Oddly, the news article that got me thinking about this Russia thing had little directly to do with Russia’s presence in Prague. It was an article about U.S. politics. To be more specific, it was about Michael Cohen, the personal attorney for U.S. President Donald Trump.

According to the report, by the U.S. news agency McClatchy, Cohen may indeed have visited Prague in the summer of 2016 to meet with some Russian officials – in spite of his strong denials to the contrary. In the past, Cohen has stated categorically he’s never been to Prague in his life (2021 update: Cohen very likely never visited Prague).

I’ll spare you the ins and outs of American politics, but state simply that Cohen’s visit -- if it happened -- would be a big deal. Trump has been very vocal in insisting, since his election in 2016, that his campaign did not collude with Russia. Any confirmation that Cohen, Trump’s personal friend and fixer, had met with some Russians in August of that year -- in a place Cohen denies ever visiting -- would look highly suspicious.

The report said the Prague meeting took place at a Russian-government-owned development agency called Rossotrudnichestvo. I googled around one morning on my laptop in my kitchen and found that Rossotrudnichestvo’s local office was located at the "Russian Center for Science & Culture." The address was Na Zátorce 16, less than 10 minutes on foot from where I was sitting.

If Cohen really had been in Prague, I wanted to see where.

I’m always up for a spy-vs-spy adventure. I grabbed my camera and headed over to the Na Zátorce address, not quite knowing what to expect. Russian institutional names always look so sinister (no matter how innocent the function), and the name “Rossotrudnichestvo” sounded tailor-made as the setting for a secret, high-level meeting.

Though I live close to Na Zátorce street, I don’t spend much time in that part of the neighborhood. It’s a beautiful, tree-lined boulevard of sprawling two- and three-story villas from the 1920s and ‘30s, when Czechoslovakia was a newly independent republic and one of the wealthiest countries in Europe. The street was out of my way, and more importantly out of my price range. I doubt if many Prague residents, even now, know it exists.

I strolled casually down the sidewalk -- my camera slung around my neck -- and pretended to be just another clueless visitor who’d gotten separated from his tour group. I considered carrying a guidebook to complete the picture but figured that might be a bit extreme. My plan was to snap a few surreptitious photos from the street and tail it back home.

When I got to no. 16, though, I was a little surprised. Instead of a spooky-looking villa, hidden behind gates and high hedges, the building that housed Rossotrudnichestvo’s offices looked very much like what it was supposed to be: a cultural center. The building had one of those arty, forward-looking ‘60s facades that all public institutions back then seemed to have. Kids were playing in the yard and a couple bored moms were sitting on a bench outside.

The front door was open, and I popped in to take a look. Toward the back, there was a small coffee counter; on the left, a table where some ladies were holding a bake sale. The walls were covered by some tired-looking displays of Russian scientific achievements. An oversized Russian nesting doll -- a matryoshka doll -- dominated the center of the lobby.

I have to admit I felt a little let down. There wasn’t a stocky guy with a bad haircut or a black, Kremlin-registered “ZiL-111” limo anywhere in sight, and no one seemed to care as I snapped my photos. This was supposed to be the secret meeting place?

I wondered vaguely to myself what Michael Cohen must have made of that giant nesting doll in the lobby.

Even though the Rossotrudnichestvo visit was something of a bust, it got me thinking about Russia and Prague, and particularly about my own neighborhood. If there was a Russian “Center of Science & Culture” here, what other types of buildings or institutions were located on the streets around my house? I really had no idea.

