Our rickety team bus ground to a halt at the Austrian border control post north of Vienna. By “our” I mean the twenty-five or so players and supporters of the Vienna Celtic Rugby Football Club. This side of the border, the Austrian, was the upper Marchfeld, a land of potatoes and sugar beets. Ahead, across a barbed-wire barrier, we could already see the hills of southern Moravia in Czechoslovakia.

It was March 1978 and a dreary rain was falling. The Austrian guards waved us through. A Czechoslovak policeman raised a red- and white-striped frontier boom. Welcome to the border station of Mikulov, ČSSR. Ahead was the regional capital of Brno and then on to our overnight lodging and rugby match the next day in the city of Gottwaldov (now Zlín, see map below).

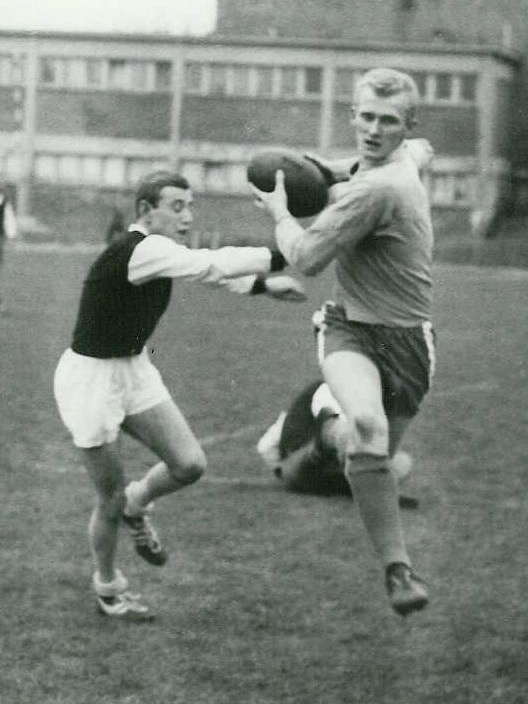

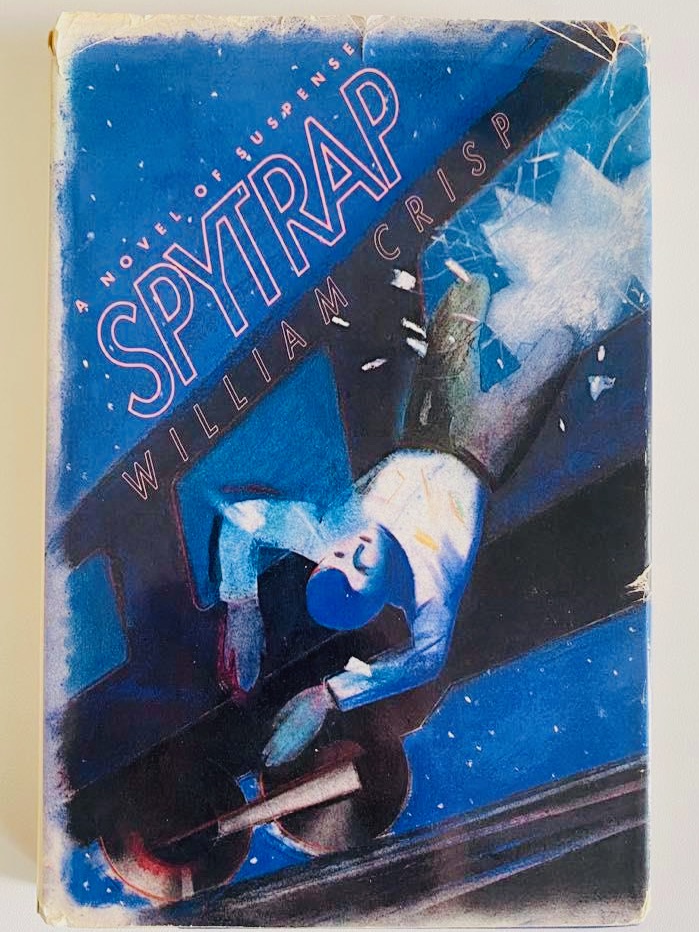

We were there solely to play rugby, and certainly not to carry out any type of undercover work, and this account lacks the overt drama of, say, a John le Carré spy thriller like “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy,” in which MI6 agent “Jim Prideaux” crosses near this same border at Mikulov and is quickly ambushed by the Czechoslovak security police, the StB.

