The Internet is still a relatively recent phenomenon, and obviously people who spent the bulk of their lives before it became ever-present, as Arnold Keilberth did (born in 1929), are going to have less of a web footprint than younger people. Still, it felt odd to google Arnold’s name, as I did in 2014, and find almost nothing about him in the search results. There were no family or historical photos, no prominent citations, or web mentions; not even an obit.

It was especially odd for a person who had spent so much of his professional life working in the media. In addition to being Business International’s stringer and translator in Czechoslovakia, Arnold had worked for two giant German television networks: ARD and ZDF. His life and background seemed to have been scrubbed out of existence.

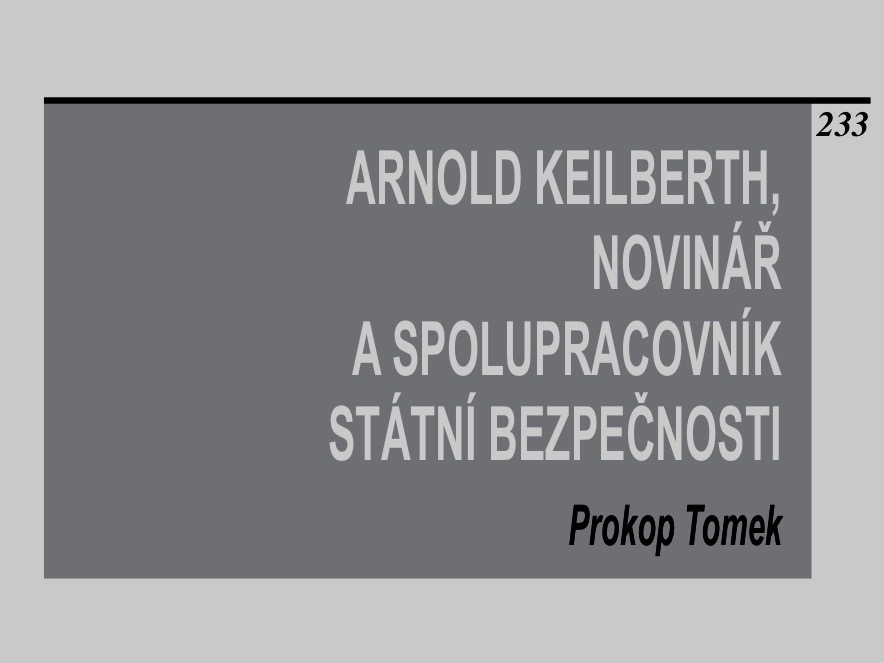

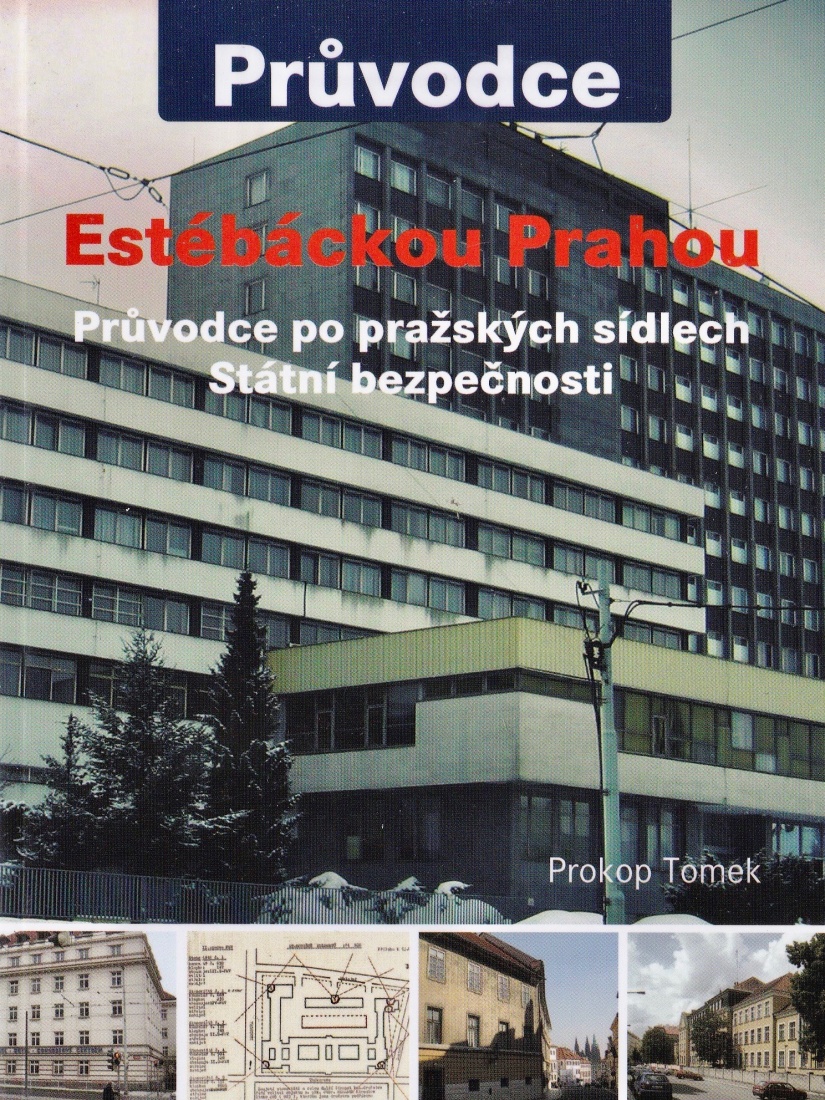

Indeed, at that time, my google search yielded only one relevant result: a link to a pdf report in Czech published in 2007 by the Czech Security Services Archive. It was ominously titled “Arnold Keilberth, novinář a spolupracovník státní bezpečnosti” (in English: “Arnold Keilberth, journalist and collaborator with the state security service.” Click on the link to download the report.)

When I read the title, my blood ran cold.

If you follow the link to download the report, you’ll see that it’s written in dense, legalistic Czech (much of it beyond my own comprehension). As I made my way slowly through the report’s nearly 20 pages, though, I was able stitch together a more complete understanding of who Arnold was (“was” is the right tense here – I learned from the report that Arnold died in 2001). He was a much more complicated figure than he’d ever let on in person, and like many Czechs of his generation he was, in turns, both a perpetrator and a victim.

I won’t speculate here about the report’s accuracy. The Security Services Archive is a highly respected academic archive. The findings are substantiated with ample citations drawn from surviving Interior Ministry documents and other contemporaneous sources. The report's author, Dr. Prokop Tomek, currently with the Prague Institute of Military History, is candid on instances where the supporting documentation is incomplete and the report, of necessity, veers into assumption. I later met with Dr. Tomek in person, and he struck me as a cautious academic, motivated primarily by finding the truth and not in settling scores with old Communists.

