I can’t remember my first visit to Slovakia’s High Tatras, but I do remember the first time I ever laid eyes on this narrow range of giant peaks I was charmed. I guess that must have been February 1991, when I was working on my first-ever guidebook project, one that my girlfriend at the time, Delia, had managed to snag in the travel-writing euphoria that erupted after the fall of communism in 1989.

The breach of the Iron Curtain had opened up Central and Eastern Europe to western tourists, and the American travel publisher Fodor’s was eager to plant its flag on the newly liberated ground. Through friends of friends, a New York-based editor at Fodor’s, Chris Billy, had contacted Delia sometime in 1990 to ask if she might be interested in resurrecting their moribund “Fodor’s Czechoslovakia” title, which had been out of print for many years.

Delia and I were both living in Vienna at the time, so the project would be manageable from the travel perspective. She enthusiastically said yes, and I went along for the ride. In February 1991, we rented a car and drove the length and breadth of Czechoslovakia—back then a rather long country—during the coldest winter I’ve ever spent in this country.

We ended up driving from Cheb in the far west of Czechoslovakia all the way to Košice in the east, and everywhere in between, but when we eventually rolled up to the snow-buried High Tatras, and our room in the haunted-looking, fin-de-siècle, Alpine-baroque Grandhotel Praha (see photo), we knew we’d found something special. The hotel’s worn interiors, frayed carpets and chipped plasterwork—the effects of years of communist-era neglect—couldn’t hide the illustrious ballrooms, balustrades and chandeliers (channelling my best Patrick Leigh Fermor here). From that point on, I’ve only ever been able to see the High Tatras through a pair of sepia-toned, Wes-Anderson-Grand-Budapest-Hotel-style goggles.