And maybe that’s the point of this story. We didn’t fully realize it on that rainy day, and only came to learn later on this first of many future trips, that in most outward appearances, there seemed little drama attached to Czechoslovakia’s version of Eastern bloc socialism. This was certainly true in comparison to, say, the more intrusive regime of Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu or the later, violent break-up of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. The defining characteristic, instead, appeared to be something closer to petty harassment, a feature that was presumably already well known to Czechoslovakia’s own citizens, and indeed to people across the former Eastern bloc.

Once on the Czechoslovak side, with nothing else to do, we sat in our ancient bus, piloted on this trip by our Austrian driver, Johann. The border police, after thumbing through our voluminous visa papers and passports, disappeared into some sort of official-looking building. After some more prolonged waiting, everybody seemed to be getting restless. Finally, one of the olive-green-gray uniformed border police approached our bus.

“Some of your people have a big problem,” he said.

John Skinner, our team captain and my friend and colleague at Business International, stepped in to mediate. Speaking in his near-fluent Austrian-German, filtered through a native Scots accent, John asked the border guard what was causing the hold-up: “Naja, was ist los?”

The guard, in his own formal German, replied: “In their original passport photos, the American players in your group are all clean-shaven. This is not how they appear in their visa photos, where they all have beards.”

John, always supremely confident, replied: “I’m certain this will pose no problem.”

“Wrong,” the guard said. “Unless they shave off their beards now, they -- and you -- have three options: The 'Yankee' boys can turn around and walk back to Austria. Or your bus can turn around and drive back to Austria. Or the Americans can shave off their beards. Make up your mind, Herr Manschaftskapitän.”

John patiently explained the situation to the American players. Somebody located a cheap, dull Bic razor, the plastic kind, and they all disappeared into the cold-water Mikulov bathroom. Howls of outrage erupted. With their sullen, hungry faces, suddenly scraped raw, our American players returned to the bus and we continued onward to Gottwaldov. The rain kept falling.

We didn’t know what to expect from Gottwaldov and its funny, non-Czech-sounding name (at the time, the city had been re-named for Czechoslovakia’s early Communist Party leader, Klement Gottwald. A little like "Leningrad" in this respect, but on a more modest scale). As we approached the outskirts of the city, through the bus’s fogged-up windows, we spotted numerous neat-looking, red-brick, two-family homes, with their well-tended vegetable gardens. A little further on, we encountered rows of duller-looking, pre-stressed concrete apartment blocks, ring upon ring. Much to our surprise, though, the sports complex for Gottwaldov’s rugby club was far from looking run-down. The well-maintained main building was equipped with changing rooms, showers, and a clean-looking social hall, all facing a regulation -- if a bit muddy-looking -- rugby pitch.

On arrival, the local rugby players and club officials invited us inside and offered up big pitchers of Czechoslovakia’s famed beer (pivo). The lingua franca on that trip was German, with a bit of English mixed in. Whatever language barriers that might have existed, though, quickly evaporated. It felt like a pure moment of international Freundschaft.

We were booked that night in the tall, nearby “Interhotel Moskva,” and took a supper of rather tasteless noodle soup and some rubbery schnitzel. No matter. It was all washed down with more of that outstanding local brew.

The rugby match the next morning went well – that is, for the Gottwaldov Rugby Football Club. We Celtic players fought a good game, and made plenty of saving tackles in the mud, but we couldn’t quite pull off a win against the Czech side. After hot showers (no austerity here), more hearty fellowship followed.

Throughout our rounds of drinking and the match itself, we didn’t engage much in political discussions. Our exchanges on that particular trip only started to veer into more-complicated territory when I noticed a large mural that depicted workers tanning hides in a shoe factory. With a couple of discreet questions, I learned that Gottwaldov’s main industry was shoe-making -- indeed, the local shoe factory was probably the rugby club’s affluent sponsor. Somebody, possibly one of the Czech players, then mentioned the name, “Baťa.”

One of our players, probably John, chimed in under his breath: “[Tomáš] Baťa was the former owner of the factory. [His company] built those pretty brick homes with the gardens for his workers.”

