The best thing about researching a guidebook (or even using a guidebook while you travel) is that, sure, it takes you to places you think you want to go to, but it also takes you to places you’ve scarcely heard of and never had any idea you wanted to see -- until you get there.

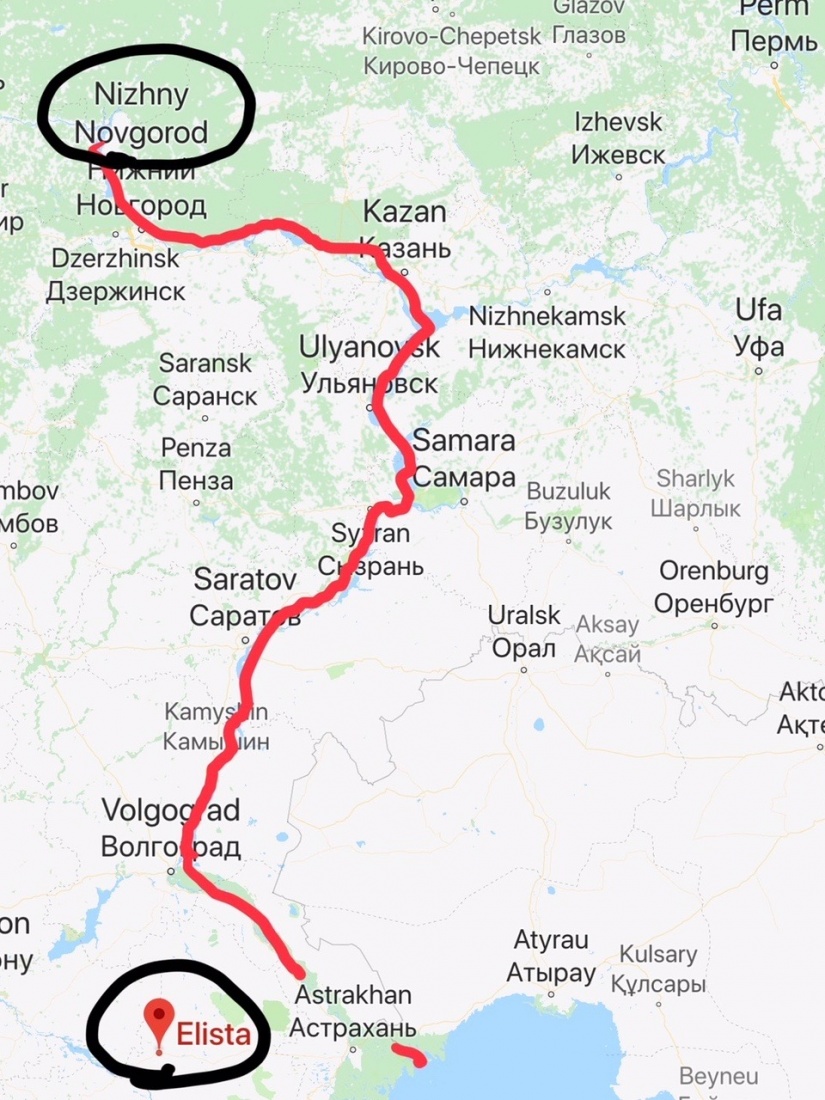

That describes a big part of that Lonely Planet Russia assignment for me last year. On that trip, I wouldn’t be going to Moscow or St Petersburg (except to change planes), but rather exploring the country’s Volga River basin – a vast length of land that runs down the center of European Russia from Nizhny Novgorod in the north all the way to Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea (I’ve marked out the route on a photo here).

As I scanned Lonely Planet’s existing Russia chapter, I recognized a few cities along the route. I’d pass through the Tatar capital, Kazan, which I was familiar with from working at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. I’d also be visiting big cities like Samara, Volgograd, and Nizhny that I knew at least something about. The smaller places along the way, though, like Ulyanovsk and Saratov, elicited only faint echoes of familiarity.

When I got to the city of "Elista," toward the end of the chapter, I confess I drew a total blank. It was described as the capital of the Republic of Kalmykia (a Buddhist republic, to boot). I’d never heard of it, and Buddhism, seriously? Shouldn’t this place be in a different region of the book, further to the east?

As generations of guidebook writers (and guidebook users) before me have realized, though, the places you never knew you wanted to see often turn out to be those places you don't easily forget. As so it was with Elista and Kalmykia.

As I was making my way down the Volga, hopping night trains from city to city, I quickly realized there was no easy connection for reaching inland Elista. Eventually, I figured the best bet would be to take a minibus (marshrutka) over from Volgograd – about five hours. Elista is also approachable by minibus from Astrakhan in about the same amount of time.

In terms of hotels, I lucked out. Before leaving Volgograd, I had googled around a bit and booked a room at the Hotel Ostrovok, which turned out to be one of the finds of the trip. It was tiny (just four rooms in what looked to be a large family house) but spotlessly clean, with a firm bed and reliable hot water. The woman who greeted me at the door couldn’t speak much English (so we made do with my comical Czech-inflected Russian). She handed me a small, mimeographed map of the city that included a short list of places nearby to eat and drink. Once I dropped my bags and washed off some of the minibus from my body, I hit the streets of Elista.

