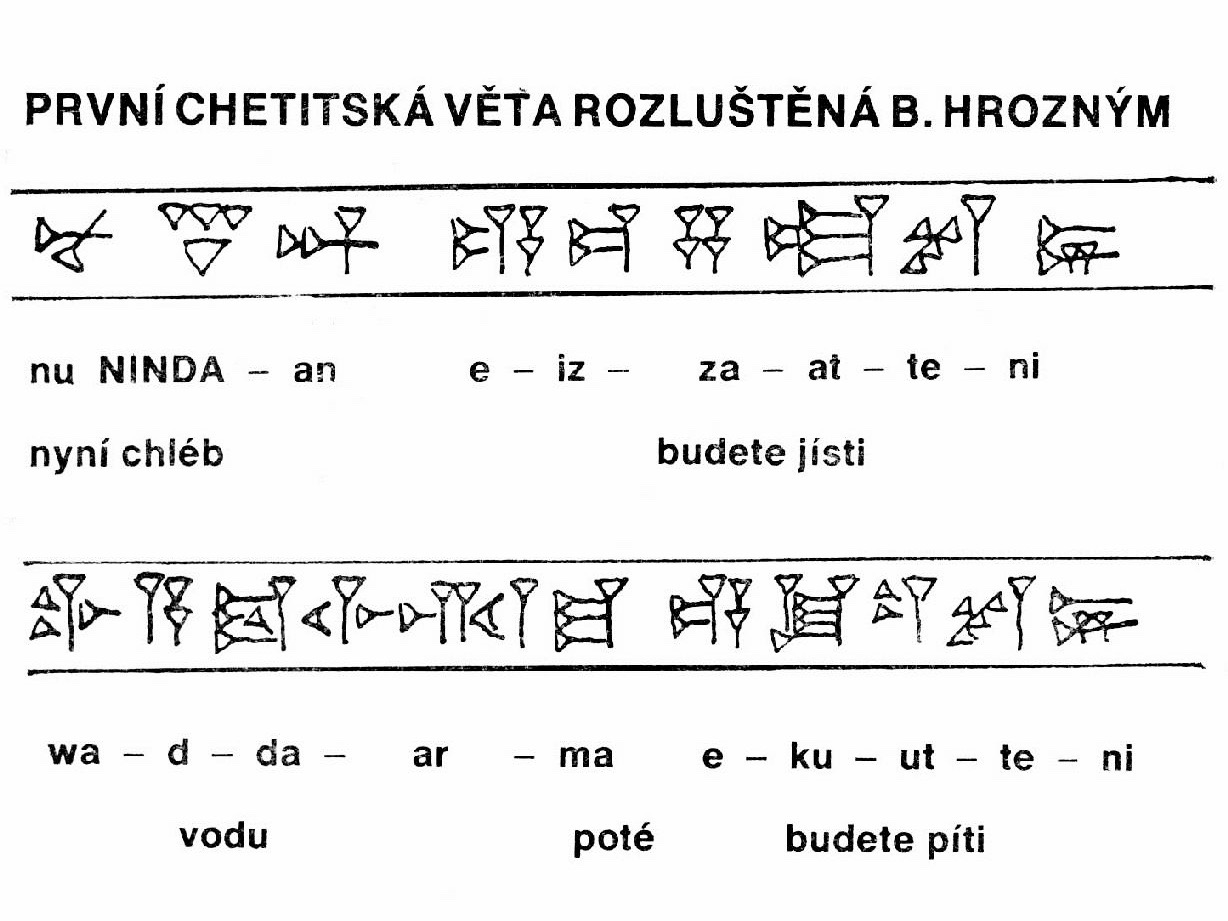

“Now we will eat bread and drink water.”

By deciphering this simple sentence, practically the most banal thing one can write (and the title of this blog post in Hittite), the early-20th century Czech linguist Bedřich Hrozný helped to crack one of the most vexing riddles facing archeologists and orientalists of his day: how to read the pictograms etched on thousands of clay tablets stretching back more than 3,000 years that had been found in central Turkey.

The chance discovery of the cache of tablets, by French and German archeologists in the late-19th century, stunned the world and proved beyond doubt the existence of an obscure tribe -- the Hittites -- that until then had only been known from a few scant references in the Bible. Hrozný’s insights would flesh out this empire and show us how powerful and developed they really were.

