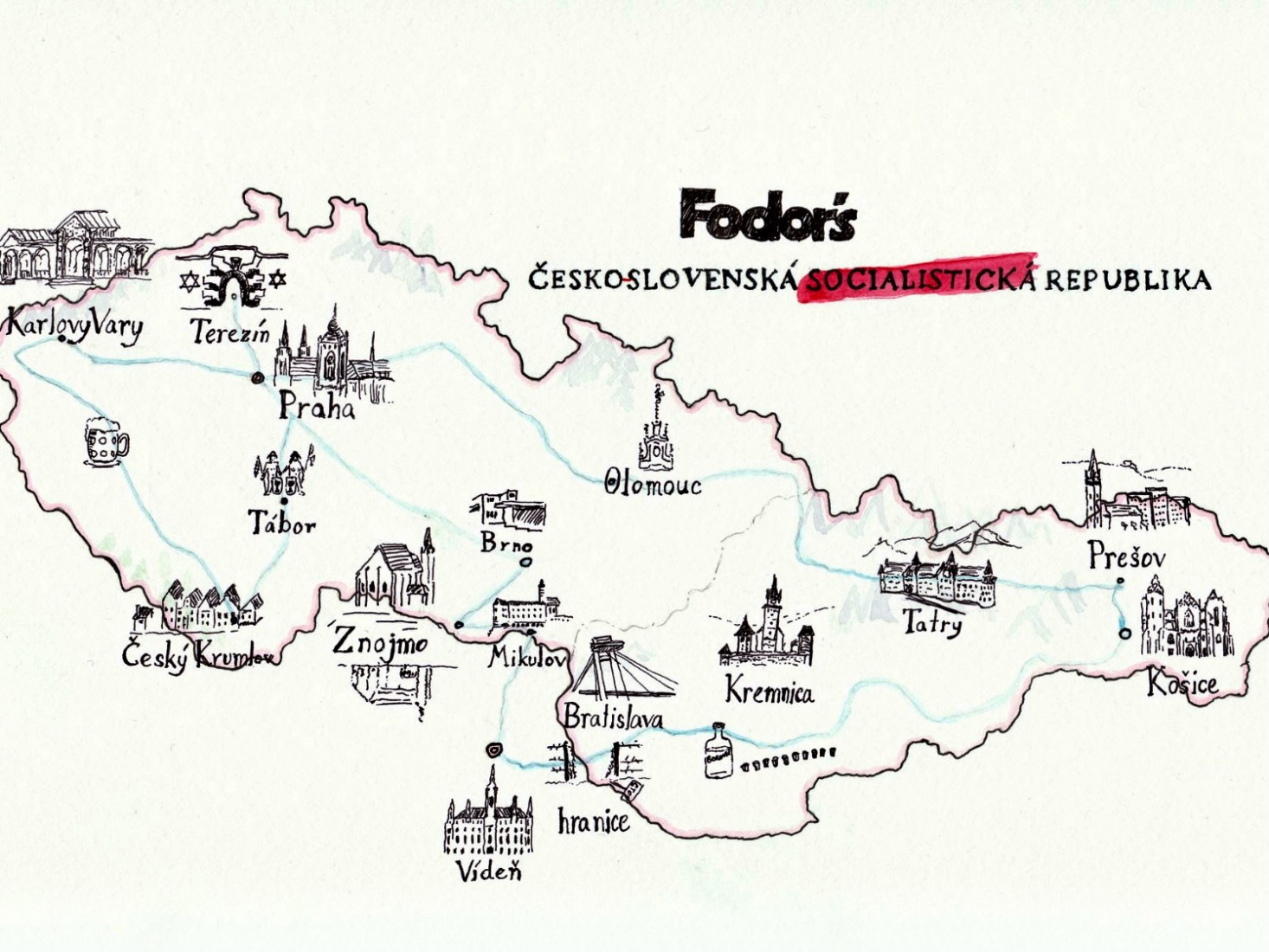

Prague was the one city in Czechoslovakia that both Delia and I knew relatively well. I had traveled to the capital regularly for four years as a reporter for the newsletter “Business Eastern Europe.” Indeed, the frequency of my trips to the city had raised suspicions among the country’s communist-era secret police, the StB, who started to think I was more than just a diligent journalist. I later discovered they had spent hundreds -- if not thousands -- of man-hours following me and recording my visits to figure out if I might also be a spy. I wrote about their covert surveillance operation in an earlier post (that you really need to read), but that’s a whole different story.

