Modern-day visitors to the Black Sea port of Constanța might be confused by the city’s enthusiastic embrace of the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17 AD). There’s a big statue of him in the center of the old town, standing on a square called, appropriately enough, Ovid Square (Piața Ovidiu).

After all, Rome is more than 2000 km (1200 miles) away by land (though arguably easier to get to by water). Maybe Romanians just have a thing for Latin poetry?

The fact is Ovid actually did live here a little more than 2000 years ago. He was banished to Constanța, then called “Tomis,” by Emperor Augustus in 8 AD not long after his 50th birthday for reasons that remain unclear to this day. Ovid was no shrinking violet when it came to expressing himself, even in exile. He wrote reams of letters and poems to his friends and allies back home in Rome, but he never did reveal his great crime, saying only he’d been banished for a “poem and a mistake.”

Ovid’s puzzling banishment has unleashed, over the ages, one of the great mysteries of Roman scholarship in trying to figure out exactly what his crime was. Maybe it was a poem he wrote about adultery (then, like now, a taboo that’s both frowned upon and relatively common)? Or perhaps he got caught up in a conspiracy to murder the emperor? Could it be that Augustus simply didn’t like his poems? Scholars can’t agree and we’ll likely never know.

What’s not a mystery, though, is that Ovid really didn’t like Tomis. If modern-day Constanța is head-over-heels smitten with the poet, it’s safe to say this was definitely a case of unrequited love.

Here, in Ovid's own words, was how he described Tomis:

"I’m here, abandoned, on the furthest shores of the world, where the buried earth carries perpetual snowfall. No fields bear fruit, or sweet grapes, here, no willows green the banks, no oaks the hills. Nor can you celebrate the sea rather than the land, the sunless waters ever heaving with the winds’ madness ...

Wherever you look are uncultivated levels, and the vast plains that no one owns. A dreadful enemy’s near to left and right, terrifying us on all sides with fear of our neighbors. One side expects to feel the Bistonian spears, the other arrows from Sarmatian hands."

This was the harsh reality of everyday life in Tomis as described by Ovid in a letter to the Roman Senator Gaius Vibius Rufinus. Rufinus was an acquaintance of Ovid’s and presumably someone who might sympathize with the poet’s situation. (For this translation and others, I’m indebted to the work of A.S. Kline and the amazing website Poetry in Translation.)

Romanians, these days, poke fun at their scruffy Black Sea port city and there are certainly a lot of things to criticize, but it’s fair to say Constanța has come a long way from its Tomis days.

At the time of Ovid’s ostracism, Tomis sat at the far-eastern end of the then-expanding Roman Empire. Just as BC turned into AD, Roman ships were cruising through the Black Sea in search of new territories to conquer. The Romans proceeded to colonize a string of ancient Greek ports that lined the sea on all sides, though it would be many decades (and even centuries) before Rome’s full cultural influence would be felt in this forgotten corner of the empire.

Kline describes the townspeople of Tomis as a mix of half-breed Greeks and barbarians related to the Dacian (or Thracian) tribes that once covered much of the area of modern-day Romania and Bulgaria. He writes that the people of Tomis dressed in animal skins and wore their hair and their beards extra-long. They apparently walked around town armed to the teeth. It was a far cry from Ovid’s beloved Rome.

The threats from the Bistonians and Sarmatians that Ovid wrote about in his letters were probably real. The Bistonians were a nearby, hostile Thracian tribe. The Sarmatians were a nomadic Indo-European people known for their horsemanship and fighting ability. It’s no stretch to imagine that these warriors could ride into town one day and lay waste to what was then merely a remote Roman garrison.

The best place in town to take in all this ancient history is the city’s Museum of National History and Archeology, housed in an early-20th century building that shows off the city’s outsized ambitions a hundred years ago as the leading port for the new nation of Romania (which had come into existence only a few decades earlier). Though Constanța’s museum is not as impressive as Varna’s Archeological Museum, about 80 kms (50 miles) south along the coast, it’s strong on the two most important periods of Constanța’s classical antiquity: the Greek period during the 5th and 6th centuries BC and the early arrival of the Romans around the time that Ovid was living here.

