I was really looking forward to stopping in at the newly renovated Czech National Museum, that aging, grandiose building that stands at the top of Prague's central Wenceslas Square. The museum was closed back in 2011 in order for the building to get a long overdue overhaul. It’d been shut down for more than seven years.

The scheduled re-opening, late last year, was timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Czechoslovak state on October 28, 1918. Unfortunately, on October 28, 2018, I was far from the action, researching cities in Bulgaria for Lonely Planet. I could only admire the whole thing from a distance.

When I got back from Bulgaria, in November, one of the first things I did was to hustle my way down to the square to visit the museum, but the line to get in stretched outside the door and around the building. The museum’s administrators were obviously so proud of the renovation that they wanted everyone to see it and had opened the doors to the general public for free.

Oh, screw it, I thought. I’ll just go back later and pay my own way – at least I’ll have the place to myself.

A little background about the National Museum before continuing with the story. It’s one of those buildings that by sheer size and pomp holds itself up to a certain amount of ridicule. The scale of the immense Neo-Renaissance building (from 1885-91), and its position overlooking the city’s most prominent square, reflects the museum’s foundational aims of going beyond merely housing exhibits on natural history and folklore. The museum was originally conceived as a celebration and projection of Czech nationalism, and that's what it looks like.

There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. All around Europe in the 19th century -- in the wake of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s incursions into the continent -- peoples and cultures were re-awakening and staking out their various nationalist aspirations. The Czechs, for their part, had suffered through an especially long ride under the Austrian Habsburgs and were more than ready to make their national debut.

The problem only came later when the museum finally, truly settled into its role as a museum – and a kind of middleweight one at that. The massive building always seemed a little too gaudy and grandiose to hold what, admittedly, was a dusty, 19th-century collection of gemstones, butterfly wings pinned to paper, and dinosaur bones.

When the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, Russian soldiers famously fired on the museum believing that it was the Czechoslovak parliament. It’s obviously an outrage to be invaded by another country (and I don’t want to belittle that in any way), but I’ve always thought the act of shooting the museum sticks in the Czech craw so much (to this day) because it’s also slightly embarrassing. I mean who puts a history museum in such a prominent location?

Although travel writers (and lots of others too) teased the building a bit, I always had a soft spot for the old museum. I didn’t visit often, but when I did, I enjoyed getting lost in those musty rooms and pouring over endless cabinets of fossils and crystals and minerals. I liked the way the big doors and floors creaked, and how the hallway minders seemed to follow you into every empty room, intently watching that you didn’t break the glass and make off with a desiccated African beetle or something (I mean why else would you be there if not to steal something?)

I much prefer those old-school museums to the new interactive ones where you’re constantly bombarded by lights and noise and end up sitting through 20 or more videos before it’s all done. My friend Kateřina put it this way when I told her the story: the old National Museum was a museum of how museums used to be. And that’s fine with me.

I’d also recently visited the National Museum's sister institution in Vienna, the Museum of Natural History, and had enjoyed an absorbing tour of the place by one of the curators, Dr. Ludovic Ferrière, of their celebrated meteorite collection. I was definitely in the mood for more stones and bones in Prague.

And that’s when it got a little strange.

On arrival, I didn’t notice anything unusual at first. The museum wasn’t exactly heaving with people, but then I’d purposefully chosen a Wednesday afternoon to avoid the crowds. I did hear smatterings of English and French as I walked around, but Prague’s not especially overrun with visitors in January. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary.

I plunked down my admission (a fairly hefty 250 crowns - 10 euros - around double the old price and five times what it was in the 1990s) and walked inside.

The first thing visitors will see -- and this won’t disappoint at all -- is the spacious entryway and the marbled, carpeted stairways that lead to the upper levels. It wasn’t all that different from the old museum, but the room felt cleaner, lighter and fresher -- and probably closer to what the building’s architect, Josef Schulz, had intended in 1885.

