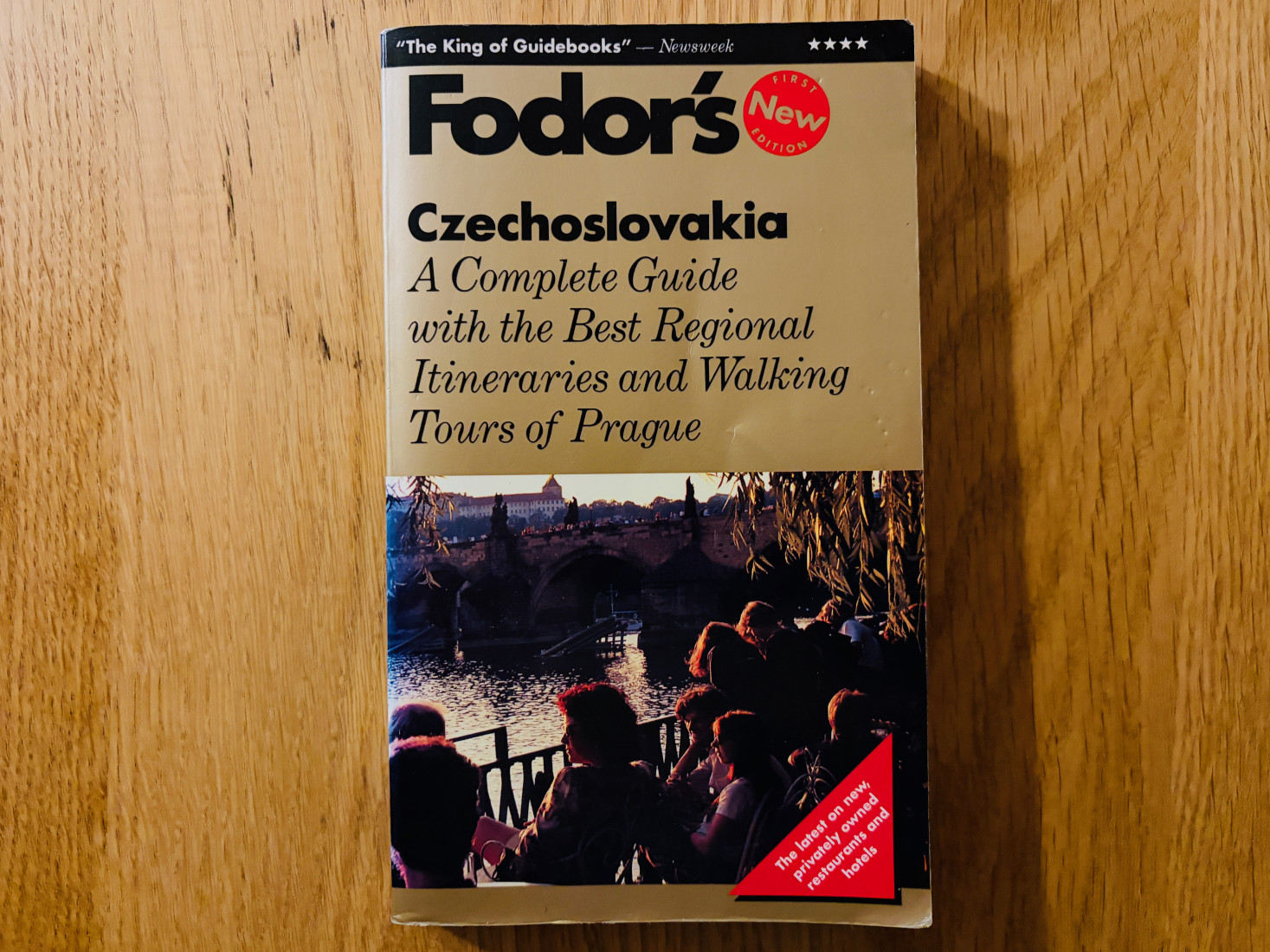

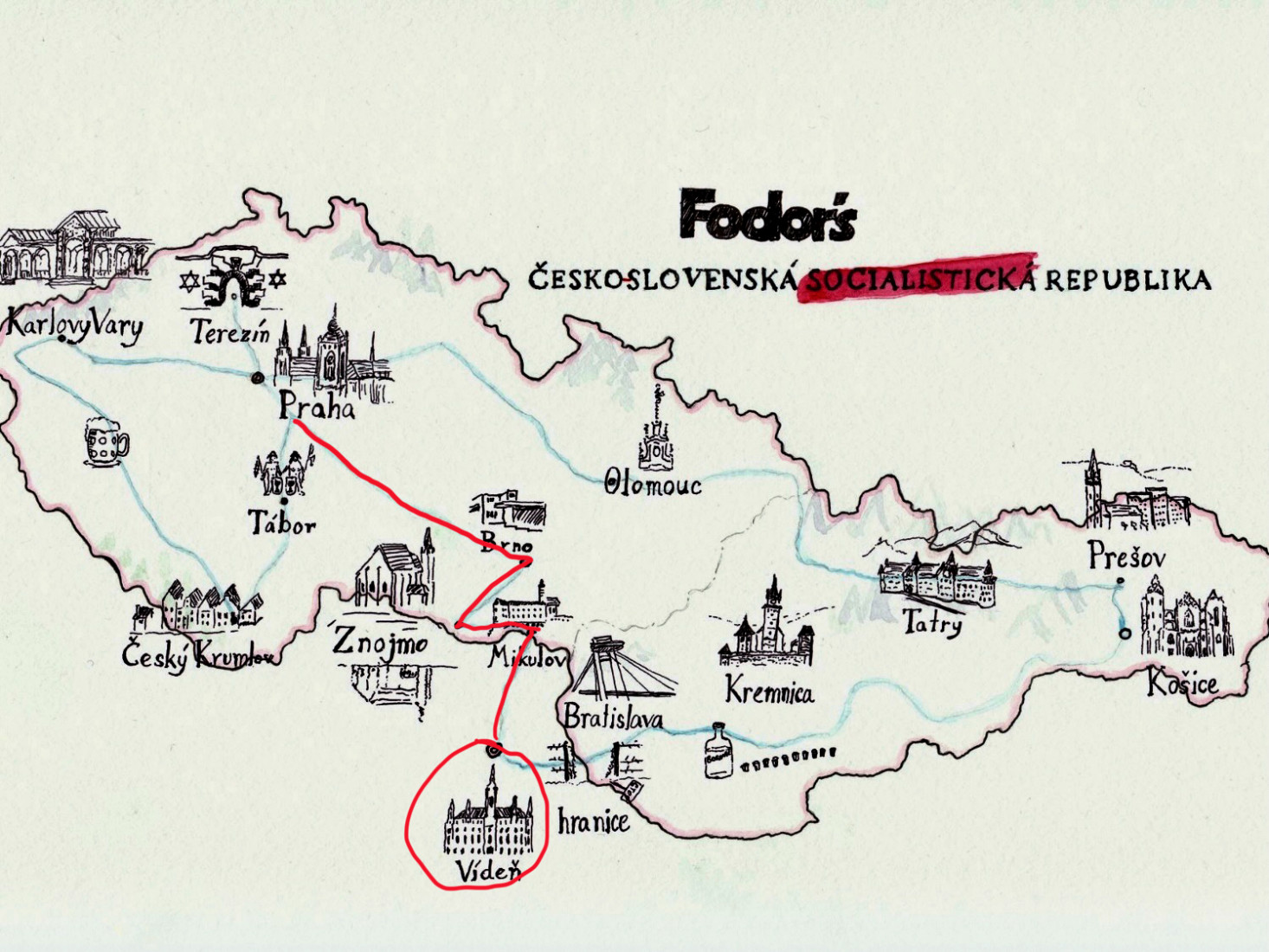

As our approach to Czechoslovakia would begin from Vienna, we naturally started our trip in the Czech province of Moravia, just a couple of hours due north of the Austrian capital.