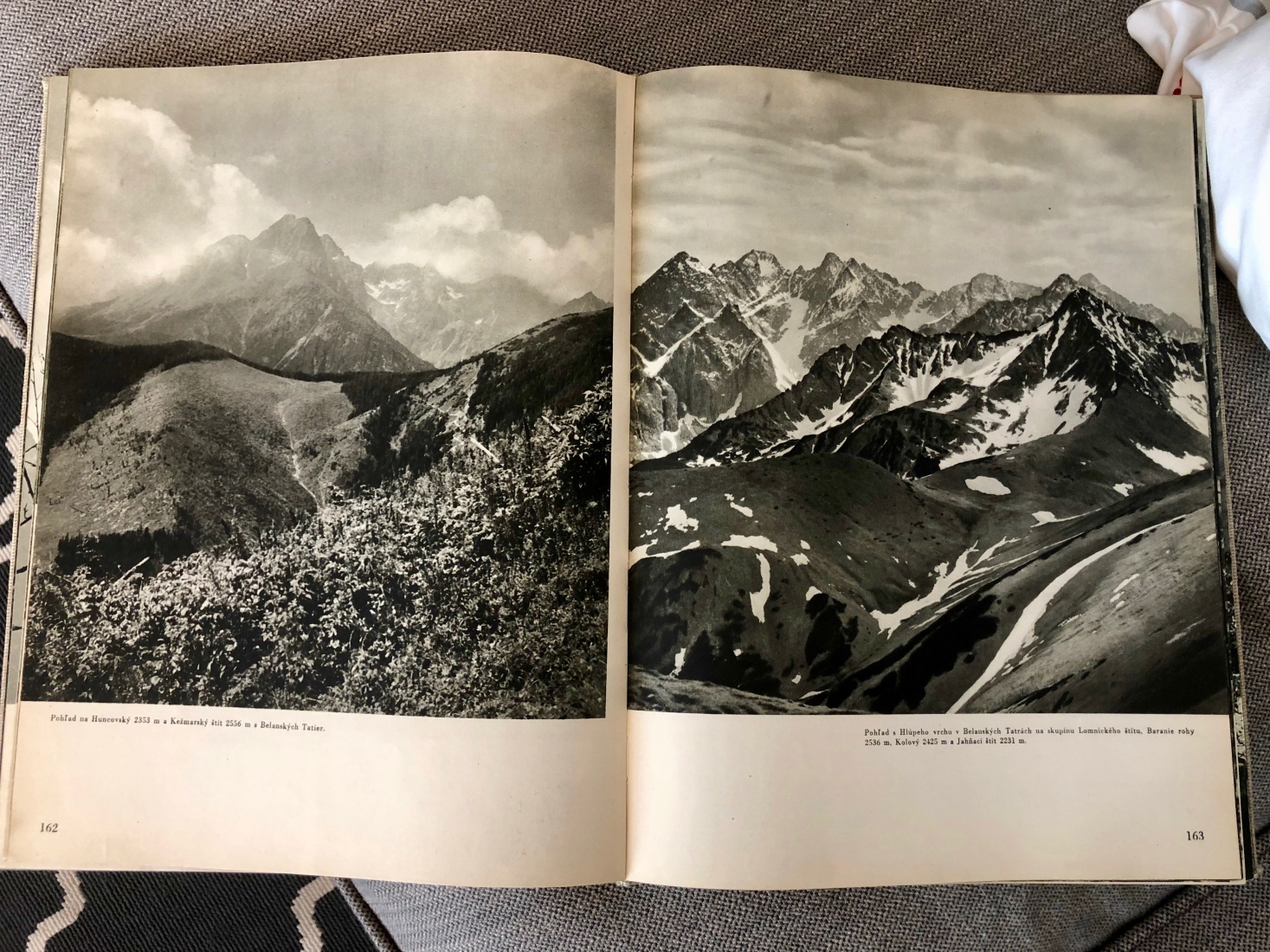

For readers who might not be familiar with the High Tatras, the mountains are located in northeastern Slovakia, near the western end of the enormous Carpathian range that sweeps eastward for some 1,500 kms (930 miles) through Ukraine and Romania. The High Tatras mark out Slovakia’s northern border with Poland and can be approached from either side of the frontier (in summer, you can hike across the peaks from country to country).

The High Tatras are a relatively small group, running only about 50 kms (30 miles) from end to end, though the peaks here are the highest of the entire Carpathian chain. The tallest mountain, Slovakia’s Gerlachovský štít, rises to a height of 2,655 meters (8,711 ft). Indeed, one of the most appealing aspects of the High Tatras is how they appear to burst straight out of an ordinary field to reach such an altitude, all from such a relatively small plot of ground.

On the Slovak side, three small resorts cluster along the peaks’ southern face. The oldest resort, Starý Smokovec (see map, below), sits at the center. It’s flanked to the west by Štrbské Pleso, with its pretty Alpine lake, and to the east by Tatranská Lomnica, home to the Grandhotel Praha. The three resorts, and several smaller hamlets in between, are connected by the unique, narrow gauge Tatra Electric Railway, which makes it easy to move from place to place.

All three resorts and the railway were built up in the 19th and early-20th centuries, when the High Tatras were part of Hungary and the greater Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the decades well before the advent of mass tourism, summering in the mountains enjoyed a lengthy vogue among the Empire’s well-to-do, and the opulent hotels were designed to cater to demanding tastes.

During the communist period (1948-89), those lavish High Tatra hotels -- with their hard-to-hide bourgeois origins -- suffered greatly but managed to survive. Those old moneyed classes, by then, were long gone, and Czechoslovakia’s communist regime -- like governments throughout the Soviet-occupied Eastern bloc -- attempted to transform these formerly upper-class resorts into more worker-friendly, mass-market places to recuperate.

Alongside the older, more-luxurious hotels, which were generally starved of investment, the communists added dozens of drab, utilitarian-looking hotels, dormitories and sanatoriums to accommodate the crowds. And that’s pretty much the way things stood when Delia and I rode into town in February 1991.

I returned to the High Tatras several times in the early '90s, after moving from Vienna to Prague and starting a new job as an editor with a fledging English-language newspaper, “The Prague Post.” In 1992, I traveled at least twice to the mountains with my friend, Jenny (I’ve posted a couple pictures here below). As I remember, she was not an especially enthusiastic hiker back then. We’d cheat a little by riding a funicular up the mountain and then walking out along the pretty “Magistrale” trail that skirts the peaks at an elevation of about 1,300m. I wrote up an account of one of those trips for The Prague Post’s travel section, which they published in December 1992 under the title: “No Neon, Just Mountains” (which I’ve borrowed for the title of this post as well).

