The idea for this post began – like many do – with a seemingly random exchange online. A friend of mine in Vienna wrote to me on Facebook messenger that she had recently read an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) about the infamous 1952 communist show trial in Czechoslovakia and noticed that one of the defendants, Rudolf Margolius, had lived on Prague’s Veverkova street (though she didn’t know the house number). In the message, she said she wanted to see this street on her next visit to the city.

Veverkova, in the Prague neighborhood of Holešovice, is just around the corner from my office, so I was immediately curious about which building the Margolius family once lived in. The online world can be a magical place (sometimes) and I happened to be connected through Facebook with Rudolf Margolius’s son, Ivan Margolius*, who lives in the UK. I jotted a quick message to him to ask for the house number. He responded a couple minutes later: “We lived in no. 6.” (See map plot, below.)

Ivan and I traded notes back and forth and that’s when I learned about the new documentary (which explains the timing of the NZZ article). He kindly sent me online instructions for viewing the film, and I watched it that same night. The film, in turn, sent me down a rabbit hole that took me to Prague’s Pankrác courthouse and prison, where the trial and executions took place, and to the Margolius family burial plot in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery to see the memorial to Rudolf as well as to Ivan’s mother, the late writer and translator Heda Margolius Kovály. Lurking just nearby was the grave-marker of another well-known writer.

