I had blissfully traveled around the planet for three decades before even considering the question of whether travel was itself political. During the 1980s, I toured around Communist Czechoslovakia and much of the rest of Central & Eastern Europe when those countries had the most repressive governments in Europe. It never occurred to me then – and I’d still reject the notion today – that my trips were somehow, in some small way, helping to sustain those regimes.

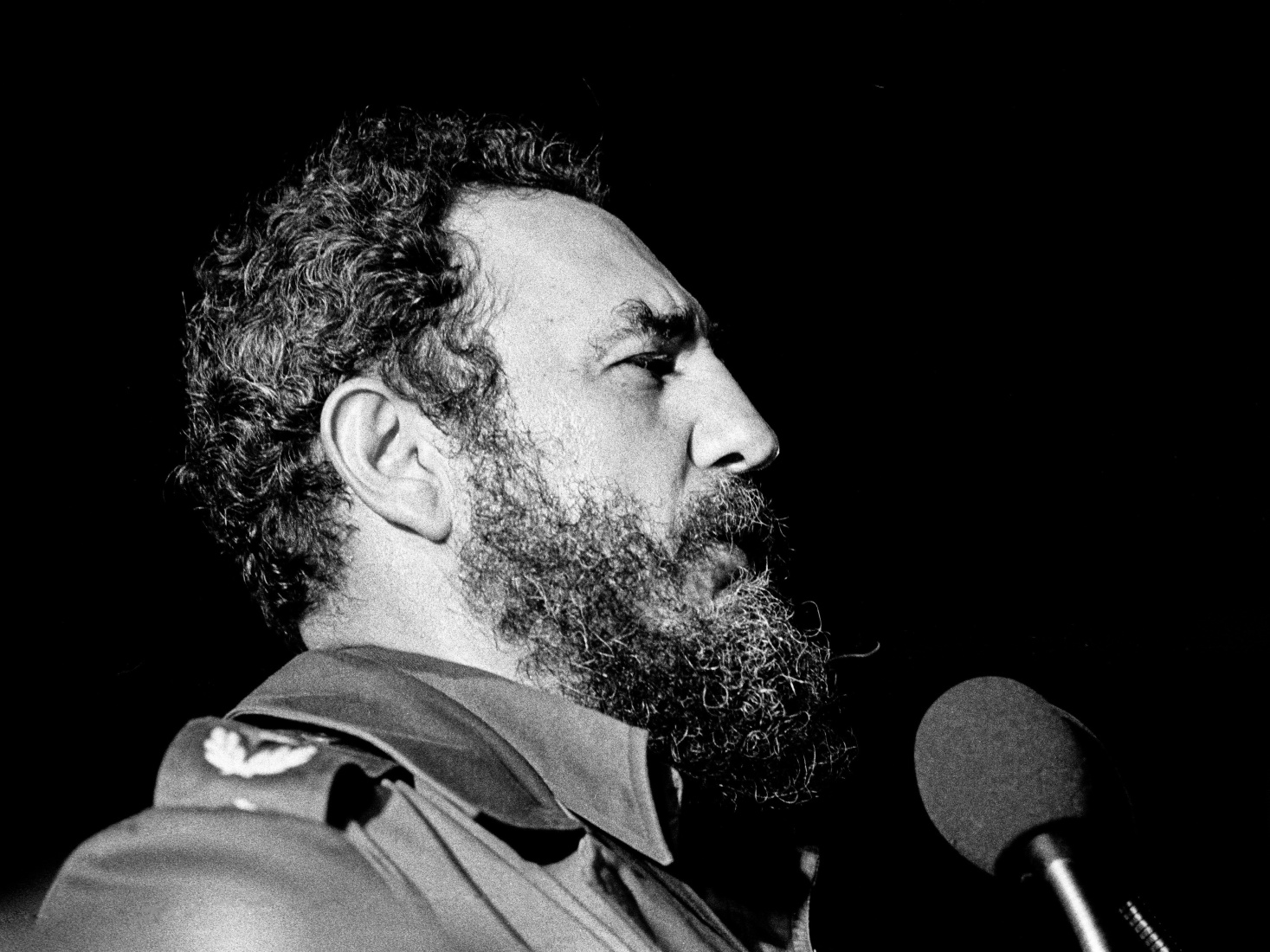

My perspective on all this changed slightly, though, last summer when I met up for lunch in Prague with a Czech friend of mine, Hana. She’s a photographer who’s spent a lot of time in Cuba and has strong opinions on the regime of the late Cuban president, Fidel Castro. She was helping to organize a cultural exchange to bring over some anti-Castro artists and musicians to the Czech Republic and said she wanted to ask me to help translate some promotional materials for the event into English.

