The year 2000 found me working as an editor at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and living in a pricy apartment building a couple of blocks off of Prague’s Old Town Square. Even back then, the crowds in the center were beginning to get unmanageable, and I was desperately looking to relocate somewhere that was cheaper, quieter and more normal. After looking at places all around the city, I decided on a one-bedroom flat in a three-story walk-up on Čechova street in the district of Holešovice, north of the Old Town across the Vltava River (Čechova actually lies just outside Holešovice, but it’s organically connected to that neighborhood, so please just ignore that for now).

I was fairly familiar with Holešovice back then, so it wasn’t exactly a radical move. Readers of the blog might remember I was one of five expats who opened a bookstore and coffeehouse, The Globe, in Holešovice back in 1993. But the Globe was located in a different part of the district from my new place, and I was looking forward to discovering what felt like a brand new hood.

The neighborhood proved to be perfect for the seven-year stretch I lived there. The best things were the two big parks nearby: Letná (with its laid-back summer beer garden) and Stromovka (with its cycling and jogging tracks). Čechova and neighboring side streets were filled with casual bars and restaurants. I could almost fall out my door and into a pub (or more practically out of a pub and into my door), which by Prague standards means I’d found an excellent place to live.

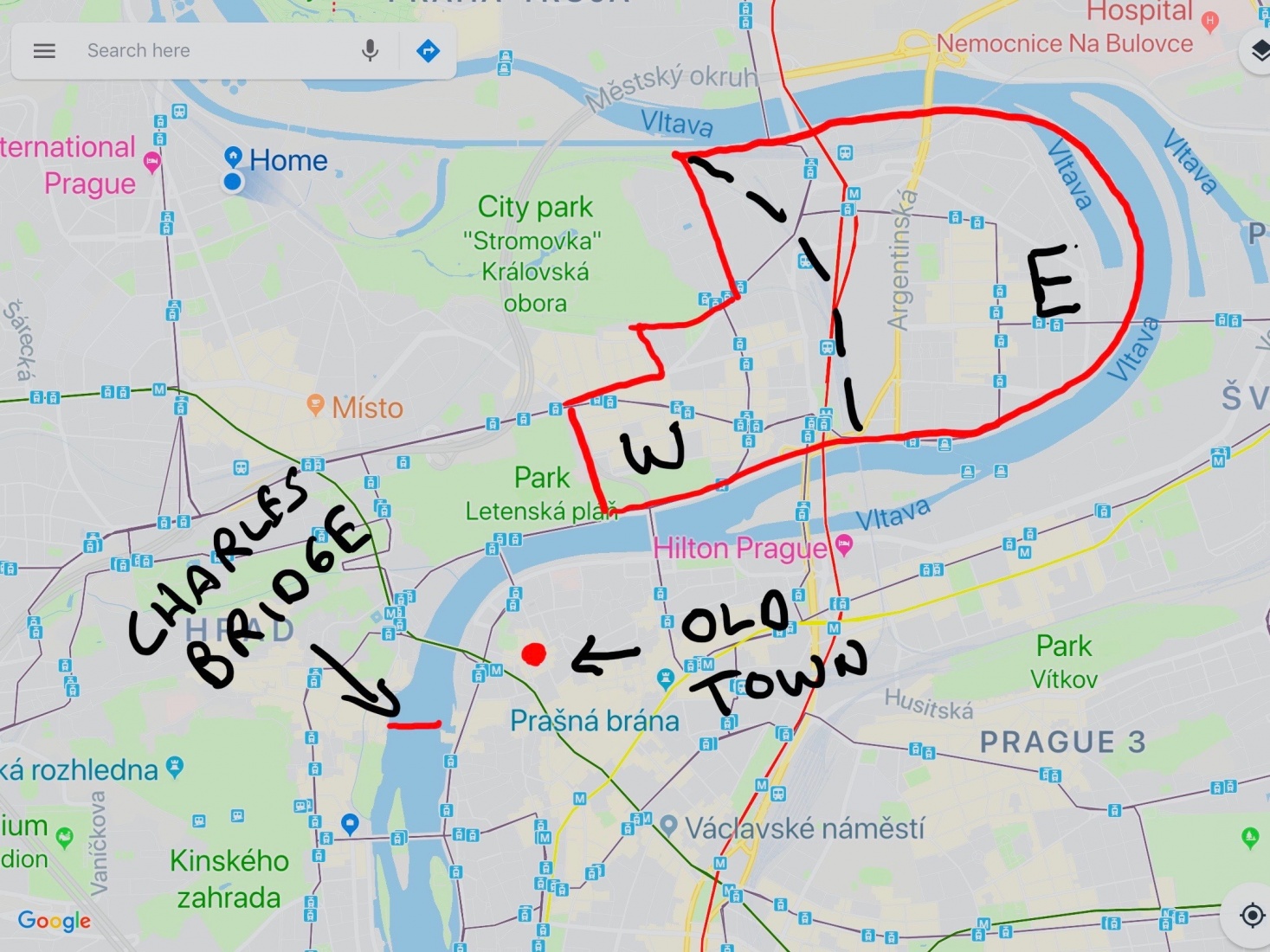

In time, I stretched my knowledge of the neighborhood several blocks to the east (a quick look at the map shows Holešovice to be a long, bulbous district that hugs the northern bank of the Vltava for several kilometers before the river bends back westward). What I found was essentially a gritty, workaday neighborhood -- part industrial, part residential -- that felt like the perfect antidote to the daily circus taking place down on Old Town Square.

When you live in a place long enough, and this includes living in a particular Prague neighborhood, you naturally start to identify with it and it slowly begins to tug at your loyalties. Over time, I became what you might call a “Holešovice” person, and even though I no longer live there, that identification endures. Neighborhood loyalties come as second nature in Prague and may even be more important to expats than native-born Praguers. They help you locate yourself somehow in a city and culture you might otherwise have only a tenuous connection to.

So, what’s a Holešovice person you might be asking? That’s hard to say.

My friends in Vinohrady are going to kill me for this, but let’s put it out there and see what happens. In Prague -- generally speaking -- you’re either a “Vinohrady” person or a “Holešovice” person (though you could easily substitute any other depressed district in place of Holešovice, like Smíchov or Žižkov).

Vinohrady, like Holešovice, is an outlying Prague district that grew up in the 19th and early 20th centuries as the city expanded beyond its medieval extents. Unlike Holešovice, though, Vinohrady never suffered through an awkward industrial phase and from the onset always managed to attract upwardly mobile, professional people to live there. It’s a district of tree-lined streets and well-kept apartment blocks.