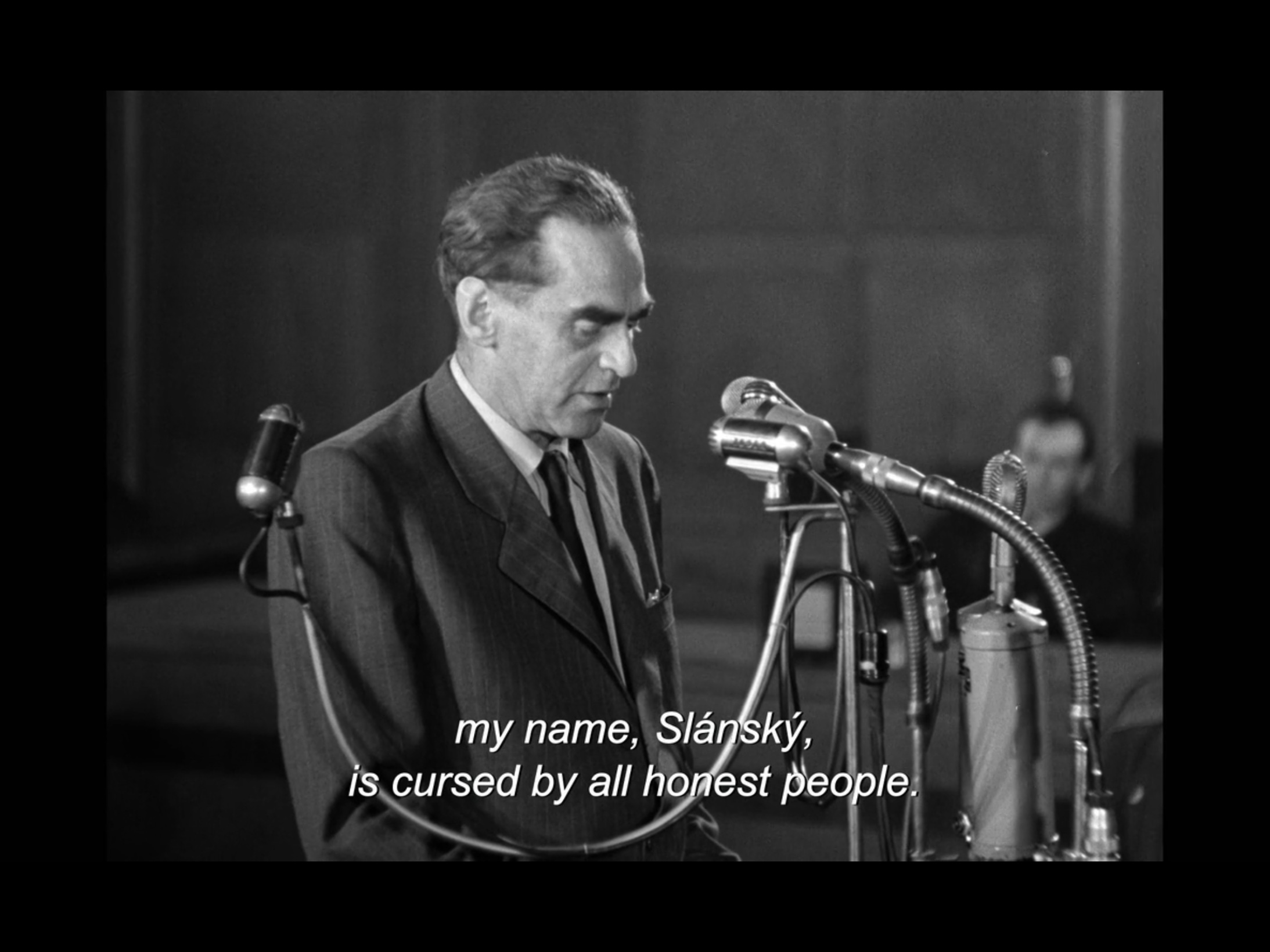

The 1952 show trial was infamous at the time and marked a low point for Czechoslovakia’s post-war communist leadership. The trial’s scope was sweeping. The 14 defendants in total were drawn from all echelons of the government and included two of Czechoslovakia’s highest-ranking officials (and party leader Klement Gottwald’s closest associates): Rudolf Slánský and Vladimír Clementis. The crimes the 14 were accused of were like something out of a fever dream: conspiring to lead an imperialist plot to overthrow the government.

The idea for the trial had apparently come from a group of Soviet advisors that Gottwald himself had invited to come to Prague. The Czechoslovak process coincided roughly with similar high-profile purges in communist-led Hungary of a high-ranking minister, László Rajk, and the “Doctors Plot” conspiracy in the Soviet Union. Similar to the Doctors Plot, where a group of mainly Jewish doctors had been accused of conspiring to kill Soviet leaders, Czechoslovakia’s show trial also had strong antisemitic elements. Of the 14 men accused of plotting to overthrow the Czechoslovak government, 11 were Jewish.

Stalin’s fingerprints were all over these trials, but it’s still not entirely clear to this day why they happened at all. In the 1930s, Stalin had used a series of similar, high-profile purges to instill deep fear and uncertainty within the Soviet leadership. Perhaps Gottwald, on some level, had feared his own position was in danger and wanted to eliminate any potential rivals. The timing of the trials probably also played a role. Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito, not long before, had decided to take his country out of the Moscow-led Soviet bloc. The newly formed Israeli state, at the time, had also opted not to align with Moscow. Both developments infuriated Stalin. Tellingly, the Czechoslovak defendants were all variously accused of being pro-Tito, Zionist puppets. Most probably, Stalin by that time had simply lost his mind.

