Although Katrin and I both live in Prague and have for a long time, we don’t get the chance to meet very often. She’s busy with work and family stuff, and I travel too much. Earlier this summer, she sent me an invitation to an open house at the German Embassy in Prague, where she works. I was drowning in deadlines and couldn’t make it but suggested we meet up for lunch the following week.

She chose an upscale Italian place, Pastař, for us to meet, but I didn’t mind in the slightest. I’d been thinking for a while the restaurant might make a nice addition for a guidebook listing but hadn’t had the opportunity to try it. Besides, it was right across the street from my office.

So that’s what happened. We met, found a table, and started chatting. I’d barely had time to cut into my mozzarella di bufala when she dropped an unexpected conversational bomb: “You know, we’ve known each other now for 30 years.”

“Thirty years? No way. It couldn’t be anywhere near that long.”

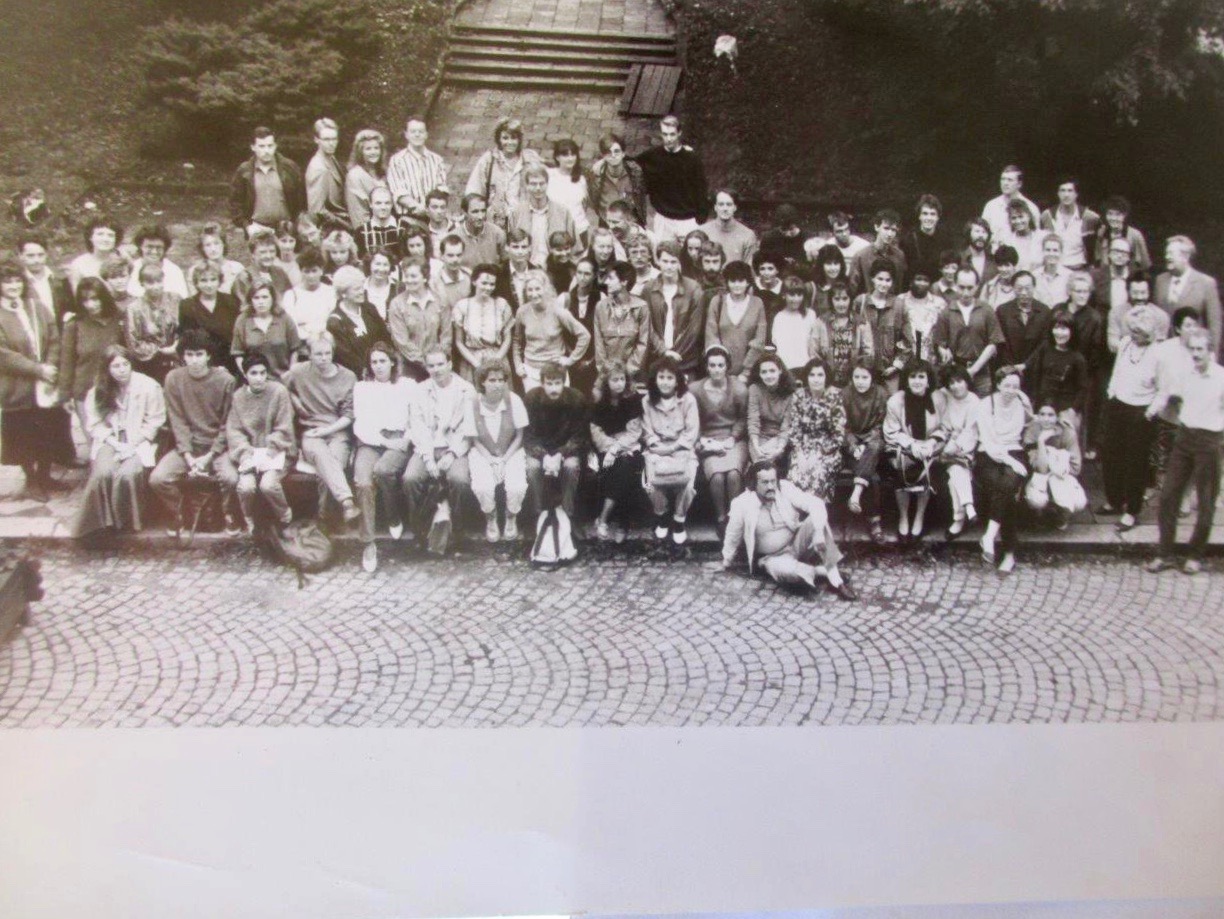

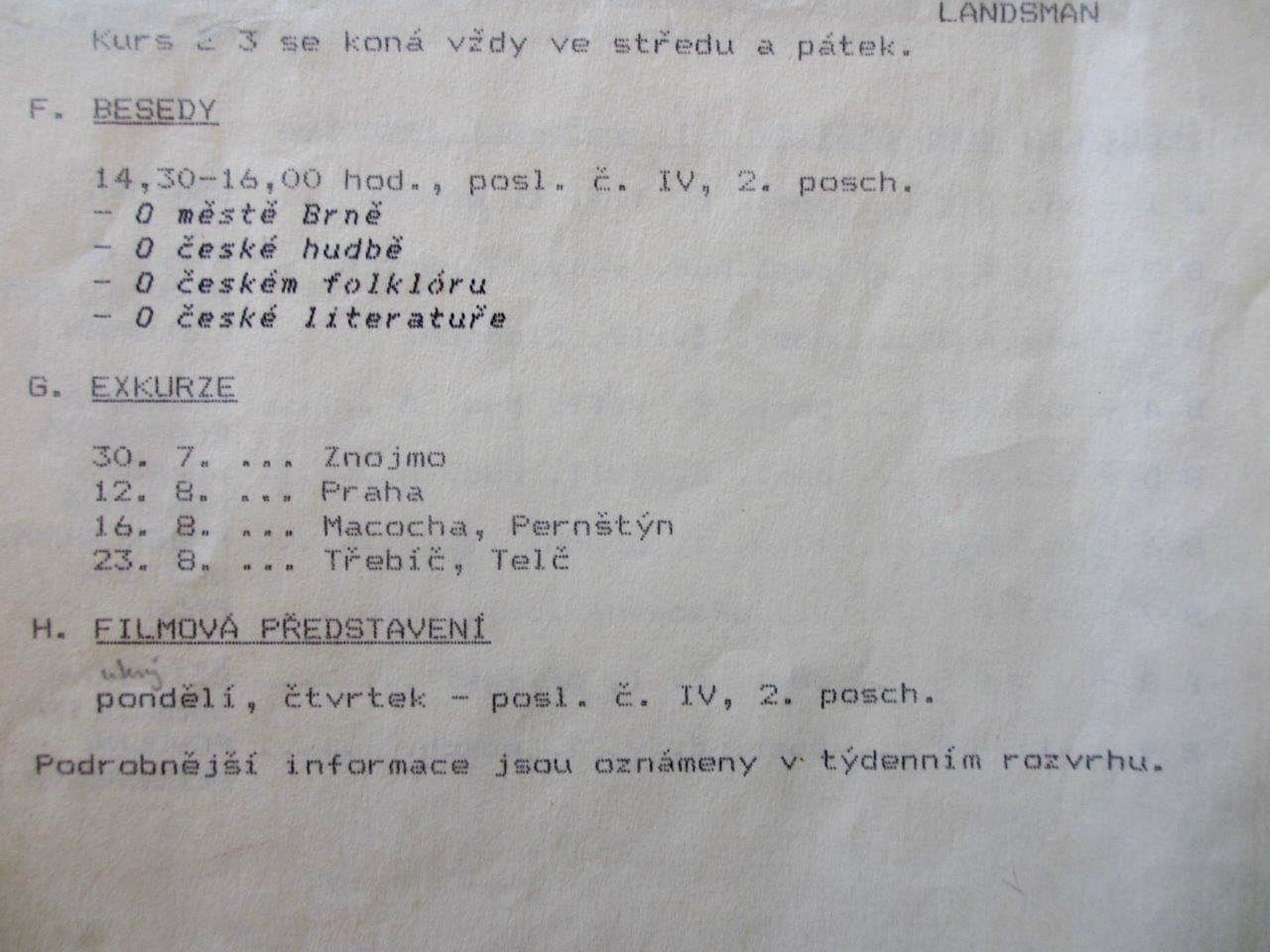

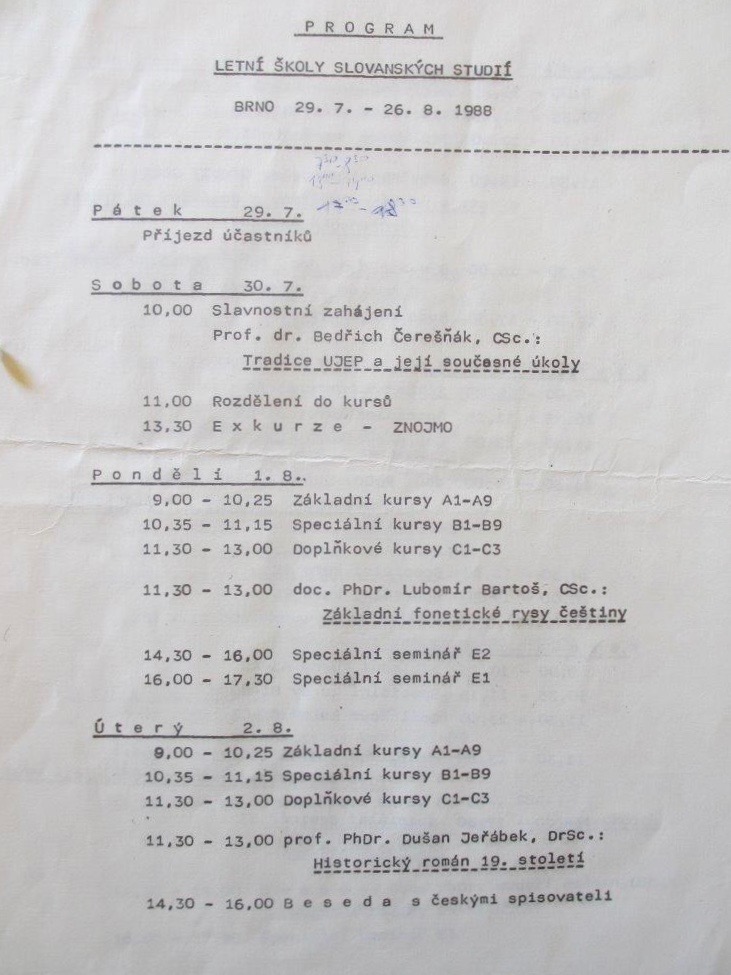

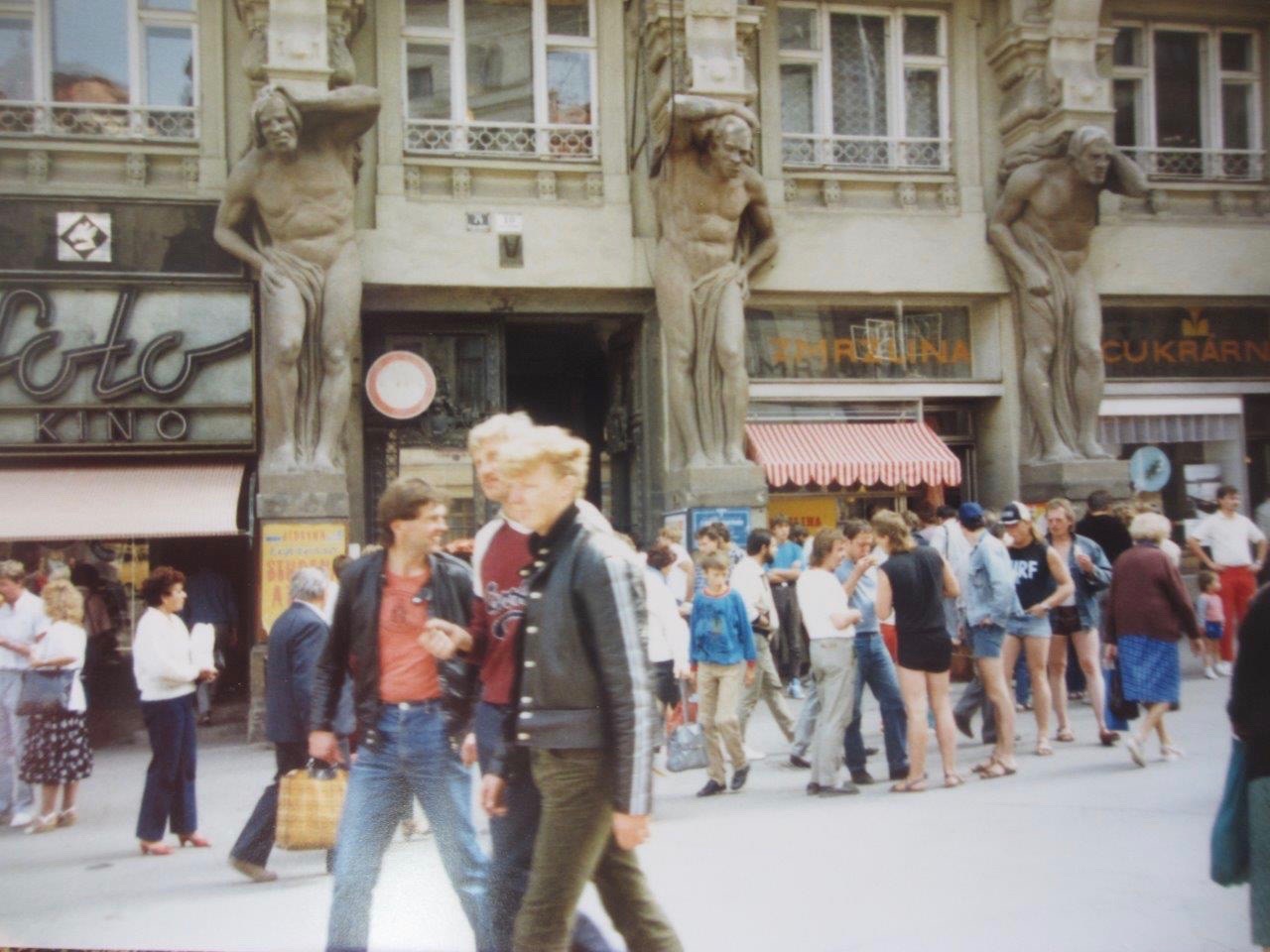

It turns out she was right. It was almost 30 years ago to the day from our lunch that Katrin and I were both Czech-language students at Brno’s summer school for foreigners: "Letní škola v Brně." She was one of several West German students attending the program that year, while I was the only American (if memory serves). Judging from the group photo (posted here), there were around 80 of us in all that year.

The idea behind the course was to spend a month focused on perfecting our (in my case, rudimentary) Czech-language skills. All of the participants lived together in a university dormitory, called the “Družba” ("Friendship" in Russian), conveniently located on a stern, featureless avenue called "Leninova" (named for Vladimir Lenin, of course). Classes were held in some of Brno’s university buildings nearby.

Over lunch, Katrin and I tried to recall our memories of the program and of our mutual friends from those days. She’s been better than me at keeping in touch with people, though both of us have lost contact with most of our fellow students. (If anyone is out there and is reading this, please give me a shout!)

Our conversation got me thinking again about that month in Brno. It was the longest continuous period, until that point, I’d ever stayed anywhere in the former Soviet bloc. I was excited to go, but equally excited to leave when it was over. The experience affected my impressions of Central and Eastern Europe back then and still shapes my thoughts about this part of the world. This post is about me trying to work out how.