Hana spent her childhood in Communist Czechoslovakia and, understandably, has a few choice words for what she considers to be woolly-headed leftists. I live here now, so I’m used to this perspective. Many of my Czech friends feel the same way.

Still, I wasn’t totally prepared for the anger she felt toward certain travel writers and guidebooks that, in her opinion, tread too lightly on the evils of the Castro regime. To paraphrase her argument: those writers are way too infatuated with Castro’s romantic, revolutionary image and colorful anti-Americanism to render an honest assessment of what is, in fact, a brutal dictatorship. Indeed, they make things worse by pushing tourists inadvertently (and inevitably) into Castro-family businesses, which, in turn, only strengthens the regime’s hold over the country.

I know next to nothing about Cuba and wasn’t prepared that day to rebut her arguments. I defended travel writers by saying we do our best to describe places objectively, and besides, it’s not our business to exclude countries because we don’t like the governments (or even blacklist businesses because we don’t like the owners). It’s up to readers to make those decisions.

But it got me thinking. Maybe I’m a little out of touch. Is there an evolving political dimension to travel and, if so, what are the contours?

Hana had one more conversational topic up her sleeve, and that’s when I learned what was probably the real reason for our lunch. She wanted to ask me, as someone in the business, if I thought there was a market for a line of guidebooks or travel publications that would focus specifically on the political aspects of travel, and help travelers make more politically and socially aware choices about where they go and what they do when they get there? The publications wouldn't necessarily dissuade people from visiting places like Cuba, but rather help to educate them on the various ways their travel dollars were abetting the regime (and presumably make better spending choices on the ground).

She thought the idea made perfect sense as a travel guide to Cuba, but the two of us quickly came up with a shortlist of other countries where this information might prove helpful. How about going to Belarus, which never actually made the transition to democracy and is run by a guy often referred to as Europe’s “last dictator:” Alexander Lukashenko. Iran – where the government is highly involved in private business and would profit enormously from increased tourism -- is another obvious candidate for such a title. The list is endless, actually.

We left it with me saying I’d give the idea some more thought, which is to say I promptly forgot all about it. That is, until this political-dimension thing started rearing its ugly head on a guidebook I’d actually recently worked on myself. Suddenly, it all felt very close to home.