I don’t want to get ahead of the story, though. I would never have learned anything about the Hittites or Hrozný if it weren’t for an invitation I received a few years back from an old friend and fellow journalist, Colin Campbell, who had recently retired from journalism and was working on a novel set in Turkey. Colin asked if I might have some free time to accompany him around the country to help get a better feel for the place and collect details for his book.

I had just left my own editing job at Radio Free Europe in Prague and had some free time on my hands. I happily accepted and we arranged to meet on a chilly late-autumn day in Istanbul. From there, we would embark on a road trip all around Turkey with nothing more on the agenda than to ride around and take the pulse of the place. One of the riddles Colin needed to solve for his book was to see how long it would take us to drive from the Turkish capital, Ankara, to Izmir (or something like that). The answer: longer than you think.

We had fun on our days in Istanbul and, later, traveling around central Anatolia and Ankara (I've posted a few photos of Istanbul and Ankara below). All the time in the car gave us plenty of opportunities to chat and catch up. Colin is one of those guys you might call a polymath, with an interest in a wide -- and eclectic -- range of topics. These included, among other things, Turkish military coups (useful when riding around Turkey) and "Rebetiko," a soulful style of Ottoman-influenced Greek music. For the purposes of this article, as it happens, he also knows reams about archeology and antiquity.

One of the places Colin especially wanted to visit was the small city of Boğazkale, about 120 miles (200 km) east of Ankara. While Boğazkale, itself, was nothing special, it was close to Hattuša (Hattusha), the ancient capital of the old Hittite empire. It was a place he’d always wanted to see.

I must have seemed dumbfounded at the time. Like everyone else, I simply assumed the Hittites were just another tiny, long-disappeared (or perhaps never-existed) tribe that pops up in the Bible or in church readings of some kind or another. I had never given them a second thought.

Our trip to Hattuša, though, opened up my eyes to a phenomenally advanced civilization for its day, and to a tale of linguistic cryptography worthy of an Alan Turing type story (and maybe even Benedict Cumberbatch treatment).

So, what was Hrozný’s act of genius in cracking the code of the clay tablets?

