“The Łódź ghetto was like its own country. It was the ‘first Jewish state’ if you will. It had its own post office, seven hospitals, seven pharmacies, a cultural center, a theater, and a symphony. It even had its own president: Chaim Rumkowski.”

Those are the words of Hubert Rogoziński, a local historian and volunteer at Łódź’s Jewish Community Center. At one point, Rogoziński made his living principally as a taxi driver. Now, he’s a highly sought-after tourist guide, catering to an ever-growing number of visitors curious to learn the gripping history of this industrial city of 800,000 people, 120 kms (72 miles) southwest of Warsaw.

Few people outside of Poland will know much about the country’s second-biggest city. Łódź grew wealthy in the late-19th and early-20th centuries as a booming textiles center. More recently, though, it has fallen on tough times, as jobs moved to lower-wage countries abroad and Poland’s cash-strapped government could do little to arrest the decline.

It’s also burdened by a name that’s vexing to non-Polish speakers. The "Ł" is soft like a whisper and the "o" is more of a long u; the city is pronounced “Woodge.”

But these days Łódź is on the rebound. Part credit goes to Poland’s booming economy, which has seen the jobless rate fall from 20 percent a decade ago to around 8 percent. But part also goes to an enlightened city government that -- to an extent still somewhat unusual in Poland -- has sought to highlight Łódź’s Jewish heritage, including the grim years under Nazi-German occupation, as a way of drawing attention to the city.

A few years ago, the Łódź City Hall and the Jewish Community Center joined forces to build a heritage trail through the area of the former Jewish ghetto, including the city’s vast Jewish cemetery and the train station from where thousands of ghetto residents were deported to the Nazi-run extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. With the help of a detailed map and brochure available at the tourist office, visitors can walk the former ghetto at their own pace and see for themselves what happened here.

The effort is paying off. While there are no precise figures on visitors to the former ghetto, the numbers clearly are rising.

Symcha Keller, the leader of Łódź’s small surviving Jewish community of around 1,000 people at the time of our interview, says that for decades after World War II the history of the Łódź ghetto was forgotten. “The communists were not interested in the history of the ghetto, and few people were coming here.” Now, he says, “it’s opened up a whole new history for us.”

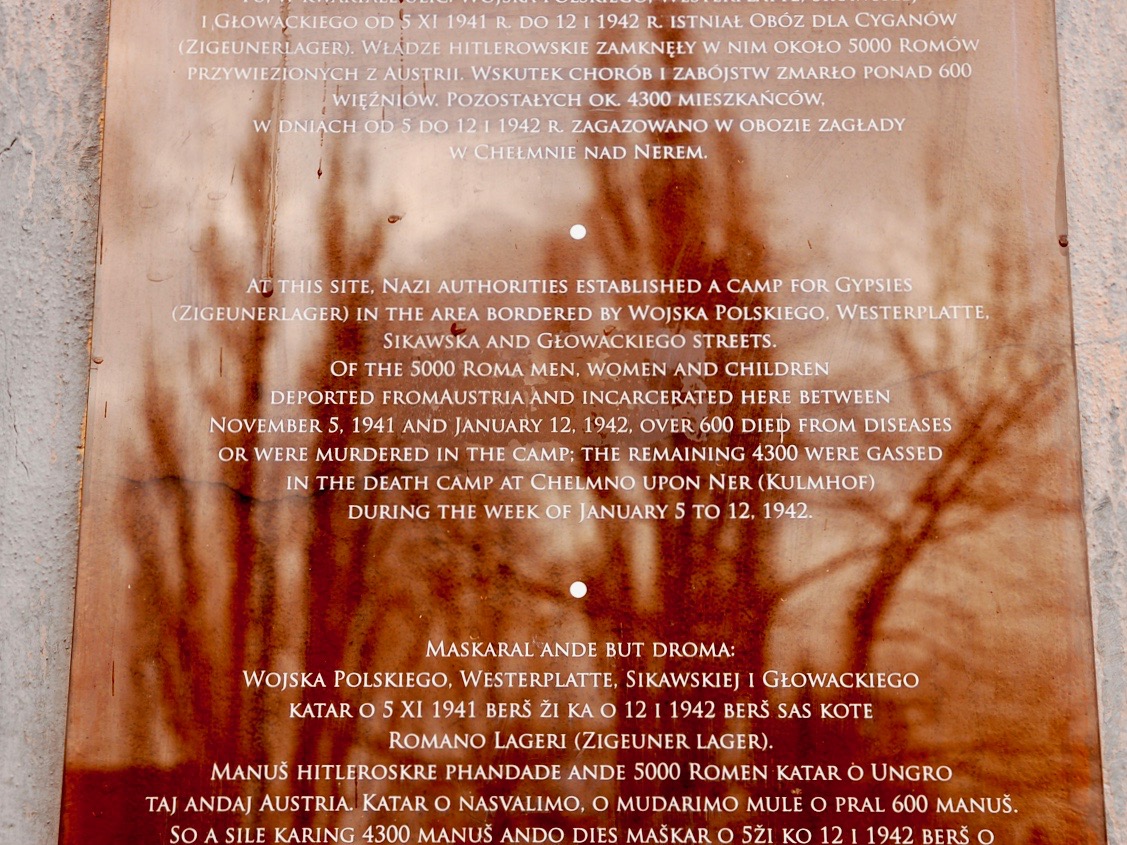

The story of the Łódź ghetto is one of the most remarkable of the war. It was both the first large ghetto to be set up by the Nazis, in 1940, and the last to be liquidated, in 1944. At its height, the ghetto held around 200,000 people -- mostly local Jews, but also sizable groups from Prague, Vienna, Berlin, Hamburg, and Luxembourg, as well as 5,000 Roma from Austria’s Burgenland province.

