I still consider 1989 as the most important year of my life. For one thing, it marked a significant inflection point in my career. I’d chosen "Eastern European" studies at graduate school in the mid-1980s and had been steeped in all that textbook analysis back then of Soviet-led political systems and economies. I’d also worked as a journalist in the field for a few years, so I’d become quite invested in the permanent division of Europe into East and West.

When the regimes fell, with seemingly no warning, just about everything I’d learned up until that point was suddenly rendered useless. Like everyone else, I was caught up on the fly having to understand and interpret a historic transition -- from Soviet-style communism to democracy and free-market capitalism -- that had never been attempted before on this scale.

It was also the year my father passed away, just shy of his 52nd birthday and in the midst of all of that change. When I think back on those tumultuous times, the euphoria I felt at seeing those autocratic, arthritic regimes of the old Eastern bloc collapse is always tempered by sadder memories of returning home that summer to be with my family. It’d been a life-altering year, both for Europe and for me.

I’ve never written specifically on 1989 for this blog, so maybe it’s time, on the 30th anniversary, for a few words about what it was like back then to watch those unreal events unfold in real time and not know from week to week what was going to happen next. I’d also like to puncture here a couple of myths about those days: that the changes were both foreseeable and inevitable. As someone who was there, I can tell you that neither of those is true.

In 1989, I was working as a journalist in Vienna for a small publishing outfit called Business International (BI), which was affiliated with Britain's Economist Group. From our office at the eastern end of Austria, just 40 miles west of Bratislava, a small team of around 10 journalists and analysts would read over news reports coming across the Iron Curtain in order to help our readers and clients, mainly large Western corporations, to understand the political and economic environment there.

Our flagship publication was a weekly newsletter called “Business Eastern Europe.” For most of 1989, I was a reporter for the newsletter and responsible for covering Czechoslovakia; at the end of that year, I became the publication’s editor. We were unique at the time among Western publications for our specific focus on Eastern Europe, and the communist regimes were convinced that we were all spies. If we were in fact spies, no one ever told me, and the Central Intelligence Agency owes me some back pay. (I’ve posted earlier stories on this blog about some of my strange spy-v-spy reporting trips to Czechoslovakia before 1989, and about my Czech translator/fixer “Arnold,” who turned out to be a real spy.)

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, it seems inevitable now that the hulking Eastern bloc would eventually collapse under its own weight. It’s somehow taken for granted that those sclerotic Soviet-led regimes would never have been able to keep up with the more dynamic societies of Western Europe and the United States. After all, back in the day, those repressive governments would enforce their rigid censorship restrictions by confiscating dissenters’ typewriters. How would they ever have coped with the ubiquitous mobile-phone networks and Internet connections that in 1989 were just a few years down the road?

That may be true, but I can say with certainty that no one (or nearly no one) at the time saw the revolutions coming. At BI, it was our job -- our bread and butter -- to anticipate and predict historic events like the collapse of communism, but even then as we squinted and stared at the regimes across the border, we couldn’t have said with any confidence, day-by-day, what was going to happen next.

When I think back on our kitchen conversations in Vienna throughout that year -- BI was headquartered in an old apartment and we actually did have a kitchen -- the conjecture inevitably turned on the personality of then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev had risen to power in the mid-1980s by promoting political and economic reform in Eastern Europe centered on his ideas of glasnost and perestroika ("transparency" and "economic restructuring").

The big question at the time, though, was whether he was sincere in his efforts (or powerful enough) to reform the communist system, or was simply inventing new wrinkles to maintain Soviet control. If he was indeed sincere, was he willing to risk Soviet domination over Eastern Europe in order to implement those ideas? Our office appeared to be split on the answers. While we all hoped for the best, some of us believed in Gorbachev’s intentions (or abilities) and others did not. No one knew for certain.