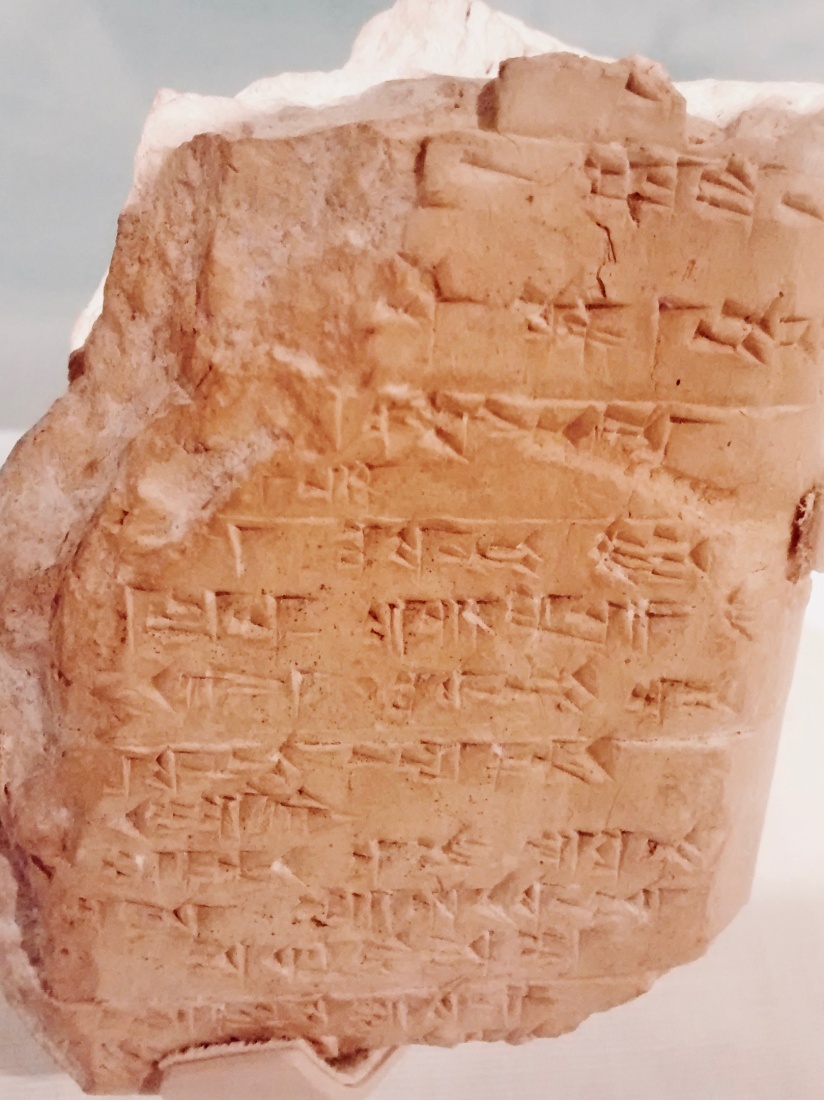

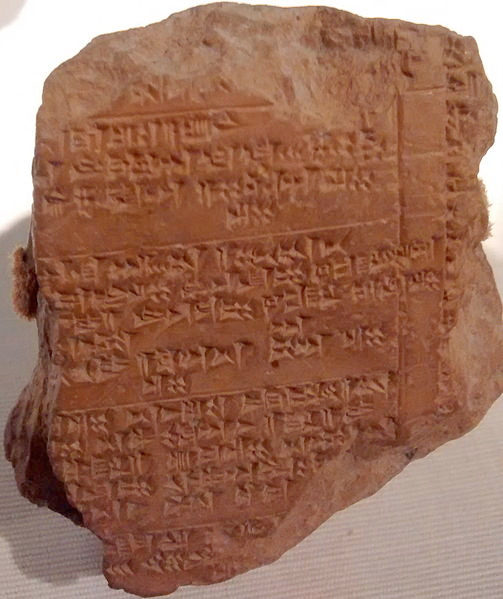

I’m no expert in linguistics, but the way I understood it was like this: the Hittite tablets were etched in standard cuneiform writing – in other words, in the symbols originally developed by ancient Sumerians and used by other civilizations across Mesopotamia. The language itself, however, was unique (and unintelligible). Cuneiform is a kind of hybrid “alphabet” in that some symbols denote actual objects – such as “king” or “bread” – that are common across civilizations, while other symbols are used to stand in for words or syllables of words that form part of a distinct language.

The principle is not unlike modern emoji or texting language. For example, if you send someone a text on your phone that says “U 2?” (as shorthand for “you too?”), you’re using a kind of pictogram. The “U” and the “2” are symbols that are recognizable across many languages, but the words they represent, “you” and “too” in this case, are unique to English. Once linguists succeeded in separating out which pictograms were actual things and which were merely symbols or syllables of words, they were still left with the challenging task of deciphering the language.

As linguists and orientalists poured over the Hittite tablets in the early-20th century, they naturally assumed that whatever language the Hittites used, it must have belonged to the Semitic family -- the same group that includes Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic. It only made sense given the location of Hattuša and what was believed to be the geography of the Hittite empire. That initial assumption, though, yielded little in the way of understanding.

This is where Hrozný steps in. As a conscript in the Austrian army in World War I, he apparently had hours and hours to contemplate the Hittite tablets. One day as he was considering a tablet etched in symbols that corresponded to the words “nu ninda-an ezzateni watar-ma ekuteni,” he had his eureka! moment: Hittite wasn’t a Semitic language at all, but rather an early form of Indo-European language – the same linguistic family that includes English, German, Czech and many other modern European languages.

Hrozný worked this out in the following way. He recognized the symbol “ninda” as the Babylonian (and common) sign for “bread.” If a sentence had the word bread in it, he reasoned, it might also contain the word “water” – and the word “watar” in the phrase looked very similar to the German word “wasser.” Might “ezzateni” mean “eat”? After all, it looks a little bit like the German word for eating, “essen.”

He was also struck by the apparent declination of the words (the way word endings changed depending on where a word stood in a sentence). This is a characteristic feature of Indo-European languages. From here, he worked out his famous translation:

"Now we will eat bread and drink water."

It was just a matter of time before the language was cracked. Hrozný published the first Hittite grammar book in 1917. Today, we can read Hittite, a language developed more than 3,200 years ago, as easily as we can read French or German -- or even Czech (which says something!).

When looking back at mankind’s great political achievements, we often exhibit a recency bias. The American Constitution (1787), the Magna Carta (1215), the high point of the Roman Empire (around 100 CE), and even the rise of Athenian democracy (5th century BCE) all came centuries after the Hittites.