Indeed, I didn’t realize it at the time, but Baťa’s legacy still ran very deep in Gottwaldov. After company founder Tomáš Baťa Sr died here tragically in a plane crash in 1932, control of the local Baťa shoe company passed to his half-brother, Jan Antonín Baťa, and son, Tomáš J. Baťa [Jr]. They then succeeded in building the company into one of the world’s largest shoe-making empires. A big part of the Baťa company’s success was its policy of treating its workers well, including – as it had done here -- providing them access to decent housing and sports facilities. During the Nazi occupation in World War II, the company was seized by the Germans and the owners forced to emigrate. After the war, it was nationalized by Czechoslovakia’s communist government.

At the time of our match, I didn’t have much background here, and John’s remark took me by surprise. “So,” I asked, “Baťa was a progressive, you know, enlightened owner?” The ever-direct John didn’t hold back: “The communists … denounced him as a blood-sucking capitalist.”

Just before we got back on the bus, one of the Czechs mentioned, very quietly, that the local Communist Party functionaries had begun moving their families into those brick bungalows just as soon as Baťa came under state control.

That groundbreaking trip to Gottwaldov was just the first of numerous overnight trips up and down the Moravian road that included return matches against Gottwaldov, as well as matches in Olomouc, in the sugar-beet-factory town of Vyškov, and in the Moravian capital, Brno, itself. The Brno sides, in particular, always seemed to have some heavyweight sponsors. These included Ingstav, backed by a construction company that reportedly did a lot of overseas work in Libya. The real big guys were Zbrojovka Brno, who played on an iron-hard pitch. Nobody said much at the time, but we all got the impression that Zbrojovka’s backers did things like make tanks for the Soviets.

On these trips, we always tried to be on our best behavior, though inevitably we’d run into misunderstandings and cultural clashes. A couple of trips stand out in particular. On one Saturday in autumn, we found ourselves booked into a student dorm in Olomouc prior to the next day’s match. It was harvest season and we shared our wing of the dormitory with a group of female students down the hall. Naturally, there was a lot of conversation back and forth. Eventually, somebody pieced it together that the women were part of a brigade who had “volunteered” to help pick the all-essential hops for Czechoslovakia’s beer industry.

Just then one of the women, clad only in flip-flops and wrapped in a bath towel, came strolling down the hall from the showers. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to figure out what happened next. Johann, our driver, couldn’t resist the opportunity to make some (clearly unwelcome) chit-chat. The woman looked him straight in the eye and launched into a full-throated rebuff, in both Czech and German. “You don’t want to know what she called him,” someone said, translating from the German. A chastened Johann slunk away.

On another trip, we were returning to Vienna and stopped for a meal at a local restaurant. My Celtic teammate, Andrew MacDonald, was a Scot from Inverness, an accountant who joined our side whenever he was on company business in Vienna. He was a dark-haired, 200-pound (90 kg), front-row prop, dead serious and intimidating in matches, but a rogue once the final whistle blew. And there he was, suddenly, wearing his kilt and standing on a chair in the middle of a very surprised group of local diners. “If you like the Russian soldiers, kiss my ass,” he bellowed. “If you like the Russian soldiers, if you like the Russian soldiers, if you like the Russian soldiers, kiss my ass!”

After the Russian-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the crackdown on political reforms and freedoms that followed, it would have been very hard that day to find anyone in the restaurant, Czech or otherwise, who was overly fond of Russian soldiers. In that respect, at least, we were all on the same side. Andrew probably hadn’t realized that (things weren't always how they seemed) and took the opportunity, unfortunately, to blow off some steam. It was the Cold War, after all.

That incident, thankfully, ended amicably enough (and didn't erupt into an international incident) after a Czechoslovak cop in plainclothes, who’d been sitting alone at a corner table, stepped in. He walked over to John and told him bluntly: “If your friend doesn’t want to spend the next six months in one of our jails, tell him to get down off the chair and shut up.” John turned to Andrew, one Scot to another, and told him simply, “Get down off the chair and be quiet.” And that was that.

Over the next few years, the Czech clubs visited us on several occasions for matches in Austria and all went smoothly. We never heard of any defections or of any players staying behind and not getting back on the bus for home. We suspected there must have been some kind of unwritten agreement between the regime and the clubs, something along the lines of “don’t rock the boat and we’ll let you lead a normal life.”

