Although Sibiu's recorded history goes back eight centuries, a stroll through the city's broad, handsome squares and neat, cobblestoned alleys, in many ways, feels like a glimpse into Romania's happier future.

The sheer anarchy of a place like Bucharest makes you wonder if the European Union didn't maybe bite off more than it could chew when it took in both Romania and Bulgaria as members in January (2007). The social fabric of the capital seems so ripped apart, you wonder if it can ever be knit back together.

But here in Sibiu, 200 kms (120 miles) northwest of Bucharest, deep in the heart of Transylvania, you sense a social and cultural cohesiveness that immediately feels different and even sparks a glimmer or two of, well, euro-optimism. Maybe it's the anarchy that's the anomaly, and this is the real Romania.

That was probably the hope in Brussels when the Council of Ministers chose Sibiu to co-host, along with Luxembourg, the European Cultural Capital for 2007. At any rate, it was an inspired choice. They couldn't have selected a more Europe-friendly introduction to the EU's newest member state.

Few people will have heard of Sibiu, but for centuries the city -- known by its German name “Hermannstadt” -- played an important role in governing Transylvania, what the Germans called Siebenbürgen to refer to the region's seven fortified towns. German settlers -- or "Saxons" as they are known locally -- were originally brought in by the Hungarian kings in the 12th century to secure the region from Tatar barbarians in the east and were given sweeping trade privileges to support themselves.

By many measures, Sibiu was the most successful of these Saxon-dominated “burgs." The original architects of the town's fortifications -- an elaborate system of walls and towers, many of which are still standing -- were geniuses of medieval warfare. In the 15th century, the town's clannish Saxons repelled wave after wave of attack from the feared Ottoman Turks. Just 100 years later, Sibiu was hailed in travel books of the time as the biggest and most beautiful of the seven mainly-German towns. One account, incredibly, describes it as "only a hint smaller than Vienna,” then the seat of the Hapsburg Empire.

Sibiu's lapse into relative obscurity began in the middle of the 19th century, just as its destiny seemed secure as the seat of Hapsburg-ruled Transylvania. The “Compromise of 1867,” establishing the dual Austrian-Hungarian monarchy, transferred Transylvania to Hungarian control. The Hungarians, in large measure, preferred running their affairs from "Kolozsvár" (the modern-day Romanian city of Cluj), Sibiu's great rival to the north. By the end of the World War I, when Transylvania was ultimately awarded to Romania, Sibiu had dwindled to the status of a prosperous county seat -- essentially what it is today.

The 20th century was not kind to Sibiu's Germans. The Nazis dominated this area in World War II, and many of the ethnic Germans who survived the war were expelled in its aftermath. The rest fell victim to Nicolae Ceaușescu's crushing version of Communism. Many ethnic Germans eventually escaped for the greener pastures of West Germany or were callously bartered by the regime like car parts in exchange for Deutsche marks.

Today's ethnic-German population numbers only about 3,000, though it's the town's undeniable "Saxon" feel that visitors will notice first. The architectural styles -- a fusion of early Gothic with a later overlay of Hapsburg-inspired Baroque and Secession -- the faded pastel colors, and the rough-hewn textures of the walls and roofs all recall something of a prosperous German or Austrian provincial capital.

And the sheer scale of the historic core is shocking. The central Piața Mare, the “Large Square,” is one-and-a-half football fields long and another one wide. Unlike Prague's or Krakow's central squares, this one is largely unadorned in keeping with more modest Saxon tastes, but it provides a perfect, dramatic backdrop to a leisurely stroll on a warm summer evening.

Sibiu's trademark feature has to be those evocative, eye-shaped dormer windows that stare down from ancient rooftops across the city. In the years before 1989, their relentless gaze must have felt more than a little bit sinister -- like the watchful eyes of 1,000 Securitate informers. (This was not such a stretch in the 1980s, when Ceausescu's son Nicu lived here as a kind of village-idiot overlord.) These days the windows' upturned corners appear to be smiling.

For anyone unfamiliar with the European Union's "Cultural Capital" designation, it's one of those quaint bureaucratic honorifics for which Brussels is famous. Each year, the EU Council of Ministers chooses one or two cities to showcase its history as a way of parading Europe's cultural diversity. Competition among the cities is keen, and the Council appears careful not to play favorites.

