Just to get this out of the way right off the bat. I wasn’t initially in favor of the U.S.-led attack on the Taliban -- “Operation Enduring Freedom” -- which began in October 2001, a month after the al-Qaeda strikes on New York and Washington. I understood the reasons for the war, but I favored treating the terrorist attack as a criminal act and not as a sovereign “act of war.” I didn’t want to see the U.S. Army get bogged down in difficult terrain in an unwinnable fight. It wasn’t that long before, after all, that a war in Afghanistan had practically bankrupted the Soviet Union.

No one, of course, asked me my opinion, and I watched along with everyone else with a mix of hope and fear as U.S. and British warplanes first bombed Taliban and al-Qaeda strongholds in a series of aerial attacks, and then as anti-Taliban Afghan ground forces, in conjunction with elite units from other NATO countries, retook key cities like Kabul and the northern city of Mazar-e-Sharif. Despite the botched effort to capture al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in December at Tora Bora, by the end of 2001, the Taliban had effectively surrendered and its leader, the one-eyed Mullah Omar, had gone into hiding.

In a matter of a few months, the Taliban had been defeated, al-Qaeda pushed out and a new provisional government, more reflective of Afghanistan’s mix of cultures and ethnic identities, installed in power in Kabul. Afghan women and girls could now go to school, men could shave their beards, and everyone could fly kites again. It had gone better than anyone dared hope.