The drive Delia and I took up from Brno to Prague in February 1991 for our Fodor’s trip had come nearly a year to the day since my last journey to the city, in February 1990, to cover an economic conference. That 1990 trip had followed by just a couple of months the jubilant, anti-communist Velvet Revolution, and the city was still buzzing with excitement.

This time around the mood had shifted, but it was hard to pinpoint exactly how. Many of the uplifting "Havel na hrad!" (Havel to the castle!) signs demanding the restoration of democratic rule and for prominent dissident Václav Havel to become Czechoslovakia’s new president had disappeared from the city’s streets, though shop windows still proudly displayed Havel’s portrait. His earlier, scruffier dissident look in the older photos, though, had been replaced by a newer image showing him dressed smartly in suit and tie and looking decidedly more “presidential.”

Just as with Havel’s own evolution, some of Prague’s own scruffy, dissident feel had begun to wane. That collective aura of optimism of a year ago – that happy belief anything was possible – had morphed into something more focused and tangible: the recognition the future was now and there was money to be made.

Ham Rolls Stuffed With Whipped Cream

By early 1991 it was already obvious that Prague – with its picturesque riverside setting and historic Gothic and baroque architecture – would become a major tourist draw, and residents were scrambling to carve out a piece of the action for themselves. Locals swarmed the platforms of arriving international trains in order to offer travelers private rooms in their apartments for as little as $10 a night (travelers were often surprised to discover those rooms were located in distant public-housing projects, miles away from the central attractions).

The number of new, privately owned companies offering accommodation services, guided tours and souvenirs had exploded. Since I had already visited Prague several times in the past and was familiar with the main sights, like the Old Town Hall and Prague Castle, Delia and I spent much of our time tracking down these companies to see whether their tours and souvenirs were worth mentioning in our book.