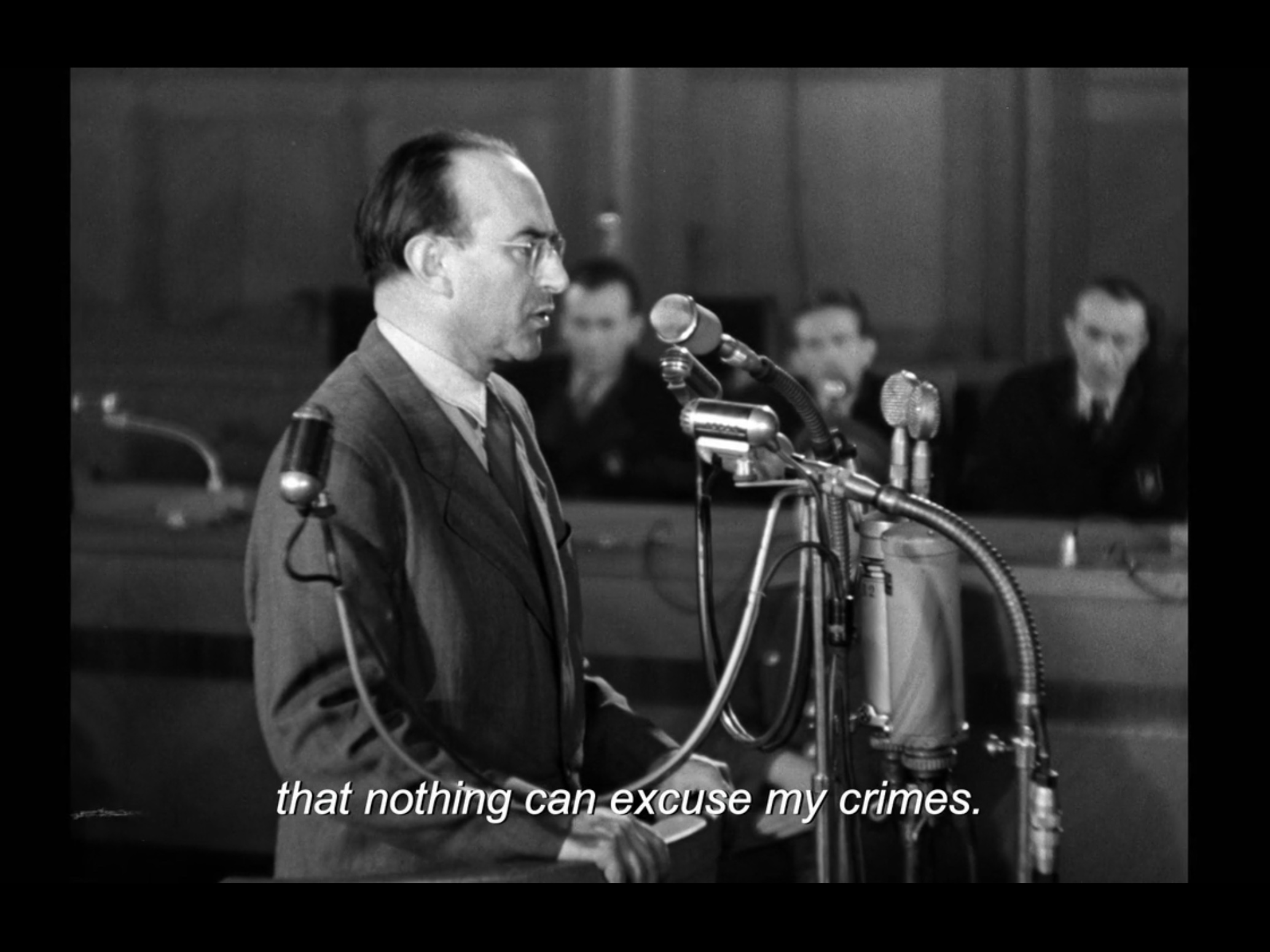

Slánský and Clementis – as well as some of the others -- were long-time communists and certainly guilty of countless crimes against humanity, but none of the 14 was actually guilty of the crime they were being tried for: orchestrating an imperialist coup. Rudolf Margolius, at 39, was the youngest of the defendants, and as a relatively low-ranking deputy minister of foreign trade was arguably furthest removed from any real power. He was surely innocent of any serious crime. It’s unclear to this day why (aside from simply being Jewish) he was ever brought into this charade at all.

