I first became acquainted with the Baths of Hercules not from visiting but through the writing of the late, great English travel author Patrick Leigh Fermor and his book, “Between the Woods and the Water.”

The book is the second (and best) part of a trilogy that documents a trip the author took as a young man in 1933 and ‘34, traveling on foot (and horseback) all the way from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople. The “Between the Woods and the Water” segment starts in the former Czechoslovakia and traces Fermor’s journey south and east through Hungary and Romania. The book ends near the Danube, where the river flows between Romania and Serbia.

Fermor’s book is amazing in several respects. First is the fact the author only finished the book in the 1980s, more than 50 years after he took the trip. He constructed the narrative and his copious description wholly from notes and memory. Second is the quality of the description itself: dense, poetic and hypnotic. He stretches the reader’s vocabulary in ways most modern writers wouldn’t dare. The result is a read that’s at times difficult but immensely satisfying.

Here's his description of the Baths of Hercules in 1933:

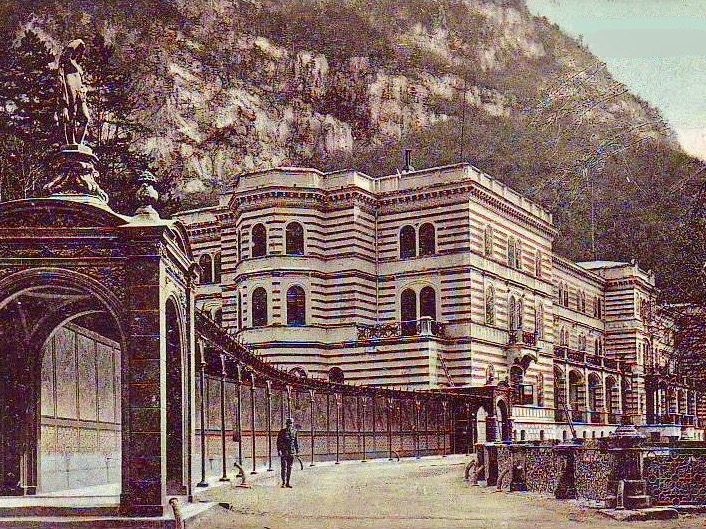

“Suddenly, and without warning, an ornate and incongruous watering place called the Baths of Hercules rose from the depths of the wild valley. The fin-de-siècle stucco might have come straight out of an icing gun; there were terracotta balustrades, egg-shaped cupolas and glimpses through glass double-doors of hydrangeas banked up on ornate staircases … an echo of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at its farthest edge.”

