Looking back on the flood twenty years later, my first thought now is the same one I had back then as the disaster was unfolding: How could such a dramatic tragedy – the city’s worst flood in five centuries and a deluge that made the previous epic flood of 1890 look like a mere rainstorm – appear so quickly and without any warning?

After all, the summer of 2002 -- in the days and weeks leading up to the flood – hadn’t been all that different from any other Prague summer. To be sure, there were some bad storms that year, but nothing that felt out of the ordinary. In fact, just a few days before the Vltava peaked, on Saturday August 10, I and my friend Stewart had been caught out in a sudden thunderstorm while cycling around the outskirts of Prague, near the town of Okoř. We waited out the storm underneath a large, low-hanging tree (not the best place to be) in the middle of nowhere, before finally relenting and cycling home in a freezing downpour. At the time, though, I didn’t give it much thought. I knew the weather on a hot, muggy day could turn on a dime (and often did). There was nothing in that storm that screamed “millennial flood.”

In researching this post, I was curious about the storm and went back to some source materials to learn more about it. The rain appears to have been connected to a pair of historically large low-pressure systems -- possibly related to the distant “El Niño” climate phenomenon (the warming of waters in the Pacific Ocean) -- that had cropped up over the Mediterranean Sea. These low-pressure systems drifted northward over the European continent and unleashed storms that initially flooded parts of the Danube basin and then, on the other side of the continental divide, the source waters of Central Europe’s northward-flowing rivers. These included the Vltava, which flows through the center of Prague, and the Elbe, which snakes through Dresden (which was also hit by historic flooding), before emptying into the North Sea, near Hamburg.

Stewart and I didn’t realize it at the time, but as we huddled beneath the tree (and hoped not to die in a lightning strike), we were watching the start of something historic. Of course, neither of us (nor anyone else in town) could have imagined what was coming a couple days later.

I spent most of the next day, Sunday, August 11, lounging around my apartment. Throughout the day, I heard rumors from friends that the river was already dangerously high and that some levees upriver, used to tame and control the river, were under strain. By the evening, the first tentative flood warnings were issued over the radio, though the possibility of a full-on flood – let alone a “once in 500 years” event -- was still viewed by officials as unlikely.