To be sure, Gorbachev had so far by then defied historical logic. In the past, it had always been the Soviet Union that would step in to impose communist orthodoxy on its reluctant Eastern bloc allies, as it did in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. This time around, however, it was the Soviet Union that was pushing for reform, and, ironically, the leaders of many of the Eastern satellites who were resisting.

The biggest impediment to real political change in the region was the lack of any organized opposition to communist rule. With the exception of Poland and the Solidarity trade union, none of the other countries had any credible political opposition. Sure, Czechoslovakia had a handful of courageous dissidents, and there was some small church-led opposition groups in East Germany and Romania, but the question remained open as to who or what could step in to force the old leaders out and then wake up the next day to run the trains, schools and factories? We were about to get a big lesson in people power later in the year, but at the time, our biggest fear was that it would all end in bloodshed.

When I wrote above that no one could have predicted which way the 1989 revolutions would go, I was thinking in particular of my own botched fact-finding trip to Czechoslovakia in early-November that year. By that time, Hungary and Poland had already taken steps to reform their systems and leave the Eastern bloc, and protests were gathering pace in East Germany. The mood in Berlin was restive, and BI wanted me to gauge public sentiment in Prague.

My trip happened to coincide with the second big wave of East Germans who were coming to Prague with the hope of circumventing the Berlin Wall and emigrating to the West. A month earlier, on September 30, West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher had come to Prague and electrified an initial wave of East Germans who had gathered in the city by granting them passage to West Germany in specially sealed trains. The wall was still standing, though it was clearly fraying across the rest of the bloc.

During my Prague trip, I interviewed many Czechs on Wenceslas Square and at other points around the city to ask them if they believed their own hard-line regime would ever crack. The answer, to the last man and woman (and in spite of the presence of thousands of East Germans in the city at the time), was always the same: it could never happen here.

I dutifully returned to Vienna and wrote up an article for "Business Eastern Europe" that dismissed any notion that political change in Czechoslovakia was imminent (thankfully, I can no longer find a copy of that article). In fairness to my colleagues at Business International, I can’t recall any of them writing something that turned out to be so wildly incorrect. Just a couple of days after my visit, the Berlin Wall collapsed. Czechoslovakia's own Velvet Revolution -- that would eventually install as president the dissident playwright Václav Havel -- started up just 11 days later.

While I’m trying to debunk myths surrounding the events of 1989, I’d like to poke a hole in the idea that the revolutions were some kind of collective act of will. When we look back on those days from the present, it’s easy to imagine that the whole of Central and Eastern Europe simply rose up as one to throw off their oppressors. In fact, the anticommunist revolutions unfolded over the course of the year in a series of separate episodes that might better be understood as isolated acts of defiance. There was, in fact, very little coordination. Each country took a different tack, and any one of those actions could have been stopped in its tracks. There was plenty of chance and luck built into the model.

The fall of communism began with a whimper (not a bang) in June of that year when Poland held its first semi-free parliamentary elections since at least the end of World War II. That vote led to a humiliating defeat for the ruling communist party (the Polish United Workers Party) and the appointment later that summer of Eastern Europe’s first non=communist prime minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki. The reaction from Moscow was relatively muted, even though documents would surface later suggesting that Gorbachev had come under strong pressure from harder-line Eastern bloc leaders, like Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu, to intervene militarily.

A few weeks later, on June 27, the leaders of Hungary and Austria met in an abandoned field to symbolically cut the barbed wire of the Iron Curtain that had separated their countries since nearly the end of World War II. I remember watching the spectacle at the time as it unfolded on Austrian television but not giving it much significance. I figured the Hungarians would simply replace the wire with a more sophisticated electronic system.

None of us realized at the time, though, that this episode had been carefully choreographed in advance between Gorbachev and then-Hungarian Prime Minister Miklós Németh, and that the opening was more or less legitimate. The Soviets had given the Hungarians their private assurances that whatever happened, there would be no repeat of 1956. Németh later told the French news agency, AFP, about that agreement and its consequences here.