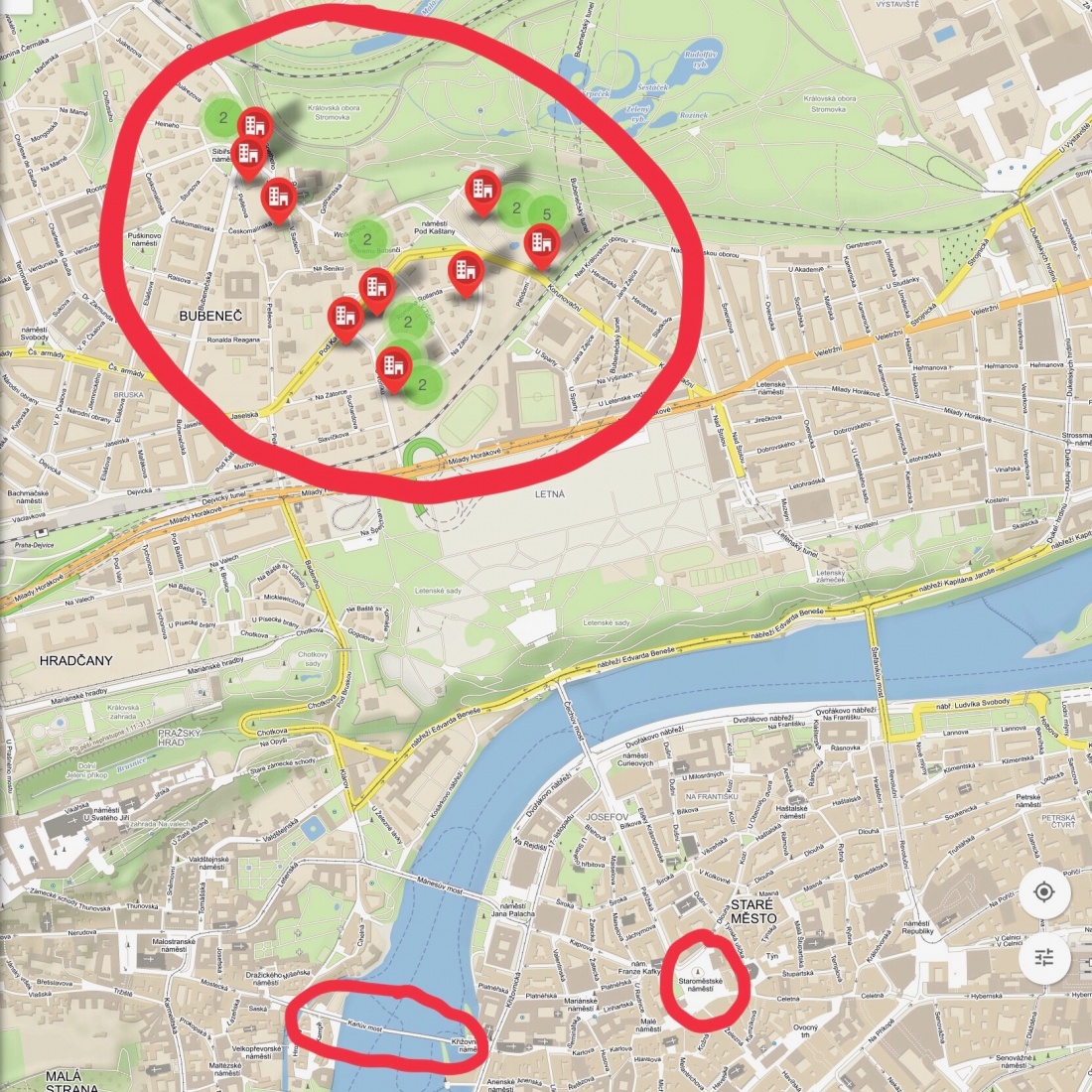

At about this same time, I happened to see an article by the Czech “Institute of Independent Journalism” (Ústav Nezávislé Žurnalistiky) that concerned, coincidentally, the same subject that was on my mind. The article was titled “Prague Bubeneč as Little Moscow” and listed 26 Russian-owned buildings and properties that were located in my neighborhood. It included an interactive map that one could follow at his or her own pace.

The Institute of Independent Journalism is modeled on ProPublica.org in the United States and seeks to promote unbiased investigative reporting. The implicit question behind the article was why Russia would need such a large diplomatic presence, and, going further, whether Russia’s properties were being used to carry out diplomatic functions – or rather to further the private and commercial interests of Russian (or Czech) entities and individuals?