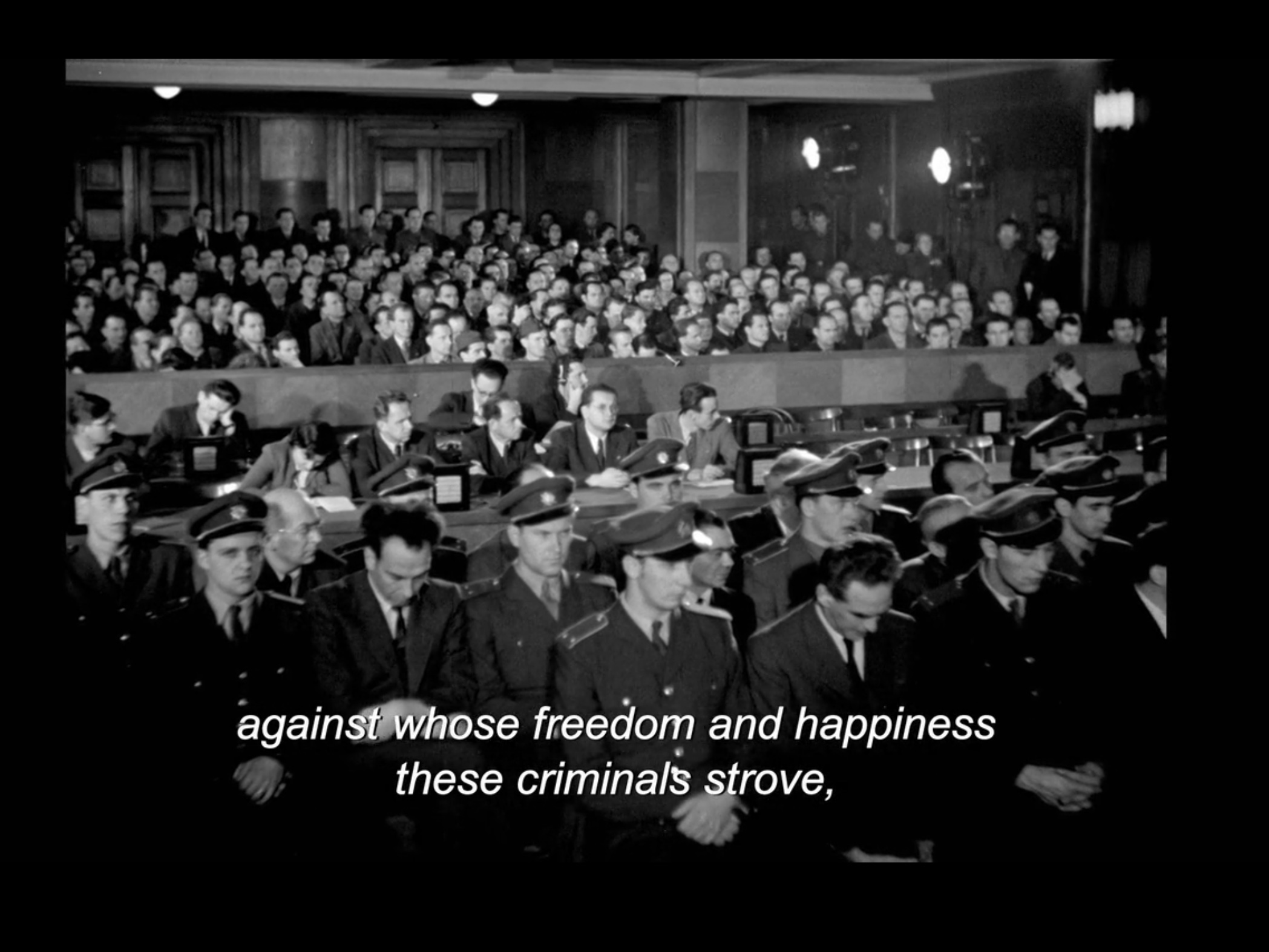

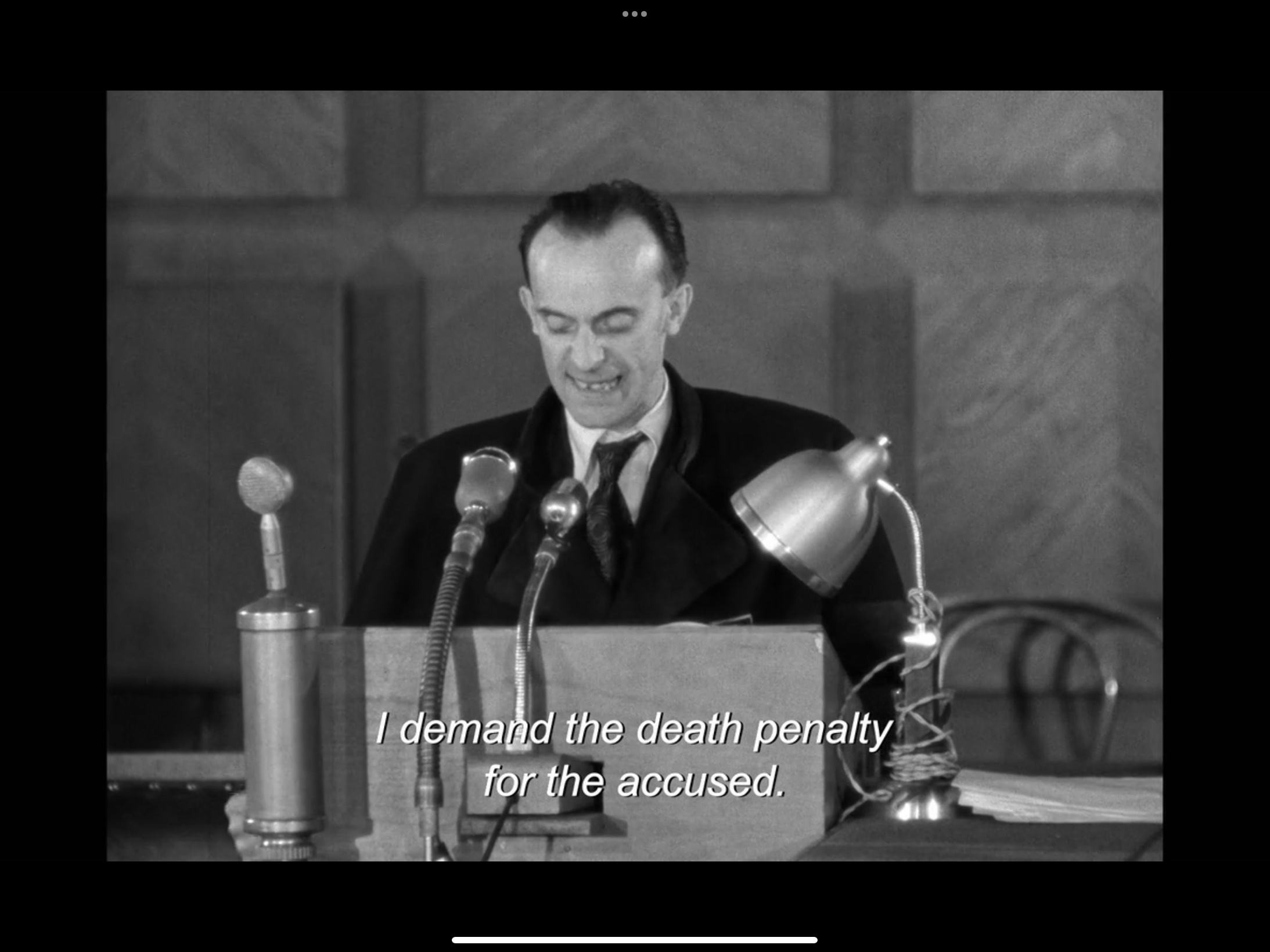

The defendants were arrested during late-1951 and early-’52. They were held in custody at Prague’s Pankrác prison, tortured for days and weeks at a time, and ultimately broken into signing confessions that proved, in the absence of any physical evidence, crucial to the prosecutors’ case. The men were forced to learn by rote the damning responses to the charges they would face in the process, which took place at the adjacent Pankrác courtroom in November 1952. There, they would faithfully recite their answers for the benefit of the cameras and posterity. The men carried out these instructions to the letter. It was a show trial in every sense of the term: an artless piece of political theater.

All of the men were eventually found guilty. Eleven were condemned to death and hanged at the prison. The three remaining defendants were given life sentences.

“Le Procès – Prague 1952” is an amazing film that skillfully weaves the recovered archive footage of the trial with interviews with surviving family members of three of the defendants. The trial scenes are mesmerizing. I found myself staring at the faces of the condemned men as they stood at the microphone and read aloud the lines from their forced confessions – and tried to process in real time the surreal nature of what was happening to them.

As I watched, I thought back to Koestler’s book, “Darkness at Noon,” where the author digs deep to try to comprehend the confounding motivations for how a condemned communist might come to accept and even agree with his accuser’s fantastical, heinous allegations. Koestler ultimately landed on a kind of “Stockholm Syndrome” – let’s call it “Moscow Syndrome” – where the prisoner ultimately comes to accept and embrace the pretzel logic of his captors that his death is necessary for the party to achieve its aims.

I’m not sure if any of the defendants ever got that far (it’s hard to read too deeply into their dazed expressions as they admit their crimes). What comes through clearly, though, is the trumped-up, sham nature of the entire affair, the hatefulness of chief prosecutor Josef Urválek, and the chilling bloodlust that was evident in the courtroom and in the wider Czechoslovak society. Whether members of the general public truly believed the sensational newspaper reports that the defendants were guilty or were simply too afraid to speak out, it’s obvious that many people from all across society were totally, depressingly, down for this trial.

