Before I start in on the list, a couple of caveats: it’s clearly biased in favor of the places I’ve already visited and written about. I’m not comfortable writing about cities I don’t know well or haven’t spent much time in. Secondly, listicles like this are by their nature random. I started this post on a Monday. Had I chosen a different day, I might have compiled an entirely different list. Other cities that merit attention include (in no particular order): Košice, Klaipėda, Subotica, Lublin, Pécs, Szeged, Cluj, Iași, Łódź, Varna, Brașov, at least a half dozen coastal Croatian cities, and lots of others as well. Hopefully, I'll be able to get to these in future posts. I intentionally left Kraków off the list. It’s certainly worth seeing, but as a former Polish capital (that attracts millions of visitors each year), it’s hard to describe it as a second city.

So, here are my choices (in alphabetical order) for a visit once the Covid-19 cloud has finally, fully lifted. Under each, I’ve written a few lines of rambling text to explain what, for me at least, makes the place so memorable.

Burgas, Bulgaria

On a Black Sea coast dominated by bland, purpose-built resorts like “Sunny Beach” and “Golden Sands,” Burgas feels like its own place. The country’s second port, after Varna, just happens to be home to Bulgaria’s biggest naval base and retains the hushed, formal feel of a military town. As a frequent solo traveler, I spend an exorbitant amount of time in my own head, and I appreciate destinations that allow my imagination to wander. Burgas’s lush-looking, remote villas, perched high above the surf, allow for some entertaining invention as I imagine what must have gone on behind those high walls a generation ago, when the country was a loyal member of the Warsaw Pact and Burgas an important military installation. To this day, Burgas attracts loads of Russian visitors, so it’s not at all hard to make those mental leaps.

The city’s long maritime park has plenty of nice beaches and leads, on its far northern end (easily accessible by bike), to a series of salt lakes and mud baths, where bathers splash around in eerily pink-colored water before blackening their bodies in healing mud. Another plus: over the years I’ve been coming here, I’ve never once had a bad meal; that’s something I can’t say for similarly sized cities like Varna and Ruse.