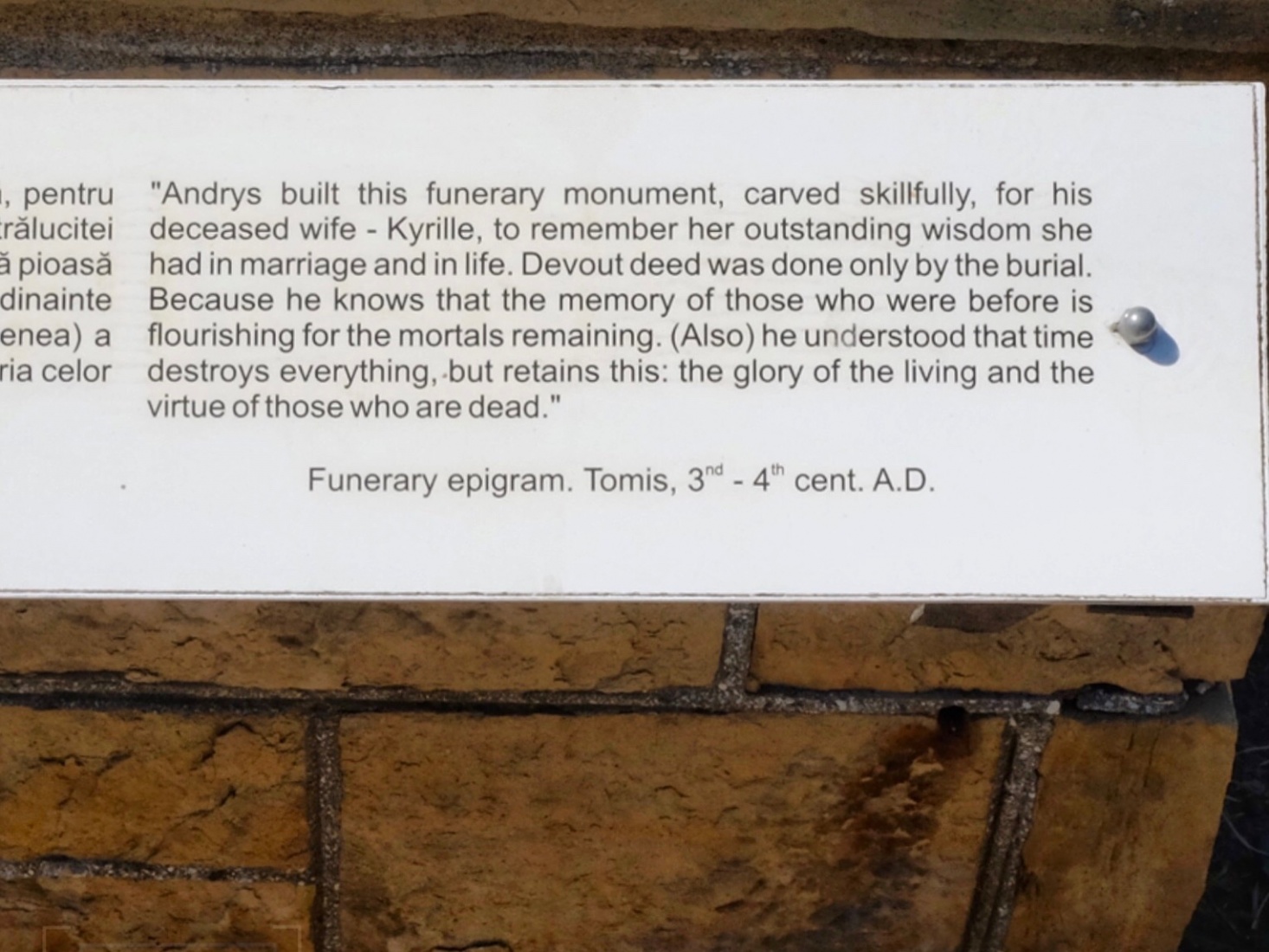

One of the museum's highlights is not actually inside, but rather a row of Roman tombstones that are lined up along the museum’s exterior. The stones are in remarkably good shape considering their age, and the epigrams have been helpfully translated into English. The words are strikingly modern in tone and highly moving. One of my favorites was written by a local man named Andrys, who buried his wife Kyrille sometime in the 3rd or 4th century AD:

“Andrys built this funerary monument, carved skillfully, for his deceased wife, Kyrille, to remember her outstanding wisdom she had in marriage and in life. Devout deed was done only by the burial because he knows that the memory of those who were before is flourishing for the mortals remaining. Also he understood that time destroys everything but retains this: the glory of the living and the virtue of those who are dead.”

History hasn't been kind to Constanța. After the disintegration of Rome around the 5th century AD, the city fell totally off the grid, at least according to the museum’s exhibits and historical information in English. The town became part of Byzantium – the eastern Roman Empire – and later the Bulgarian Empire, before finally falling to Ottoman Turkey in the late 15th century. The Ottoman Empire ruled over these parts for more than four centuries, until the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78 ultimately awarded the port and surrounding region to newly independent Romania.

Romanian independence gave the city a new lease on life. A freshly minted and rapidly growing country needed a bustling port, and Constanța quickly amassed wealth, population, and influence. The historic core is filled with the resplendent mansions and buildings built during this period – many of which today stand empty and dilapidated, awaiting new owners and new reasons to exist. The most famous of these is the former seafront casino (see photo), now a ruin, which in its early-20th-century heyday attracted royals from all around Europe.

