First, the good news from my end. Aside from a few minor health scares -- like breaking out into a cold sweat for no reason or having a cough or scratchy throat (spring allergies?) -- I feel good and healthy. I’ve limited contact with others to a minimum and try to keep my apartment as virus-free as possible. I’ve taken steps to protect my mental health too. My situation is as good as it can be under the circumstances -- and much better than many people on the front lines -- and for that I’m grateful.

I can’t say, though, there haven't been a few of those “blood-runs-cold” moments. One came a few days into self-isolation. I’d been joking with friends about how our lives had become remakes of the movie “Groundhog Day,” where Bill Murray gets caught in a time warp and every day becomes a repeat of the day before. One morning, I woke up with the thought that our collective movie isn’t Groundhog Day, but rather ‘The Boy in the Plastic Bubble,” a schlocky film from the '70s in which John Travolta plays a guy with an immune deficiency and he can’t leave his bubble without risk of dying. I wasn't Travolta, but my apartment had definitely become my bubble.

It dawned on me it might be several weeks, or even months, before I'll have an actual face-to-face conversation with another person. I’ve been on long, solo research trips before, and I know I can tough this one out. The key is to take it day-by-day. That bubble thing, though, freaked me out (and still does).

The other blood-runs-cold moments mostly have to do with family back in the U.S., where the virus is spreading quickly. My impression is that the Czech Republic has done a better job than the U.S. in slowing the spread of the virus, first closing down all non-essential shops and businesses on March 12 and then gradually introducing tighter restrictions (including the mandatory wearing of face masks in public).

The numbers are scary here in Prague, around 3,800 confirmed cases as of early April and rising, but there’s a growing feeling of hope the containment measures will eventually work. I don’t always share that optimism when I look at the U.S. and read the terrifying accounts coming out of New York City and other places (though I try to stay encouraged by the fact there are many knowledgeable people around the world working to stop the virus).

I won’t go into the contents of those darkest moments. I can’t let my mind go there, and I’m sure all of us are haunted by the same demons. I do think, though, that my fellow expats, separated from their loved ones by many miles as well as ever-tighter travel restrictions, have it especially rough these days.

Self-care is particularly important, and one of the first steps I took during the lockdown was to limit my exposure to Facebook and Twitter. Social media can be a great way to stay connected and it’s an important part of my work as a writer, but at times like these, it can also serve as a panic trigger and dangerous source of misinformation.

My main problem with social media, and it predates coronavirus, is that we users have only limited control over what we see in our newsfeeds. Sites like Facebook and Twitter function much in the same way as our own brains, and the various posts and tweets we see are like random thoughts. Some posts are benign or bring pleasure, but many play on our darkest fears. Like our own thoughts, the posts and tweets often lack context and are not necessarily true or accurate, yet our minds and bodies react as if they are.

Under normal circumstances, I can handle the randomness and occasional darkness, but as the pandemic began to take hold, I started to find my social media feeds to be more triggering than entertaining (or helpful). That's when I realized it was time to (temporarily) check out.

I still maintain a backdoor access to both Facebook and Twitter, but I use them mainly to share photos of my daily walks through Prague and to check on friends and family and let them know I’m okay. I still use FB Messenger and Twitter DMs, and find these to be good for keeping in touch. WhatsApp, Skype, iMessage and, most recently, Zoom have been a godsend.

To be fair, not everything on social media is bad. The local information shared by Expats.cz and Radio Prague, in English, is useful, and my Prague friend, the BBC journalist Rob Cameron, has set up an excellent moderated FB discussion group on how the epidemic is affecting life in his own part of the city, and the Czech Republic as a whole.

In the absence of any externally imposed structure (like real travel-writing assignments to work on), I’ve tried to create a kind of imaginary daily routine to give my life in the bubble a sense of normality.

In the first couple weeks of self-isolation, I actually did receive a few writing assignments from Lonely Planet. As surreal as it might sound, throughout the month of March, I banged out features on topics like the “Best Nightlife in Prague” and “How to Explore Prague With Kids” --- all the while wondering if any of the places I recommended would still be standing once the tourists return (whenever that will be).