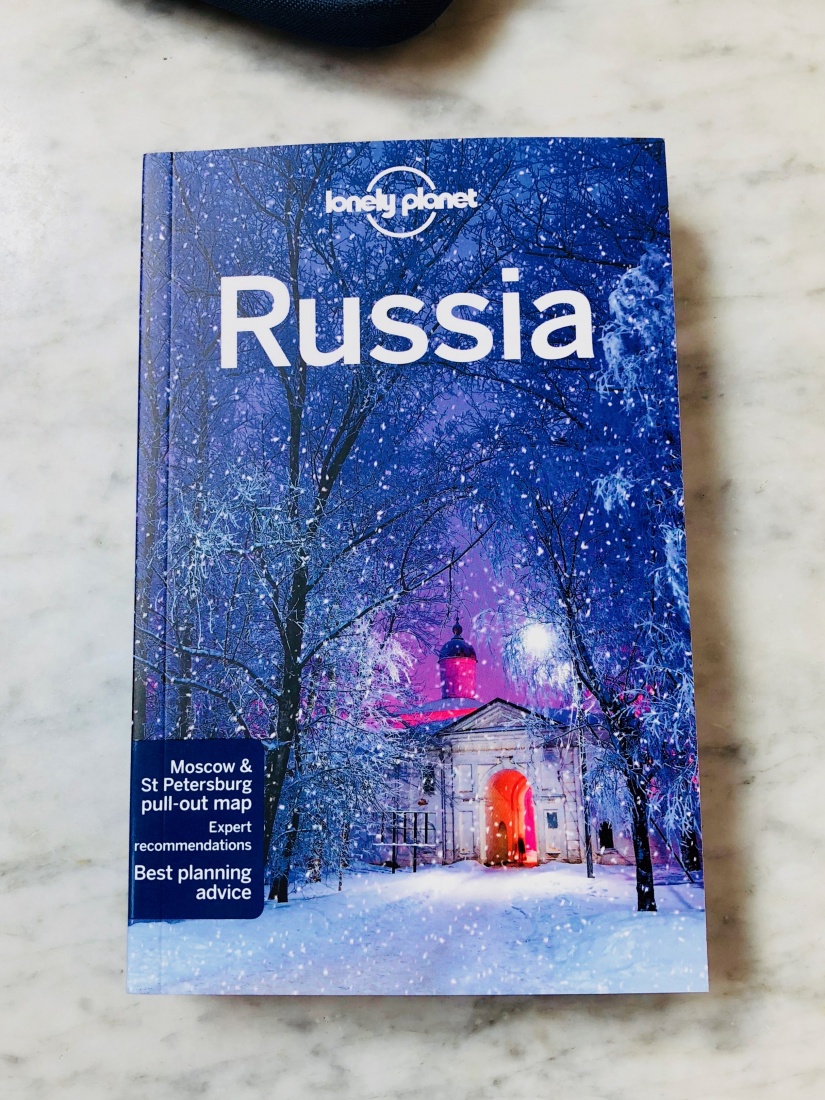

When I accepted a guidebook offer last year to research and write about Russia, I was excited to have the chance to visit and learn about a country I’d only ever seen as a tourist and that I remained fascinated by. The Czech Republic (then as Czechoslovakia) broke with Russia as part of a de facto political union, the Eastern bloc, in 1989, yet Russia continues to exert a strong influence on the country’s psyche – as indeed it does on all of the formerly Communist countries of Central & Eastern Europe.

Of course, I knew about Russian President Vladimir Putin and held no illusions concerning the guy. I realized he’s a bad actor, who runs criminal enterprises, threatens neighboring countries, and orders political opponents to be jailed or killed. Still, I was swayed in favor of the project – perhaps without ever consciously thinking about it – by ideas of international relations I learned way back in college and still hold dear today: cross-cultural contacts between people are good. Travel brings people together. Xenophobia thrives in isolation.

I was proud to be part of an effort to highlight a kind of “black sheep” nation in the belief that mostly good things could come out of it.

I only became aware that a kind of general PC, anti-Russia bias was creeping in after I returned home from Russia and started tweeting links to some of my photos and articles from the trip. The vast majority of the reactions I received to the tweets were positive, but occasionally someone would tweet back a reply such as (paraphrasing here): “I’d never go to Russia while Putin is president” or “traveling to a dictatorship only strengthens the dictator.” Wow, I thought, this is really a thing.

Apparently, the anti-Russia bias may even go deeper than a couple of cranks on Twitter. In an article earlier this year for Skift, titled “Why U.S. Travel Media Won’t Tell People to Visit Russia,” a former fellow writer at Lonely Planet, Robert Reid, pointed out that the editors of eight leading global travel publishers* had failed to include any reference to Russia whatsoever on their annual “Best of 2018” travel lists. Reid was careful to note that there was no direct evidence of bias, but remarked the omission was odd given the fact that Russia, this summer, hosts the FIFA World Cup 2018 football tournament, the world’s biggest sporting event focused on a single sport.

That’s right. According to Skift, none of the eight named a destination in Russia. And the New York Times even had 52 chances to do so, in their annual “52 Places to Go in 2018.” There must have been something in the Kool-Aid.

Reid wrote: “Travel is supposed to be the grand connector. Yet, whether consciously or not, the travel publishing world seems to be failing to seize a moment to champion what it always has championed — that travel helps reduce prejudice, bias, and bigotry.”

All this leaves me in the middle of a muddle, which I'll try to sort out here.