Twenty-six buildings? It was mind-blowing. I had to see this for myself. And so it was on a pretty Saturday afternoon in April (2018) that I loaded the institute’s interactive map on my phone, grabbed my camera, and once again set out for a walk around the block.

And, yeah, the Russians certainly do own some nice real estate here in Prague.

I started my tour of “Russian Bubeneč,” fittingly, at "Siberian Square" (Sibiřské náměstí), just 200 meters from my front door. I pass through this leafy park (it’s not a “square” in the traditional sense) almost every day, though I’d never associated the name with the Russian community before.

Sure enough, according to the map, Siberian Square is an important node of Russian Bubeneč, and the site of a Russian Orthodox Church, the Russian high school, and the headquarters of the Russian Trade Representative. The church, St Ludmila, occupies a striking, circular pavilion once used as a showroom by the trade representative.

The school is larger than it appears from the front and there’s a long-neglected communist-era statue standing on one side. From here, I proceeded behind the school and along Českomalínská street, passing beside a large group of Russian-owned housing complexes. Russia’s holdings are extensive, but by no means are they all luxurious. Several buildings in this area and at another cluster, along K Starému Bubenči street, are simply ordinary Socialist-style apartment blocks like you’d find in any Czech town or city.

From here, I made my way slowly toward the massive Russian embassy complex, about 200 meters southeast of Siberian Square. The embassy’s main building is a hilltop neo-Baroque town palace built in the 1920s for the wealthy Petschek family. The Soviet Union acquired the building at the end of World War II, and after 1991, control of it passed to the Russian Federation. Much of the building remains shrouded in trees and set back behind intimidating fences, but here and there, through the openings, you can glimpse the building’s sheer scale. The sprawling complex, which runs at least a couple hundred meters in length, includes numerous outbuildings, big antennas, and the Russian consular offices.

Na Zátorce street begins just opposite the embassy and runs south for about 300 meters. This street and adjoining Romaina Rollanda street are home to the Russian Federation’s most-prestigious holdings outside the embassy complex itself. These buildings include, in addition to the offices of Rossotrudnichestvo, several breathtaking interwar villas -- one of which, at Na Zátorce 9, once belonged to former Czech President Edvard Beneš.

As I walked along and ticked off the properties on the map, I tried to peek through the windows or look for signs on the houses for clues as to what went on inside. I was surprised to find that some of the villas, including a yellow-brick house at Romaina Rollanda 12 and another brick beauty at Romaina Rollanda 4, looked to be completely abandoned or at least badly underutilized (2021 update: many still appear to be unused).

The few houses that did have signs appeared to support the Institute of Independent Journalism’s contention that, indeed, some (or even many) Russian-owned properties were used for (illegal) private or commercial purposes. I was shocked, for example, to see that the far-right political group, "Hnutí Řád Národa" (Order of the Nation), maintained an office at Edvard Beneš’s former home. Just across the street, at Na Zátorce 12, another Russian-owned villa looked to house the local headquarters of the agricultural firm JZD Slušovice. This may well be the same JZD Slušovice that I wrote about in an earlier post: a shady, Communist-era collective farm that I thought had long been discredited and liquidated.

I finished my tour of "Little Moscow" at picturesque "Pushkin Square" (named for Russian writer Alexander Pushkin) and eventually made my way home. Putting aside all of the diplomatic hanky-panky Russia may be carrying out here in my neighborhood, it should be noted there are some distinct advantages to having lots of Russians all over the place.

I considered stopping by at one of my favorite Russian grocery stores on the way home to pick up some vodka, smoked fish and red caviar. Say what you will, but Russian caviar, at least, is better than the local Czech equivalent.

(Scroll down for more photos of some of the most important Russian-owned buildings in my neighborhood.)

Pingback: Nevíte, kam na výlet? Projd?te se malou Moskvou aneb HlídacíPes.org jako inspirace pro turisty — HlídacíPes.org

Super! Diky 🙂