescu to save the lives of some 19,000 Jews by arguing that they were integral to the functioning of the local economy.

Popovici was eventually pushed out as mayor and the mass killings restarted. By then, though, it had become increasingly clear to Chernivtsi’s Romanian leaders that Nazi Germany might very well lose the war. Legal sanctions against the Jews were eased in October 1943, and six months later the city was captured by the Soviet Red Army. An estimated 15,000 Jews survived the war, thanks in part to Popovici’s heroic efforts. Like Oskar Schindler, the mayor was later honored by Yad Vashem as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations.”

On my 2019 visit to Chernivtsi, I retraced the steps of the former Jewish ghetto, situated along today’s Sahaidachnoho and Synagogue streets, to look for any surviving remnants of Jewish culture. The first thing I noticed was that, unlike the former ghetto areas of Polish cities like Radom, Częstochowa or Łódź, the Chernivtsi ghetto wasn’t outwardly depressed. In Polish cities, a kind of dark karma still hangs over the old Jewish ghettos all these years later, and it’s often easy to find these places simply by scouting around for the most-destitute neighborhoods. Chernivtsi’s former ghetto looks like any other modest quarter of the city.

Synagogue street was the most crowded part of the old ghetto, and today you can still see the surviving Grand Synagogue (at no. 31) and a view toward the old Jewish hospital (now abandoned) through a gate nearby. The city still has one functioning synagogue, a relatively small, attractive building not far away on Luk'yana Kobylytsi street. The main synagogue, a grand Moorish-Revival building from 1873, is located closer to the center on today’s Universytets'ka St (no. 10). It was damaged in World War II and later converted to a movie theater (“Kinogoga” as it’s sometimes ironically called).

Another surviving building I wanted to see was the former Jewish National House, which stands incongruously next to Emperor Franz Joseph’s grand old German theater, on Teatralne Square (no. 5). There’s a small museum here to Jewish life; otherwise, it's pretty quiet.

The building is best known as the location of a landmark international conference on the Yiddish language, held in 1908, and still viewed as a high-water, cultural moment for Jewish heritage here. As I wandered around the empty halls linking the building’s impressive chambers, I listened for echoes of Yiddish that might still be bouncing off the walls.

I love Romania, and it’s far and away my favorite country in Europe. One thing that always bothers me, though, is what I perceive to be widespread ignorance about the country’s World War II alliance with Nazi Germany and active participation in the Holocaust.

This post was inspired in part by a lunch I had a year ago with a Czech friend who was working at a large multinational company in Prague. She invited me to stop by her company’s cafeteria one day to grab lunch together and chat. And so it was we met, got our food and found an empty table. We began talking and for some reason the conversation wandered over to World War II and the Holocaust. I have no idea how we got to such a dark topic, but it’s a subject we’re both interested in and it seemed natural at the time.

A couple minutes later, one of my friend’s work colleagues, a Romanian woman in her mid-20s, walked over and asked if she could join. The more the merrier, we figured, and we invited to her to take a seat.

We continued the conversation for a couple of minutes, and the Romanian woman chimed in saying she was also interested in World War II. And then she added a couple of sentences that left both me and my friend speechless. She said something to the effect that she was happy Romania was never involved in any of the tragic acts of the war or participated in the Holocaust. “We just didn’t have that many Jews in our country,” she said.

Neither my friend nor I said anything at the time to contradict her. It was supposed to be a pleasant lunch, and the conversation could have become quite heated. Besides, the woman didn’t seem to have any ill intentions; she was simply repeating what she sincerely believed. After an uneasy pause, we changed the subject, but both my friend and I left the table shocked.

Since then, I’ve started to wonder what Romanians actually learn in their schools about World War II and, more generally, how many people are aware of their country’s role in the war and in the Holocaust. Of course, that conversation was simply one incident and it’s never safe to generalize. But the woman was clearly intelligent and well educated. If she believed Romania had nothing to do with the Holocaust, then there are probably many others exactly like her.

I’m not singling out Romania as unique in failing to own up to or acknowledge its historic crimes. As an American, I realize I’m susceptible to more than a little bit of “what about-ism.” What about the slavery of African-Americans? What about the destruction of Native Americans? Every country has its dirty secrets.

My point with this post wasn’t to identify any individual country or people as uniquely bad, but rather to try to promote a broader belief that when it comes to history, transparency isn’t a sign of weakness, but one of strength.

Shortly after publishing this post on Romanian complicity in the Holocaust, I saw on the web an article by The Forward that there are plans afoot to open a Holocaust museum in Bucharest. Find the link to the article here: https://forward.com/culture/433021/holocaust-museum-romania-bucharest-elie-wiesel-institute/

Thanks for this detailed post about a town I hadn’t known about until venturing here. And thanks for the anecdote at the end, which reminds me that education—and the lack of it—forms opinions.

