From Litoměřice, we retraced our steps back toward Prague and plunged into southern Bohemia, with its towns and castles. We couldn’t wait to visit the 15th-century Hussite (Protestant) stronghold at the city of Tábor, whose early history as a haven for anti-Catholic rebels during the religious wars of the 15th century was unique among Czech towns. We read up on the exploits of the legendary Hussite military commander, Jan Žižka, but found the stories of the competing Christian sects that flourished here, like the Bohemian “Adamites,” to be even more compelling.

The Adamites apparently ran around without wearing any clothes and practiced public fornication (among other eyebrow-raising rituals). We quickly realized it wouldn’t be hard to entertain Fodor’s readers with stories like these. The reality of modern Tábor, a dusty industrial town with a pretty main square and an elaborate network of dark, underground tunnels, was slightly underwhelming (and it was far too cold to walk around naked), but the idea of a place that was established expressly to serve the principles of the early Christians had been fascinating.

Another town that captured our imagination was Český Krumlov, which we found to be nearly empty on a snowy, mid-February night as we eased our car along the narrow, cobblestoned lanes to our hotel on the main square. Delia was obsessed with the Austrian painter Egon Schiele, whose mother, Marie Soukupová, was born in Český Krumlov in 1862.

Schiele used the magnificent old town as the model for his cycle of paintings, “The Dead City” (Die Tote Stadt). That first evening, we combed Krumlov’s back alleyways and looked out across the river at the darkened Renaissance castle. With its hundreds of empty windows, the castle complex certainly looked “dead.” It was apparent, even then, though, that pretty Krumlov wouldn’t remain obscure for very long (though no one could have foreseen just how incredibly popular the small place would eventually become). Maybe the two of us were partly to blame. This is how we described it in the book: “None of the surrounding towns or villages, with their open squares and mixtures of old and modern buildings, will prepare you for the beauty of Český Krumlov. Here, the Vltava works its wonders as nowhere else but in Prague itself, swirling in a nearly complete circle around the town.”

Bohemian Castles & Spas

From southern Bohemia, we drove slowly north and west toward the famous spa towns of Karlovy Vary (Karlsbad), Mariánské Lázně (Marienbad) and Františkovy Lázně (Franzensbad). The resorts, situated at Czechoslovakia’s far-western tip, where Bohemia meets Bavaria, once attracted luminaries like Goethe, Chopin, Nietzsche, Karl Marx and even the American writer, Mark Twain. They came to admire the architecture, stroll the wooded paths and sip the health-giving waters that bubbled up through the ground from the hot springs below. In more recent years, under the communists, the resorts had been converted to fancy-looking convalescent centers – in effect, state-run hospitals – where industrial workers could go to seek relief from modern-day maladies, like hypertension and poor digestion.

As with Český Krumlov a couple nights earlier, the streets of Karlovy Vary were deathly quiet as we pulled the car into a small lot in front of our hotel, the plain-looking “Interhotel Central.” We couldn’t quite justify the expense of one of the spa’s more-glamorous hotels, such as the upscale “Dvořák,” which had just reopened under new Austrian management, or the opulent, 19th-century “Grandhotel Moskva-Pupp,” which was just then in the process of scrubbing the “Moskva” (Moscow) part from its name. The communists had added “Moscow” as a way of making this big, bourgeois palace somehow more palatable to the proletariat; the hotel’s new owners couldn’t wait to strip it away.

After checking in at the Central, we strolled the resort’s empty, snow-covered streets and marveled at the brilliantly lit, palatial buildings surrounding us on all sides and twinkling out from the hillsides on the horizon. Lured on by those lights, we hiked out of the main spa area, into the hills and toward the mighty-looking, neo-Renaissance “Imperial” spa. The building was aglow, and from a distance we must have imagined that some great party or celebration was underway. Only as we approached the magnificent structure did we realize that nothing much was happening at all. The Imperial, at the time, was just another one of those glorified hospitals, and half-empty at that. The lights were merely a mirage.