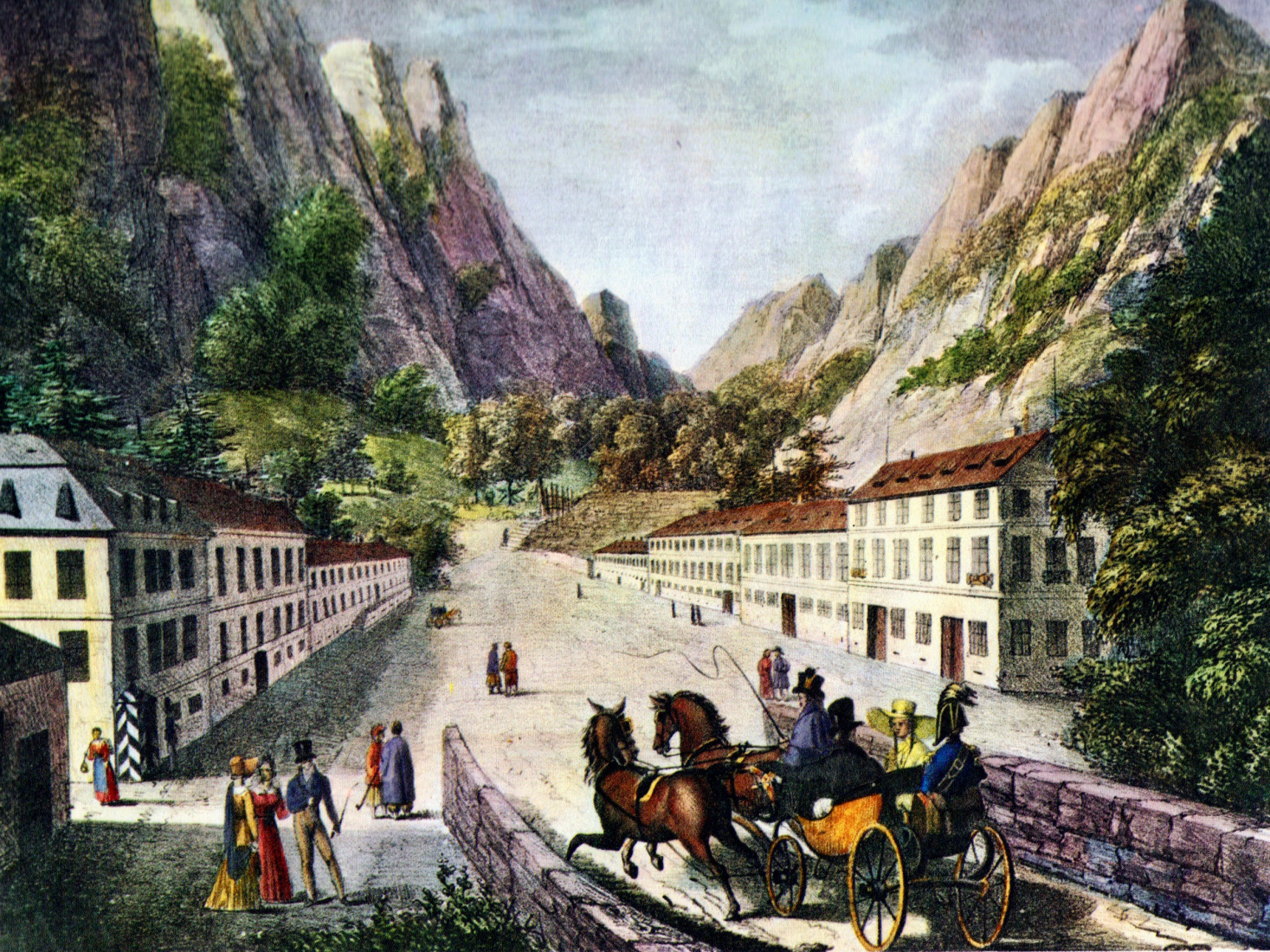

The Baths of Hercules must have been an amazing place. The hot springs trace their roots to the Romans in the second century AD, after they’d finally succeeded in bridging the Danube (in 105 AD) at the modern-day port city of Drobeta-Turnu Severin. From the river, Roman armies advanced north to conquer the indigenous Dacian tribes and rule over this part of modern-day Romania for around 170 years.

It was the Romans who first gave the baths the name of "Hercules" (Ad aquas Herculi sacras). In the intervening centuries, the baths were lost to time and only rediscovered by the Austrians in the early 1700s. The first excavations at the site uncovered six Roman statues of Hercules, and a bronze replica of one of those stands at the center of the spa even now.

The baths flourished under Austrian-Habsburg rule in the 19th century. Emperor Franz Joseph visited in 1852 and proclaimed the baths to be the most beautiful on the European continent. His wife, the Empress Elisabeth (Sisi), was a big fan and preferred this resort to the many other spas within the empire at the time.

By the time Fermor rolled into town in the 1930s, the baths were still going strong. Following the defeat of Austria-Hungary in World War I, the region had passed from Hungarian to Romanian control, though Fermor describes a still-surviving ethnic tapestry of well-to-do Hungarians, Romanians, Germans and Slavs, collectively enjoying the decadence of the casinos, the baths, the drinks and the dance.

During the Ceaușescu years, after World War II, the baths survived but the decadence did not. Communists tended to be ideologically uncomfortable with the notion of wealthy people “taking the waters.” The Baths of Hercules were opened up to mass tourism and given a kind of working-class, medicinal cast. Big hotels and recreational cooperatives were built up around the central spa, but the historic core remained intact.

It was only after 1989 and the fall of Communism that the whole thing began to unravel.