Gdańsk, Poland

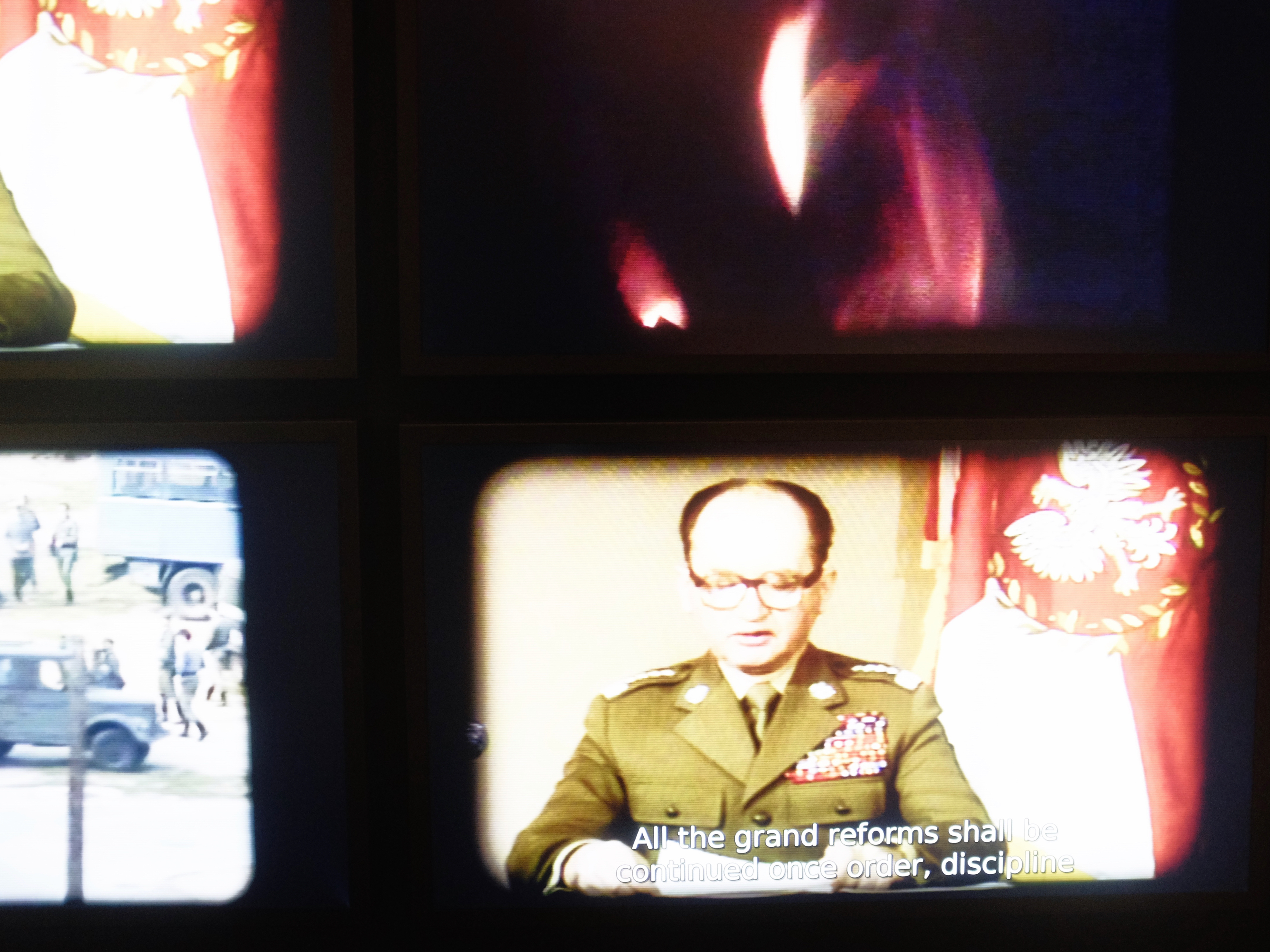

My earliest impressions of Poland’s Baltic port were seared in the 1980s by grainy, black-and-white images of the town and of a shaggy-looking Lech Wałęsa that appeared on the nightly television news or in films like Andrzej Wajda’s influential “Man of Iron.” I certainly felt solidarity with the union, but the city itself, with its giant shipbuilding works and rows of dilapidated public-housing projects, appeared to me as depressingly bleak. A quick trip to Gdańsk over Easter weekend in 1990 cemented that impression. At the time, the city was grimy, the shops and storefronts were still empty.

Imagine my surprise, then, when I returned to Gdańsk in the early 2000s as a travel writer, first for Frommer's and then for Lonely Planet. The dirty Polish factory town was suddenly replaced by a gleaming and prosperous Hanseatic port city. Those old, bleak black-and-white images were thoroughly drowned out by the greens, yellows and golds emanating from the rows of amber shops along Ul Długa, the main street.

During one of those early trips, I happened to book a room in a hotel in the city’s district of Wrzeszcz, where the late German writer Günter Grass had grown up. Indeed, on that trip I felt Grass’s presence everywhere in the city. In more recent years, the city has opened up a high-brow museum, the European Solidarity Centre, to documents the trade union’s crucial role in tossing off communism.

Lviv, Ukraine

I’m not sure why, but it took me years to finally get to the most important city in western Ukraine (and, as Lemberg, the former capital of the Habsburg province of Galicia). I had never managed to wangle a commission to write about Ukraine and only decided to make the detour here during a long, looping private road trip across Eastern Europe in 2019. The obvious comparisons to Kraków, particularly the dominant architectural styles and the graceful, oversized main square, are apt, but Lviv has more going for it than as simply a long-lost sister city.