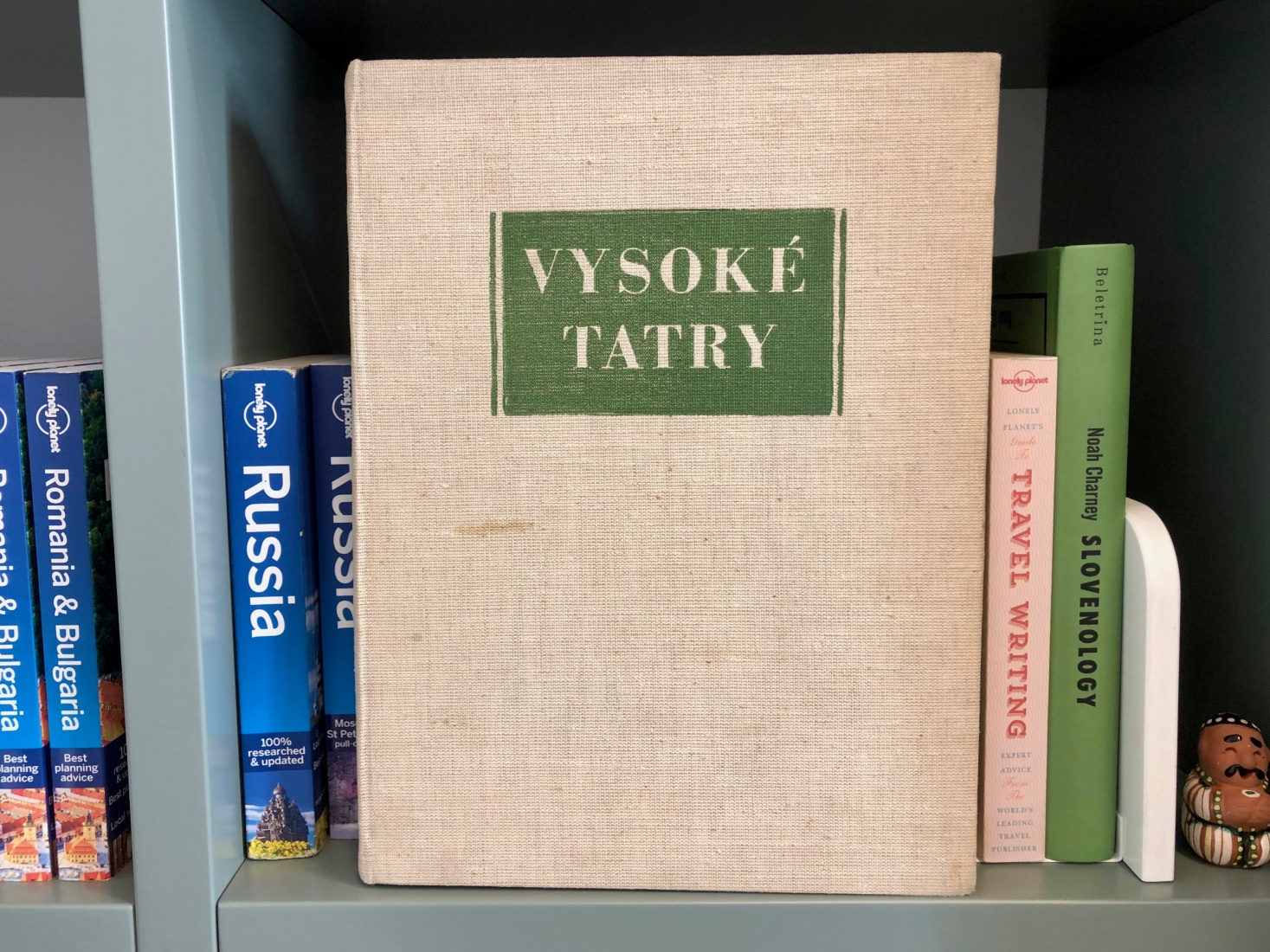

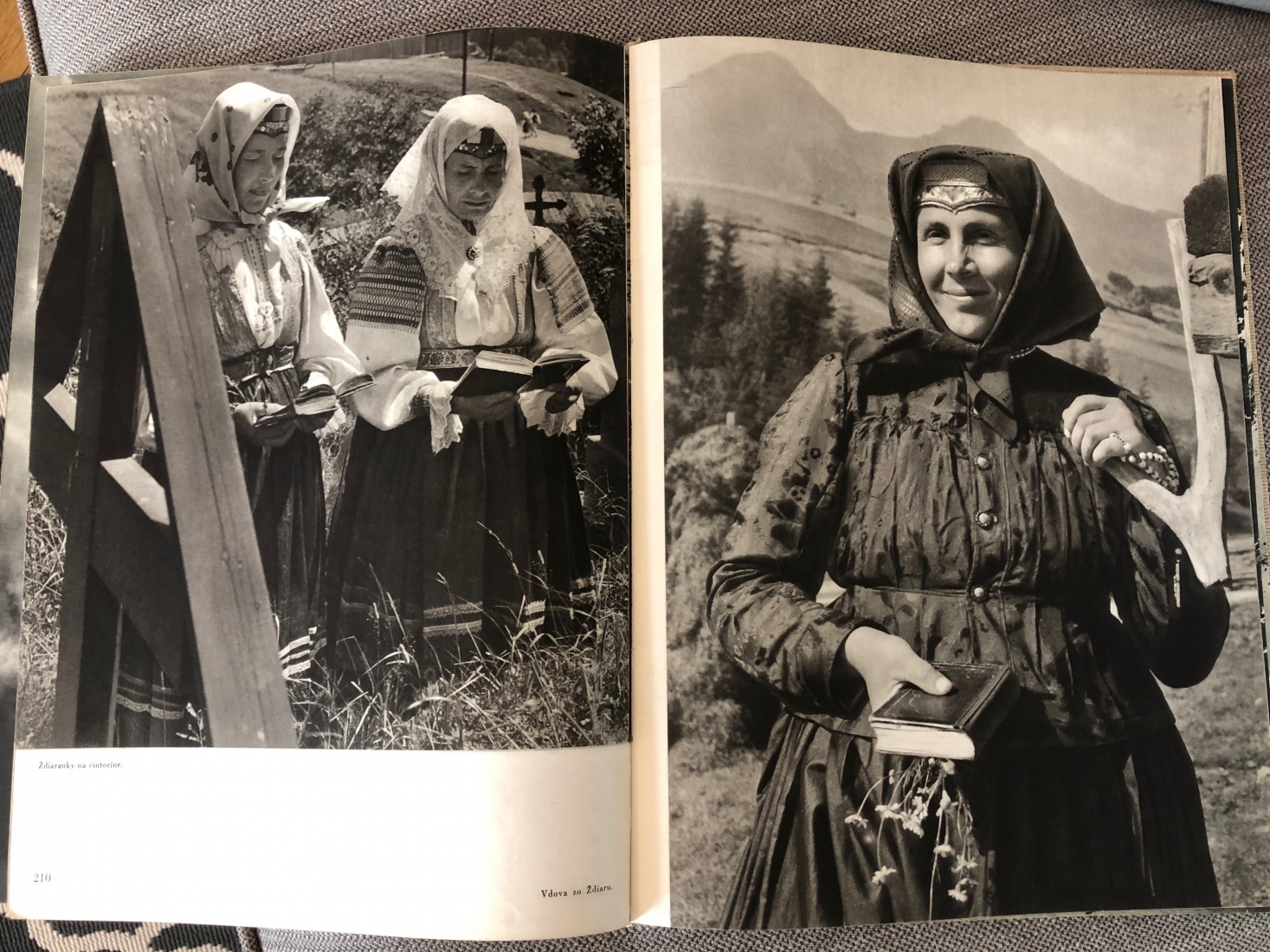

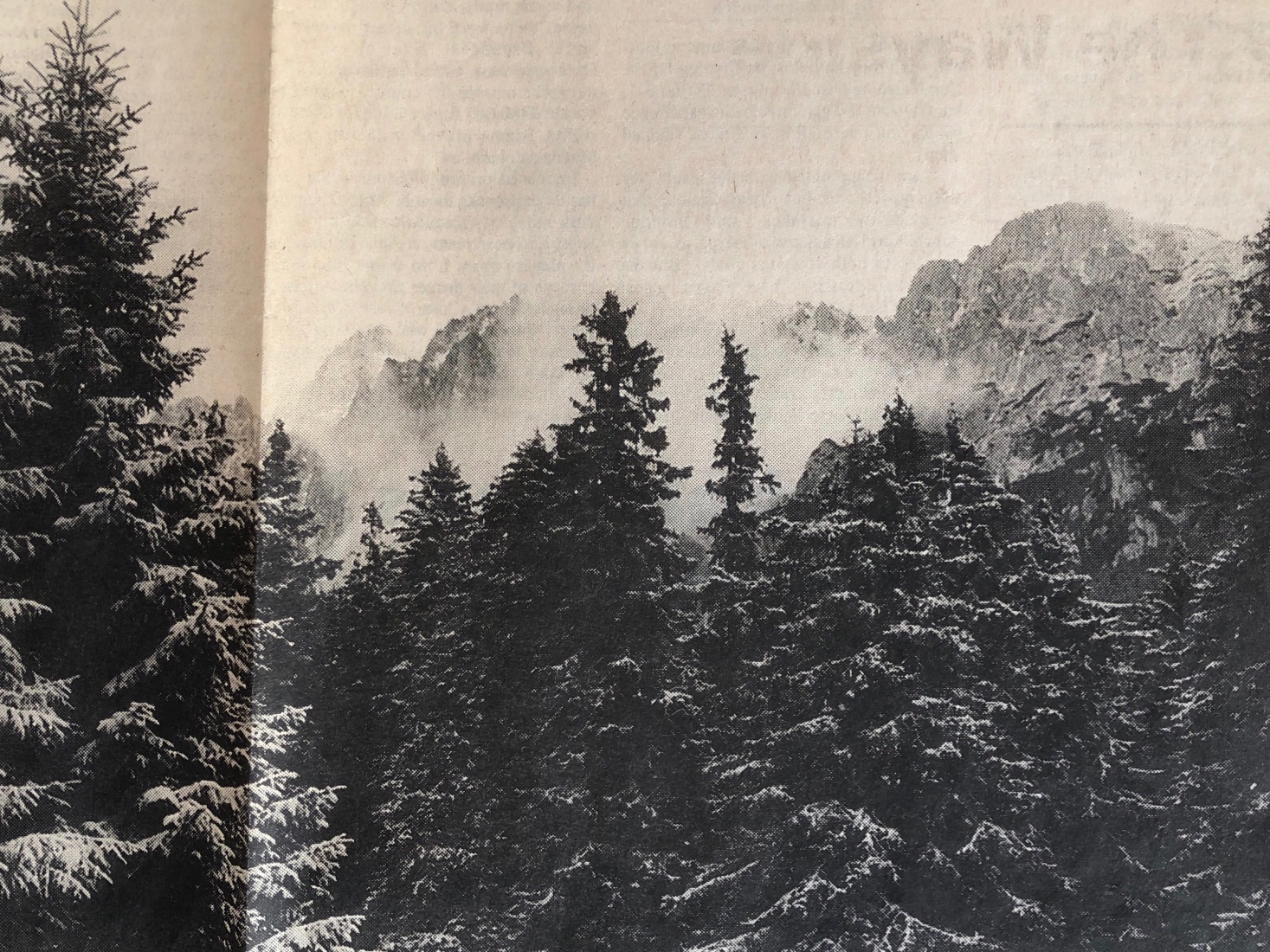

As I tried to conjure up some of the early emotions I associated so strongly with the Tatras, I paged through a musty, old picture book from 1951, “Vysoké Tatry” (“High Tatras”), that Jenny gave me as a gift in 1992. As I looked through the dramatic black-and-white shots of lonely peaks, lakes and mountain flowers -- glossed over with a sheen of communist propaganda in the form of images of smiling peasants and newly built hotels -- I felt some of the old excitement and apprehension of those first, early days for me in Czechoslovakia. I’d just embarked on what felt like a totally new beginning (in a country that was getting a fresh start as well).

