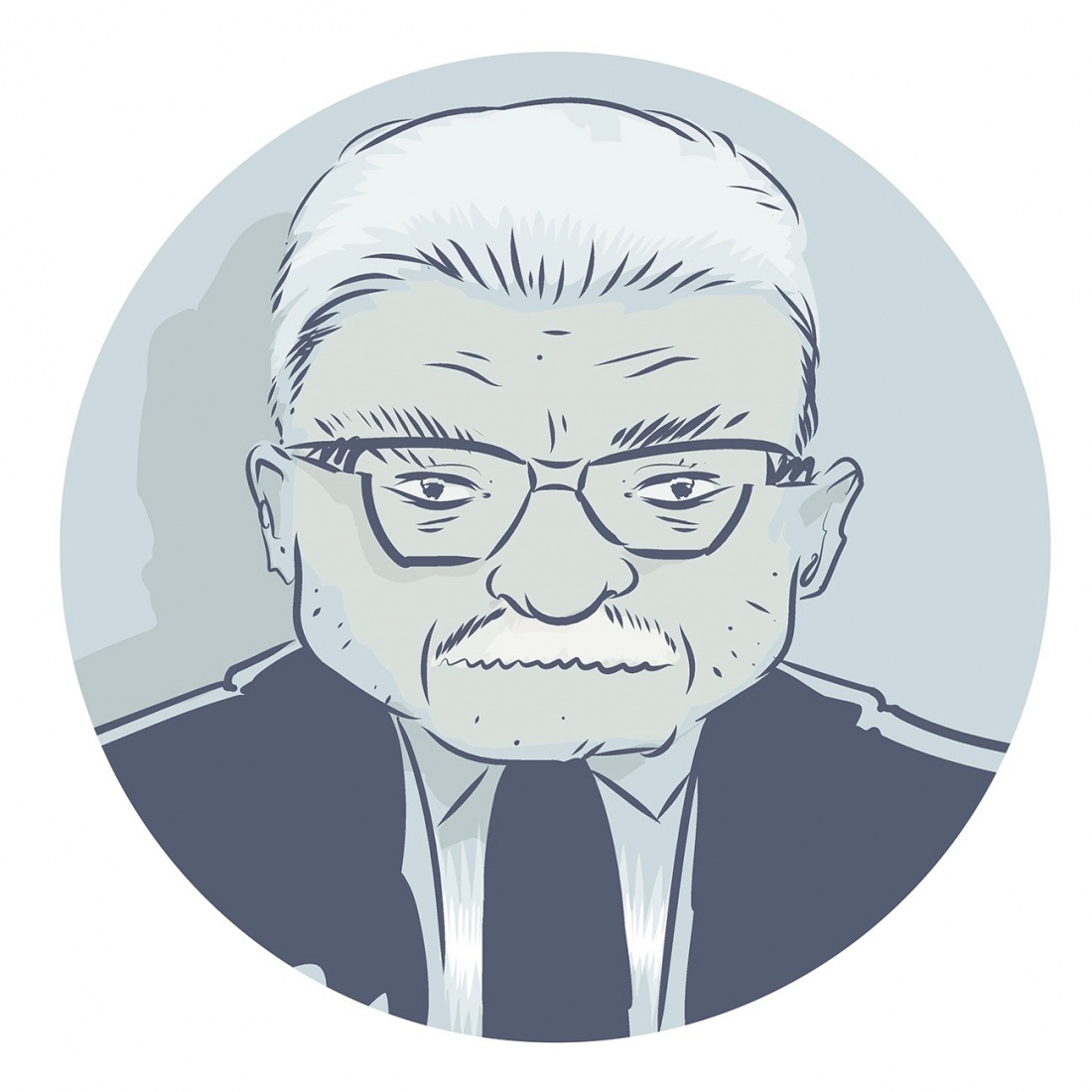

From 1987 to 1989, I made seven or eight working trips from Vienna to somewhere in Czechoslovakia – usually Prague, but occasionally Brno or Bratislava. Each trip was broadly the same. I would alight at the train station (or in the case of Brno, the bus station), walk outside toward the street, and see the stocky frame of my local fixer, Arnold, standing beside a mustard-yellow Škoda 120, shoulders hunched, scowling, puffing on a cigarette.

Those train trips up to Prague were mostly uneventful. The journey was much slower than the four hours it takes now. Back then, the train seemed to have an obligatory, pointless stop at the town of České Velenice, on the Czech-Austrian frontier. The train was almost always empty, and not much would ever happen during these stops. I’d lose myself in thought, staring out the window and watching the station workers come and go. After an hour or so delay, the train would lurch back to life and we’d chug onward.