First, to answer the question set out in the title: “Is Travel a Political Act?” It’s clear, I think, the answer (on some level) is “yes.” The places travelers choose to visit, the businesses they patronize, and the money they spend, particularly in an autocratic country, can exert much the same impact on a place’s politics as they can on a country’s environment or culture. The onus falls mainly on visitors to learn and, where possible, to make informed choices.

Now, as to Hana’s idea for a travel publication or guidebook that would foster more politically aware travel, I still have strong reservations. I’m deeply uncomfortable with the idea of a nanny guidebook, and ultimately I believe it’s up to individual travelers themselves to make their own best decisions based on objective information. (I hope that doesn't mean I'm a Libertarian ...)

At the same time, though, I see the writing on the wall. In the past decade, travel publishers have become much more active in promoting ideas like environmental and cultural conservation. Guides, for example, now routinely warn readers against attractions, such as poorly run safaris or trained-animal acts, that put wildlife at risk, or against activities that could compromise forests, mountains, or barrier reefs. The results have been promising.

It’s not such a huge step to imagine someday that future travel articles might bake into the cake a subtle (or not so subtle) promotion of democratic practices and human rights as well. I’m not sure how it would all work, but it’s conceivable.

As for boycotting destinations or blacking them out – intentionally or not – I still believe that’s simply the wrong way to go (leaving out travel to countries that promote grievous crimes like genocide or human-trafficking). As they say, travelers visit people, not governments, and the potential benefits of travel, including seeing, learning and making friends, outweigh, for me, the possible hazards. And the converse is often true as well: not going simply strengthens the hand of bad actors. I see no good reason to skip travel to Russia (or Cuba, Belarus, Iran, or almost anywhere else) if that’s where your heart takes you.

And where would you draw the line, anyway? I offer this comic example to illustrate the challenges:

Scanning the New York Times list of “52 Places to Go in 2018,” I noticed that Prague pops up on the list at no. 39. That’s not unusual (Prague often makes it onto these kinds of lists these days). That is, until you consider the current make-up of the Czech government: a xenophobic, anti-immigrant, pro-Kremlin president and a former Communist-party-member prime minister, whose company has been accused by the European Union of embezzling subsidies. Maybe the Times isn’t totally up on Czech politics?

Both men were democratically elected (and that’s a significant difference), but it’s still very much a rogue’s gallery of governance – and, in my opinion, still far short of a good reason to pass up seeing Charles Bridge this summer.

*The eight travel publishers that, according to Skift, failed to include reference to Russia on their annual “Best of 2018” (or comparable) travel lists: New York Times, Lonely Planet, Conde Nast Traveler, Travel & Leisure, National Geographic Traveler, CNN, Afar, and Frommer’s.

Great post—I really enjoyed reading it. I think there are two ways to frame the idea of travel as a political act, though. You spoke very clearly about one, the question of whether visiting countries with oppressive regimes or terrible human rights records lends financial or implicit moral support to those regimes. (I’m ambivalent, but mostly don’t feel that visiting Myanmar or Russia implicates travelers in the regime’s choices, any more than the average Nicaraguan or Guatemalan holds me—an American—personally responsible for the CIA.)

In the context of spreading nationalism and populism, however, I think that a willingness to inhabit other cultures can become inherently political. Of course, not every all-inclusive trip to Cancun strikes a blow against “America First!”, but choosing cultural connection, openness, and a certain humility in the face of difference is and will remain politically significant.

My friend, Sarah, added this point of view on the politics of travel on Facebook:

“I’ve always tried to travel with my political consciousness (and conscience) active. When I traveled to Czechoslovakia in 1985 I stayed with the mother of a friend, visited various dissidents and attended an underground rock concert with Mejla Hlavsa. When I went to Russia 2009 I didn’t have the contacts to do that, but I stayed in hostels and rode Platzkard like ordinary Russians. I would love to have a guidebook to help me avoid contributing to the coffers of dictators and to direct me to places and activities that, if they don’t actually oppose the regime at least don’t directly support it. Of course given the realities of the way dictatorships impose themselves and intrude on citizens that may not be practical. Perhaps a private travel consultant would be more useful.”