The implications, though, were certainly not lost on people living on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain as they began to calculate that if they could just make it to Hungary, they could eventually make it to the West. The simple act of cutting some barbed wire had set the entire train in motion.

The months of July and August that year marked a major turning point in the anticommunist revolutions and, looking back, the entire postwar history of Europe. Events in Poland and Hungary had clearly divided the bloc into two camps: the reformers and the hard-liners. Opposed to Hungary and Poland, on the other side, were the far more conservative (and much less enthusiastic about glasnost and perestroika) regimes of East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Romania.

The tension was thick that summer in our BI offices in Vienna. The movement toward reform in the Eastern bloc was clearly accelerating, yet it was hard to imagine any outcome that didn’t involve blood in the streets. Would ultra-conservative leaders like Erich Honecker in East Germany, Miloš Jakeš in Czechoslovakia or Ceaușescu in Romania relinquish power without a fight? That outcome seemed highly unlikely.

The Kremlin, of course, could have stopped the reforms at any moment, and all eyes turned once again toward Gorbachev. Instead of putting the brakes on the reform momentum, though, at every turn (whether he intended to or not), he appeared to give the reformers a green light.

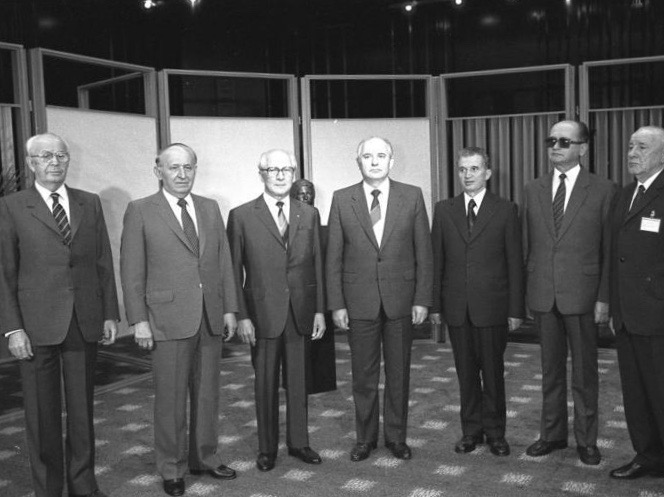

Addressing a tense, divided meeting of Warsaw Pact leaders in the Romanian capital, Bucharest, in early July, Gorbachev told the group that there was a “new spirit” in the alliance. In so many words (and couched in his trademark diplomatic double-speak), he appeared to say that the member states would now be free to pursue their own paths to solve their own national problems (without fear of Soviet military intervention).

Oh, to be a fly on the wall of Bucharest's presidential palace to see the ashen looks on the faces of the hard-liners, including host Ceaușescu himself. Whatever would happen next, it was becoming clearer from Gorbachev’s own words that the Soviet Union would not call in the tanks to prevent the Eastern bloc from splitting apart.

Though the most dramatic acts of that year -- the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, and Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu’s televised execution before a firing squad on Christmas Day -- were yet to come, those events represented perhaps merely the denouement following from that Bucharest conference. Without the implied threat of Soviet military intervention, each of the regimes was suddenly on its own to fend for itself and to grapple with the very difficult issue of whether it was willing to kill its own citizens to stay in power.

This blog post has already gone way over-length (if you're still with me, thank you), so I’ll cut to the chase. To their credit -- whether they consciously decided not to use bullets or they simply lost their nerve -- the leaders of most of the Eastern bloc countries did not resist.

In September, the Hungarian government, after some serious hand-wringing, decided to allow a group of thousands of East Germans who had gathered there to cross the border into Austria (and the West) in an event that’s now referred to as the “Pan European Picnic.” That act was widely viewed as a final test of Gorbachev’s promise not to intervene, and true to his assurances, the Soviets didn’t react. A little later, Genscher came to Prague and granted free passage to the west for thousands more East Germans.