Generally speaking, there isn’t a lot geographic variation along the border between Czechoslovakia (now Czechia) and Austria. The border runs for nearly 500km (300 miles), and for long stretches you have the feeling that both sides of the line are essentially the same place. The border only starts to mark out what feels like a genuine division toward its northeastern end, where Austria and Moravia butt up against each other. It’s here that the flat grasslands of the Austrian province of Lower Austria (Niederösterreich) run into the first faint foothills of the Carpathian mountains. Austria’s green fields give way suddenly to the subdued earthen pinks and yellows of Moravia.

We crossed into Czechoslovakia at the cold and lonely border checkpoint near the town of Mikulov and caught our first glance at the country we would spend the next month traveling around. Indeed, the town's landmark castle, where Napoleon once stayed in 1809 and visible for miles around, marked a dramatic start to the journey.

These days, I really enjoy Mikulov, which is known both for its wine tourism and Jewish heritage. I even brought my parents here on a family visit in 2017. On this first early trip with Delia, the town’s tumbled-down buildings dazzled in the cold afternoon sunshine, but the main square was eerily quiet. Many of the tired-looking storefronts still bore generic, communist-era names like “Shoes” and “Groceries.” Clearly, not much of the commercial energy unleashed by the Velvet Revolution had yet reached the Moravian borderlands. We weren't entirely sure anyone here even knew about it yet.