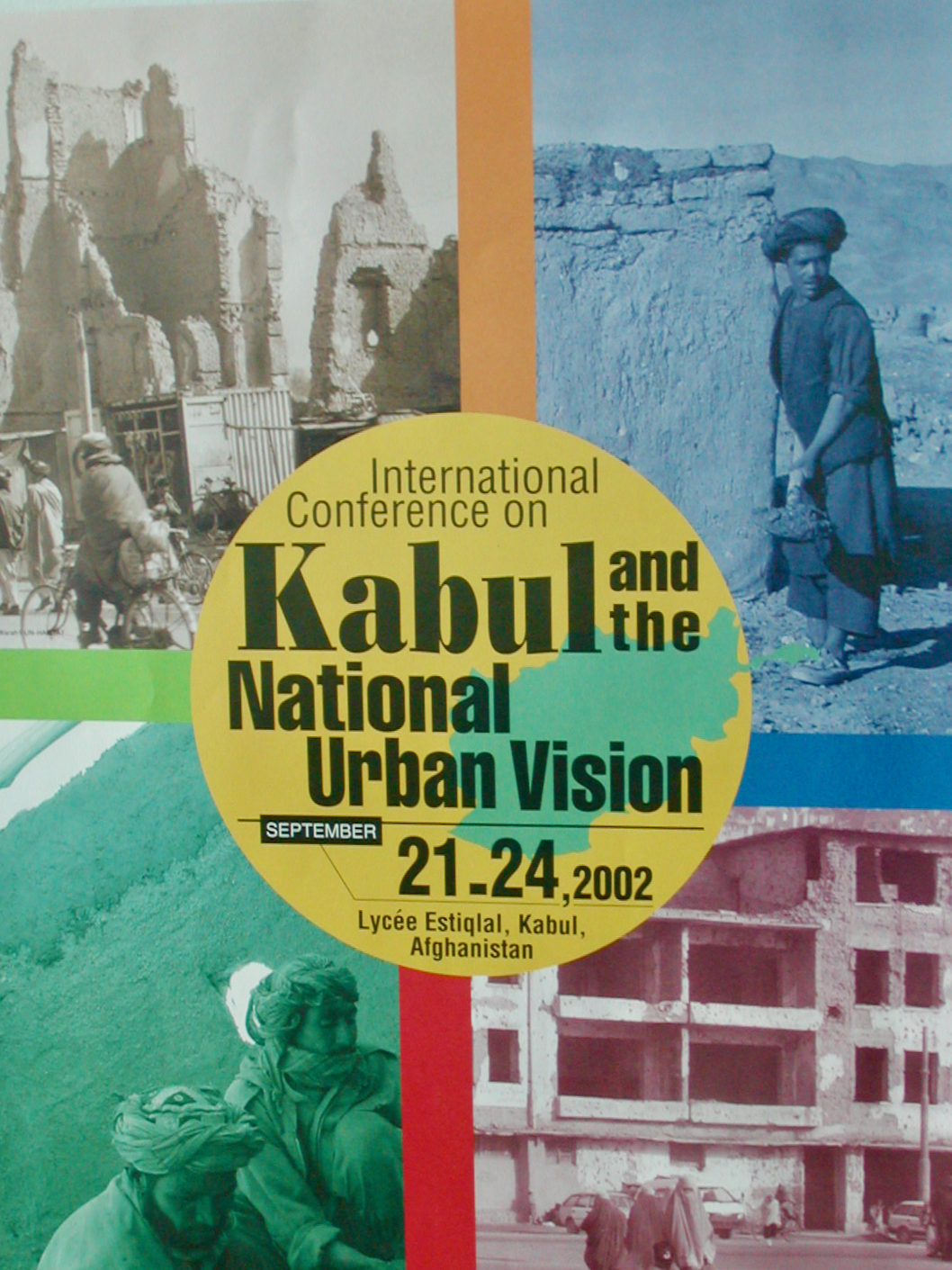

My Afghan assignment began in early September 2002, after most of the heavy fighting had stopped and just as that initial wave of post-Taliban enthusiasm was cresting. International aid organizations poured into the country to start the process of rebuilding Kabul, which suffered extensive damage during the Afghan civil war of the 1990s, and repairing the country’s roads, schools and hospitals. The war to push out the Taliban had been a big story for us at RFE/RL (and our colleagues at Radio Free Afghanistan), and the practice in our newsroom at the time was to rotate correspondents from a pool of editors and journalists for a month of on-the-ground reporting. While I normally covered more-mundane topics, like economics and politics, sometime in the summer of 2002 my boss called me into his office and told me to get my paperwork and vaccinations in order. “We’re sending you to Kabul.”

The timing of the assignment was fortuitous. I wouldn’t be covering a hot war, but rather the aftermath of the conflict and the happier story of rebuilding the country. I was still a little apprehensive, though. Random street bombings were relatively common (an explosion in Kabul’s central market killed more than 30 people a couple of days before I arrived). Even scarier, earlier in 2002, an American correspondent for “The Wall Street Journal,” Daniel Pearl, had been abducted in the Pakistani city of Karachi and beheaded by a shadowy terrorist group that called itself the “National Movement for the Restoration of Pakistani Sovereignty.” Pearl’s murder affected us all profoundly. The “war on terror,” after all, was at its height and Pearl could have easily been any one of us.

There were no commercial flights at the time into Kabul, and the standard practice for traveling to Afghanistan was first to fly to Islamabad, Pakistan, and then hitch a ride on a UN relief flight out to the country. The wait for a seat on a UN plane could take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks. My trip began with a major stroke of luck. I managed to snag a UN seat just three days after I arrived in the Pakistani capital.

To this day, I’ve never experienced a place that felt quite as menacing as Islamabad. Maybe I was still spooked by Danny Pearl, but as I walked around the city on that first day, I couldn’t help but notice the hard stares I got from guys standing around in the streets. I had never felt both so foreign and so despised at the same time. My “welcome” to Pakistan began earlier that day, just after my connecting flight from Dubai touched down at Islamabad airport. As I bent over the luggage carousel in the arrivals hall to fetch my suitcases, a shadowy looking guy with sharp features glanced at me and whispered (in English): “Why are you here?” Flummoxed at first, I didn’t know what to say. “I’m flying onward to Afghanistan,” I said. Later, I realized he was probably an agent with Pakistan’s secret police, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). My answer seemed to satisfy him as he vanished without a trace.