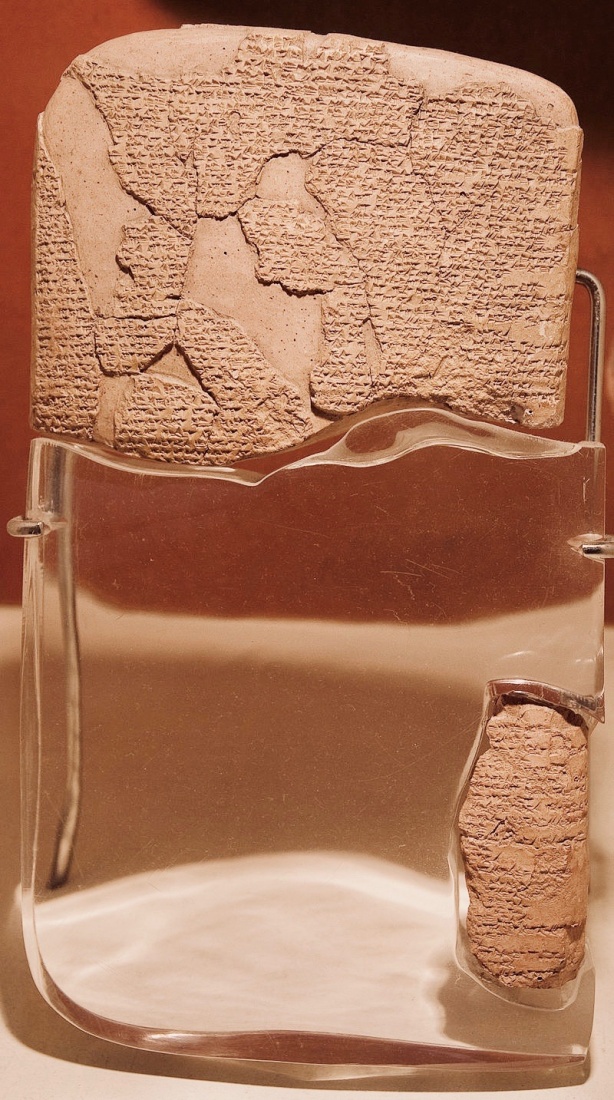

The clay tablets revealed a highly developed civilization, with an intricate legal code and surprisingly sophisticated social interactions. From personal letters etched on the tablets, we’ve learned much about Hittite commerce, health, love affairs, marriage, and even divorce. It was a thoroughly modern society.

Colin and I ended up spending a couple of days in and around Boğazkale, rambling through the ruins of Hattuša and visiting other old archeological digs nearby. They're still carrying out research in the area and trying to answer some basic questions, including why the Hittites chose such a remote and unforgiving landscape for their capital city.

The Hittites’ greatest historical moment, arguably, came in the epic “Battle of Kadesh,” which pitted thousands of Hittite charioteers against the mighty Egyptians, led by Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE). The battle, in modern-day Syria, took place in or around 1274 BCE and ended, by all accounts, in a draw. The Treaty of Kadesh, negotiated 15 years later, ended the fighting and is considered the first treaty of its kind between squabbling empires. Originals of the treaty have been discovered in both Egypt and Hattuša (in 1906), and a copy is on display at the United Nations in New York.

The last mystery concerning the Hittites, that unfortunately the tablets can’t tell us much about, is what ultimately happened to them. Not long after the Treaty of Kadesh, around the year 1200 BCE, the Hittites, along with many other developed civilizations in the region, simply vanished in what many historians call the “Bronze Age Collapse.”

Whether it was due to the rise of a mysterious group of conquerors, the "Sea Peoples?", or some other cause that brought the Hittite empire down, we may never know. The area around Hattuša was resettled sporadically in the centuries following the collapse, but no lasting civilization ever again took root there. The area remained largely uninhabited until French and German archeologists started digging in the 19th century.

Radio Prague produced a very good radio piece on Hrozný and the Hittites in 2009. Listen to it here.

Not long after this post went live, I received the comment below from a Czech reader via Facebook who pointed out some other linguistic connections (in this case, to Czech) that I didn’t see:

“You point out the connection to Babylonian and German… I wonder if ‘ekuteni’ has anything to do with the Czech ‘tekutý’ (ed note: the modern Czech word for ‘liquid’).