I loved the flourishing coffee scene, the hidden cafes, the little hole-in-the-wall on the main square dedicated to selling shots of cherry schnapps, Piana Vyshnia (every city needs something like this), and especially the signs of rebirth of Lviv’s once-thriving Jewish community. A tour of the Jakub Glanzer Shul, at the time in the midst of slow-going renovation, was a high-point of my trip. And Lviv proved to be highly affordable. During my stay, I splurged on a room at the elegant Bankhotel, a luxury property fashioned from a 19th century palace that was once owned by an Austro-Hungarian bank. When I got home from the trip and checked my credit-card receipts, I was happy to see the room had set me back well under $100 a night.

Olomouc, Czech Republic

Please forgive yet another reference here to Kraków. I’m not fixated on the place nor am I short on city comparisons. It’s just a quirk of the alphabet that Olomouc follows after Lviv on this list. This former Catholic stronghold, located in the province of Moravia in the northeastern part of the Czech Republic, is a popular day trip for Poles, who (unsurprisingly) refer to the city – and all of its churches -- as “Little Kraków” (so it’s not just me). Like all of the cities on this list, Olomouc’s appeal is multi-faceted. The sacral architecture, including all of the churches but also a Unesco-protected, 18th-century Holy Trinity Column, is surprisingly grand, but Olomouc will also appeal to history buffs and visitors who simply enjoy strolling through parks and imposing places.

Olomouc’s historic bond with Habsburg Vienna was especially tight in the 19th century, when the empire’s emerging middle classes increasingly began to rebel against the monarchy’s outmoded medieval structures. Those grievances boiled over, all around Europe, in the year 1848 – the same year that Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand I chose to abdicate and was succeeded by his nephew, an 18-year-old boy named Franz Joseph. Because of the potential dangers posed by the revolutions, the Austrian royal family had decamped earlier that year to smaller and ever-loyal Olomouc. It was here, hidden within the confines of the Archbishop’s Palace, in December 1848, where Franz Joseph first ascended the throne. The city’s royal secrets don’t end there. Just a couple blocks away from the palace, close to St Wenceslas Cathedral, an early Czech king, Wenceslaus III of Bohemia, was murdered in 1306, shortly after making a fateful decision to invade Poland. The murder remains a cold case to this day.

Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Before I visited Plovdiv for the first time about 12 years ago while on assignment for Frommer’s, I wasn’t sure I wanted to go. I was expecting a medium-sized industrial city in Bulgaria. I mean how interesting could it be? It’s times like these, though, when I’m grateful for the assignments. The city was on a list of places I had to research and I had no choice in the matter. Fast forward to 2021, and Plovdiv could easily make a list of places I’d like live someday – perhaps even ride out my golden years there.

Plovdiv is a schizophrenic place, with two distinct personalities – two sides of the same brain split down the middle by a busy road. One on side, the stately Old Town is stuffed with dignified Bulgarian Revival mansions that show off the extraordinary craftsmanship of 19th century (and earlier) woodcutters, painters, masons and carpet-makers. Many of the mansions have been turned into museums; others house beautiful restaurants, cafes and hotels. On the other side, the arts district of Kapana is like a little slice of San Francisco, with its tiny bakeries, wine bars, cafes and clubs all crammed together. The vibe is so laid back and inviting, you immediately begin wishing you’d planned a longer stay.

Plzeň, Czech Republic

The biggest city in the western part of the Czech Republic is known primarily as the birthplace of modern-style lager – the stuff most people refer to generically as “beer.” It was here, at the local Pilsner Urquell brewery, where “pale lager” was first brewed in 1842. When people today refer to a particular beer as a “pils” or a “pilsner,” this is what they’re talking about. The beer, of course, is still great, and a tour of the brewery is a must-do for beer-lovers. Plzeň, though, is more than its beer.

The attractions include an enormous main square with the country’s tallest church tower. St Bartholomew's Cathedral rises to a height of more than 30 stories (102.6 meters). Plzeň is also home to the second-biggest synagogue on the European continent: the Great Synagogue, dating from the late 19th century. Last I checked, the building was closed for renovation and is used mostly as a gallery or cultural center. For Americans, Plzeň will have special significance (aside from the beer). Unique among large Czech cities, Plzeň was liberated in World War II by advancing American soldiers, led by U.S. General George S. Patton, and not, as is more typical, by the Soviet Red Army. To this day, residents look back fondly on “the Yanks” and hold an annual liberation festival in early May in their honor to mark the occasion.