By coincidence, a few weeks after our reunion lunch, I was planning a return trip through Moravia to attend a travel-writing conference (called TBEX) in Ostrava. The drive from Prague would take me through Brno, so I figured why not pair the trip with a stopover in the Moravian capital. I could carry out some guidebook research for Lonely Planet and spend time wandering around the city and reconnecting with my pre-Velvet Revolution self.

If you’ve read my earlier posts about the 1980s, you’ll know that in the summer of 1988 I was working as a journalist at the Vienna branch of a small publishing company called Business International. Part of my job was to cover Czechoslovakia, but my Czech was only good enough back then to scan the country’s statistical yearbook and catch a headline or two from the official communist newspaper: "Rudé právo." I’m not sure whose idea it was to send me to language camp in Brno, but I was happy to go and very much looking forward to learning more about the language and country.

The timing of the course, just a year or so away from the big historic changes, including Czechoslovakia's own Velvet Revolution, that would sweep communism out of Eastern Europe, in retrospect feels significant. It's true that communism was already on its last legs, but I'm pretty sure no one -- including me -- had any inkling of that at the time. The fact that Business International was willing to send me on and pay for a month-long course indicates that no one in my company, at least, expected any major political changes any time soon. Once I got to Brno and met the course's administrators and teachers, it was clear that no one on the other side of the line, either, was anticipating anything like a revolution.

Indeed, as strange as it seems now (with perfect hindsight of how everything would turn out), the odd division between East and West back then was accepted without question by both sides. It was perceived as being as normal and natural as the phases of the moon.

I had already started my working career and I was several years older than most of the program's other participants (who were still mostly college students). I thought that my party days were mostly behind me by that point, and I wasn’t sure what to expect. I got a taste of what was coming, though, right from the beginning -- at the Czechoslovak border -- after catching the bus in Vienna on a late-July morning for the trip up to Brno to start the program.

Border crossings were a lot more complicated back then than they are now. These days, borders in this part of Europe are wide open and buses sail right through. In 1988, however, we'd be crossing the Iron Curtain, and all of the cars and buses would have to stop for a thorough inspection. The whole thing could -- and often did -- take hours.

And so it was on that particular morning, the bus rumbled to a stop at the Austrian-Czechoslovak border, and we prepared to get off to show our passports and answer questions from stern-looking officials about why were coming and what we planned to do. Before lining up for the long wait at the customs inspection, I wandered over first to the restroom. As I walked in, I was surprised to see a guy standing in front of me and sweating profusely. He was a bit younger than me, obviously foreign, and pretty worked up about something.

“Do you think they’re going to search us?” he asked me (in English, with a British accent).

“I don’t think so," I said, "but I’m not sure." And then I asked him why.

At that point he showed me a small amount of grass (or maybe it was hash?) that he’d rolled up in some aluminum foil with the idea that he was going to take it with him across the border. He was suddenly, urgently, looking for a way to get rid of it.

I told him I didn't think it was a good idea to try to smuggle anything into Czechoslovakia, and I believe he ended up flushing it down the toilet. Whatever he did, though, he never got caught. How do I know? Once we got to our dormitory in Brno and received our room assignments, I discovered that I'd been talking to my roommate for the duration of the program. (I won’t mention his name to spare him the embarrassment, but he turned out to be a nice guy.)

I have an on-again, off-again love affair with the Czech language. After so many years and so many lessons, to my eternal shame, I’m proficient but not fluent. It’s not that I’m terrible with languages (I managed to pick up German fairly quickly in Vienna, and French as a student in Luxembourg), but for some reason I have a block with Czech.

What I am fluent in, though, is Czech folk songs (or, more precisely, Moravian folk songs), and for that I owe my gratitude to that summer school in Brno. While our mornings at the school were taken up with hours of rigid instruction in Czech grammar; in the afternoons, we mostly learned and sang folk songs.