These days, Vinohrady people like their cronuts just so. They tend to be too exhausted by choice to care overly much about the new café or craft-beer joint that just opened up around the corner. They don’t bat an eye at a 200Kč ($10) pour for a tiny glass of mediocre white at fancy places like Aromi on the district’s main square, Náměstí Míru.

Holešovice people (at least until gentrification began to encroach) are pretty much the opposite. They keep it real. The area’s arid blocks (particularly in the isolated eastern half) retain an old school, outer-district feel: a scruffy tobacco shop, followed by a Vietnamese grocery, a butcher’s, and a pub or “herna bar” -- Czech slang for an after-hours joint where you can play the slots. While Holešovice has always had a few edgy clubs or destination restaurants, including the bunch located by my old apartment on Čechova, an evening out usually meant a lackluster schnitzel followed by a few beers afterward at a stinky, old-man’s pub.

And that suits me just fine. (Besides, I can always cross the river over to Vinohrady to find something decent to eat.)

The more you get to know Holešovice, the more you realize the district suffered through some tough breaks over the years. There's definitely some PTSD going on.

Let’s start with physical geography. The planners who laid out the district in the 19th century were unusually cruel. An old railroad line passes straight through the middle of the neighborhood, splitting the district like a lobotomy into a still rough but gentrifying western side (including my old neighborhood at the far-western end) and a tough-as-nails, cut-off-from-humanity eastern rump.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, the Communist planners finished the job, planning highways, flyovers and concrete no-go zones along the railroad corridor that effectively make it impossible to walk from one side of the district to the other.

And then there’s history. For years, Holešovice suffered under a cloud of bad karma. During the Nazi occupation in World War II and the years immediately after, some of the worst atrocities to ever take place in Prague happened here.

From October 1941 until the nearly the end of the war in March 1945, the occupying Germans used Holešovice as both the main assembly point and departure station for shipping off the city’s Jewish population to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt (Terezín) (many ended up eventually going to Auschwitz-Birkenau) or to the Jewish ghetto in the Polish city of Łódź.

The process was relatively straightforward. Jewish families would receive an order to assemble at what was called the “Radiomarkt” (Radiotrh in Czech), near where the Park Hotel stands today, where they would be arranged according to transport numbers, stripped of their belongings, and ultimately marched off to the Bubner-Bahnhof (Praha-Bubny train station), about a kilometer away. During those four years, more than 45,000 Jews passed through the Radiomarkt on their way to the camps. There's now a small memorial at the station to mark the deportations.