A couple of years ago, I learned something about Plzeň I’d never known before: namely, that renowned early-modern architect Adolf Loos had worked in the city in the 1920s and designed several classic apartment interiors. Some of these have been preserved to this day. I was on assignment for “Kinfolk Magazine” at the time and had the chance to tour some of the interiors and write about them (the city tourist office is happy to lead a tour for anyone if you let them know in advance). During one of those tours, I learned of a tragic shooting that had taken place in one of the interiors – further proof that Central Europe is always hiding its secrets. I wrote about that tragic event for my blog here.

Ruse, Bulgaria

There’s something about the Danube that appears to deaden the lands on both sides of the river as it separates Romania from Bulgaria on its way to the Black Sea. That riverfront prosperity, so evident in Danube ports like Regensburg or Passau (not to mention capitals like Vienna, Budapest, Bratislava and Belgrade), is nowhere to be seen once the river passes through Serbia and enters into its home stretch to the sea. The Danube is quite literally a backwater in these parts, and maybe that’s part of the appeal of cities like Ruse, Bulgaria’s largest Danubian port.

Of course, the river’s impact over the centuries – when the waterway played a more important commercial and military role – is still very evident. Visitors can tour the remains of a Roman river base, the fortress of Sexaginta Prista, that dates back to Ruse’s Roman founding, under Emperor Vespasian in the first century of the common era. The name translates as “Sixty Ships,” suggesting the presence here of a large and important naval base. The Ottoman Turks, too, left their mark along the river, as did wealthy traders from Austria and other more westerly European countries in the 19th century, when the Danube was finally opened up as an international waterway. Indeed, this 19th-century version of Ruse, with its broad, prosperous-looking boulevards and once-grand mansions, is the one that still greets travelers today. The near lack of any obvious 21st century hustle and bustle (at least in the city center) adds to that time-capsule feel.

Sibiu, Romania

Before World War II and the subsequent communist government the war ushered in, Sibiu and surrounding areas of now-Romanian Transylvania were commonly regarded as “Saxon” land. This was a large swath of mostly German-speaking towns and cities that date back to the 12th century, when the Hungarian kings first invited ethnic Germans to settle here and defend the area against the Ottoman Turks. The aftermath of World War II forced many Germans out of the country, and the German population dwindled further under the rule of Nicolae Ceaușescu in the 1970s and ‘80s. In a bid to earn hard currency, Ceaușescu would routinely “sell” surviving ethnic Germans back to West Germany in exchange for German marks.

Sibiu – or “Hermannstadt” in its German guise – was the center of Saxon land and, to this day, retains the feel of a provincial German town. The main giveaways are the city’s three unspoiled central squares, particularly enormous “Piața Mare” (which, not surprisingly, translates as “Big Square”). Sibiu’s signature, eye-shaped dormer windows, embedded in the tiled roofs of many older buildings, evoke a kind of Grimm’s fairy-tale feel as they silently watch over the comings and goings of city residents.

Sibiu’s fortunes, long in decline even before the tragedies of the 20th century as Transylvania’s governing functions were gradually transferred to the larger city of Cluj, got a boost in 2007 when Sibiu was selected by the European Union to serve as Romania’s first-ever EU Cultural Capital. City fathers made the most of the honorific, assembling an ambitious list of cultural events, including a groundbreaking, open-air concert by the German rock band, The Scorpions, that drew people from all around Romania and put the place firmly back on the travel map. Sibiu holds a special place in my own heart and was the first destination I ever wrote about as a newly minted travel writer in 2007 in an article for the "Wall Street Journal Europe:" “Setting the Stage for Romania’s Revival.”