Rather than spend time exploring Islamabad on foot, I decided to ride out the wait for the UN flight back at my hotel, the city’s five-star Marriott. Ordinarily, the U.S. government would never allow us to stay at such an expensive place, but the Marriott was the only hotel in town that met the State Department’s stringent security requirements. I wasn’t going to complain. The irony of that Afghan reporting trip was that it began in the absolute lap of luxury. By day, I lounged around the Marriott’s secluded pool; in the evenings, I could choose from any one of half a dozen restaurants for dinner.

Tragically, the Marriott didn’t prove to be as impervious to attack as the State Department believed. Six years after my stay, in 2008, the Marriott was leveled in a massive truck-bombing perpetrated by a wing of al-Qaeda. The attack killed more than 50 people and wounded nearly 300 others. On first hearing news of the bombing, my thoughts went to the hotel staff -- the waiters, reception clerks and doormen who had been so kind to me during my stay. One of my first dinners at the Marriott had been at a restaurant that featured an extravagant buffet. As I ate my meal, one of the waiters, an older gentlemen with well-worn smile marks around his eyes, approached my table and asked which of the buffet dishes I liked best. Wanting to be polite, I complimented the restaurant on the roast beef and seafood but told him that my favorite dish was actually “dal,” cooked lentils and sauce. The waiter laughed as if he’d never heard anything so ridiculous: “Mr Baker,” he said, “that’s the simplest dish in all of Pakistan.” I certainly hope he got out of that horrific attack unharmed.

I had never reported on that part of the world before and I had a lot to learn. I can still recall my surprise on the UN flight over from Islamabad to Kabul. It had been a beautiful, sunny day and my mind wandered as I gazed out of the airplane window over the city of Peshawar below and beyond to the barren range of mountains that separates Pakistan from Afghanistan. As the plane approached Kabul, all of the female passengers -- mainly Western aid workers, UN officials, journalists and government workers – onboard, one by one, methodically reached into their purses and pulled out scarves to tie around their heads. By the time we touched down in Kabul, every female head on the plane was covered.

Despite the fact that Afghanistan, at the time, had essentially been at war for decades and had just a few months earlier emerged from another period of heavy fighting, the mood in Kabul couldn’t have been more different than in Pakistan. People seemed genuinely friendly and outgoing in a way that I hadn’t sensed during my stopover in Islamabad. Taliban rule had been especially brutal and most people seemed all too happy to see their cheerless leaders go. The welcome felt especially warm for Americans. Maybe it was my own skewed perception of danger, but I never once felt personally threatened during my stay.

The few weeks I spent in Afghanistan were some of the most productive and satisfying of my entire journalism career. The initial expectation from my boss back in Prague was that I would file a four-minute radio feature every day. I was intimidated at first by the expected workload (a four-minute feature might sound insignificant, but it’s actually not easy to report, write and record a full-length feature every day). I needn’t have worried too much. There were simply so many stories to cover and they practically all wrote themselves.

As I was writing this post, I searched the net and found some of my old stories (many thanks to the staff at RFE/RL who maintain the archives). To give you an idea, here’s a link to a feature I wrote on efforts to restore Kabul’s fabled Babur Garden park and another on attempts by Afghan filmmakers to rebuild the film industry. It’s a rare sensation for a journalist to feel that he or she, through their stories, is helping a country, but it was precisely that feeling that propelled me out of bed every morning.

On one of the days, I and my local Afghan translator, Mustafa Sarwar, traveled to the particularly devastated western side of Kabul to interview teachers and students at a school for girls that had recently re-opened. The students were too shy to speak to me on mic, but I still remember them giggling and laughing at our presence (and my old middle school anxieties coming back). On another day, Mustafa’s uncle, my official driver, drove us up to the Panjshir Valley, about 100 miles north of Kabul, where during the 1980s, the legendary Afghan commander Ahmad Shah Massoud had successfully repelled Soviet tank incursions. During that trip, the local Afghans proudly lined the road and pointed to the rusting Russian tanks still lodged in the valley’s impassable crevices.