Emboldened by those events, hundreds of thousands of people came onto the streets in early November in East Berlin and later that same month in Prague (and cities around Czechoslovakia) to demand that the communist regimes step down. The transitions were largely peaceful and the “Fall of the Wall” and “Velvet Revolution” continue to inspire us to this day. Bulgaria's communist government fell without major violence at around this same time.

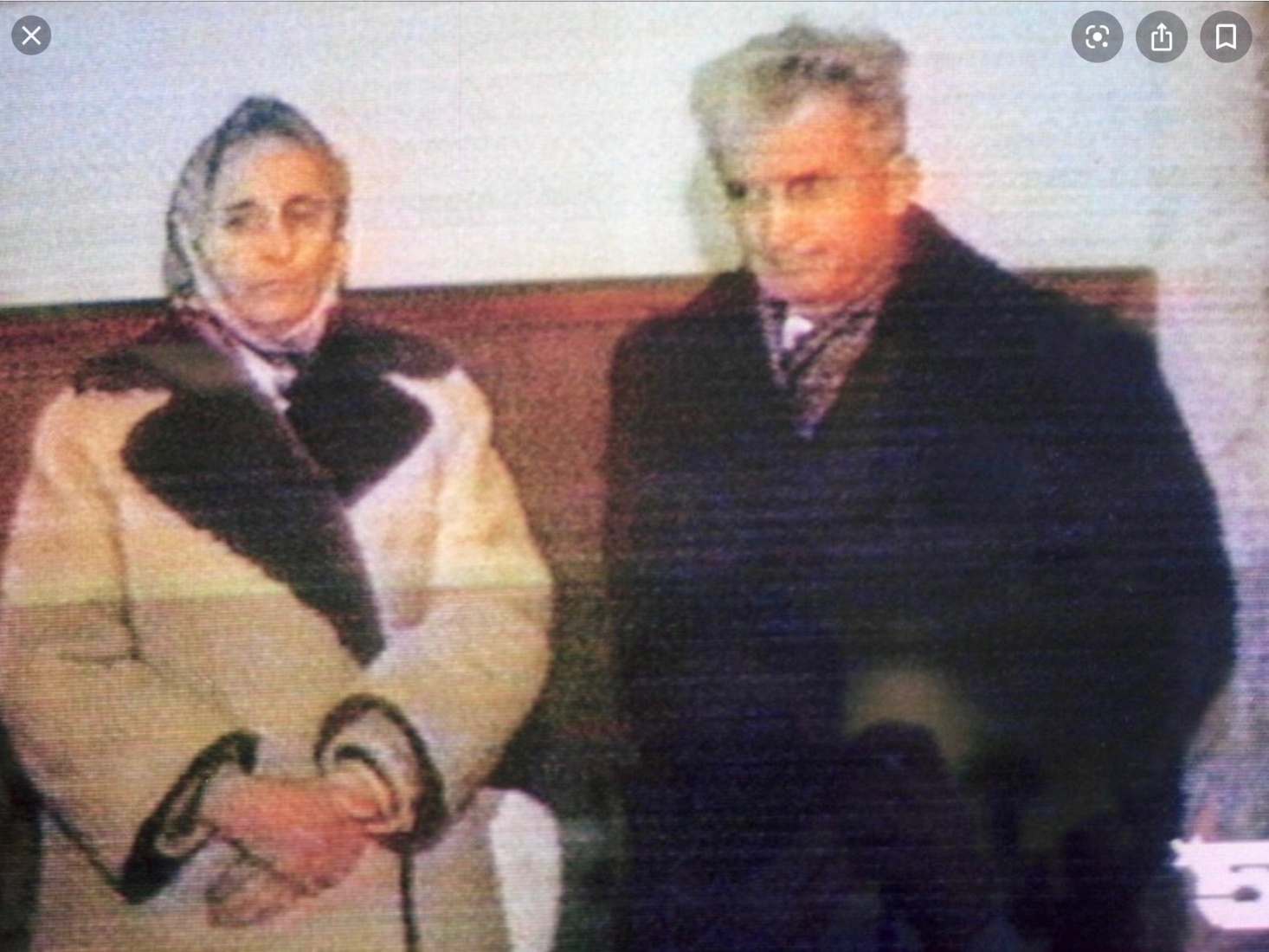

It was only in Romania where historians were offered a chilling “counterfactual” scenario of what would happen if a dictatorship attempted to use force on its people without the implied threat of Soviet military support -- and that didn’t end well. In mid-December, anti-Ceaușescu protests started up in the western Romanian city of Timișoara and soon spread to other places, including Bucharest.

It took just a little over a week for Ceaușescu and his wife Elena to be captured, tried by an ad-hoc tribunal and executed by firing squad. More than 1,000 people died in that bloody transfer of power, and it’s probably fair to say that the violence there set Romania back at least a decade.

Very interesting, too long? Not at all.

Thanks for sharing your insights.

Very interesting and definitely not long at all.

Thanks for sharing!

fascinating! So interesting to hear the recap from your point of view. No way it’s too long. I was glued.

Love your viewpoint of this heady time. I was in Berlin when the Wall fell.

I remember October 1989 as the most tense time for myself personally. It was at this point that Gorbachev had to give the word or “the sign” to the DDR regime that Moscow was going/not going to intervene if the East Berlin regime was in serious jeopardy. When Gorbachev’s sign was that the USSR was not going to intervene, then I knew that major bloodshed was going to be averted, that E. Berlin would fall eventually, that Poland was ultimately safe after its eventful 1989, and the rest of the system might crumble. I did feel nervous in November 1989 because I wondered if the Czech regime would put up a fight, and there would be bloodshed practically at our doorsteps in Vienna. Happily that did not occur. But I remember looking out my big windows on Schwindgasse out into the Vienna November gloom and seriously wondering. The creepiest moment was December 1989 when I was flipping the radio dial one Sunday afternoon and got a Romanian station. It was during Timisoara, and I couldn’t understand a thing. But I knew that there was a universe between me in my apartment on Schwindgasse and that radio announcer in Romania.