For a port, Constanța successfully navigated Romania’s tortured path through both of the world wars of the 20th century. The city somehow survived World War II intact – a war that saw the country dramatically shift its allegiance from Nazi Germany at the start of the conflict to the allies in 1944. Both the Russians and Germans, at various times, had plans to reduce the city to rubble, but neither thankfully carried through on their threat.

Constanța even, for a time, played an elevated role in helping spare at least part of Europe’s Jewish community from Nazi (and Romanian) annihilation. From 1938 to 1941, many passenger ships left here and safely ferried Jews through the Black Sea to Istanbul and ultimately to Palestine. These refugee ferries came to a tragic end in 1942 with the sinking of the “Struma,” just north of Istanbul, by a Soviet submarine in February of that year. The boat had left from Constanța but had gotten delayed in Istanbul after British officials governing Palestine said passengers would not be allowed to enter. Nearly 800 Jewish refugees died in the sinking, making it one of the biggest civilian maritime disasters of the war.

Constanța, a melting pot of cultures over the centuries, from Greeks and Romans to Turks, Bulgarians and Romanians, once had its own sizable Jewish population of about two thousand before the start of World War II. Most of these people died in the Holocaust (and a handful successfully emigrated), though the city does have one surviving synagogue to attest to their memory.

The problem is that like much of the rest of the city, the synagogue is little more than a shell of its former self. On this most-recent visit, I noticed that the building’s roof had almost completely caved in and a few feral dogs were lounging in the garden. The sight would have given Ovid one more reason to weep.

Thank you. Romania is a mystery to me and I quite enjoyed learning of its Roman history and the story of Ovid’s exile. Your photos gave me a real sense of the town, a kind of “land that time forgot.” The last one, with the old car, might have been somewhere in Cuba…..

Thank you. Romania is a mystery to me and I quite enjoyed learning about its Roman history and the story of Ovid’s exile. Your photos give a real feel of the town, a kind of “land that time forgot.” The last one, with the old car, might have been taken somewhere in Cuba….

Thank you, Penny, for reading and leaving such a thoughtful comment.