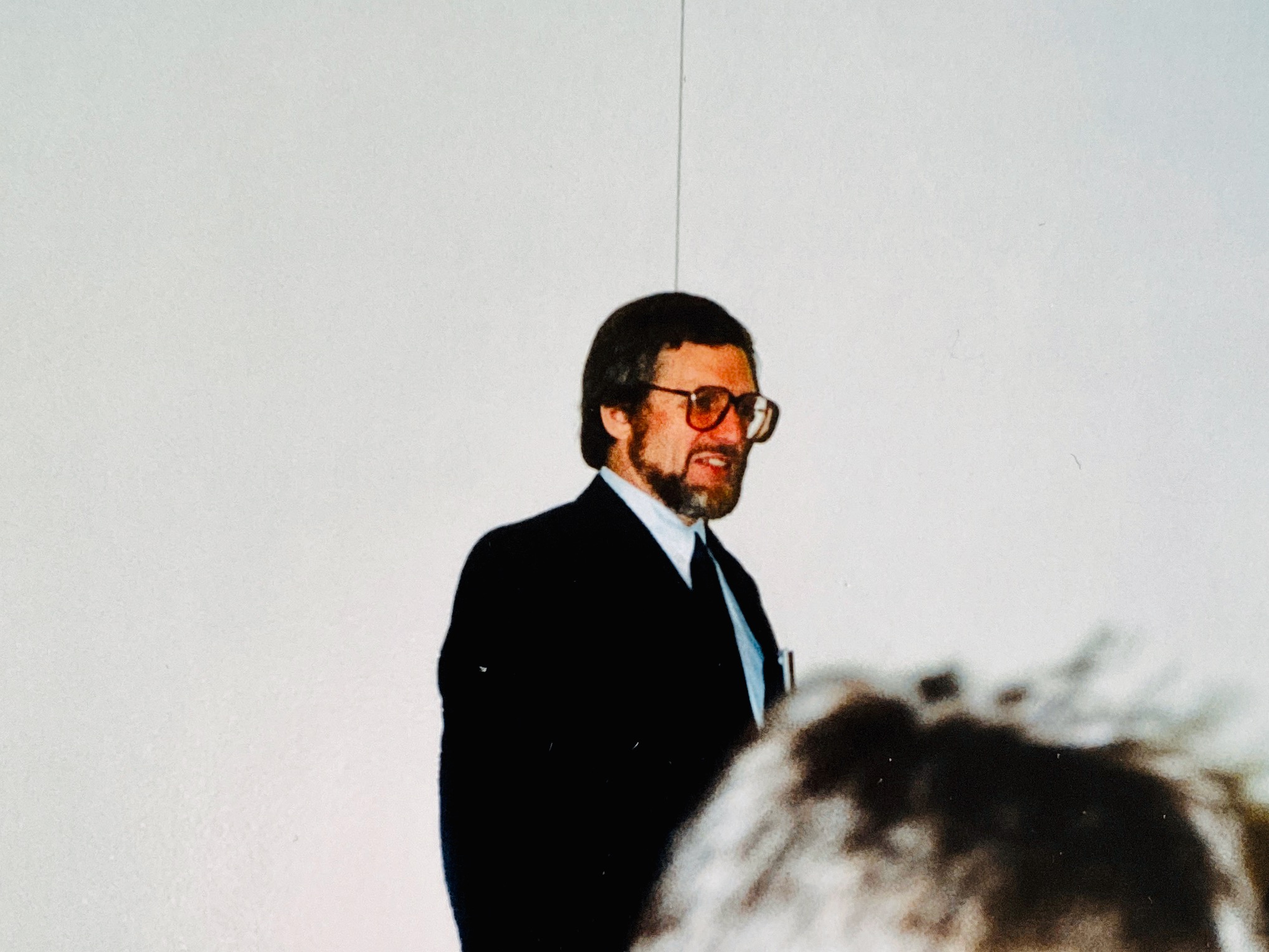

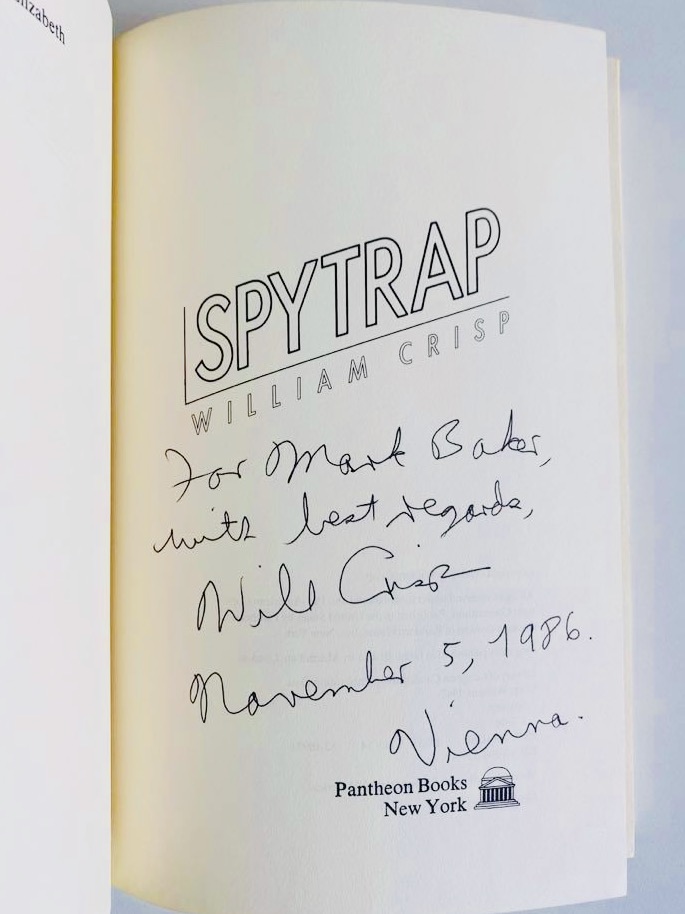

I’m not sure of that, but I definitely do recall gaining a grudging respect for what had been, at the time, a very capable opponent and bonding, across the ideological divide, over a shared devotion to the game of rugby. -- William Crisp

(William Crisp served as Lieutenant, First Cavalry Division (Airmobile), in Vietnam in 1966-67. He worked as a U.S. Foreign Service Officer in Zagreb, Yugoslavia (Croatia), from 1968-70. He later became a country analyst and manager for Business International’s Vienna office from 1974-1999. He was an associate professor at the Virginia Military Institute and coached VMI’s Rugby Club from 2000-2007. He lives in Staunton, Virginia.)

Mark, I really enjoyed reading this blog which Christa Skinner forwarded to me. I was a founder member of Vienna Celtic Rugby Club along with my flat mate Phil Walsh. We met John and Will whilst doing a student year abroad in 1977-78. The text brought back so many great memories and fun times with the team on and off the pitch. We enjoyed the club’s 40th anniversary celebration a few years ago when a number of the original players were able to make it back toVienna. I am still in touch with a number of these ex-players.

Coincidentally I have also met Danny Thorniley a few times at conferences where he was a speaker.

I share your interest in Central and Eastern Europe and will look out for your book.

Hi Rob, thank you for leaving a comment and I am really happy you liked Will’s story. Lots of memories! Mark

Here’s a note to Will from Letitia — Your piece on playing rugby brought back oddly fond memories of life in that somewhat surreal part of the world back when Europe was still divided. You probably don’t recall this, but you interviewed me for my job at BI at Dulles Airport on a Sunday in April 1987. On the day before, a Saturday, you had been playing rugby in Czechoslovakia. I remember you telling me your rugby plans over the phone when we were scheduling the interview. You made a wry joke to me over the international call (that sounded like you were calling from across the Atlantic Ocean), and that was that you would see me on Sunday at Dulles as long as the Czechoslovaks did not arrest you and your rugby team members on Saturday. I remember thinking how surreal it must have been for you to be in the East Bloc the day before as you, Anita and I sat in some Dulles cafe lounge. A couple of years later, Europe managed to break away from that divide, but now I fear that the continent is heading back into another divide what with what is going on in Ukraine. I hope that you and your family are well. Whenever I meet up with Jim, I always ask if he has heard from you. Best wishes and fond memories, Letitia