In the years since the Velvet Revolution, Karlovy Vary and its sister resorts have struggled to reclaim their lost luster, but with only mixed results. The grand architecture, breathtaking settings and night-time lights are all undeniably beautiful, yet they conspire to create the illusion of activity when in fact these places (outside of events like Karlovy Vary’s international film festival) are often lifeless.

Delia and I spent the next day ambling around Karlovy Vary’s main spa zone, along both sides of the town’s smoldering Teplá River, and admiring the impressive neo-Renaissance Mill Colonnade and the intricately carved Market Colonnade, where visitors would congregate to drink the waters. We recognized the latter as the work of the Viennese architectural duo, “Fellner & Helmer,” which through their many neoclassical buildings (including Brno’s Mahen Theater and the Prague State Opera) in the late-19th and early-20th centuries did more to mark out the old Habsburg Empire than perhaps even Emperor Franz Joseph himself. As impressive as those older colonnades were, though, it was the more-modern, Brutalist-looking “Yuri Gagarin” colonnade, in the center of the spa zone, that captured our attention. Dozens of people packed themselves inside the glass and concrete structure. They promenaded somnambulistically up and down, eyes glazed over, as they clutched their porcelain drinking spouts and inhaled the spray from a roaring geyser inside. I had never seen anything like it before. Delia and I purchased our own drinking cups, joined in the fun, and promptly came down – as many people do after their first few enthusiastic gulps of the water – with the runs.

From Karlovy Vary, we took day trips to nearby Mariánské Lázně and Františkovy Lázně. In mid-February, both felt badly depopulated, but Mariánské Lázně’s spacious, wooded setting appeared more suited than built-up Karlovy Vary to how I had imagined a real spa might look. I was especially taken with the enormous “Weimar” hotel – incongruously called the “Kavkaz” (Caucasus) on our visit, as if it stood somewhere on the banks of the Caspian Sea. The grand Empire-style edifice, at least as big as a city block, had been a favorite of England’s King Edward VII at the turn of the 20th century. On our visit, the hotel was struggling to attract guests. On a more recent trip to Mariánské Lázně, in 2020, I noticed the hotel had sadly closed and stood abandoned. Tiny Františkovy Lázně was even quieter, though we appreciated the soothing yellow façades of the town’s main buildings. We chalked up the all-pervasive feeling of calm to a lack of any stimulus in the place whatsoever.

Crossing the ‘Border’ into Slovakia

From Western Bohemia, Delia and I began a several-hour drive east across Bohemia, onward through Moravia and finally to Slovakia, back then of course a constituent piece of Czechoslovakia. As we threaded the hills of Moravia’s low-lying Beskydy range and sailed across the Slovak border (merely a road sign marking the provincial division), we scarcely spared a thought for the fact we might be entering a different country. While debate over Slovak independence had already begun to heat up, Czechoslovakia’s breakup, to us at least, still seemed unimaginable.

We put in that first night at the Slovak city of Poprad, at the base of the mountains, though the town, with its rows of dilapidated public-housing projects, interspersed with factories and power plants, proved to be a disappointment. Only the next day, after we began our ascent, did we recognize the full majesty of this compact range. The rocky peaks emerged suddenly as if they had been plunked down in the middle of a field. The High Tatras are truly a natural wonder, among the smallest in area of the sprawling Carpathian chain, yet stuffed with its highest peaks, some approaching 9000ft.

We drove up first through Starý Smokovec, the most central of the mountain’s three main resort towns, and then diverted eastward toward Tatranská Lomnica, where we had booked our hotel. When we eventually rolled up to the haunted-looking, fin-de-siècle, Alpine-baroque “Grandhotel Praha,” we knew we’d found something special. The hotel dated from 1905 and was originally built by the Wagons Lits-Cook travel company. Its worn interiors, frayed carpets and chipped plasterwork – the effects of years of neglect – couldn’t hide the structure’s lustrous ballrooms, balustrades and chandeliers. From that point on, I’ve only ever been able to see the High Tatras through a pair of sepia-toned goggles, like something out of Wes Anderson’s “Grand Budapest Hotel.” Delia and I spent the next couple of days riding the lifts and hiking the well-marked trails around the tops at a line just above the pine trees.