I first visited the Baths of Hercules in 2012 on assignment for Lonely Planet. Armed with Fermor’s book, I was expecting to find those illustrious terracotta balustrades and egg-shaped cupolas, but instead what I saw were broken windows, chipped statues, rusting pipes, and neo-baroque buildings sliding into the Cerna River that runs through the resort. My strongest memory from that trip is of flies and stench. I was witnessing the decomposition first-hand.

The story of what happened to the Baths of Hercules is too long and complicated to tell here, and I’m not sure I fully understand it myself. From what I gather reading the local news reports, it involves the usual suspects of corrupt local officials willing to make deals and take payoffs from unscrupulous businessmen whose only interest, it appears, is to loot and extort.

The result is a protracted courtroom battle over the rights to the spa -- and the obvious irony to anyone visiting is that under Romania’s twisted system of gangster capitalism, it somehow makes more sense to let the buildings rot than to restore them to their former splendor.

On this most recent trip in 2018, I found more hopeful signs. The air of despair had dissipated and some of the older buildings had received a fresh coat of paint. Here and there, I saw scaffolding (but no workers). It looks as if, slowly, the process of renovation has begun.

(After I posted this story, a Romanian friend sent me a link to another story by a Romanian architectural student, Oana Chirila, whose own writing and photography have already spurred some tentative efforts toward renovating the baths. Find her story here.)

Work has apparently not yet started on restoring the spa’s most glorious building, the old Neptune Baths (also called the Austrian Empire Baths), which stand across the river from the main road. The historic iron bridge that links the baths to the road remains closed as it’s too dangerous to cross.

As I travel around Romania on this trip, the country finds itself once again in the throes of political upheaval. Mass anti-government protests in Bucharest earlier this month ended in tear gas and anger, and it’s not clear what will happen next.

Romanians are mad at their rulers for many reasons, including the fact their country has not made more significant economic progress since 1989 and that people continue to leave the country in droves for better opportunities abroad in Italy, Spain, and the UK. But if there’s one issue that unites the protesters above all others it would be the continued widespread corruption at all levels of business and government.

It’s possible this story of the Baths of Hercules doesn’t quite fit this corruption narrative perfectly. As I wrote above, I don’t know all the details behind why the baths have been allowed to fall into ruin. It would be hard, though, to find a more potent symbol for what ails this country. At the risk of ending on a bad pun, the task of rebuilding the baths is befitting of a guy, well, like Hercules.

This is a great & sad story very beautifully written. Thank you Mark! I shared it already.

Thank you Lucian, and for sharing!

What a place! Good to hear there’s some hope for things moving forward and hopefully that won’t be stalled by an unfortunate political development.. Let’s see.

Btw. beautifully written! And you wrote this quickly?! Wow.

Thank you Veronika! The place has such amazing potential.

After I posted this article, I heard from many Romanian friends on FB and Instagram. Although the story is quite critical, most people reacted positively to it. The only way to bring about change is to shed light on the issues (and not mince words).

One friend sent me this link (below) to another blogger and photographer whose story has apparently already catalyzed efforts to renovate the baths. Keep up the good work!

https://www.boredpanda.com/the-unbelievable-story-about-how-an-article-became-a-project-the-story-of-herculaneproject/

Here is the link to the story that Oana Chirila, a 23-year-old architectural student from Timisoara, wrote that has prompted efforts to restore the Hercules Baths: https://www.boredpanda.com/stunning-interiors-from-abandoned-thermal-baths-in-herculane-romania/?utm_source=markbakerprague&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=organic

Great story, Mark, and a sad one! I hope the baths are restored one of these days.

Chalk number two up to Colin! Happy you liked the story.

This article (in Hungarian) provides a good account of the decline of Hercules Spa (yes?). Some excellent pictures. https://foter.ro/cikk/20181026_sisi_kedvelt_udulohelye_ma_mar_kisertetvaros/

Hi Mark, I was reading Paddy Fermor’s wonderful book “Between the Woods and the Water” and when he started to describe the Hercules Baths, I googled them and came across your marvelous article and photos, showing their present state.

Thanks very much for such an interesting article

Thank you, Paula. I haven’t been back to the baths since I wrote the story, but I have a feeling that things are getting better there. I’m curious how it looks now. Mark