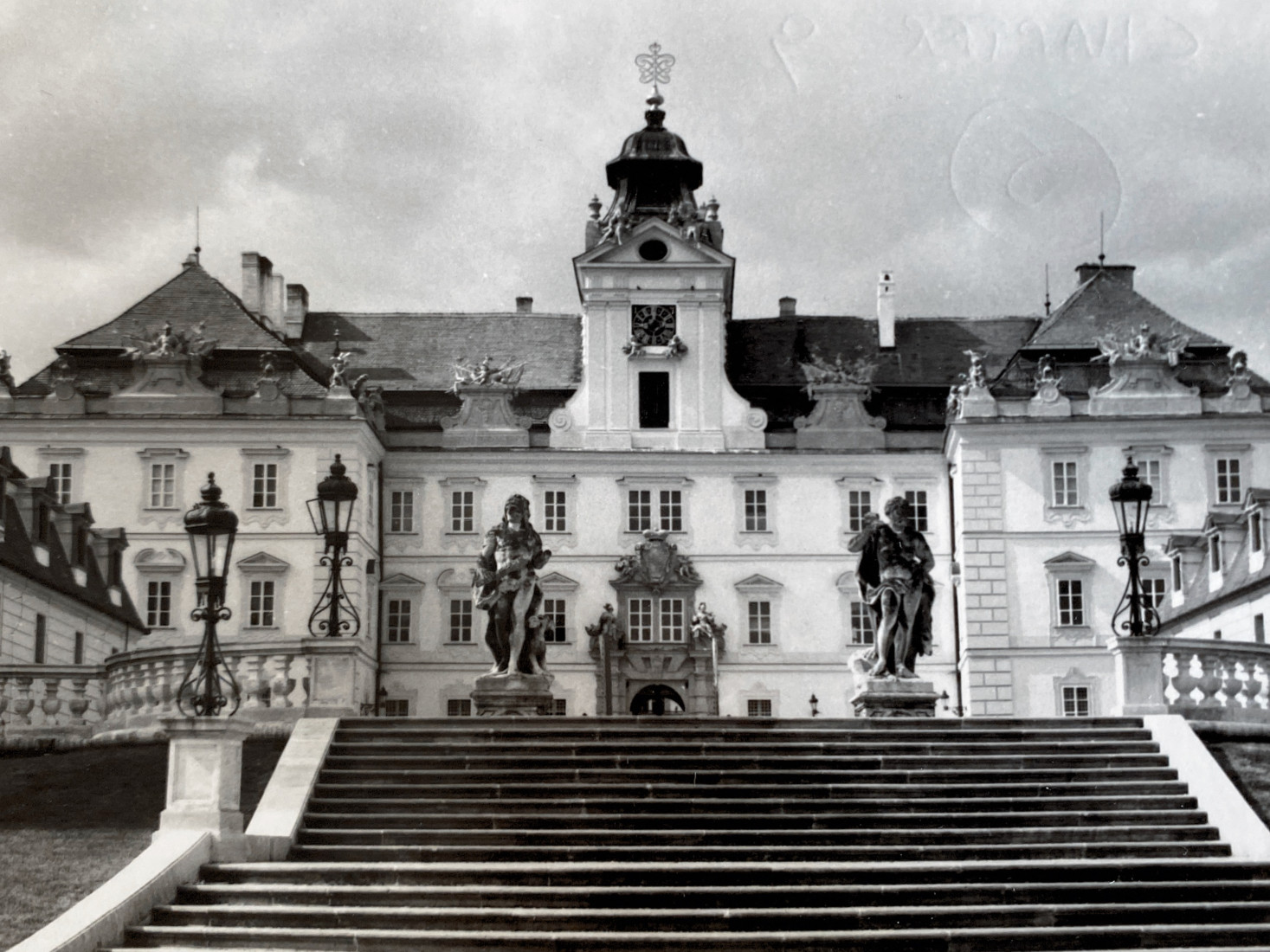

In the nearby town of Lednice, the sheer scale of the grand, neo-Gothic chateau there, once owned by the noble Liechtenstein family and now a UNESCO World Heritage site, was breathtaking but was also badly neglected and marred by chipped bricks and peeling paint. The windows of the palace greenhouse, at the back, had been reduced to broken shards. We marveled at the palace's garden minaret -- not a religious site per se, but rather a folly, a 19th-century decorative in-joke of the kind popular among the late-stage Habsburg nobility.

We tried our best to follow our own advice and look beyond this superficial decay. We found enjoyment, instead, in trying to spot the surviving remnants of these historic borderlands, which for centuries had marked out the turf between the crown lands of the Margraviate of Moravia and the Archduchy of Lower Austria. The region had once been lorded over by the wealthiest families of the Habsburg Empire and still boasted the impressive old piles to show for it.

'Zwischen Österreich und Mähren'

Later that first day, just after dusk, we stumbled onto the aptly named “Border Chateau” (Hraniční zámek) at the village of Hlohovec and noticed some ice-skaters out on the castle’s frozen lake. We had remembered to pack our own skates and were soon out there gliding along with everyone else. The two of us sprinted out to the middle of the lake and turned around to take a fuller look at the castle behind us. That’s when we first noticed the dramatic writing that for at least a century had been etched onto the building’s flood-lit exterior: “Zwischen Österreich und Mähren” (Between Austria and Moravia).

Those words appeared to us in that moment like an omen. These two places had never been meant to be separated by barbed wire. That first night we put in at another grand chateau, this one in the town of Valtice. The building, just another magnificent Liechtenstein-family residence, was arguably in even worse shape than its sister chateau at Lednice but had the advantage of a shabby hotel -- the "Hubertus" -- burrowed into one of its wings. We toasted our arrival that night in our room over a glass of local wine.

We poked around southern Moravia on the second day and made our way over to the nearby border town of Znojmo. As in Mikulov, we again tried to ignore the neglect and notice instead the town’s underlying prettiness: sweeping squares, a towering town hall and beautiful vistas out over the Thaya River at the back. As we roamed Znojmo’s deserted streets, we searched in vain for a decent place to eat or stay. These days, Znojmo has several pleasant hotels (though still not many good restaurants).