One sort of poignant memory I have was early-ish in September 1989, in the 3rd District in Vienna. Before work one morning I was going to the Soviet Embassy to apply for a visa or pick up a ready visa. Wasn’t the West German Embassy somewhere in the 3rd District? It had to be, because I walked by it and the big “travelers’ aid” station they had set up in front of their building to help incoming DDR citizens who were crossing over in droves from Hungary every day. When I walked by the building, there was only this one dazed young woman, very blond, tall, thin, and totally dressed in DDR clothes (maroon sweater and dark brown slacks, cheap yarn/material for both) with messy hair like she hadn’t combed it that morning, who was standing in front of the Embassy, by herself, arms folded close to her chest, just walking small steps and staring into the distance. I was struck forever by her dazed look. She looked absolutely like she had just taken the most important step in her life thus far.

Does anyone remember ORF breaking into its evening program on November 9, 1989 and announcing the Berlin Wall had been penetrated? I remember it quite well. My German was good enough to understand just about anything at that point, but I was convinced that I had misunderstood the excited announcer’s message. He kept repeating the news, over and over again, and I ended up standing by my stereo, ear right to a speaker, still convinced I hadn’t understood the news correctly. What a night.

November 17, 1989, I recall how everyone knew that events were going to boil over in Prague at any moment. It was a gloomy November Friday, and I recall visiting briefly earlier in the day with a couple of Western journalists who were getting on the train that day to travel up to Prague for what was expected to be a “hot” weekend. There was an ominous feel to things that morning, even though EE was lost to the Soviets, and the Czechoslovak leadership had to know it. I remember thinking the Czechs were cowards, as Poland, Hungary and even the DDR were lost to the Soviets, and the CSSR still hadn’t truly rebelled yet.