Then, in the months immediately after World War II, Holešovice -- which traditionally had a large German population -- became a focal point for the forced expulsions of Germans by Czechs in retaliation for Nazi crimes committed during the war. From the end of the war, in May 1945, through 1947 or ’48, something like 3 million Germans were forcibly expelled from Czechoslovakia to points in both western and eastern Germany -- part of Europe-wide phenomenon that’s been described as the largest ethnic cleansing in modern history.

Innocent-looking Strossmayerovo Square, the district’s biggest public space and tram junction, was once the main assembly point for Germans before being kicked out of the city. While researching this post, I found an article in The Guardian that quotes one of the former expellees, a woman named Eva Honzejková, as saying she saw German bodies piled high in the courtyard of the district's Bio Oko cinema not long after the war.

It’s not surprising, then, that Holešovice languished for decades -- and might be languishing still if it hadn’t been for the good fortune of a once-in-100-year calamity in 2002 that ultimately helped turn the place around.

The Holešovice I've been writing about so far is the Holešovice that was ... and probably the one we'd still have if something strange hadn’t happened in August 2002. Freakishly heavy rains that summer pushed water levels on the Vltava beyond the breaking point. Containment dams upriver could no longer hold the swell and several low-lying Prague districts, including parts of Holešovice, suddenly found themselves inundated in the worst flooding since 1890.

My place on Čechova street was on higher ground, so I was spared the drenching (in fact, I even took in a flood refugee for a few nights), but many parts of Holešovice, particularly the Vltavská metro station and neglected eastern Holešovice, were not so fortunate.

Instead of stewing in all that mildew, though, to their immense credit the district officials resolved to turn a corner: to use the destruction as an opportunity to reimagine the district afresh. From that moment on, Holešovice has been on a slow, steady upward march.

As a travel writer, I’d hate to oversell Holešovice. Most visitors, after spending a day tramping around the district, would likely have enjoyed the chance to see "real Prague" away from the tourists but could still be forgiven for thinking: “where’s the beef?” Residents, however, know the progress has been remarkable.

And there are several highlights, including the National Gallery’s collection of Modern & Contemporary Art at the Trade Fair Palace, that absolutely shouldn’t be missed. The city is hoping to pair the museum with the DOX Center for Contemporary Art as a way of leveraging Holešovice someday into Prague’s “Art District.”

Visitors with children will also want to check out the planes, trains and automobiles on display at the National Technical Museum on Holešovice’s western end. As a reward, stop by afterward at the nearby Letná beer garden for an outdoor beer in a plastic cup and a 100-like (guaranteed) Instagram shot of Prague’s Old Town across the Vltava.

Call it a happy coincidence, but just as the initial phase of the post-flood reconstruction was starting to lose a bit of steam, around 2010, hipsters came along and reinvigorated the process of converting the district’s disused warehouses and abandoned factories into performance spaces, cafes, restaurants and clubs. New places are popping up all the time and the future looks bright. Modern aesthetics continue to evolve and we’ve all begun to see a bit of beauty in unvarnished authenticity – and whatever else it might lack, Holešovice has authenticity in spades.

I’ve used the photos to highlight some of my favorite cafes and restaurants these days. Scroll past the map to see more images.

Cool. That’s my hood when I live in Prague. Good job and the photos are great.

Great article. I know the area as have stay at a hostel Sir Toby’s in the area a few times.

Great minds…! Wonderful evocative piece. We had to be brief and utilitarian but here’s what we’ve published a month ago:

https://issuu.com/prague.eu/docs/web_a_issuu_hol_letna

Thank you! This brochure looks great and beautifully done. I will stop by sometime and pick up a copy in person

Grew up in Holesovice.My beloved home! My school is still in there in Jablonskeho just across from metro station and Holesovicke nadrazi.

Hi Jana, great to hear. Holesovice is changing quickly but it’s still that grubby place we all love 🙂

Fascinating and informative piece, Mark – thank you (I’m insanely envious of people who do this kind of stuff bilingually, by the way!) Just a couple of thoughts on reading: I’m pretty sure Park Hotel is actually a child of the sixties – 1967 I think. Also, I’m sure you know this, but it may be of interest to others: Vltavská metro was one of several grungy locations, including Vršovice (mon amour) to feature in the recent Apple ad for the iPhone XR!

HI Alex, thanks for reading and leaving a comment. You’re probably right about the Park and that’s a cool fact about Vltavska that I didn’t know!

Always a nice reading and great insights, Mark! Looking forward to visit Prague again soon.