I noticed that there was a temporary exhibition -- on “100 Years of Czechoslovak Statehood” -- on the ground floor toward the back, but I made a mental note to save that for last -- and only if I had time. First, I wanted to take in all those older exhibits that I had remembered from at least a decade earlier, and see how the curators had chosen to display them for a new generation of visitors.

I scrambled up the stairs to the first upper floor and started to push in on the big wooden doors that led to the various exhibition rooms. Some were locked while others gave way to spaces that were either mostly empty or filled with ladders and buckets. The third floor was exactly the same, and then slowly it dawned on me.

The National Museum was a mere shell of a place. A nothing-burger. A Potemkin village. Aside from the staircases, there was actually nothing to see -- none of the exhibits were there. Not even the butterflies! It had never occurred to me that they might re-open the museum but not restore any of the old exhibits, but that's apparently what they'd done.

I later learned the whole story and now it makes more sense, but at that point I still had no idea what was going on. Here's what happened: Apparently, the October opening was only a "partial" one in order to meet the deadline for the 100th anniversary and to show off some of the initial restoration efforts. The administrators now plan to close the museum again fairly soon and re-open it with all of the original contents in place either later this year or sometime in 2020.

I know, my bad. But to be fair, I wasn't the only one there who'd never gotten the memo. In fact, it was fun to catch people’s eyes the moment they realized they’d been had, as it were. (And what exactly were they charging the 250 crowns for?)