I still remember one of the saddest aspects of the break-up of Czechoslovakia in 1993 was the realization the split would put the High Tatras on the other side of a new Czech-Slovak national border.

I have lots of stories from the mountains, but one in particular stands out. For several years running, in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, I would travel to the High Tatras to celebrate my birthday, which falls in July. I’d drive or fly, and then book a room in one of those big, old, mansion-like hotels (by that time, I’d switched over almost entirely to the Grandhotel Starý Smokovec).

I can’t remember now why I felt it was so important to celebrate my birthday there, but it did mark a nice break from the hot summer in Prague and was a relatively easy place to escape for some down time and fresh air. Normally, I’d spend the daytime hours on the trails and then treat myself to something nice to eat back at the hotel, and attempt to find some nightlife in the evening.

Those birthdays all run together in my mind, but a trip I took in 1998 or ’99 made a special impression. For that journey, I decided to fly on Czechoslovak Airlines (ČSA) from Prague to the eastern Slovak city of Košice and then take an airline shuttle bus over to the Tatras, about 100 kms (6o miles) away. After checking in at the Grandhotel Starý Smokovec, I ate dinner at the hotel and walked over to a small dance club nearby to have a beer and listen to some music.

It was a smallish crowd, but everyone seemed to be in a good mood and it was easy to meet people. Not long after I got there, I met a young couple from Bratislava. He was a Slovak engineer (maybe “Petr”?) and she was from Mongolia (I don’t think I ever managed to pronounce her name correctly). Once I told them it was my birthday, the night went totally off the rails. They treated me to beer after beer after beer, and I ended up staggering out of there sometime in the wee hours.

As I attempted to make my way back to the room, I found a piece of grass in front of the hotel to stretch out on and contemplate the stars (birthdays do that to you). I ultimately passed out, and all those beers ended up setting off a comical chain reaction that would last for weeks after I finally made it back to Prague.

I actually overslept in the grass, missed my breakfast, and more importantly missed the shuttle bus back to the Košice airport and possibly my flight home. That put me at the mercy of the local taxi mafia, and I vaguely recall my severely hung-over brain trying to haggle in advance over the fare in a mix of English, Czech and very poor Slovak. We finally settled on a price of around $100 for the hour-long trip and raced away to try to make the flight.

We made good time to Košice, and I even had a couple of minutes before boarding the plane to drink a cup of badly needed coffee at the airport bar. I took one sip of the coffee, though, and spit it out all over the counter. It was the worst coffee I’d ever had in my life, a fact I promptly told the shocked waitress. She eyed me coldly and said there was nothing wrong with it. “It’s just normal coffee.” She turned out to be right.

What I didn’t realize was that at some point in the night, whether it was from over-drinking, sleeping in the wrong position or something else, I had completely knocked out my sense of smell. It was a case of (thankfully) temporary "anosmia" that I only confirmed once I got back to my apartment in Prague and made a cup of my own coffee. It too tasted exactly like overly ripe pipe tobacco. For the next month, everything I would eat or drink tasted just like Borkum Riff. (I had no idea at the time that within a decade or two half the planet would know all about anosmia thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic).

Nothing so memorable happened on this last stopover in August of this year (2019). I no longer celebrate my birthdays in clubs and I prefer sleeping in a bed to passing out on the grass. But the mountains did look great and it was nice to reconnect, if only for a couple of days, with a place that had once made such a strong impression.

(Scroll past the map for more photos).

I enjoyed reading your birthday story. The photos of the mountains and the architecture are evocative. The whole post gave me a sense of this place so far away. Thank you. I found your blog from a mention on the Cold War Conversations site.

Hi Lou, Thank you so much for reading and leaving a comment. Very happy you liked the story! Mark

Excellent descriptions and photos. Thank you.

Hi Mark

I enjoyed this article. I just finished a family tree project and some of our ancestors are from this region. Thanks for all the descriptions and celebrate wisely!!