Timișoara, Romania

The fickle beast of the alphabet is vexing this post once again. Timișoara, like Sibiu, is also a western-Romanian city and even a fellow EU Cultural Capital nominee, though Timișoara’s luck with this designation, so far at least, hasn’t been able to match Sibiu’s. The original plan was for Timișoara to host the cultural capital in 2021 – though that was scotched at the last minute by the Covid-19 pandemic. The date has now been pushed back to 2023 and we can only hope that, by then, international travel will have reverted to something that looks closer to normal.

Timișoara’s charms are more subtle than most of the other places on this list. There are no true “top-level” sights. The draws, instead, for me at least, are the city’s multicultural roots (Romanian, Hungarian and German), close historical links to the Austro-Hungarian monarchy (including lots of local references to the place as “Little Vienna”), a pretty parkland and river system that runs just south of the city center, some handsome modern mansions from the early-20th century (that today house some villa hotels and restaurants), and, of course, a huge university that fuels an ambitious cultural and culinary scene (including a bunch of funky coffeehouses). Timișoara’s main claim to fame, though, at least in modern times, is the role the city played in 1989 in helping to bring down the hated Ceaușescu regime. It may surprise readers to discover that Romania’s anticommunist revolution wasn’t sparked in much-bigger Bucharest, but rather here, in the far western reaches of the country (in a city Ceaușescu apparently detested). In mid-December of that year, a modest, ethnic-Hungarian pastor, László Tőkés, decided to resist the regime’s attempts to sideline him. Within the span of around ten days, Ceaușescu was toppled, captured and executed. You can still see Tőkés’s church and visit a makeshift but highly moving museum to the revolution.

Wrocław, Poland

It wasn’t all that long ago – within the lives of our parents or grandparents – that Poland’s Silesian metropolis of Wrocław was "Breslau," one of the ten largest cities of pre-World War II Germany. When European country maps were redrawn after the war and Poland’s borders shifted hundreds of kilometers to the west, Breslau (once again) became Wrocław. Of course, by that time, Wrocław had long been accustomed to being moved from one empire, kingdom or country to another. As early as the tenth century, in fact, Wrocław – known then as “Vratislavia” – was actually part of the Duchy of Bohemia, before shifting back and forth between some Polish duchies and city-states and even, once again, in the 14th century to the Kingdom of Bohemia. But I digress.

The bigger point with Wrocław (and all the other places on this list) is not so much which country now calls the shots, but rather the complexities and overlays of these various historical and cultural identities and how they present themselves to modern-day travelers. And Wrocław has it all. A beautiful main square lined with stately townhouses, and even dotted with a “Rathaus (Ratusz),” that betray earlier Teutonic origins, but also speak to a shared Central European culture. There are many poignant memorials from World War II, when the Nazis infamously declared Breslau as a “Fortress Town” to be defended to the end, and a pronounced eastern Polish and Ukrainian cultural vibe owing to the period after the war when the city was repopulated by Polish refugees from the east.

Wrocław remains an important university town and has the clubs and bars to prove it. One of my personal favorites, after having lived so long in Prague, is the club “Czeski Film” -- as much for its name as for the place itself. I still find it funny that Poles sometimes use the expression “Czeski film" (Czech film) to describe situations that are absurd to the point of baffling (the way an English speaker might say “it’s Greek to me.”) I like to think of Polish film-goers in the 1960s watching an inscrutable early-Miloš Forman film, let’s say “Fireman’s Ball (Hoří, má panenko),” and scratching their heads in befuddlement. Wrocław, as much of the rest of Central Europe, still remains something of a “Czeski film” for me, and in a very good way.

(Scroll past the map for more photos).

Thank you for this wonderful post!

Just what I have been looking for as I love to explore these kinds of cities. You have now added quite a few to my travelling list. I need another gap year soon, 20 years after the first one 🙂

In addition to your writings I really like the photos and how the whole blog is so delicately put together in terms of colours, font and everything. My favourite sunday read.

Thank you so much for reading and leaving a comment. Very happy to hear you like the blog. Mark