What a pleasure to read this! I spent quite a few years working for the author in Vienna, and of course his love for rugby couldn’t be missed. It was the big topic on many an otherwise dreary Monday morning in the office, especially because Will and team captain John Skinner were colleagues at our company. In fact they were the two senior guys, and their close friendship gave a certain direction to everything we did in those days. They used to go out to lunch together every day, without fail, and drink a couple of half-liters of beer while arguing ferociously about a book they were both reading, or some arcane aspect of European history, or of course rugby. I’ll never forget coming into the office one morning and seeing John (I think, or could it have been Will?) wearing a Count of Monte Cristo mask – his nose having been literally crushed in a game the day before. So rugby and those lunches were the twin drum beats underlying our working life. As one of the so-called “junior editors,” however, I had to draw a line somewhere. I was stubbornly determined NOT to play rugby. Getting my limbs broken in the mud was not going to be part of my life, no matter how much I liked and admired Will and John. Funny thing is, I regret that now. A broken limb would have healed, after all.

Thank you, Jim, for leaving a comment and reminding me about those lunches 🙂

Dear Mark:

How great it is to read this story. I joined Vienna Celtic RFC in 1984, and still am an active member, although my activities are now limited to refereeing and once a few months an old boys tournament. Will’s story brings many many memories, and makes me feel proud, especially seeing what has become of our little club, the first Rugby Union side in Austria, est. 1978. By now we run a womens team, several kids teams, and have a thriving Vienna Celtic community all over the world. One of the highlights was over 50 former and active Celts from all over the world visiting the Rugby World Cup 2015 in Wales and England.

Unfortunately John Skinner died of Corona in the autumn of 2020, which is a very sad occasion. Nevertheless, all of you who have been at Vienna Celtic RFC, the club is doing great, has it’s own rugby ground in Vienna now, and will last forever!

Thanks Mark for these memories! Ogi Ogi Ogi!

Andreas

Nice and familiar fond memories. However we lived it from the other side of the table as being under Soviet occupation that seemed never ending even at the late 80s.

Vienna started to visit Hungary in 1979, first BEAC and predecessor Botond RC – the sole rugby club that remained after an early start of organized rugby in 1969 by an Italian Embassy guy called Carlo Passalaqua. Some 6 or so teams were created, but after his leave to Germany in 1972, only two teams remained playing randomly against each other till 1979 when a decision was created to revive somehow the real rugby life here, in this corner behind the iron curtain.

So it was BEAC (a University Club of Budapest) who were contacted by Vienna Celtic. A letter came form Will Crisp to Budapest, mysteriously posted from Ljubljana, the today Slovenia to initiate the contact in January 1979. It resulted in the first Vienna match in Budapest on 5th May, 1979.

Not much after the second today’s team was established in the countryside in Kecskemét and they soon also played their first match on 19th October, 1980. I mean we, as I joined to the team as a college student there in that early autumn.

And from then on several back and forth visits have come until now. That decade could be featured by the atmosphere written above in the article.

From our side they also had the special charm. Until the fall of iron curtain, we were allowed to cross it only every second year. Due to the sport activity, we could do it every year, in the case of Kecskemét GAMF every autumn, while Vienna regularly came to us every March or April. Just one example of the charm of the Wien trips was that our first tour went to Naschmarkt on Friday afternoon after arrival in Vienna. We bought up all the overripe bananas sold at discounted prices at that late hour- and certainly we eat them all within an hour. One feature of communism was lack of everything, even in Hungary that was called a happy barrack of the communism, I mean we at least had enough to eat, but we could not buy even bananas regularly. The other reason of course was luck of schillings, our currency’s exchange rate was ridiculous those days. Just two pedestrian facts of the many humiliating during communism.

Back to rugby, we also started to meet regularly in Gy?r, that is a town close to the Austrian border. It gave the three teams some convenience regarding the organization of matches. And as of 1982, we organized some kind of national team matches between Austria and Hungary. Here in Hungary we were not allowed to established Union those days for ideological reasons – it happened only after the fall of socialism in 1990, so we created a Hungarian National League Team (not thinking about rugby 13 those days). At the other side of the border they also created teams where several Austrian played as well.

But all these occurrences can be followed in my documentary website, i am building for 10 years and now have more then 5,500 documents or photos there in chronological order, see at http://www.ecbservices.hu/RogbitortenelemHu – Google Translator might help to understand it efficiently.

All in all, the travels of Vienna gave us a lot to create today’s rugby in Hungary including many national teams, both men and women and age grades. And it was nice to read the Zlin memories.

Many thanks to Mark and Will!