Those features had already been in the pipeline and budgeted for, but my understanding from travel editors is that 2020 will be a very lean year. The two guidebooks I pitched to research this summer -- one on Romania and the other on Hungary -- have been put on indefinite hold. I’m also scheduled to work as a destination expert on a National Geographic Danube River cruise in June, but that’s looking increasingly unlikely. Anyone up for a cruise just now? Nah, I didn’t think so.

So that leaves mostly non-work stuff to build a routine around, and I’ve found a few activities that help me get by.

I’ve written in the past here about how I use meditation to deal with anxiety (and nothing triggers anxiety quite like skimming through a few news articles on coronavirus). I normally budget 30 minutes for daily meditation, but on some mornings, these days, it takes 30 minutes just to quiet the mind. I often go a full hour. I use a basic form of meditation that focuses on counting breaths and doesn’t require any training or special equipment. If you’re interested in trying it yourself, click on this story link to find a fuller description of my method and references to some source materials.

Meditation is not a cure-all, but it does help to restore a sense of perspective. Many people think meditation is about blocking or avoiding unpleasant thoughts. It’s actually more the opposite. In meditation, the idea is to open your mind to all thoughts, including your worst fears and worries. You then let them wash over your brain and release them into the ether. Thoughts can be our worst enemies, and the only way to confront them is to allow them free rein to roam before letting them go.

A pandemic seems like a crazy time to go on a diet, but I’ve also decided to use this self-isolation as an opportunity to lose a few pounds. It’s important in times like these to have some kind of personal goal (even a relatively minor one like this), and I’ve been in denial for a while about the spare tire that’s been slowly expanding around my waist.

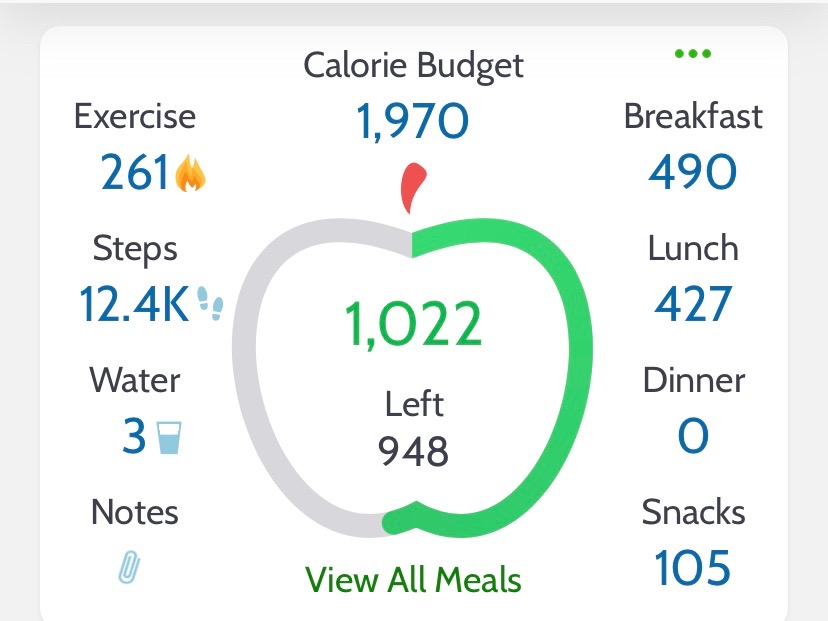

My Prague friend Derek recommended a simple phone app called MyNetDiary that helps to set weight-loss targets, count calories and plan meals. My own target is to lose 5kg (a little more than 10 pounds) by the end of May. To meet that goal, I have to limit calories to 1800 a day.

The app has already helped me to drop a couple pounds, but it’s proven useful in ways I could not have foreseen when I first started. It’s helped me to impose a sense of order on my unruly kitchen, plan once-a-week shopping trips to the grocery store, and ration the food once it’s back home in the fridge. In a more intangible way, it’s given me an added small feeling of control over at least some part of my daily life.

