When I tell someone I once worked for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, that person’s reaction depends on where they’re from. People from Eastern Europe or the former USSR are invariably impressed and immediately start telling me heartwarming stories of how family members would huddle around hidden receivers and listen to the broadcasts at barely audible volumes (so their neighbors couldn’t hear). Others, mainly older Americans who remember those classic, haunting RFE/RL television ads from the 1960s and ‘70s, will usually chuckle and say something like, “Wow, Radio Free Europe still exists?” Many people apparently assumed that after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, RFE/RL simply packed up and shut down. Occasionally, though, someone will raise a skeptical eyebrow and ask: “Wasn’t RFE/RL funded by the CIA?”

That last reaction always saddens me a little because I think it reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the radio’s role that persists to this day. While it’s true both Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty – which began as separate stations -- emerged out of organizations covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency, any involvement of U.S. intelligence ended in the 1970s. Indeed, neither radio station was conceived to promote the interests of the United States (such as, for example, U.S.-funded Voice of America). The model for both stations, instead, was RIAS (Rundfunk im Amerikanischen Sektor), the West Berlin-based radio of American occupation forces in Germany after World War II. RIAS broadcast in German to audiences in both West and East Berlin and in Soviet-occupied East Germany. It functioned, more or less, as a typical commercial American radio station and was hugely popular on both sides of the Iron Curtain for precisely that reason.

Radio Free Europe was established to create similar “surrogate” free stations to broadcast to the Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe, such as Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Radio Liberty, for its part, broadcast directly to the Soviet Union. Both stations enjoyed great success from their base in Munich. They merged in the ‘70s (leaving us with today’s relatively cumbersome acronym of “RFE/RL”). In 1995, at the invitation of then-Czech President Václav Havel, the combined radio moved its HQ from Munich to Prague.