On a few occasions, though, I’d get a pleasant surprise. I’d spot an attractive woman ambling conspicuously down the train's corridor. (This would only ever happen after we were firmly on Czechoslovak soil.) She’d inevitably open the door to my compartment and ask in Czech if there was a free seat. Trying to be polite, I’d answer “yes” in my poor Czech (the compartment was usually totally empty), and she’d take a seat directly across from me. At some point, we’d make eye contact, she’d flutter her lashes, and the conversation (in English) would start. It was pretty much always the same:

Her: I hear some accent in your Czech. Do you speak English?

Me: Yes, I’m from the United States. I am just visiting Czechoslovakia.

Her: Oh, that’s great. I love the United States. I am trying to practice my English. What state are you from?

Me: blah, blah, blah (and we were off to the races).

The conversation would usually last until the train pulled into Prague’s main station. She’d say goodbye, make some vague promise to meet up, and vanish into the ether -- never to be seen again. I was always amazed at my ability to charm Czech women. I realized in retrospect that she was just doing her job, which was to deliver me to Arnold and ensure I didn’t make contact with anyone or pass on or receive any packages along the way. I didn’t mind, though. The conversations always helped to pass the time.

My trips to Czechoslovakia usually lasted a full week. I’d head up on a Sunday afternoon and stay until the following Friday or Saturday. Arnold would stick to me like glue, picking me up in his car from my hotel for our first meeting in the morning and hanging around until the last after-work beer in the evening. At the time, I didn’t think much about it. I figured he was simply being loyal to our company and making sure I always had a translator or drinking buddy around.

Though I was still in my twenties and Arnold was pushing 60 at the time, we got along well. His daughter was a university student in Austria then (quite a perk for a "disgraced" Communist), so he was up on all the latest news from Vienna. Naturally, I had lots of questions about what was happening at the time in Czechoslovak politics, and Arnold always seemed to make the appropriate noises, voicing guarded criticism of the country's hard-line Communist regime and cautious support for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's reform agenda (though I can't imagine he was too excited about that). I don't remember Arnold having much of a sense of humor, but he was an intelligent man and not bad company. He had a hard look in his eye, though, when he wanted, and that always made me feel uneasy. I didn't quite trust him, but in those days, I depended on him.

His main job during my reporting trips was to set up our official meetings, which were usually snooze fests. At Business International, we covered mainly business and economic topics – and not much in the way of more-interesting political topics. During the week, Arnold and I would normally sit down with the Czechoslovak Minister of Foreign Trade or Minister of Economy, and then pop in to see the heads of the country’s biggest foreign trade organizations. These “FTOs,” as they were then known, were powerful organizations responsible for conducting all of Czechoslovakia’s trade with the outside world. I came to be pretty familiar with the corridors of Chemapol, Strojimport, Technoexport, and many other firms, all with names out of a George Orwell book. They’ve long since been disbanded or broken into smaller pieces and sold into private hands.

The purpose of these meetings was to determine Czechoslovakia’s import plans for the coming year so that I could write about them for Business International’s newsletter “Business Eastern Europe.” Back then, our readers (mostly multinationals like Gillette, Philip Morris, Wrigley’s, Nokia, etc.) relied on our information to plan their sales targets. For example, if the Minister of Foreign Trade told me razor blades would be an import priority, I’d faithfully pass that information back to Gillette and they could organize accordingly.

Looking back on how those meetings usually transpired, however, I’m not sure how well the information we got actually served our readers’ needs. Typically, we’d be ushered into the lush chambers of the minister or head of the FTO and offered a cup of coffee. I’d ask a couple of basic questions to get us started. Arnold would translate these, and then he and our host would gab between themselves for the next hour. I’d try to follow up as best as I could, but I’d inevitably find it difficult to break into their conversation and my mind would start to wander. Arnold would look over at me (probably trying to gauge how much I was grasping) and whisper that he’d fill me in later. What else could I do but nod my head and say okay.

That’s not to say the meetings were entirely unsuccessful. I tried hard to balance my reporting with observable facts on the ground and over the years wrote what I hope were some useful, accurate articles. There’s no denying, though, that Arnold’s role as translator (and ultimately filter for what our sources told us) was highly influential in what appeared in the pages of our newsletter.