One feature of MyNetDiary is a step-counter on the app’s dashboard that uses my phone’s built in “health” capabilities. I didn’t notice it at first, but once I saw it there on the side, I decided to get back into walking. A few years ago, when step-counting and Fitbits were big, I became obsessive about logging my 10,000 steps a day. I let that lapse ages ago and hadn’t thought about it since.

In the past few weeks, my daily walks around the neighborhood have become the most important parts of my day. During the walks, I binge on podcasts, take photos, breathe in the fresh air (through a mask, regrettably) and marvel at how beautiful Prague is. I return home feeling less overcome and even a little bit restored.

We’re fortunate in the Czech Republic that in spite of the lockdown, we’re still allowed (as of early April) to leave our houses. I know many readers -- in Italy, Spain, Serbia, Romania, parts of the United States, and other places -- are not so lucky. The situation here could change any day. I have a few ground rules for the walks that never vary: walk alone, wear a face mask, and stay at least 2 meters (6 feet) from anyone I might encounter on the trails.

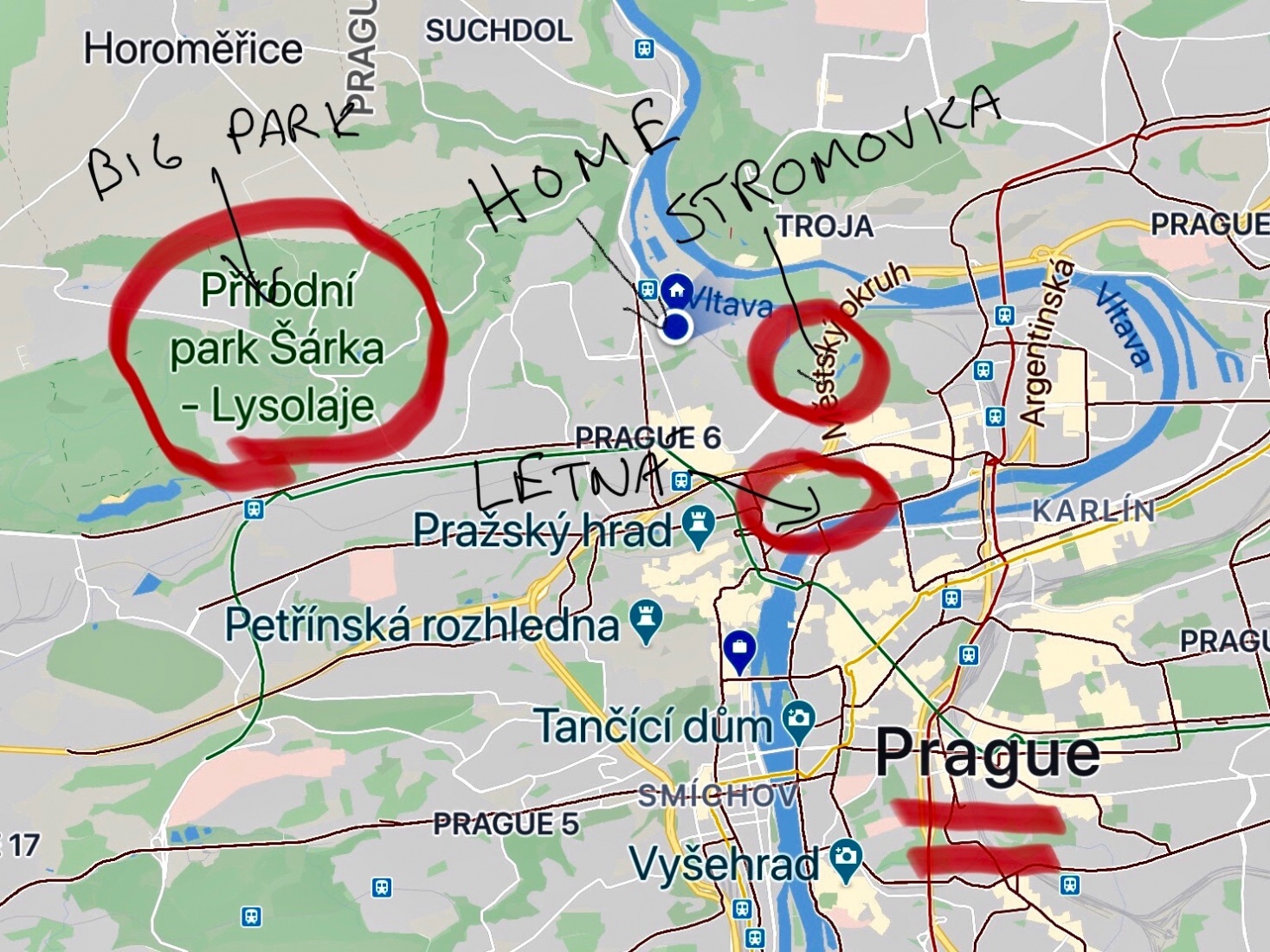

My apartment is in a part of Prague, the far northwestern corner of the center, that’s surrounded by parks and wooded areas (I’ve marked the map above so that you can see what I mean). The Vltava river passes just behind my house along its last zig before it straightens out and heads north toward Germany. The riverbank is relatively isolated in this part of the city and has a little-used gravel path that stretches on for miles.

Several people have reached out to me in recent days for my opinion on how the coronavirus might change travel and the travel industry. The question is often tinged with a feeling of regret or even guilt that coronavirus might be some kind of karmic payback for the excesses that travel has wrought in recent years. The frenzied madness of overtourism, Airbnbs, Instagram influencers, mega-cruises, 20-euro budget flights all over Europe. The path we were on was unsustainable.

Of course, that ignores all the people whose livelihoods are tied directly to the travel industry (including one in every 10 workers here in Prague).