“The Łódź ghetto was not a typical ghetto. It was unique in Poland,” says Rogoziński. For one thing, he says, the ghetto was not primarily a holding center, as in Warsaw, but a forced labor camp, harnessed to the German war effort. Rogoziński says that after the Warsaw ghetto was liquidated in 1943, “Łódź was practically the only place in Poland where you could find a community of living Jews.”

For four long years, the ghetto survived under the highly controversial leadership of Jewish elder Chaim Mordechai Rumkowski. It was Rumkowski who led a policy of deliberately collaborating with the Nazis as a way of prolonging the lives of ghetto inhabitants. When in 1942 the Nazis demanded more victims to clear space, Rumkowski infamously pleaded with the ghetto's mothers to give up their children. The mothers refused, but in the end some 7,000 children were rounded up and shipped to the German-run Chełmno (Kulmhof) extermination camp.

“I cannot speak about Rumkowski, whether he was good or bad,” says Rogoziński. He says about half the Jews who lived in Łódź still despise Rumkowski; the other half credit him with saving the lives of the 7,000 to 14,000 Jews here who survived the war. “The ethics and norms of the ghetto were different from our time,” he says.

The Nazis liquidated the Łódź ghetto in August 1944 in a desperate move, as Poles in Warsaw began to rise up against the Germans and the Soviet Red Army began closing in on German positions from the East. The Nazis sent 73,000 Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau in a 20-day period from August 9 to August 29. Rumkowski himself was one of the last to go. He died at Birkenau on August 28.

After the war, very few of the survivors decided to return to Łódź, and the tragic story of the ghetto was eventually buried under a mountain of communist propaganda.

Jarosław Nowak, an adviser to former Łódź mayor Jerzy Kropiwnicki and initially one of the main proponents of efforts to highlight the ghetto, says under the communists, particularly from 1968 until 1989, “Jewish issues were completely taboo in Poland.” After 1989, he says, there were simply too many other problems to solve. “People were not focused on the Holocaust.”

Ironically, perhaps, it took the election of the staunch right-wing Kropiwnicki in 2002 to initiate the change. Nowak says Kropiwnicki, at first, knew little about local Jewish history. “It was only after he met with families of the survivors and saw how disappointed they were that the history had been forgotten that he resolved to do something about it.”

Jewish leaders initially were skeptical. Now Łódź is often held up as an example for other Polish cities, including Warsaw and Kraków, which for years had been criticized for being too slow to make the Holocaust sites more accessible to visitors.

Warsaw, for example, was home to Poland’s largest pre-war population of Jews and its largest wartime ghetto of nearly 400,000 people. In 1943, the Jews heroically rose up against the Nazis and then paid the ultimate price after the uprising was put down and the survivors shipped off to the Nazi extermination camp at Treblinka. Yet, aside from a couple of statues, for years visitors searched in vain for signs of the ghetto’s existence.

That situation was at least partially remedied in 2014, with the opening of the exhaustive, high-tech Museum of the History of Polish Jews (POLIN).

The situation was marginally better in Kraków, where interest in the city’s former Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, rose dramatically in the 1990s thanks in part to director Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning movie “Schindler’s List” in 1994. Kazimierz now hosts a popular festival of Jewish culture and the Jewish quarter has become an integral part of the city’s tourist trail.

Kraków’s own wartime ghetto at Podgórze, where tens of thousands of Jews were herded up during the war, is now undergoing something of hipster-fueled Renaissance because of its still-affordable housing stock. Oskar Schindler’s old enamel factory – the site of the “hero” of the Spielberg film for his role in saving the lives of around 1,000 Jewish workers – has been reopened as a museum dedicated to Kraków’s history during World War II.

Back in Łódź, the best way to approach the ghetto is first to pick up the brochure “Jewish Landmarks in Łódź” from the tourist office. The walking tour begins at the central Bałucki market and runs along the southern edge of the ghetto to the Jewish Cemetery and the Radegast train station. There are short explanations on each of two dozen suggested stopping points.

There are only a few real highlights along the way. The district remains one of the poorest in a relatively poor city, and most of the points of interest – the former barracks of Jews from Prague or Vienna, for example, or sites of hospitals or schools -- amount to little more than abandoned buildings or what look to be bombed-out shells.

If anything, though, the enduring poverty only serves to heighten the impact. Very little has been cleaned up or sanitized; it’s a piece of living history. Something of the spirit of the former ghetto still hangs in the air.

Łódź’s massive Jewish cemetery – dating from the end of the 19th century -- lies toward the end of the trail. The cemetery covers 40 hectares and holds more than 200,000 graves. Around 45,000 ghetto victims are buried in mass graves. The most moving sections, perhaps, are the countless rows of untended and overgrown graves from the 19th and early-20th centuries. It takes a moment for the realization to sink in: the graves are untended because no one from these families survived the war.

Beyond the cemetery, another 20 minutes by foot, is the Radegast train station, from where the deportations left. Visitors today see the station much as it appeared to ghetto residents as they were marched here in the summer of 1944 for the final journey to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Three Deutsche Reichsbahn cattle cars are sitting on the tracks, their doors still left open.

(A couple of months after I posted this story, Poland introduced a new law on the Holocaust that could criminalize implying that Poles themselves had anything to do with the genocide. I wrote down my thoughts on the law and a wider discussion on the Nazi Holocaust in Poland on this link here.)

A special thanks for the map given. It helps us to know the accurate information about the places in which we are interested in. So, thank you for sharing. Have a good day.