I responded by saying I think the point here was that Hittite and languages like German (and Czech) have a common Indo-European root, so that a handful of words for basic things like water may indeed look similar. Only once Hrozny made that insight, could the translation of Hittite really begin.

He responded:

“Right, it’s a good insight. It clicked for me as soon as I saw the translated phrase. ‘Ninda’ looks like ‘naan’ to me, and ‘watar’ is rather obvious … But as a native Czech speaker, sounding out ‘ekuteni (and given ‘watar’ as context) immediately made me think ‘tekutý.’ Just thought I’d share. I think it’s fascinating the cognates we find in what initially appear to be such distinct languages. For example the Czech ‘léka?’ and the Icelandic ‘lækjur.’ My father and I hypothesize an ancient root in Celtic :)”

I was happy to see on Twitter that the Department of Indo-European Studies (and the Proto-Indo-European Lexicon) at the University of Helsinki had seen the Hittite article and retweeted it and posted it to their Facebook page. Jouna Pyysaloto, at the Lexicon, wrote me the following:

“You’re in a good company @markbakerprague: If interested in Anatolian languages, please follow this link, it’s an etymological dictionary of (Indo-European) languages, initially built up on Hittite, Luwian and Palaic – the rest of the etymology to be added: http://pielexicon.hum.helsinki.fi”

He also joked around a bit about not eating Hittite food — to which I replied that there must have been some good recipes carved on some of those clay tablets. His answer:

“Yes, there certainly were, but we do not recommend to try all of them: ‘UGULA LÚMEŠ MU?ALDIM ma-a-aš-ša-a[n d]a-a-i’ means ‘the chief of cooks takes a maša.’ Maša also appears in a name (Hitt. maš·?uilua- = Sum.. PÍŠ.TUR) meaning ‘small mouse.’ Don’t try that (one) perhaps …”

The similarities between Hittite and modern European languages continue to come in. If “maš” is Hittite for “mouse,” Hrozny might have easily recognized it, as the Czech word for mouse is “myš” — not that far at all from “maš”!

Mark, Great great piece! Really fascinating. Your comment about recency bias struck a chord – I really believe that people are incapable of putting history in context and realizing how brilliant man has always been. The article and the references to water and tekuty made me think about how languages transform over time what I learned is the origin of the word Vltava – the beautiful river running through Prague. I read that it is a melding of old germanic words “wild ahwa” (wild water). Keep up the good work. Tony

Thanks to Jouna Pyysaloto, of the Proto-Indo-European Lexicon at the University of Helsinki, who retweeted my article, this blog post attracted the attention of Hittite scholars around the world, including in Turkey.

Sevgul Cilingir, a Research Assistant at Ege University, Izmir, one of those scholars, saw the post and later wrote to make some minor corrections to my (or, rather, Hrozny’s) Hittite translation, and I thank her for writing (see below):

“Dear Mr. Baker I just wanted to add a comment to your post. You translated NINDA-an ezzatteni watarma ekutteni as “we eat bread and drink water” the correct translation is “you eat bread but drink water” NINDA is Sumerian word for bread -an is Hittite accusative suffix ezzatteni is the conjugation of the verb “ed-” that means eat. Watar is in Hittite and -ma is the enclitic word that means “but”. ekutteni is conjugated in the same way as “ed-“. Thanks again for your interest to Hittite language. It always attract my attention the success of Hrozny to decipher Hittite language while the World War I took place in those days. All the best from Turkey, Sevgul”

The main critique of Hrozny is that his deciphering was based on a lucky guess, rather than any rigorous analysis of the text. When he tried to repeat this with the Minoan Linear B script, he failed utterly. The people who finally deciphered Linear B also made a leap of insight (that its language was an early form of Greek) but that came after years and years of intensive analysis. Hrozny, unfortunately, had a hard time acknowledging he was simply lucky to have been right, which is why his reputation as a scholar today is somewhat diminished.

Hi Matt, thanks for your input. I was wondering why Hrozny’s name isn’t celebrated everywhere 🙂

Hello!

I read your interesting article on your Web site about the first sentence deciphered from the Hittite language. Do you know any location where I can get this first sentence in text form, or how I can convert the image you have in your article with OCR into UTF-8 or UTF-16?

Best regards!

Thank you for reading and leaving a comment. I am not sure what you are looking for exactly, but perhaps you will find more information on Hrozny’s Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bed%C5%99ich_Hrozn%C3%BD

I wish you good luck!

Mark