‘Czechia’ was chosen as the English short form equivalent of ?esko, Tschechien and Tsjechië, however it sounds ridiculous and nobody here likes or uses it.

We are called the Czech Republic, NOT Czechia! No one likes it, no one asked us, no one except Google and daft Americans uses it!

C Z E C H R E P U B L I C

Andrew, thanks for reading and leaving a comment, but that’s simply not true. Many people use Czechia these days, and Google uses it on its maps to designate Czech Republic. In any event, I was just making a joke. I am perfectly happy with Czechia or Czech Republic.

Dear readers,

I published a link to this story on my Facebook author page (www.facebook.com/markbakerwriter/) and the post generated an unexpected discussion concerning the name ‘Czechia’ for referring to the ‘Czech Republic’.

That wasn’t my intention at all with the blog post, but it does present a useful opportunity to discuss the name. As many of you probably know, it’s a relatively recent change and was implemented to give people a friendlier, more accessible way of addressing the Czech Republic. Both names are considered to be ‘official’ and interchangeable.

It took me a little bit of time to adjust to the new name, but I like and will start using it more in the future.

To give you idea of the FB discussion, I’ve copied a bit of it here below:

Andrew C.D. : Czechia was chosen as the English short form equivalent of ?esko, Tschechien and Tsjechië, however it sounds ridiculous and nobody here likes or uses it. We are called the Czech Republic, NOT Czechia! No one likes it, no one asked us, no one except Google and daft Americans uses it!

C Z E C H R E P U B L I C

Jimmy V.T: Actually, it was a daft American translator (Michael Heim) who was asked by Havel to name the country in English, and he came up with ‘Czech Republic.’ It’s been the Czechs themselves that have brought back Czechia, though that is often used geographically rather than politically.

Kim S.: But Czechia/Cesko is only Bohemia. It does not encompass Silesia or Moravia. Silesians/Moravians take offense at Cesko/Czechia.

Mark Baker: Do they?? I’m not sure. Google uses ‘Czechia’ now on its maps to designate the entire country.

Kim S.: We were talking about it today in our students’ orientation and my Ostrava colleague vehemently opposed the English usage of Czechia because of this.

Mark Baker: You might be right. I have never heard that objection before. How, though, is ‘Czech Republic’ better?

Veronika B.: Not true. Czechia/?esko is supposed to encompass Bohemia/?echy together with Moravia/Morava and Silesia/Slezsko. It was so also under ?esko-Slovensko (Czecho-Slovakia). The same way the adjective Czech/?eský refers to Bohemia/Moravia/Silesian altogether. It is nonetheless true that especially the Czech word ?esko does not sound very nice. Czechia is somewhat better.

I was in Berlin in 1989 as an exchange student, and I know things were “heating up” there throughout the fall, but I know no one could have predicted the events of November 9, 1989, much less the Velvet Revolution that happened the following week. What a time it was. Listening to your podcast about your experience in ’89 gave me goosebumps; I remembered how I felt during those heady days in November, 1989.

Thank you Gillian! It was fun to write and try to remember that chilling feeling all over again!

Mark,

What a wonderful personal history. You document your experiences beautifully. A friend and I spent three weeks in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland in spring 1984. No way would have I predicted what would happen just five short years later. I remember telling my buddy, Greg, that the Czechs still seemed traumatized by the events of 1968 and paralyzed by the Soviet Union. In the mid-1980s, Prague seemed joyless and gray compared to what it would become in the early 1990s. You are correct; almost nobody foresaw the collapse of the Iron Curtain until it suddenly came crashing down. Great piece

I’ve read a lot about 1989 so very interested in the subject although I don’t claim to be a scholar of it in any way. This post seemed to encapsulate all the truths without any of the myths and bluster, I hope it gets shared widely. I loved reading it and didn’t want it to end, as opposed to being too long. Thank you.