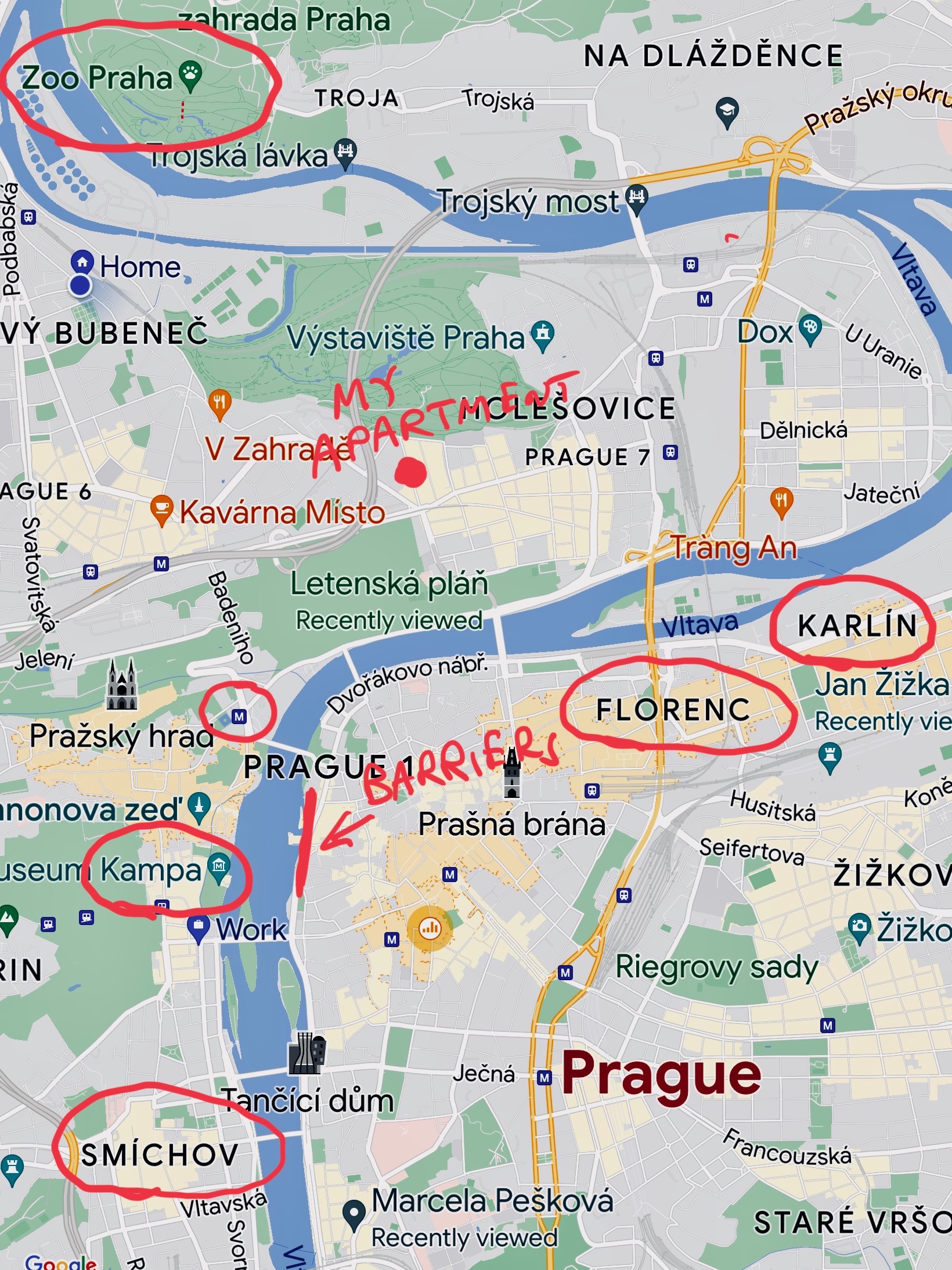

Whatever happened, I knew I wasn’t in any immediate personal danger. At the time, I was living in a higher-elevation part of Bubeneč, just behind the Letná bluff that rises a couple hundred feet above the river. There was no way the water would ever reach my apartment. That said, I glumly contemplated how a flood might affect the availability of clean drinking water or electric power or impact friends living in parts of the city closer to the river.

By the morning of Monday, August 12, the possibility of a serious natural disaster began to feel both more real and more unreal. At the time, I was working for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, though I didn’t go into the office that day. Instead, I spent the early part of the morning glued to the radio, where announcers had amped up their pitch to be more commensurate with an impending deluge. That said, the authorities were still holding out hope the levees closer to Prague would hold and the capital would be spared serious damage.

Later that morning, I grabbed my camera and headed out to points around the city to take the “before” photos that appear in this post. My first destination – and first inclination of just how unreal the moment felt – was Old Town Square. Mid-August is the height of tourist season, and the area below the Astronomical Clock was crowded with visitors craning to get a glimpse of the clock’s medieval mannequins that revolve and turn at the top of the hour. The crowds appeared completely oblivious to the coming catastrophe. Just a hundred meters away from this spectacle, workers were furiously piling up bags of sand along the square’s periphery to protect the historic buildings.

From the square, I walked out along the river’s edge on the Old Town side. It was here, just behind the Four Seasons Hotel, that the banks were lowest along the river’s eastern edge. Workers were furiously throwing up temporary barricades to repel the water if needed. By that time, a light drizzle had begun to fall, though the cobblestones behind the barriers were still dry. I wondered to myself how long they would stay that way.

From there, I made my way over to Malá Strana, a historic district that hugs the river’s western bank. At that time, I was still unfamiliar with the city’s flood topography (and which districts would be most threatened by rising water), but everyone realized that low-lying Malá Strana, and adjoining Kampa Island, would be completely inundated if the levees failed.

Police on this side of the river were already out in force and several streets had been cordoned off to allow emergency workers sufficient space to erect more of those temporary barriers against the rising water. Toward the southern end of Kampa Park, near Říční street, I managed to find a vantage point to take photos (posted here) that would later show just how high the river eventually rose.

At some point, I wandered back home to wait out the news. It may seem hard to believe in retrospect, but many people, even at this late hour, still held out hope that a flood could be averted. Indeed, the city seemed fixated in a state of disbelief. We lacked the collective imagination to envision what was coming.

The Vltava breached its banks sometime in the early morning of Tuesday, August 13. I was asleep at the time (and didn’t hear the sirens) but later learned that at around 4am, officials had ordered residents in lower-lying districts, including Smíchov, Malá Strana, Karlín and Holešovice, to leave their homes and find shelter elsewhere. The water had not only turned the streets into rivers but eroded the foundations of buildings. No structure was safe from sudden collapse.