Judging from past nominees, the process is remarkably democratic. Not surprisingly, cultural heavyweights like Florence ('86) and Paris ('89) have had their day in the sun. But so too have less obvious choices like Glasgow ('90), Thessaloniki ('97), and Cork ('05). There seems to be a conscious and admirable effort to balance out natural beauties like Krakow ('00) with diamonds in the rough like Antwerp ('93).

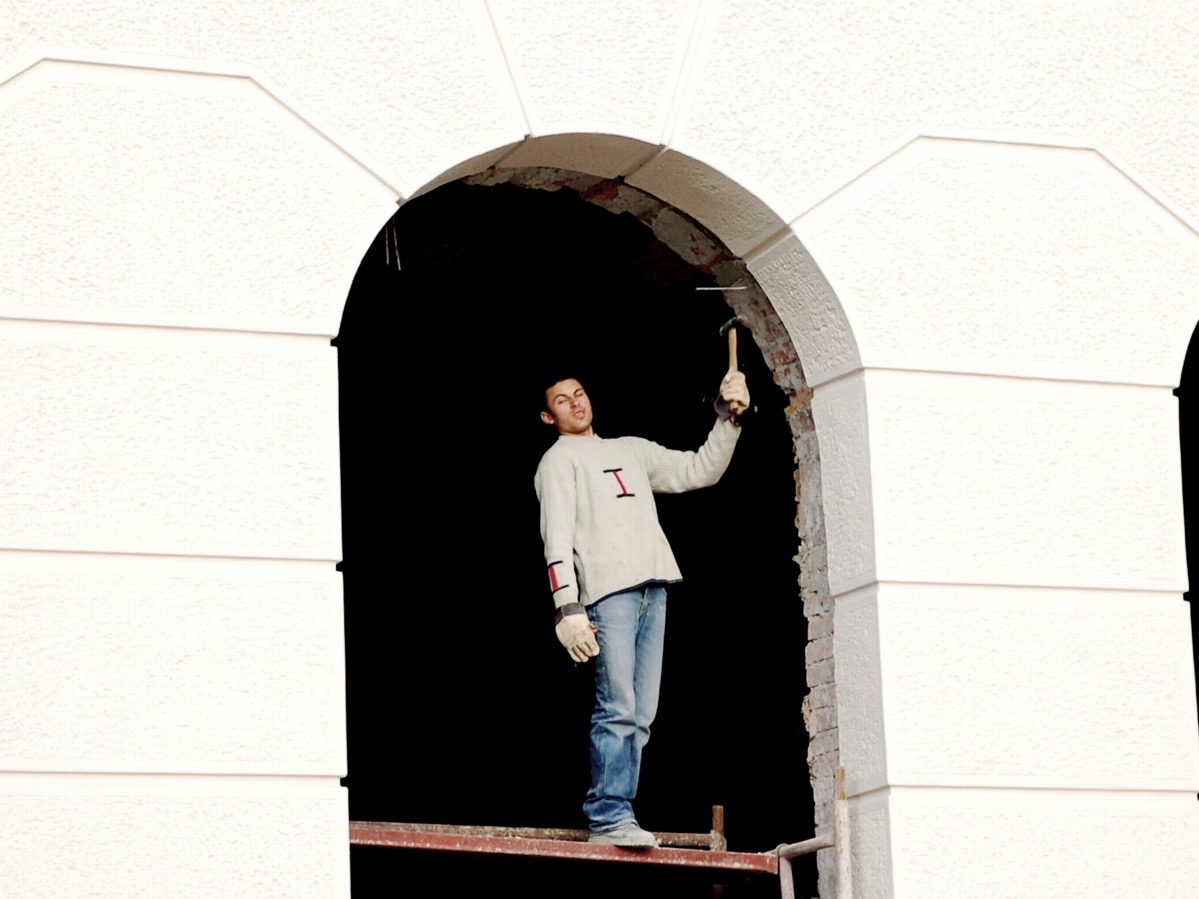

Being a cultural capital is obviously a much bigger deal for smaller cities like Sibiu. Curiously, Brussels doesn't provide any extra funding to the winners, but at the same time, the mere designation alone exerts a kind of "Olympic effect" on the hosts. It's a perfect excuse for city fathers to finally fix up the sewer systems and the streetlights, to paint the facades, and make sure all those glossy "Invest in Our Town" brochures are neatly stacked up at the tourist information office.

The head of Sibiu's Cultural Capital effort, Cristian Radu, is an energetic, young-looking guy, with earnest eyes that stare out through impossibly trendy German- or Italian-made specs. It's his job to coordinate Sibiu's ambitious cultural calendar. That's no easy feat, he says, in a town where people are not traditionally accustomed to working together to achieve common goals.