Not all of our meetings were these dry, scripted office affairs. We’d occasionally hit the road together in Arnold’s car and pay a visit to a collective farm or state-run enterprise outside of the big city. I liked those days best.

One of my favorite excursions was a road trip in the late spring or early summer of 1989 out to the Agrokombinát Slušovice, a supposedly highly successful cooperative "farm" not far from the eastern city of Zlín (then known as “Gottwaldov,” named after Czechoslovakia’s first Communist leader following WWII).

In the 1970s and ‘80s, Slušovice (see map plot, below) had made some breakthroughs in high-yield crops and pesticides, and had famously expanded its activities well beyond those of a typical collective farm to include running a domestic airline, a test-track for German automobiles, a horse-racing track, and assembling PCs. In 1989, alone, Slušovice reported turnover of something like 7 billion Czech crowns and profits of more than 800 million crowns. Those were unheard of numbers back then.

Even if most of Slušovice's supposed success was fiction, the farm had become a sensation among both Czechoslovakia’s hard-line Communist government and naïve editors of Western newspapers, like the "New York Times." The government was obviously trying to use Slušovice to show the outside world that its rigid, outdated brand of Socialism could work; the editors tended to view the farm through pink-tinted glasses as some kind of futuristic, socialist-capitalist hybrid. I was dying to see it.

Arnold was firmly in his element on that day, proudly introducing me to Slušovice’s directors and showing off all of the farm’s side activities and production areas. As we walked around the dirt lanes and made small talk among the directors, though, I remember feeling somewhat underwhelmed. I was expecting to find an economic beehive; instead, what I saw was essentially just another farm. It was dusty, isolated, and strangely quiet, the type of place where you could hear the flies buzzing in the air. I suspected it was a kind of Potemkin village.

We had a great time that day, though. Potemkin village or not, the guys at Slušovice knew how to throw a party. We had a lavish lunch on the farm, with lots of Moravian wine, and then later that evening, one of the Slušovice directors organized a bash on the terrace of his fancy Gottwaldov apartment. We were in the hands of the gods of that part of the country that night, and even Arnold, who rarely smiled, genuinely seemed to enjoy himself.

That was one of my last official trips to Czechoslovakia and my last work memory of Arnold. Though we didn’t know it at the time, we were just a few months before the November 1989 “Velvet Revolution” that would quickly sweep away that entire world of foreign trade organizations and collective farms. Within a year or two, Slušovice would be broken up, exposed, and mostly discredited. I was in Prague once more that year, in early November, just a couple of weeks before the Velvet Revolution, though I don’t remember spending much time with Arnold. Maybe he, in step with the country, was already moving on as well.