We finally found a room outside the center at the “Dukla Hotel,” a communist-era high-rise with the same sketchy disco scene I knew well from my previous business trips around the country as a journalist. We avoided the dance floor that night and opted instead to celebrate Delia’s 30th birthday over another bottle of wine back in the room. Oddly our wine that night – which we had purchased on the spot at the hotel’s reception desk – was not actually from Moravia at all. Instead, unwittingly, we had bought a bottle of "Ludmila" wine from the town of Mělník, north of Prague, in faraway Bohemia. We admired the bottle’s unique, squat shape that looked exactly like a jug of moonshine.

The 'Manchester of Moravia'

We spent a couple more days roaming around southern Moravia, including a stopover in the pretty, medieval town of Telč, whose immense main square dwarfed the modest town itself, and then set our sights on Moravia’s capital city, Brno. After having lived in Brno for a month in 1988 to study Czech language, I knew the city fairly well. Delia had also been there before, but both of us wrestled with the question (as we would in several places around Czechoslovakia) of why travelers would ever want to come here in the first place?

This was years before Brno cleaned up its streets, opened up some new museums and showcased its stunning heritage of interwar, modern architecture, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s landmark “Vila Tugendhat” (the Tugendhat at the time was used to house guests of the city of Brno and closed to the public). Once tourists had seen Brno’s historic and quirky Gothic town hall, paid their respects to the pioneer of modern genetics, Gregor Mendel, who lived and worked here, and climbed to the top of grim Spielberg (Špilberk) Castle, there wasn’t much else to do. In the end, we presented Brno as a living museum of 18th-and 19th-century industrialization – the “Manchester of Moravia” – and invited readers to take in the surviving examples of Empire and neoclassical architecture.

Before leaving, however, Delia and I happened to stumble onto a particularly macabre sight that we knew would leave a much deeper impression on readers than the city’s neoclassical architecture. We had little idea of what was lurking beneath Brno’s Capuchin Monastery as we descended into the monastery's cellar on our last morning in town to take a quick look around. The Czech town of Kutná Hora, these days, gets a lot of attention for hosting a creepy church made entirely of human bones, but for pure spookiness, it’s hard to beat the rows of 18th-century “mummies” – the preserved remains of the town’s former noblemen – splayed out on the dusty floor of the Capuchin Monastery’s crypt. A ghoulish warning, scribbled on the wall, still haunts me to this day: "As you are now, we once were; as we are now, you shall be.”

Back on the Road

From Brno, Delia and I slid along the icy D1 highway all the way up to Prague. The road – fiendishly narrow in stretches and paved partly in grooved slabs of raw concrete – was every bit as harrowing then as it is today (it’s still the site of many unnecessary road fatalities each year). The only advantage in 1991 was that traffic was lighter and moved more slowly. We counted very few high-powered Audis and BMWs on the road, and those old communist-era Škoda cars topped out somewhere around 100km per hour (60 mph), and often slower. I drove extra carefully on that stretch. I had no intention of joining those hapless noblemen laid out back in Brno any time soon.

As Prague would be the focal point of the book, we planned a stay of around a week. We didn’t have the budget for a nice hotel (even back then pretty pricey), so instead we located a private room at a newly opened pension near central Wenceslas Square. A youngish couple greeted us at the door and showed us to our modest quarters in what turned out to be the kids' bedroom of their own apartment. The couple’s son, an energetic guy of around 10 years old, was especially keen to show us his impressive collection of international beer cans. His prized possession turned out to be a can of American-made "Budweiser." I didn’t have the heart to tell him the beer wasn’t actually very good ...

Click here to continue reading Part 3.

*Rough Guides also published a travel guide on Czechoslovakia around the same time.

Did you like the story and want to add your own experiences? Or maybe help me to correct something I didn’t get right? Write me at bakermark@fastmail.fm.