Certainly, for the short term (at least through this year’s travel season) tourism is dead. Czech authorities, for example, have already said that even if life returns to some semblance of normality toward the start of summer, borders with neighboring countries like Germany and Austria are likely to remain closed in order to prevent the virus from re-entering the country. There’s no indication yet how soon those restrictions might be lifted.

For the medium and longer period, I suppose the answer hinges on how severe, in terms of lives lost and economic cost, the pandemic turns out to be. Even in a best-case scenario, I can’t see global tourism revenue in 2021 coming in anywhere close to the 2019 numbers.

In making assessments like this, it’s hard to find useful reference points (the last truly global pandemic was a century ago), but I think back on a strange trip to Croatia I made in August 1997. I’d just accepted an editing job in Prague and had a few weeks off before I was scheduled to start work. I decided to spend part of the time on Hvar, on Croatia’s Adriatic coast.

It’s a popular island at the height of summer and I was expecting to find crowds, but when I got there, the place was deserted. One of the many casualties of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s had been the tourism industry, and though the fighting in Croatia had mostly ended by the middle of 1995, it still took several years for tourists to return. That’s an imperfect analogy, but it might indeed be a while before people -- in large numbers at least -- feel comfortable once again to travel far from their homes.

Whether we will be better travelers -- more responsible and more aware of sustainability issues -- is also hard to say. I’m skeptical when it comes to human nature, so I’m inclined to think any kind of spiritual antibodies we derive from Covid-19 are likely to be short-lived. That’s not to say, though, there haven’t been a few positive signs, as people around the world reach out to help each other. We’ve all learned the value of small freedoms -- to travel, shop, go out, meet up -- that we entirely took for granted only a few weeks ago.

I’ve even noticed some hopeful signs on Instagram (of all places). Instagram, in my opinion, has gotten better (not worse) in the pandemic, and it's one of the few social media platforms I still use. That all-pervasive influencer-driven, #mybestlife vibe of 2019 suddenly feels so out of touch with the current zeitgeist. It’s actually a pleasure these days to swipe through my feed and see inspiring photos of people home-schooling their kids, baking their sourdough bread or whatever else they’re doing to make the best of these trying times.