Radu's days are understandably hectic, but he happily took a few minutes at short notice to sit down with me in 2007 in his shiny offices in the aptly, or oddly, named "Luxembourg House." It's a historic building just off of Sibiu's beautifully restored “Small Square,” the Piața Mica, that by coincidence also happened to house the consular offices of Luxembourg, the other European cultural capital chosen for that year.

Radu quickly dispels any myths about cultural capitals being a kind of gravy train for bureaucrats and host cities. He says not only does Brussels not provide any extra funding to help support the cultural program, they don't even lay down any guidelines for how to run a cultural capital. "There's no 'off the shelf' solution," Radu says.

Radu puts the amount of money Sibiu has spent at something like $100 million -- that's big bucks in a country where a decent salary tops out $10,000 a year, and many people make much less. But he rejects any notion of an Olympic-style boondoggle. He says the Olympics are a "festival" and that's not what Sibiu is holding. He says the money has been spent entirely on projects -- like infrastructure -- in "conjunction with the regeneration of the city." At any rate, Sibiu probably hasn't looked this good since the Compromise of 1867.

Sibiu’s main attractions are clustered around its three main squares -- the Piața Mare (Large Square), Piața Mica (Small Square) and Piața Huet (Huet Square) -- and it’s possible to take in the high points in an afternoon of dedicated strolling. The focus is the pedestrianized Piața Mare, the town’s center for the past 500 years. Just off the square, you’ll find the respected Brukenthal museum, dating from the early 19th century and holding one of the country’s best collections of European and Romanian art. Running the length of the square is a large Baroque Roman Catholic Cathedral and the impressive Council Tower. Scattered in and around all this highbrow masonry are literally dozens of cafes, bars, and restaurants.

Just off the Piața Mare, the much smaller Piața Huet is dominated by the enormous Evangelical Cathedral, a late-Gothic masterpiece that happens to hold the country’s largest pipe organ. Connecting the Piața Huet and the adjoining Piața Mica is a local wrought-iron oddity known as “Liars’ Bridge.” Lore has it anyone telling a lie on the bridge will send it crashing down -- a dubious claim given Romania’s deceptive political culture of recent decades and the fact the bridge is still standing. The Piața Mica is home to the city’s trendiest bars and restaurants, as well as some beautifully restored, arcaded storefronts and, naturally, those smiling rooftop eyelids overlooking it all.

A 10-minute walk to the periphery in nearly any direction brings you to what’s left of the medieval town walls and towers that served the townspeople so well in their struggles against the marauders to the east. The defense plan called for building concentric circles that in the end proved impregnable. Much of this original fortification system is in surprisingly good shape.

Some 6 kms (4 miles) south of Sibiu stands a unique open-air museum, the Astra Museum of Traditional Folk Culture, dedicated to the country’s rural heritage. Here you’ll find miles of handsomely laid-out wooded walks among lakes, streams, and rolling hills, dotted here and there with exhibitions showing the skill and industriousness of the country’s villagers. Come for the education or simply for a few hours respite from the crowded core.

In the end, cultural capitals are about, well, culture. And anyone who braves Romania's dilapidated rail network -- or worse, its roads -- to make the journey here will be rewarded by an uncommonly rich program. In addition to the city's already well-known international theater and jazz festivals, there will be classical music, live theater, performance art, film, and just about everything else throughout the year.

Radu says he's most excited about the late spring and summer offerings. His favorite will be the experimental Brighton-based theater troupe "dreamthinkspeak." Radu says the presence of several thousand-university students gives this old city a very young feel. “Part of the focus is therefore on new media, including electronic music and installation video."

What would those stolid, hardworking Saxons of yore have made of electronic music and installation videos? Not much, probably. But they doubtless would have welcomed the prospect of hosting a European Cultural Capital here as a long overdue step, for the city and the country, toward the European mainstream.

(This story first appeared in print in the ‘Wall Street Journal Europe’ in 2007. I’ve left it more or less how it was written then, and some details here will be unavoidably out of date).

Excellent article. Sibiu is my favourite place in Romania… for the architecture and the history. I visited it first in 1987, long before its restoration. I wish I had more pictures… but I believe we stayed in an old hotel on Pia?a Mare, and the square out front was used as a massive parking lot! (That the toilets wouldn’t flush in the hotel is perhaps part of another story.)

Thank you so much for reading and leaving a comment. I appreciate it.