That trip sparked a love affair for me with the High Tatras that has lasted to the present day. Indeed, I still remember my first thought once news of Czechoslovakia’s dissolution, on January 1, 1993, began to fully sink in. It wasn’t that I would no longer see Slovakia’s signature halušky dish quite as often on Prague menus or hear the softer Slovak language spoken as frequently on the city’s streets. My first thought was that the High Tatras would no longer be part of the country I was then living in. I understand both sides of Czechoslovakia’s divorce debate (and I won’t get into the arguments here), but that realization struck me at the time as a highly regrettable loss.

Relics of the Old Regime in Košice

As we pressed eastward from the High Tatras, the historic Slovak towns of Kežmarok, Levoča and Bardejovské Kúpele offered pretty central cores, but were clearly not yet as prosperous as their more-westerly counterparts in Bohemia and Moravia. The breathtaking vistas of low-lying mountains and broad, faded-green valleys were occasionally interspersed here and there with harsher glimpses of impoverished-looking, roadside Roma (gypsy) settlements. The further east we drove, the fainter the political echoes of the Velvet Revolution protests resounded. It would clearly take time before the repercussions of the changes were felt all the way out here.

From the town of Bardejov, we diverted northward toward the Polish border to visit the region’s historic wooden churches and take a look at the fabled World War II-era Dukla Pass. It was here, in late 1944, where the Soviet Red Army, along with detachments of Czech and Slovak resistance fighters, first breached the German lines and launched the liberation of Czechoslovakia. The pass’s lonely bunkers, trenches and watchtowers still stood as if the battle had taken place only months earlier. A giant, red-starred memorial, standing in an empty field, underscored the immense propaganda value the communists still attached to the battle.

We felt the strong, lingering presence of the old regime as well in the nearby city of Prešov, where officials still highlighted that city’s odd connection to Bolshevik Russia and the founding, in 1919, of the first “Slovak Soviet Republic (SSR).” That ill-fated venture, an extension of revolutionary Béla Kun’s Hungarian Soviet Republic, lasted just a few short weeks. As Delia and I strolled Prešov’s night-time streets, though, we were shocked to see the wrought-iron balcony on the town’s main boulevard, from where the SSR was first proclaimed, still strangely bathed in ceremonious lighting.

Our arrival in Košice, the capital of eastern Slovakia, marked the culmination of our month-long quest. We walked the city’s oversized main square and gazed at the grand, Gothic St. Elizabeth Cathedral and the nearby medieval town walls that had served the Hungarian nobility so well over the centuries in their battles against the Ottoman Turks. Once again, though, we noticed plenty of odd, outdated references to Marxism, especially at the city’s museums. The political changes in 1989 had caught museum curators off-guard all around the country as they scurried to reorganize exhibitions and rewrite the accompanying descriptions to reflect the new political realities.

Nowhere, though, did curators appear to have more work to do than in Košice. As we climbed the town’s landmark, 16th-century “St. Urban Tower” to view a dry exhibition on medieval bell-making, we laughed out loud on reading that the ironmongers continued to “forge the revolutionary conscience of the workers” into the modern day by creating the metal statues that graced the city’s high-rise public-housing complexes. I haven’t been back to that tower in many years. Perhaps the description is still there.

From here, Delia and I began the long drive back to Vienna. After briefly stopping over at a few places in between, we arrived home in early March, energized and exhausted from what had been an amazing journey. I can’t remember now the total number of miles we racked up on the odometer, but we covered a significant chunk of the distance from one coast of the United States to the other. Even with that effort, we never made it to Bratislava; instead, we researched the Slovak capital on a series of day trips from Vienna after we got back. A big part of the project was now finished, but a bigger big part – actually writing the book – still lay ahead.