I spent that day traveling around the city and documenting the damage. The police restricted movement in many places, but I managed to navigate around by sticking to the higher ridges that encircle the central core. The extent of the submerged areas, around 10% of the entire city, was difficult to take in. Whole streets vanished below the river.

Throughout the day, I heard from friends directly affected by the disaster. My RFE/RL colleague, Grant, was forced to evacuate his apartment in Prague’s New Town district. He spent the next couple of nights sleeping on my couch in dry Bubeneč as a flood refugee. Another friend, Brian, was prevented from entering his apartment in Karlín, near the Florenc metro station. That building was later condemned and torn down. A friend in Smíchov had been pulled out of her apartment by the police at daybreak. She ventured back a few days later, only to discover that she’d lost nearly everything, including all of her books and papers.

While the early reports were grim, there were snippets of good news. The 14th-century Charles Bridge, the city’s most important structure and an earlier casualty of that 1890 flood, survived the disaster intact, with only minor damage. Miraculously, the temporary barriers on the Old Town side of the river, tossed up just a day before the flood, had held up. Many streets in the historic core remained dry. This good news was tempered later by reports that 90 percent of the basements in the Old Town had filled with water and several historically important, underground archives had been destroyed. The historic Jewish Quarter, particularly the Pinkas and Old-New synagogues, was also badly damaged.

In the coming days, the full scope of the disaster would become clearer. The most visible casualty was the metro, which had supposedly been built to withstand flood damage. Indeed, the system was thought so secure that some stations were even designated as fallout shelters in the event of a nuclear war. Whether by faulty design or the fact that officials failed to properly close the flood gates, around a third of the stations were inundated. Low-lying Malostranská station, in Malá Strana, found itself temporarily at the bottom of a pond.

The high water also tragically touched parts of the Prague Zoo, in the northern district of Troja, where the river rose some 10 meters over normal levels and trapped the animals in their cages. More than 130 animals, including an elephant, some hippos, a bear and a lion, died in the tragedy. In the aftermath of the flood, the city was temporarily riveted by the flight to safety of a sea lion named “Gaston.” In the chaos, Gaston had somehow found his way to the Vltava and was reported to be swimming northward. It felt like a gut punch for the whole city to learn later that Gaston had perished from exhaustion near Dresden.

The August 2002 flood leveled whole districts of the city and caused some $3 billion in damages (the real bill was probably much higher), yet the legacy of that disaster – seen from two decades’ distance – is largely positive. The riverside districts damaged in the flood, places like Smíchov, Karlín and the eastern end of Holešovice, included some of the city’s poorest and most-neglected neighborhoods, and the floods spurred long-overdue efforts to rebuild and revitalize these areas. Today, they’ve been transformed into some of Prague’s most desirable places to live and spend time in.

The tragedy revealed serious weaknesses in the city’s flood-protection infrastructure that have since been corrected. The banks of the river now have permanent mounts built into the ground so that the temporary flood walls can be installed in a matter of minutes if needed. The metro stations have been hardened against rising water – though I’m not sure I’d trust the system to withstand another big flood (let alone a nuclear war). The zoo has since moved the cages of large mammals to higher ground. Gaston now has his own statue.

In a bigger sense, the flood reminded Prague that it actually does straddle a river. The city of composer Bedřich Smetana’s haunting “Moldau” symphony had somehow over the decades turned its back on the waterway. Planners during the communist period had built their city away from the Vltava, and in the years before 2002, much of the waterfront lay fallow or given over to light industry.

These days, spurred on by the enormous popularity of the Náplavka embankment, south of the National Theater, the city now views the river as a natural asset. Prague’s relationship to the Vltava feels more organic and positive than it did before 2002. I’m not sure this would have happened – or happened so quickly – if it hadn’t been for that massive flood.

This brings us to the COVID-19 pandemic, which while very different from the flood, also shut down the city, cost it billions of dollars in damages and revealed serious cracks in the infrastructure. The biggest crack might be the confirmation of Prague’s near-total dependency on mass (and crass) tourism for its economic survival.

I’m not sure yet what changes might be in the offing or how this latest disaster might shape the city in years to come. I’m heartened, though, by the fact that Prague has already demonstrated an ability to adapt to adversity and come back stronger.