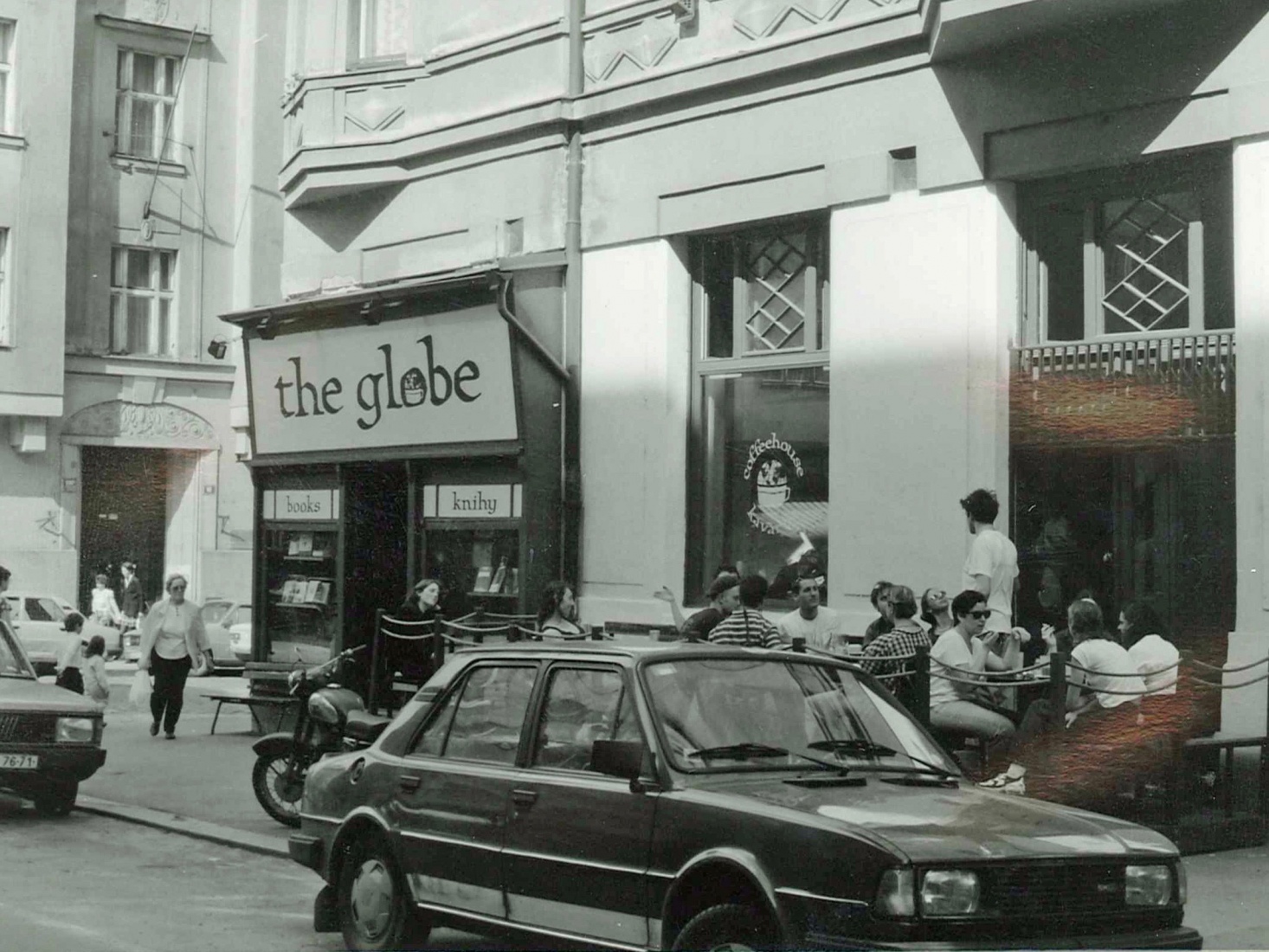

I relocated to Prague permanently two years later, in 1991. Though Prague is a compact city, I only ran into Arnold once in the 1990s. Some friends and I had opened an English-language bookstore, The Globe Bookstore & Coffeehouse, in the Prague district of Holešovice in 1993. One day, Arnold turned up with a film crew from the German TV station ARD to film the "Globe," which was creating quite a sensation at the time. Arnold was translating for the crew, and it was a genuine pleasure to see him again. We caught up on things and said goodbye.

I never saw him again after that, and he and those old days eventually fell out of my day-to-day memory. That is, until one evening a few years ago. I was bored sitting in my apartment, thinking about the past, and googling names on my computer. I wondered what had ever happened to Arnold, and whether he was still alive. I typed his name into the search bar and hit return.

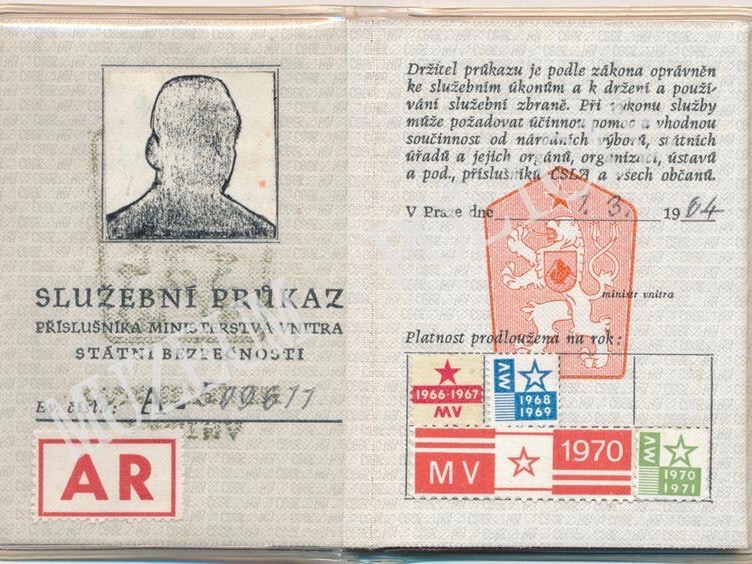

There wasn’t much at first glance. No photos, no Wikipedia entry, no real hits at all. And then my eye caught something. A link to a pdf of a 20-page report published by Prague’s Institute of Military History (Vojenský historický ústav Praha). My old fixer and translator had apparently been hiding some secrets.

(This story concludes in Part 3)