Ivan himself plays a prominent role in the film – along with surviving relatives of two of the other men -- as he shares his earliest memories of his father and reads from a touching letter Margolius left him from his last days in prison. In the letter, Margolius freely “admits” to his guilt and urges his young son to be the best person he can be and to act in the best interests of his country. I can’t speculate on his reasons for writing what he did, but perhaps he thought that if he disputed the charges the letter might never be delivered or that he might cause his family even further pain or difficulty. It’s a sad and highly moving moment.

As fascinating as the movie is, it only recounts part of the remarkable life story of Rudolf Margolius and his wife, Heda. Details that make the trial all the more tragic.

The two were married in Prague in 1939, the year Nazi Germany invaded and annexed part of then-Czechoslovakia. Both were rounded up as Jews in 1941 and transported to the Nazi-run ghetto in Łódź, Poland. Both were eventually taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau and to subsequent concentration camps during the war. Both, remarkably, survived that horrific ordeal and returned to Prague in 1945. Heda writes about this (and the trial and what came after) in her gripping memoir, Under a Cruel Star.

Indeed, Margolius’s haunting experiences in the camps may help to explain his tragic decision to join Czechoslovakia’s communist government and ultimately the dignified and humbled manner in which he accepted his fate. Writing about Margolius, the prominent Czech exiled journalist and anticommunist, Pavel Tigrid, noted that because of what he had seen and lived through in the camps, he’d become an idealist. “Margolius enrolled in the party from the genuine conviction that … never again would someone be persecuted for his or her racial, national or social origins … and that all people would be equal.” Tigrid continued: “A couple of years, later the comrades succeeded where the Nazis could not -- they killed him.”

During our Facebook exchange, Ivan encouraged me to visit the Margolius family burial plot in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery – not only to see the memorials to both Rudolf and Heda, but to witness what he called a “true Prague absurdity.”

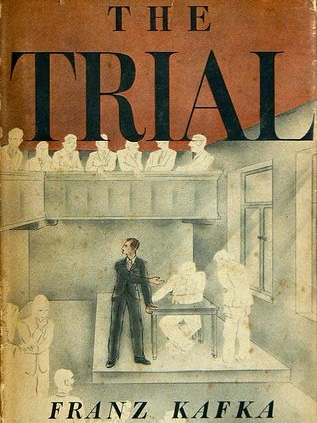

Once I saw the plot, I knew exactly what he meant. Just behind the family burial ground – immediately adjacent to Rudolf Margolius’s own memorial -- stands the instantly recognizable grave-marker of Franz Kafka, the author, of course, of “The Trial” among many other acclaimed novels and stories. In that book, a character named “Josef K” famously stands accused and condemned by an unknown authority of committing crimes that are never clearly articulated and that he never truly understands. I was gobsmacked. The ironies are so dense they’re hard to wrap your head around.

Ivan told me the position of the markers was pure chance. When his great-grandmother died in 1922, the rows were being filled in. By the time Kafka died two years later, his burial spot landed just behind theirs. Still, it’s the kind of coincidence that instantly makes you wonder whether pure chance exists at all. Maybe everything really is simply foreordained.

In 1963, following the long de-Stalinization process that came in the wake of Stalin’s death a decade earlier, the trial defendants were all formally exonerated of their crimes. In 1968, Rudolf Margolius was awarded the Czechoslovak “Order of the Republic.” Still, Ivan told me, his family has never received an official apology from the Czech government. After viewing the film and learning more of the family’s story, that strikes me as something now long overdue.

(Scroll past the map for more photos.)

*Ivan Margolius recounts this family history in more depth in his book, ‘Reflections of Prague.’ Click here to find a link.

Like Ivan, I live in the UK since 1968. Like Ivan, my father (and mother) were imprisoned in early 1950’s and despite torture and pressure, refused to admit their “anticommunist activities”. That saved them from the main Slansky trial, but my father was sentenced to 15 years in the Svermova trial. My mother was released after two years “for insufficient evidence” but never rehabilitated or compensated. I have also published a book, a child’s memories and views of the times, how I coped with adversity, deprivation and discrimination, without lasting bitterness or damage. There are many many lives marked by history, Margolius family stands out. And thank you for pointing out the proximity of Kafka and Margolius’ graves, next time I am visiting my parents, I will pay my respects.