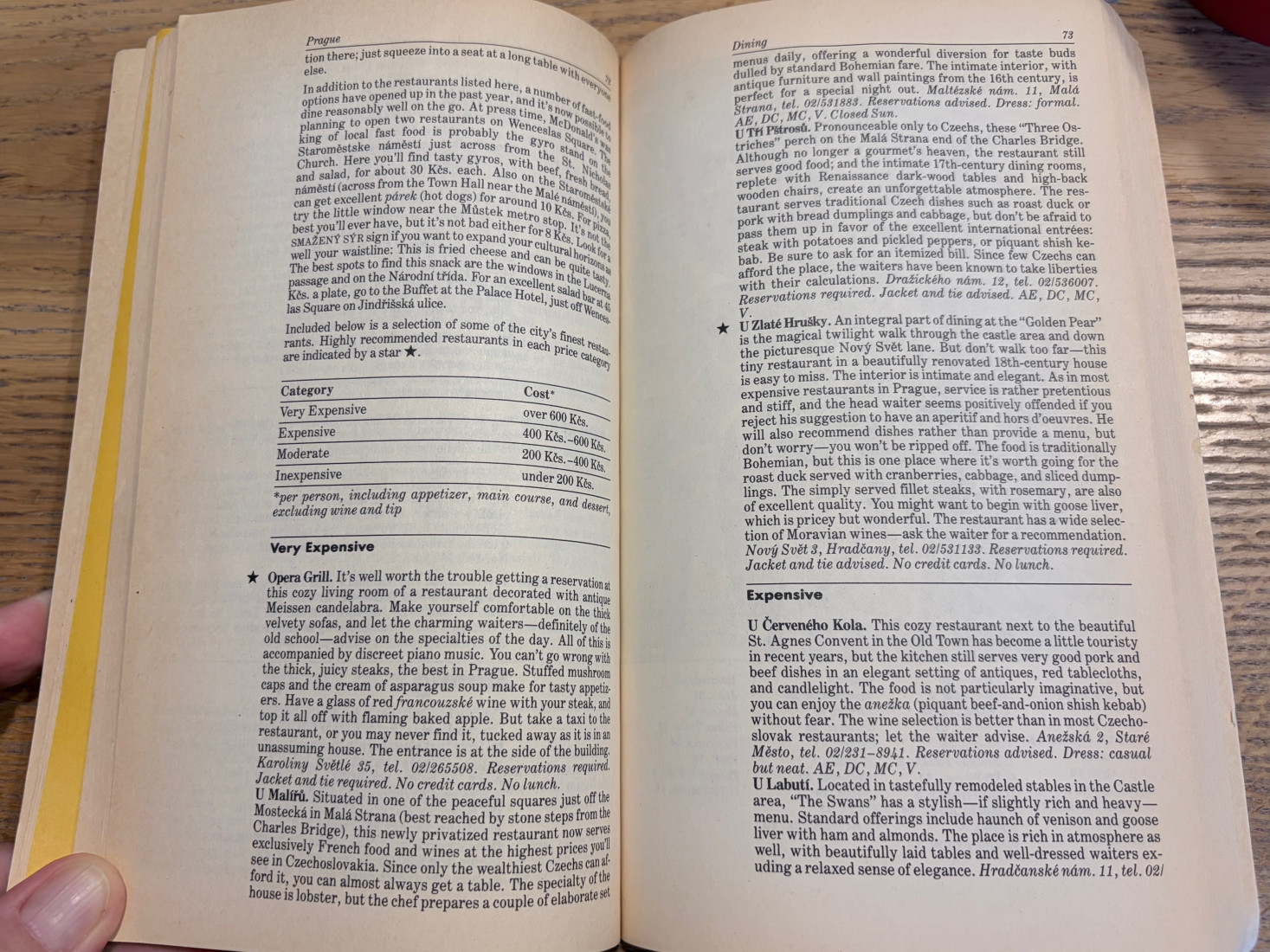

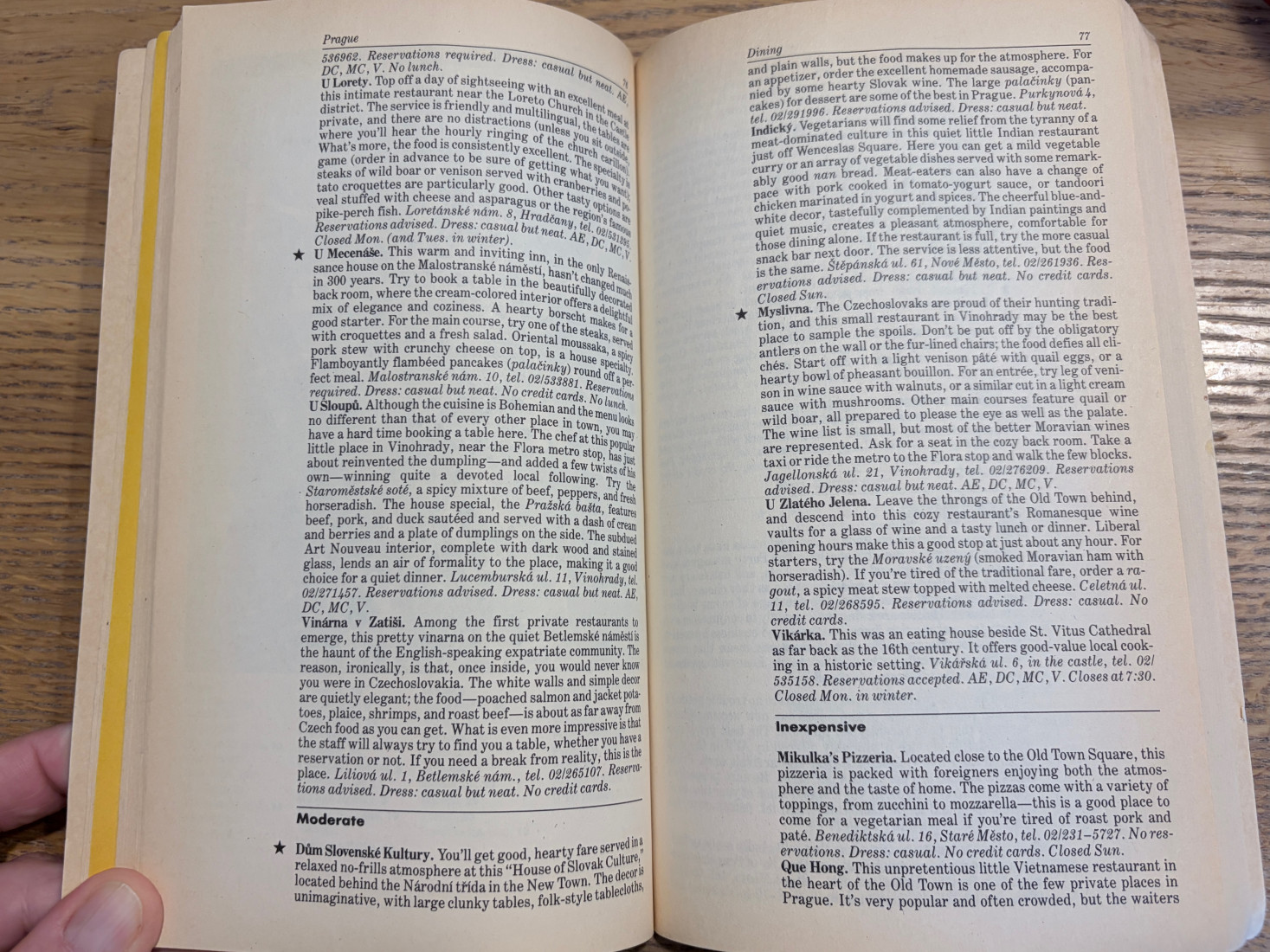

In spite of this surge in new businesses, Prague's dining scene hadn’t yet changed much from communist times. With the privatization process still in its infancy, city residents likely lacked the opportunity or know-how to run their own restaurants. Thumbing through our Fodor’s guide now, I see many of our recommendations were communist-era holdovers from the 1980s, with elegant-sounding names like “At The Golden Pear” (U zlaté hrušky) or “At The Golden Deer” (U zlatého jelena).

Despite those promising names, the restaurants themselves were all broadly the same – and mostly mediocre. A dinner would normally start with an overpriced shot of a Czechoslovak-made herbal bitter called Becherovka, followed by an appetizer -- often ham rolls stuff with horse-radish-flavored whipped cream -- plucked from a tired-looking cart that had been wheeled over to the table.

We wrote more enthusiastically about the burgeoning street-food scene. The offerings now included pizza topped with ketchup, greasy plates of fried cheese, and waffles covered in a synthetic-looking whipped cream and chocolate sauce. These items were cheaper and often better than what the restaurants offered.

Sorry-Looking Lidice

After an exhausting, exhilarating few days in Prague, we drove north out of the capital to start the most difficult leg of our trip: to the former Nazi-run Jewish ghetto at Terezín, where Delia’s grandmother had spent the last two years of her life.

Before heading directly to Terezín, though, we diverted to a World War II memorial at the village of Lidice, just outside of Prague. In June 1942, German soldiers tragically and senselessly murdered Lidice’s nearly 200 men (and sent the village’s women and children to ghettos and death camps). The killings came in purported retaliation for the assassination, a couple of weeks before, of Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich by a group of Czech and Slovak paratroopers. In the aftermath of the assassination, Hitler had ordered Lidice to be razed to the ground. It didn't seem to matter that Lidice had little to do with the operation to take out Heydrich,

Our visit came on a bleak, weekday morning, so it wasn’t surprising to find the memorial nearly abandoned. What struck both of us, though, was how neglected the site looked. As we nosed our car into the memorial’s oversized, empty parking lot, we saw big clumps of weeds springing up through cracks in the pavement. The attendant on duty, clearly irritated by our presence, reluctantly flipped on the lights so that we could take a look around. The interior was barely heated.

The exhibits themselves were moving and featured brief descriptions of the victims and their fates. Shortly after the massacre, and still during the war, a group of British miners from the city of Stoke-on-Trent had founded a movement called “Lidice Shall Live” to help rebuild the village. That early blush of optimism, though, had long-ago faded. The most-recent objects on display were musty, black-and-white photos from the 1960s.