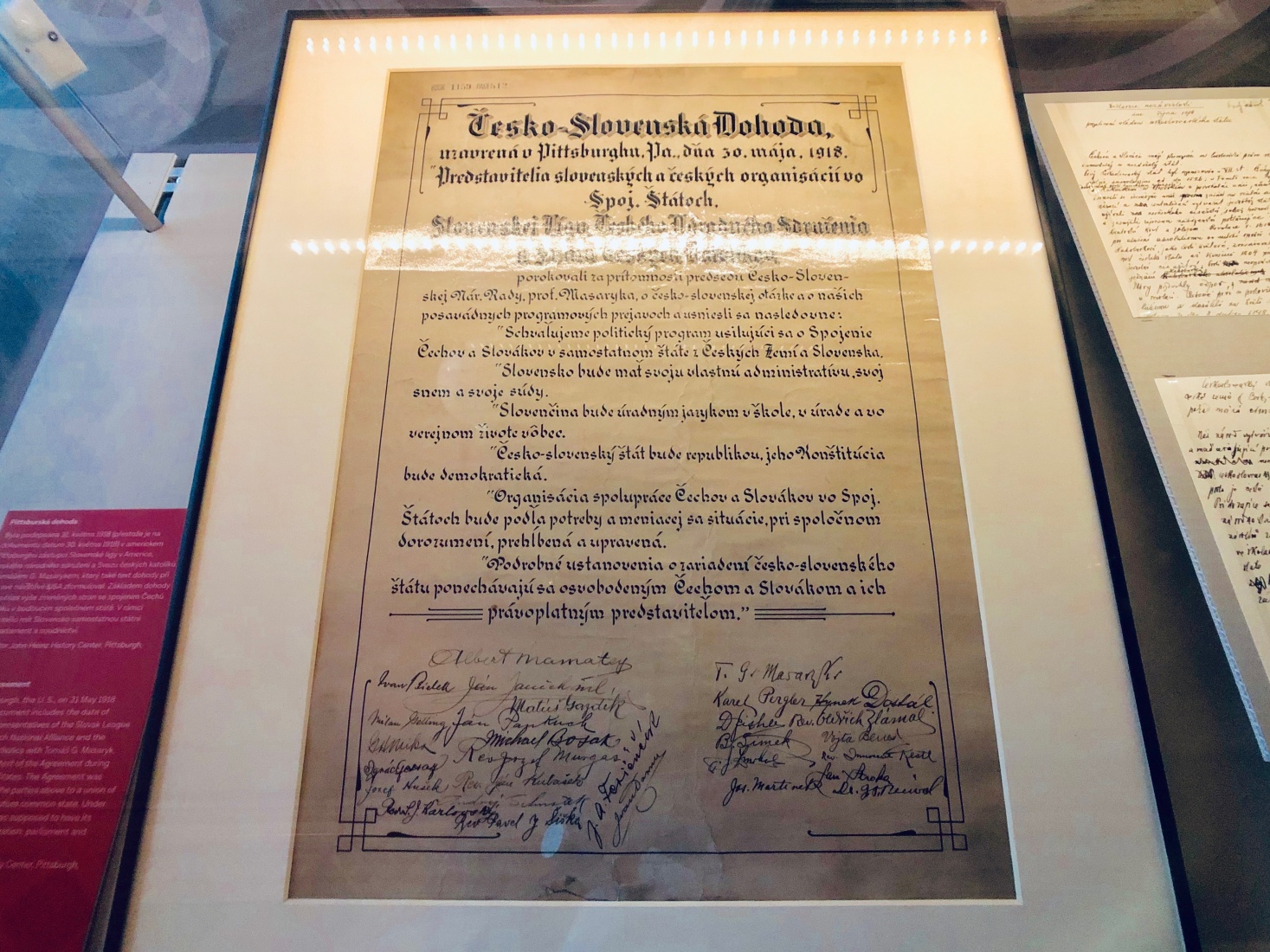

To be fair, the place wasn’t entirely empty. There was that exhibition on Czechoslovak statehood on the ground floor. Trying to recoup part of the ticket price, I took a walk through that. What I found was a bland, mostly upbeat rendition of the country’s origins that adhered pretty closely to the mainstream (and studiously avoided any uncomfortable questions). I’d love someday to see an exhibition dedicated to exploring the issue of communist-era collaboration, or the expulsion of Germans after World War II, or the enduring, underlying tensions between Czechs and Slovaks -- but this show obviously (and understandably) didn’t want to stray too deeply into those uncomfortable topics.

I stumbled around a little longer, paid one last admiring glance at those staircases, wandered my way outside, and then had a good laugh. Prague had somehow managed to surprise me all over again, and as usual the joke was on me.

I posted a shorter version of this story on my Facebook page and a Czech friend admonished me slightly, saying I could have avoided this whole experience by simply googling the museum website ahead of time. Maybe she’s right, but I’m not sure many people would google a museum just to make sure there’s going to be something to see there. And besides, the National Museum’s website is not very explicit about what is and (crucially) what’s not on display. Mark

On that same Facebook post, another friend left this thoughtful comment. I hadn’t considered the “Victorian time capsule” aspect of the museum, but he makes what I think is a good point (though I think and hope that those wooden cases are coming back):

Thanks for sharing, Mark. I haven’t been inside yet, although I’ve had my deep concerns that the old “bones and stones” aesthetic that I loved dearly — and have visited many times over the years — would be lost. Just a few days ago, I was in the Peabody Museum in Harvard which, along the museums of natural history in Paris and New York are wonderful time capsules of Victorian science which should be preserved on their own terms. In a word, I’m depressed to learn that all the taxidermy and whale skeletons have been removed, I suppose along with the beautiful wooden display cases.

Thanks for posting this. I read (I believe over the summer) last year that during the cleaning process of the gems and other artifacts, they discovered that many of the gems were fake. I assume they will not put those back on display, but I believe beyond being cleaned everything is also being appraised and investigated for their authenticity.

I’m visiting in March. Do you think the museum will be open?

Hi Jacob, thanks for visiting my site and leaving a comment. I believe the plan is to have the museum open by March, but it’s no guarantee. At each stage in the reconstruction process, they’ve missed deadlines, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all if they delay the re-opening into 2020. About the fake and missing gems, that’s a fascinating story. Here is a link to a longer piece: https://www.thediamondloupe.com/world-news/2018-03-09/czech-national-museum-finds-its-precious-gems-collection?fbclid=IwAR208h6a6MDo6K5DicoSPIcL4laMlBTmMXAyJxzP5zbgcHQEvRVShs1uoAY