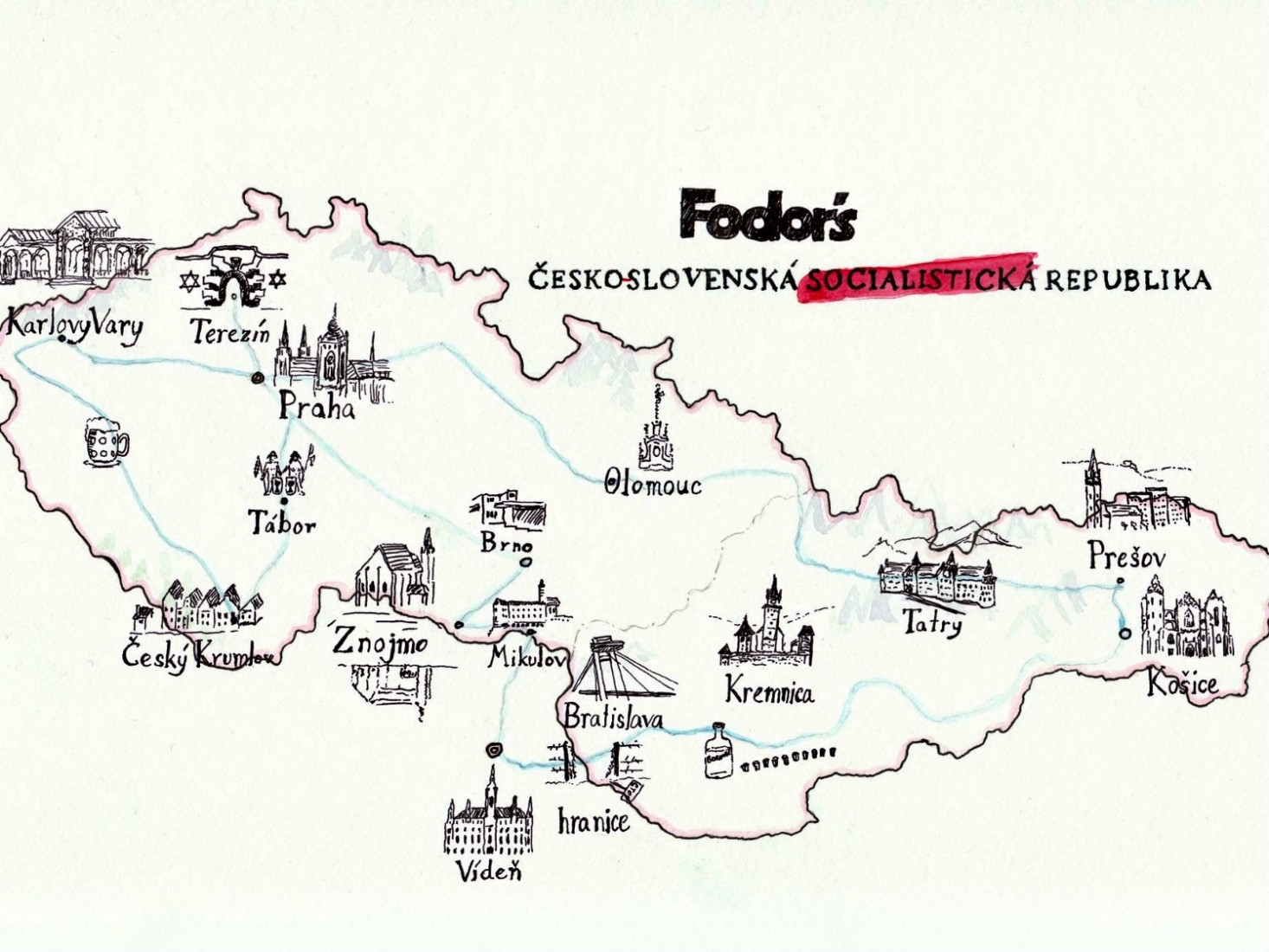

(Scroll past the map to see some screenshots on Slovakia from the book.)

*Rough Guides also published a travel guide on Czechoslovakia around the same time.

Did you like the story and want to add your own experiences? Or maybe help me to correct something I didn’t get right? Write me at bakermark@fastmail.fm.