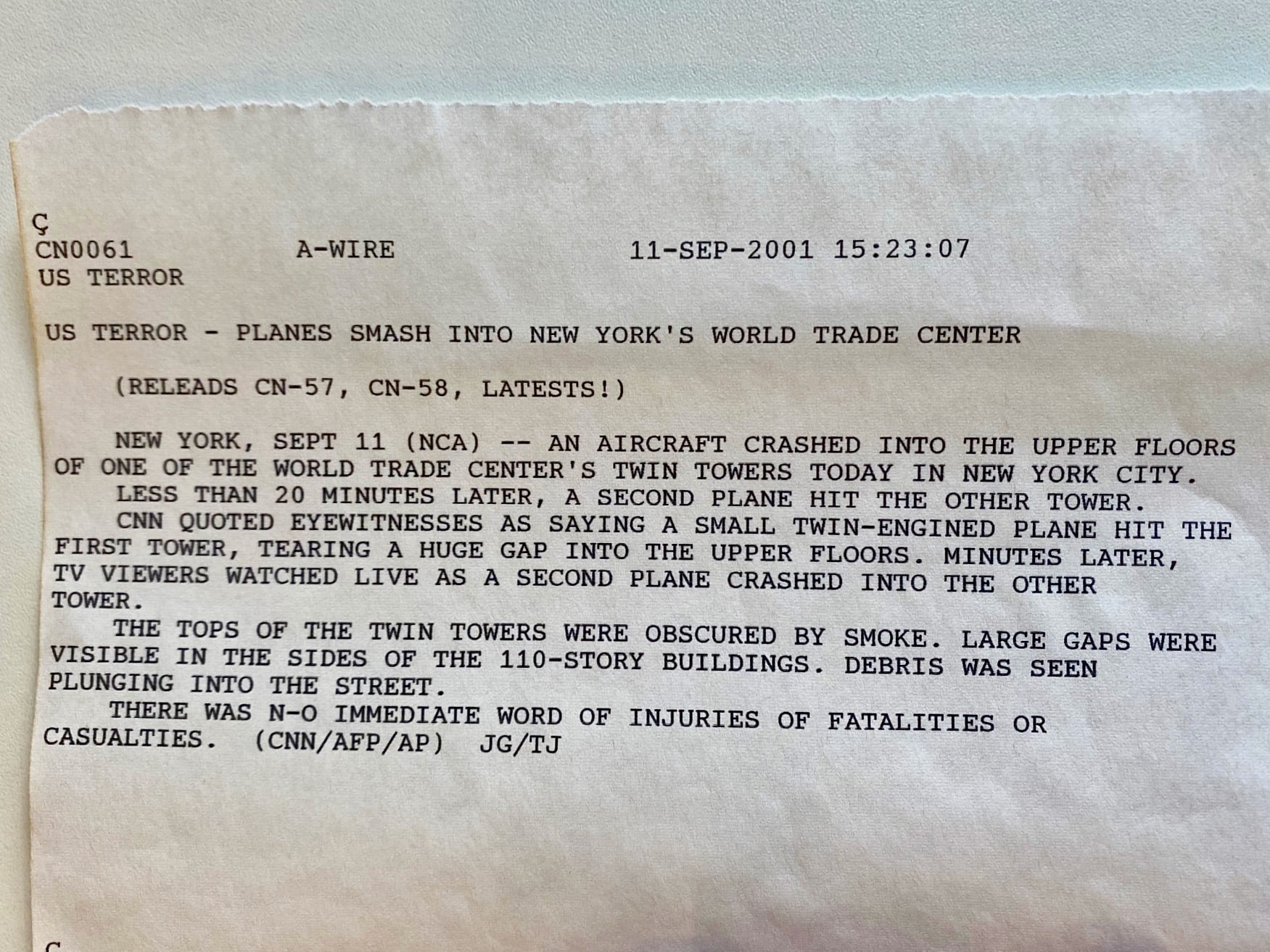

Certainly, the tone of both RFE and RL, especially in the early days, was strongly anti-communist, but what many people don’t realize are the lengths to which the stations went to vet information before it was broadcast (particularly after the 1956 Hungarian uprising, when the radio was rightly taken to task for aggressively -- and tragically -- promoting the anti-Soviet rebellion). As I wrote in the intro, my first job at RFE/RL was as a news-writer. I was responsible for ripping and reading news feeds from major wires like Associated Press, Reuters and AFP as they spilled out onto the newsroom floor through a long bank of printers. One of the first rules I learned was that every news item we prepared needed to be verified by two independent news sources before it could go out over the air.

After I was promoted to deputy managing editor and interacted daily with RFE/RL’s upper management (in both Prague and Washington), I can’t recall ever once being told by a high-level radio exec to report on a story in a particular way – or to give favorable coverage to a certain person, story or country. On the contrary, we would have perceived any kind of intrusion like that as highly unusual and unwelcome. We were left largely on our own to compile our own news and feature reports.

Looking back, I wonder how much editorial control would have even been possible, given the anarchic nature of a sprawling organization like RFE/RL. During the time I was there, de facto editorial control of the station fell to the 20 or so individual country directors, who were in charge of putting together the daily broadcasts in more than 30 different languages. Even if it had been the desired goal, it would have been very difficult to impose and enforce any kind of subjective editorial line.

I joined RFE/RL in 1997, long after the move to Prague was complete. Sadly, I never experienced life at the station during it's Cold-War heyday in Munich, though I heard plenty of war stories over the years from older staff members who made the move to Prague.

The station's first Prague headquarters -- before relocating in 2009 to a new purpose-built facility outside the center -- was situated in Czechoslovakia's former Federal Assembly at the top of central Wenceslas Square. After Czechoslovakia split into separate countries, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, in 1993, the building no longer served any useful purpose. The structure itself, an unwieldy Brutalist pile from the 1960s by the Czech architect Karel Prager, wasn't exactly suited to an international radio station, but RFE/RL did its best to make it work.

During my time at the radio, RFE/RL functioned like a miniature United Nations in the heart of Prague, though I doubt many residents at the time realized quite the degree of cultural and linguistic diversity housed in their former Federal Assembly. Each day, colonies of Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Ukrainians, Tatars and Chechens would rub elbows at editorial meetings and over cafeteria lunches with bunches of Russians, Lithuanians, Armenians, Serbs, Bulgarians, Georgians and many others. Later, the list of nationalities would grow to include Iranians, Iraqis and Afghans.

The English-language newsroom, where I spent most of my time, occupied an enormous, expansive atrium-like space on the building's fourth floor. English functioned as the radio's working language, though none of our individual country services broadcast in English. Our newsroom was responsible for compiling news reports and writing feature stories that the broadcast services would then translate and use on their own air waves.

The radio was managed by a mix of political appointees from Washington and radio lifers who all had their offices arrayed on the building's all-important second floor. The appointees would come and go, depending on which political party was in control back home. Naturally, we had the occasional culture clash -- both between management and staff and among the various broadcast services, but relations, on the whole, were surprisingly civil and free of partisanship. Everyone from the president on down seemed bound together by the collective mission of providing objective, unbiased reports in the service of supporting democracy and human rights.

When I first joined the radio, I found the learning curve to be pretty steep. My first order of business was to familiarize myself with all of our broadcast countries, including the newly independent, former Soviet republics in the Caucasus and Central Asia -- as well as the various idiosyncrasies of their respective despots. While all the autocrats were broadly similar in the ways they amassed their fortunes and repressed their citizens, they all faced different opposition groups and rivals as well as specific economic and political problems that had to be learned.

Our “favorite” ruler back then was probably Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov, an autocrat so unhinged he once officially renamed all of the months and days of the week on the Turkmen calendar (just because he could). He renamed January as “Türkmenbaşy,” his adopted nickname, meaning “leader of the Turkmen people.” He called April “Gurbansoltan,” the name of his mother.

Then there were the bewildering names and details of all of the newly frozen, separatist conflicts waged in the 1990s in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse. There was the Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan that killed tens of thousands of people and was later mediated by the OSCE’s Minsk Group. Around the same time, wars in South Ossetia and Transdniester pitted separatist groups against, respectively, the Georgian and Moldovan governments. One of the bloodiest conflicts, of course, matched Russia against separatists within its own borders, in Chechnya. That war set the stage for the entry of Vladimir Putin.

Russia, under Boris Yeltsin, had lost the first of the two wars the country fought against the Chechens in the '90s and 2000s – a fact that contributed to his downfall and opened the door to Putin. Putin succeeded in leveraging Russians’ grievances and fears over the defeat. In Part 2, I’ll share stories about Russia from my own time at the radio that show Putin’s been operating from the same playbook, more or less, ever since.

(Click here to go to Part 2)