When we weren’t reporting stories, Mustafa and I would explore Kabul’s evocative central market or hang out on Chicken Street, a ramshackle lane filled with junk shops, carpet dealers and tiny food shops that would occasionally sell cans of beer from below the counter (provided there was no else in the store to witness the transaction). I once paid $7 a can for Russian "Baltika" beer to bring to a party thrown by the local chapter of the international aid group, Médecins Sans Frontières. I didn’t want to show up to the bash empty-handed.

Mustafa and I would also occasionally head over to the massive NATO air base at Bagram, north of Kabul, to hunt for news stories or attend military briefings. One of those trips to Bagram, though, had nothing to do with reporting – and to this day, I look back on that outing as a sign that some benevolent force was watching over us the entire time.

Mustafa, on that particular day, had shown up for work with a terrible toothache. The Taliban weren’t exactly known for skilled dentistry, and Mustafa’s teeth were in bad shape. I wanted to help if I could, so I asked around if there might be a Western dentist in town who could take a look. As it turns out, the best dentist in Kabul at the time was a Czech doctor stationed at Bagram. I figured with a few words of Czech I might be able to talk our way past the guards, and we promptly set out on the hour-long trip to the base. At first, it didn’t look promising. The guards were firm that on-base dentists weren’t permitted to treat Afghan civilians. And then our luck changed. One of the Czech soldiers on duty had been assigned, months earlier, to guard RFE/RL’s headquarters in Prague from a possible terrorist attack. Incredibly, he recognized me from those many mornings when I would pass through the lineup of tanks that circled our building, and he came over to say hello. He turned out to be a great guy. After I explained why we were there, he sneaked us in through the barriers. Within an hour, Mustafa was splayed out in the chair as an affable Czech dentist bent over his mouth and examined his teeth.

After I returned to Prague and settled back into my routine, I slowly put Afghanistan on the back burner. The Iraq war came not long afterward, and that conflict, for years to come, would gobble up the headlines that might have gone to a place like Afghanistan. Like most people, I suppose, I assumed the Afghan war had largely been won. And while the occasional reports of fierce fighting in places like Helmand and Kandahar provinces were alarming, I figured the U.S. and NATO troops were simply mopping up insurgent violence and that eventually everything would somehow work itself out.

The decision to invade Iraq was tragic on many counts, and still stands as the worst American foreign policy blunder since at least the Vietnam War. Looking back, though, I think it’s clear that the ill-fated effort to topple Saddam Hussein helped to seal Afghanistan’s fate as well. Re-reading some of my old stories from Kabul, I found this nugget: Kabul Fears Iraq War Could Divert International Attention From Its Struggle. The story, dated September 23, 2002, starts out with this paragraph:

“In the Afghan capital, Kabul, there's a growing feeling of 'deja vu' as talk in the United States and Europe turns increasingly to war against Iraq. Many here draw similarities to 1992, when Afghanistan emerged from one war only to fall into another, while the West fixated on problems in Yugoslavia and other areas. The fear is that, once again, the international community will turn away at a crucial moment in Afghanistan's history.”

I certainly wasn’t the only journalist who wrote that story at the time; many others had also foreseen the potential dangers of the U.S. and its allies losing focus on Afghanistan as attention shifted to another conflict.

It's beyond the scope of this post to answer where the Afghan engagement went wrong – particularly after it started out so promisingly. The rampant corruption in the Afghan government would have always been a problem, and as the world saw this past summer, the Taliban had no intention of ever going away. I still wonder, though, how much could have been accomplished – might yet still be accomplished – if the U.S. and its allies had firmly grasped the transformative opportunities that they (we) had in the early days of the war.

(Scroll past the map for more photos.)