While each of the cities I’d visited so far along the trip had their impressive buildings and pretty spots, there was nothing to prepare me for the bizarre spectacle of the towering red Pagoda of the Seven Days, standing at Elista's central intersection of Pushkin and Lenin boulevards. There was something undeniably refreshing seeing such a colorful, chaotic structure amid the bland, rectilinear facades of the Soviet-era buildings around the square. A sidewalk leads from here through a procession of playful Buddhist-inspired archways, temples, and follies to a park called the Alley of Heroes. Dozens of Buddhist- and pagan-inspired sculptures were added to the streets and sidewalks in the 1990s. This YouTube video shows their quality and diversity.

I wandered for hours through the park and around town, taking in the various temples and sculptures. I realized early on, though, that this was probably as good as it gets in Elista. It’s a small city (just around 100,000 people) and there's not much for visitors to do – but I was smitten.

The two most important sights are both located outside of the center. The Golden Abode of Buddha Shakyamuni is a relatively new temple (from 2005), with a decorative prayer hall and a 35-ft (11m) tall statue of the Buddha. There’s a small museum on the history of Kalmyk Buddhism.

Chess City, about 2 miles (4 kms) from the center, reflects former Kalmyk president and multimillionaire Kirsan Ilyumzhinov's mania for the game of chess. This "city" -- composed of a modern gaming hall and some Olympic-style bungalows -- evolved from his dream to transform Elista into a global chess capital. The idea never caught on, and the area now feels somewhat forgotten.

Ilyumzhinov is as colorful a character as are the pagodas that line Elista's streets. In addition to being Kalmykia's president, he's served as president of the World Chess Federation, FIDE, since the mid-1990s (though his term in office has been riddled by controversy). Ilyumzhinov was also famously abducted by aliens (in 1997) and spoke about that experience on this YouTube video.

So how did a Mongol tribe of Buddhists make it this far west?

The Kalmyks -- descendants of a western-Mongolian tribe called the Oirats -- migrated here to the banks of the Volga about 500 years ago, bringing their culture and religion with them. For centuries, they served the bidding of the tsars well, defending the southern border of an expanding Russian empire from Ottoman and other incursion. Indeed, the Kalmyk Khanate of the 17th century was especially known for its fierce fighting ability.

During the 20th century, under Stalin, the Kalmyks met with a similar tragic fate as did many other non-Russian ethnic groups in the Soviet Union. They were formally accused of siding with Nazi Germany during World War II (though, in fact, many Kalmyks opposed the Nazis in the war and fought alongside the Russians).

During the night of December 28, 1943, the Kalmyks were rounded up and forced into unheated railroad cars for deportation to Siberia. Many thousands died along the way. Following Stalin’s death, in the mid-1950s, then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev allowed the Kalmyks to return to their Volga homeland, though in fact less than half the prewar population of around 100,000 made the trip. These days, Kalmykia's population numbers around 300,000, with about 40% of people claiming adherence to Tibetan Buddhism.

In the decades after the war, the Kalmyk republic was subjected to all manner of failed Soviet land-management schemes, and much of the territory – even that which I could see from my minibus window -- remains blighted and unusable. These days, you have the feeling of a city and people hanging on by a thread. You don’t see much outright poverty in Elista, though there’s little of that new-money gloss that catches the eye in places like Samara or Volgograd.

Okay, so this is where this post goes off the rails.

I enjoyed my time in Elista and learned a lot, though to be honest, I didn’t fall in love with the food. You might want to file this part of the story under “So You Want To Be a Guidebook Writer?”

I’m generally an adventurous eater, and as a travel writer, of course, we’re encouraged to sample local cooking wherever we go. And so it was on my first evening in Elista. I was pretty hungry after that minibus ride and walking around town, and ready to try some Kalmyk dishes. There aren’t many restaurants in Elista, and the restaurants that do exist don’t really specialize in local cooking. I suppose it makes sense. When people spend money to eat out, they want something different from what they can make at home.

Our Lonely Planet guidebook suggested the “Gurman” restaurant, located in a nondescript shopping center next to a bowling alley, as the best mid-range place in town for Kalmyk food – and I have no doubt that’s likely true. The problem was that on the night of my visit – a quiet weekday evening – there was not a soul in the place. I walked into the massive dining room a bit hesitatingly, wondering if the restaurant was even open. I was quickly surrounded by probably all of the waiters on duty that night and escorted to a table. Though I didn't have a good feeling from the empty room, there was no backing out.