Czechs and Slovaks will know at least a couple of my favorite songs by heart, but they're not particularly well known outside the former Czechoslovakia: “Vínečko bile” ("My little white wine …") and “Čerešničky, čerešničky” ("Cherries …" ). (Follow the links to YouTube videos to hear how the songs are supposed to sound.)

I can’t tell you how many times over the years this peculiar knowledge of Moravian folk music has served me well, particularly when out with friends or on a date in a traditional pub or restaurant. Whether we were in Bohemia, Moravia or Slovakia, the scene would inevitably unfold in the same way: we'd order our food and drink and the first strains of violin music from a “gypsy” band performing that night would suddenly waft over the table. Not long after that, the guys in the band would be standing at the table, hat in hand, asking for a song request -- and naturally expecting a tip.

Thanks to summer school, what could have been a series of fraught encounters over the years, instead, became like child’s play. I always had (and still have) a ready-made list of request tunes in my head, and can even sing along if necessary.

My decision to stop over in Brno on my way to the travel-writing conference in Ostrava had been a good one and a flood of memories came back. I rode my bike out to our old dormitory, which was just a few hundred meters north of the Hotel Continental, where I was staying. The dorm is still standing (and still housing students for the summer-language program; the 2018 edition coincidentally started the week of my visit). It's no longer called the "Družba," which sounds way too communist, and the street has been renamed "Kounicova," after a Czech count from the 19th century. As for Lenin, there were no signs of him anywhere to be found.

One of the first things I noticed was the exterior of the dormitory had gotten a fresh (and garish) coat of paint sometime in the past decade. No matter how cheerful the newish red, yellow and orange façade appeared, however, the pervasive institutional drabness (that I remembered so fondly) remained intact. You could sense it immediately in the overgrown trees and burnt-out patches of grass in the front of the building. I took a peek inside the building and got a whiff of the communist-era linoleum cleaner they must still be using, which prompted another rush of memories.

Over the years, whenever I would think back on that old dorm, my mind would drift hazily (like recalling the outlines of a dream) to a small beer garden located behind the building. In my recollection, the place had a few plain tables and a string of outdoor lights, similar to what you might find at a campground. I was curious whether the place really existed or merely something my mind invented. I took a walk around the back of the dormitory and was relieved to find the “Plzeňský Dvůr” -- exactly the kind of make-shift, beer-drinking joint I’d hoped to see. The tables, built on steady concrete, had obviously been around for more than 30 years.