Thank you, Robert, for reading and leaving a comment!

Great article, Mark. I’m happy to have stumbled upon it!

Just wanted to note a couple of things I thought of while reading from the perspective of a historian of Habsburg Bukovina.

A little correction for you: The Jewish National House wasn’t the home the first Yiddish Language Conference in 1908. It seems counter-intuitive but the conference was held in the Ukrainian National House instead! That building is located on the west side of town on Ukraiins’ka vul. 31, across the street from the former Armenian Catholic Cathedral. The likely reason why the conference wasn’t held in the Jewish National House was due to internal Jewish politics at the time. Influential members of the Czernowitz Jewish community wanted Hebrew recognized as the official language of Jews. Therefore, they did not want to host Birnbaum’s conference, the primary purpose of which was to codify and standardize Yiddish as the official Jewish language, and therefore was totally against their own goals.

Second point is more a clarification than an error in regards your photos of the beautiful complex that is now the Chernivtsi National University. When the buildings were completed in 1882, their purpose was not to house the university (which was located down the road) but instead a different kind of “enlightenment.” They served as the Residence of the Orthodox Metropolitan of Bukovina and Dalmatia, which is a little confusing since Dalmatia and Bukovina were on almost opposite sides of the empire! In any case, the buildings and their gardens remained under the control of the Orthodox authorities until 1955, when Soviet Ukraine transferred it to the University (which was also the fate of many iconic buildings in Chernivtsi like the Hotel of the Golden Lion – a favourite among Jews visiting the city).

In any case, your photographs and descriptions are beautiful and I am happy to have found this site. I hope you get another chance to visit Chernivtsi/Czernowitz in the future. The recently restored Jewish cemetery, located on the top of a hill just west of the town centre is impressive in it size. The Jewish community of Chernivtsi began renovating the former pre-burial house and, as of 2018, planned to transform it into a Holocaust museum. In any case, the cemetery is actively maintained and contains the graves of many influential Jewish residents like the first Jewish mayor of Czernowitz, Eduard Reiss (1905-1907); Yiddish poet Eliezer Steinbarg, and deputy of Austrian parliament Benno Straucher, to name but a few. The cemetery also provides anyone visiting with a panoramic view of the entire city, almost as if the former Jewish community is still watching over their old hometown.

Thank you so much for reading the story and helping to make it better. I really appreciate it and will leave your comment here to help future readers. I would indeed love to come back and spend more time. Best, Mark

Thanks for the illuminating article. My mother was born in czernovitz and she spent time in that ghetto before the family fled to Bucharest. Interestingly, the Jews of Bucharest like my father escaped deportations by bribing corrupt officials of Anotescu’s government.

It should be common knowledge that Romania is the country that killed the most Jews of any other country except Nazi Germany. They did that on their own as a German ally, without being occupied.

The Romanian Government accepted and acknowledged in 2004 that during WW2 between 280.000 and 380.000 Jews were killed in its own administered territories, especially in Transnistria, Moldova (Bessarabia) and Bukovina (including Cernowitz /Cernauti) and to a much lesser extent in current day Romania.

These facts have been hidden initially during communism by blocking access to (and even destroying) archival material as they were interested in deflecting all the blame onto Nazi Germany.

The extent of those killings was partially unknown by Western countries including Israel and later the subject became partially taboo for political reasons. It was only after the fall of communism that archives was slowly opened and the remaining material started to be accessed. This process is still ongoing and to date most regular people remain unfamiliar with the extent of these murders.

Beautiful Article, my grandfather was from Czernowitz, he Ignacio Pesatty, he was in the army and left romania before the war in the boat Horacio, to Venezuela. Hopefully one day I can visit the city.

Thank you so much for reading and leaving a comment. Mark

Thanks for this article Mark. I am tracing some of my Jewish ancestry and I had relatives from here who survived the war and emigrated to Australia. Your article illuminated some dry and dusty history for me!

Thank you, I am happy you found it helpful. Best, Mark

Thanks for a very interesting article! I have long been interested in the history of European Jews and in recent years have traveled a lot in Poland and the Baltic countries to search for traces of the Holocaust. Last year I visited Lviv for the first time and this year I returned to Ukraine, including to Chernivtsi, where today I walked along the streets of the old ghetto. In the evening, while looking for more information about the ghetto, I came across your article. I am grateful for that. It may become my starting point for further studies on the fate

I’m so happy you find the article to be useful. Good luck on your research. Best, Mark