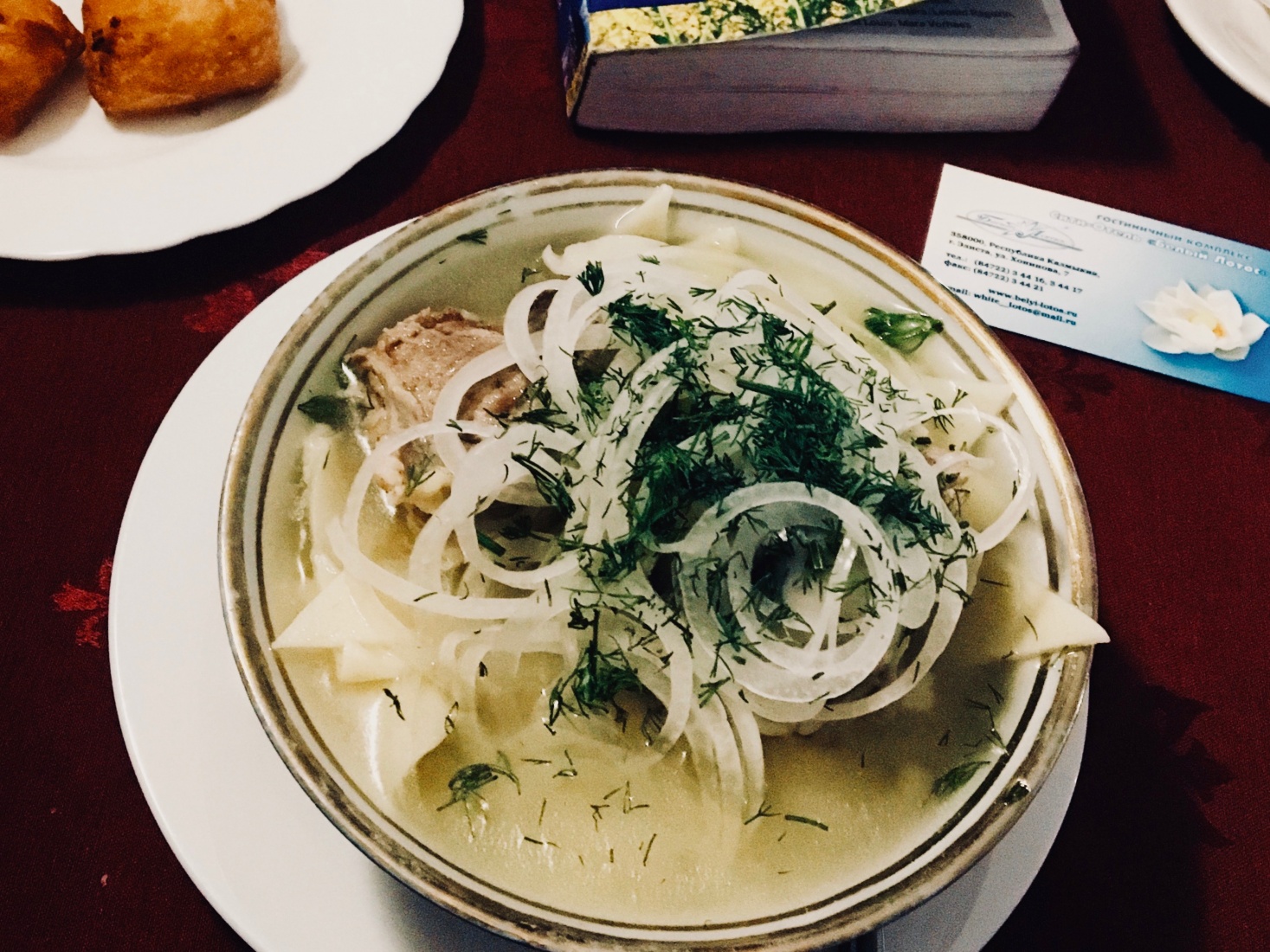

I mumbled that I was interested in trying some Kalmyk food, and the floodgates opened. Before I knew it, I had a huge cup of Kalmyk tea (dzhomba) in front of me, followed by balls of dough fried in oil (bortsg), and then a heaping plate of hasn makhn, which (news to me) turned out to be slices of boiled mutton-muscle, served on pasta and covered in onion. The side for this was some kind of sheep-intestine soup – maybe dotur? No matter how much I politely protested to the waiters that I really couldn’t eat any more, the dishes just kept flying out of the kitchen.

I knew I was in trouble after my first sip of dzhomba, which tasted exactly like a cup of warm, salty butter. I read later that the Kalmyks, as a nomadic tribe, developed their cuisine to maximize calorie intake and not so much for the flavor (I'm pretty sure they succeeded on the calorie front). As I tucked into the mutton, I bit hard into what was probably a ball of one of the animal’s joints (at least that's what I hope) that had been hiding under the pasta. Spit or swallow? My gag reflex went into overdrive.

And so it continued -- my first Kalmyk meal under the watchful, hopeful gaze of four or five waiters hovering over my table and eagerly awaiting a bite-by-bite appraisal. I ate what I could, signaled thumbs up, and asked for my bill.

I did better on subsequent meals in town, but some nights on the road, that's how it goes.

Read more about my adventures along the Volga in the newly updated Lonely Planet Russia guide. I wrote about the amazing city of Volgograd in an earlier post here.

For more on Kalmykia and other places on the Volga, check out episode #605 of the Amateur Traveler podcast: "Travel Along the Volga River."

Pingback: Travel Along the Volga River in Russia (Podcast)