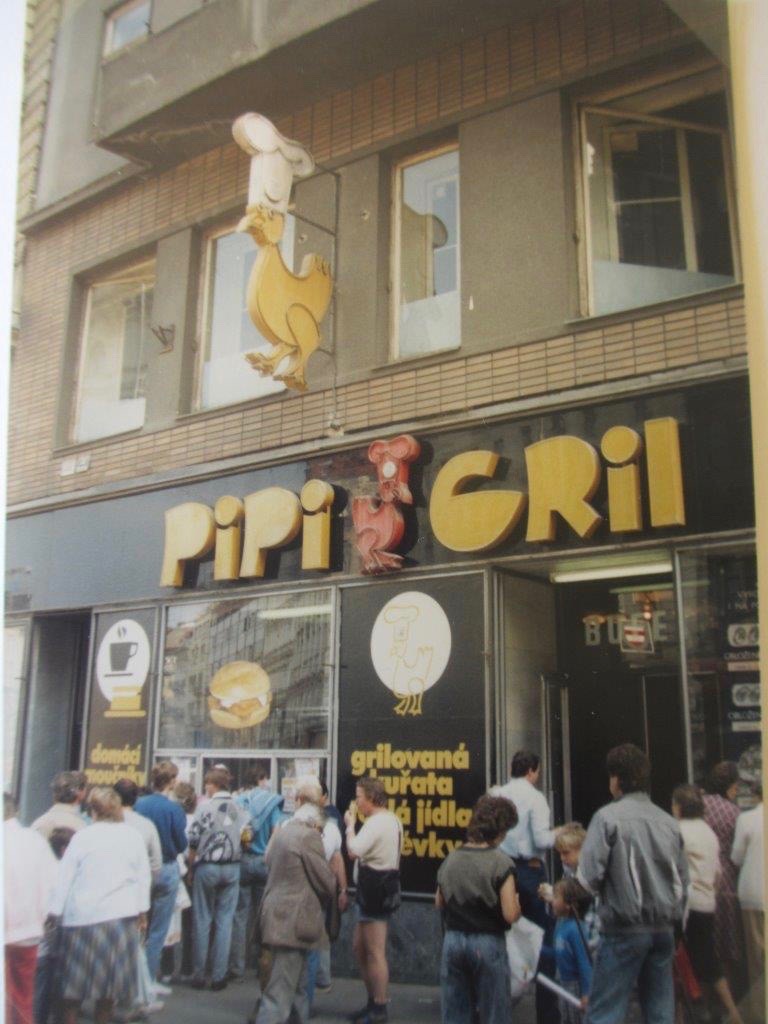

Afterward, I cycled around the city, which sparked off more long-buried impressions: drinking at the tacky outdoor terraces up near the top of Špilberk Castle, hanging out at a popular milk-bar called "Sputnik" (which later, sadly, became a KFC), and snacking on what locals back then euphemistically referred to as “pizza” on the terrace of the Continental Hotel (the very hotel I stayed in on that trip -- but alas the pizza place was long gone).

Slowly, over the next couple of days, a different kind of recollection began to take shape. This was not a specific memory of anything particularly in Brno, but rather more of something within me. Back in 1988, we'd had a lot fun in our classes and nights out in the pub, but my main memory from Brno that summer hadn't been excitement. It was more a feeling of isolation.

We had a surprising amount of free time at the school (or at least I did), and I remember taking long walks on my own around Brno's older, poorer neighborhoods to the south and east of the center. From a ridge, I'd look out onto the dusty, empty streets in the distance and try to pick up a vibe -- any vibe -- or feeling of familiarity. All I'd get was stillness. This isn't a knock on Brno (which is a great place to spend time), and obviously there was a lot more going on back then than I was aware of. My antenna simply wasn't tuned to the right frequency, and I lacked the experiences needed to inform my perceptions.

In those moments, I would feel both cut off from my home life in Vienna and hyper aware of myself -- feelings made stronger by the close proximity of the Iron Curtain (and me being on the other side of it). The effect was an exaggerated sense of apartness or otherness that seemed to heighten my own sense of existence. Solo travelers will probably have an idea of what I mean here. I experienced those feelings strongly in the summer of 1988 -- and maybe for the first time in my life. Thirty years later, while reflecting on those old days in Brno, those sensations came rushing back in more-muted form all over again.

(Scroll past the map for more photos. I wrote about Brno's heritage of modern architecture in an earlier post. Find it here.)

This was such an interesting read, Mark, especially as I find myself doing a language course in Berlin at the moment. I never knew exactly what Družba meant, but in ?eské Bud?jovice it’s the name of a shopping complex barely hanging in there, but still on one of the city’s main drags.

And yes, I know all too well that hyper existance feeling… I believe I even felt this way today. I seem to also have a similar block with Czech that doesn’t exist for me with other languages. The thought of someday passing a B1 exam seems like a pipe dream!

Thank you, Cynthia, and I’m really happy you liked the story. Good luck with Czech — it usually doesn’t take 30 years 🙂

Thank you, Mark.

I visit Brno a couple of times per year for work, and it is so interesting to read about what it was like before The Change. I always stay at the Continental as it is close to the office. I haven’t gone too far up Kounicova or out to the ‘burbs yet, but will check it out in my next visit. Brno is definitely worth a visit or day trip, it’s quite nice! 🙂

The Continental is pretty cool these days. Still very recognizable, but I cannot remember now where the pizza terrace was 🙂 I think it was where the outdoor coffee place is now. Kounicova still has lots of police and army buildings on it. It’s changed, but surprisingly not all that much. Thanks for leaving a comment! Mark