Trudging Through Terezín

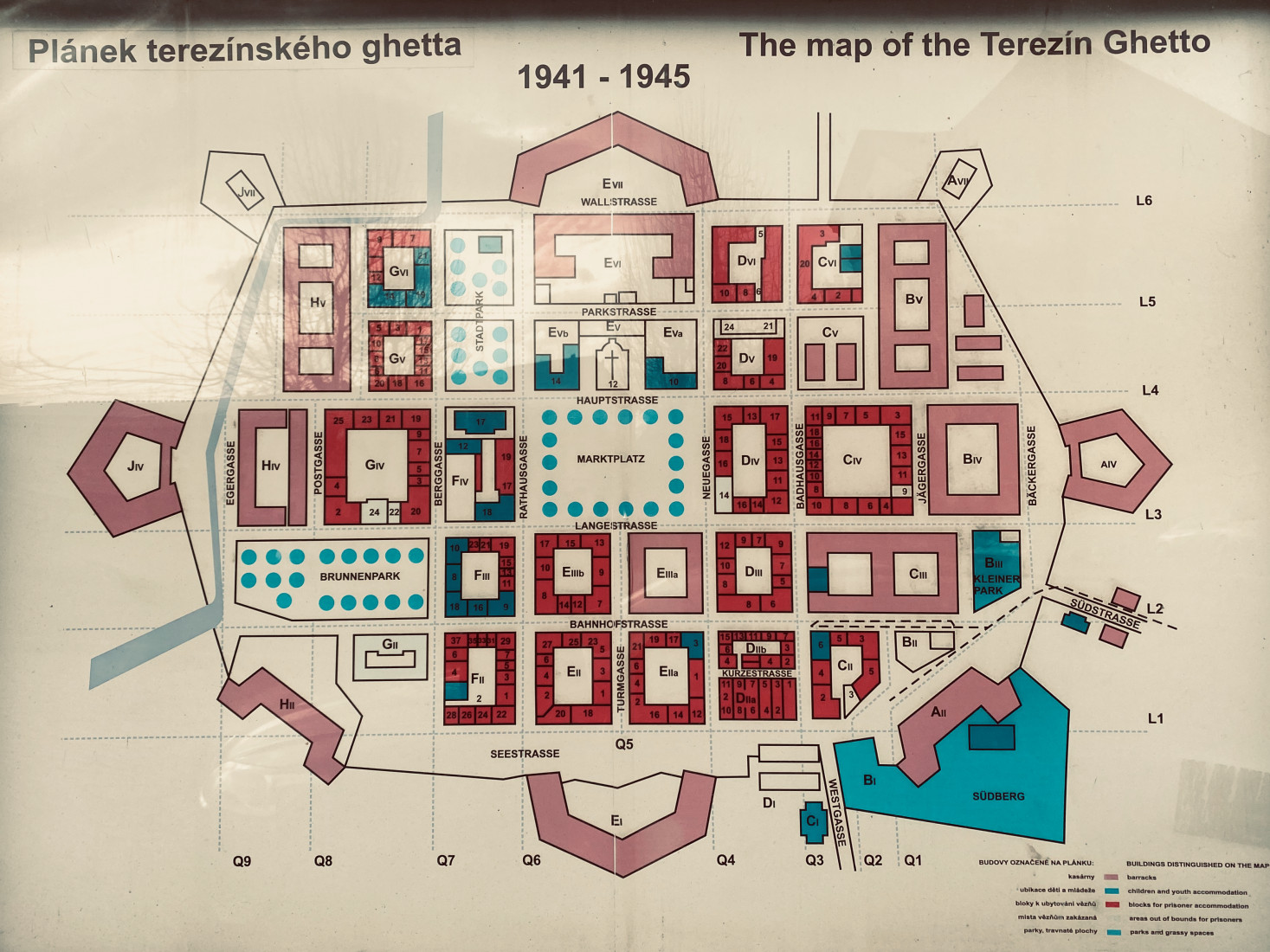

Even somber Lidice, though, couldn’t prepare us mentally for Terezín’s overwhelmingly depressing setting. Terezín had been founded originally in the 18th century to serve as an Austrian military garrison. It was cynically repurposed by the occupying Germans during World War II as the “Theresienstadt” Jewish ghetto. Theresienstadt functioned not unlike similar Nazi-run Jewish ghettos in places like Warsaw and Łódź; its main purpose was to hold prisoners before they could be transported to extermination camps and murdered. Terezín, though, had an added wrinkle: the Germans exploited the garrison’s relatively remote setting to use it as a “model” camp to prove to the international community that their policy with respect to Jews was humane.

In early-1944, the Nazis sanitized and beautified the ghetto ahead of a planned inspection, that June, by a delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The ruse worked. Following the visit, the ICRC issued a report declaring that conditions in the camp were “relatively normal.” The reality, of course, wasn’t normal at all. Of the more than 140,000 Jews who were brought to Terezín during the course of the war, around 33,000 people perished at the garrison itself and another 88,000 were eventually transported to extermination camps. The majority of these people, including Delia’s own grandmother, were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Dorothea’s transport left on October 19, 1944.

At the time of our trip, Delia knew only a handful of details about her grandmother. Before she was brought to Terezín, Dorothea had been employed as a nurse in Ulm. She was brought to Terezín originally with the understanding that the camp would function as a kind of Jewish retirement community and that she could continue her duties as a health-care worker. As part of that deception, the Nazis had given the streets in Terezín appealing, spa-like names, such as Park Street (Parkstraße), Lake Street (Seestraße) and Mountain Lane (Berggaße).

We arrived in Terezín shortly after noon and drove around the lifeless, nondescript buildings – still bathed in their chipped-and-faded Habsburg yellow – several times before finding a parking spot in front of an uninviting-looking hotel, the Parkhotel. Very little appeared to have changed in the past 50 years (to this day, Terezín still looks much as it did during World War II). My first thought was that the barren landscape resembled something out of a novel by Robert Musil, perhaps his “Confusions of Young Törless,” or any one of several other Austrian writers who spent their formative years posted to bleak military encampments like this one.

Armed with some old maps, the two of us hiked along the town’s barracks-lined streets and tried our best to imagine what life might have been like for a new German-Jewish arrival in 1942. Much as in Lidice, earlier that day, we were nearly completely alone.

Many years later, in the 2010s, Delia found and translated some of her grandmother’s old letters that she had posted from Ulm in the months preceding her transfer to Terezín and one postcard that she had sent while being held at the camp. Those documents helped Delia pin down some elusive details about her grandmother’s fate, including the date she was first brought to Terezín, August 21, 1942, and the October 1944 date she was transported to Auschwitz.

At the time, Delia had been helping her father write a book about his mother and his own experiences in the UK after arriving there on a Kindertransport train. The book, titled “The Nearly Man,” was published in 2015. In the postcard Delia’s grandmother had sent from Terezín, on September 22, 1943, she tried her best to allay any concerns about her well-being. She wrote: “I’ve been doing well the whole of my time here. I’m working as a nurse and finding lots of joy in my work. I am healthy and feel young and full of [energy]!”

In the book, Delia’s father wrote that he strongly suspected his mother was under duress when she sent the postcard, as the tone sounded very different from previous letters. Dorothea sent the card not long before the Germans initiated their beautification campaign, and they would certainly have compelled detainees, like Delia’s grandmother, to write positively about the ghetto.

The timing of Dorothea’s own transport to Auschwitz was especially tragic. It came just a week before mass transports to the death camps were halted, toward the end of October 1944. She had been part of the Nazis’ last, big push to empty the ghetto; more than 18,400 people were deported to Auschwitz in September and October that year alone.

After trudging several hours through Terezín’s lonely streets, Delia and I sized up our options for the night. We poked our noses in at the Parkhotel and asked ourselves if we could really spend a night in such a sad place. We ultimately opted to make the short drive over to the livelier city of Litoměřice and booked a room at an older hotel on the central square. The place had no running water and we had to stoke our own stove in the room for heat, yet both of us realized in that moment that we had nothing at all to complain about.

In Part 4, I finish our trip with stopovers in southern and western Bohemia, and then all the way east in Slovakia. Click here to continue reading.

*Rough Guides also published a travel guide on Czechoslovakia around the same time.

Did you like the story and want to add your own experiences? Or maybe help me to correct something I didn’t get right? Write me at bakermark@fastmail.fm.