Some of the report’s details may not be entirely accurate, though I see no reason to doubt the document’s clear, unambiguous conclusion: Arnold – or "ARNO," one of his several code names -- was more than a passive collaborator. He was a willing, active and, at times, highly valued asset within the Czechoslovak state-security apparatus.

So what did I learn?

For starters, I had no idea Arnold’s family background was Sudeten-German (and not Czech) – though, of course, both his first and last names hint strongly at a German ethnic identity. He was born in 1929 in Czechoslovakia’s then-mainly German Sudetenland, just a few miles from the German border, in the town of Rotava. His parents were both active in the anti-Nazi Communist underground before World War II, and that probably goes a long way toward explaining Arnold’s strong and principled early devotion to Communism (at least until the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968, when his motivation becomes less clear).

Just as Nazi Germany invaded Czechoslovakia at the start of the war, in 1939, Arnold was shipped off to the United Kingdom to ride out the war years. This is where he learned his English. Indeed, in Britain, he attended both high school and college before returning to Czechoslovakia in 1947. His immersion into British life was so complete that he apparently never learned proper Czech. Dr. Tomek of the Military History Institute told me that while Arnold eventually learned to speak Czech fluently, his written Czech (at least judging from Arnold’s own written reports) remained weak throughout his life.

Day-to-day life as an ethnic German was no cup of tea in Czechoslovakia in 1947. Millions of Sudeten Germans were expelled to Germany in the aftermath of the war, owing to a suspected wartime allegiance to Adolf Hitler (or simply because they were Germans). The report states, though, that Arnold was able to stay in Czechoslovakia thanks to his father's prewar activities and own his residence in the U.K. I can imagine, however, it might have felt awkward being “home” during this period and that, at least in the early years, Arnold might not have been entirely comfortable in Czechoslovakia.

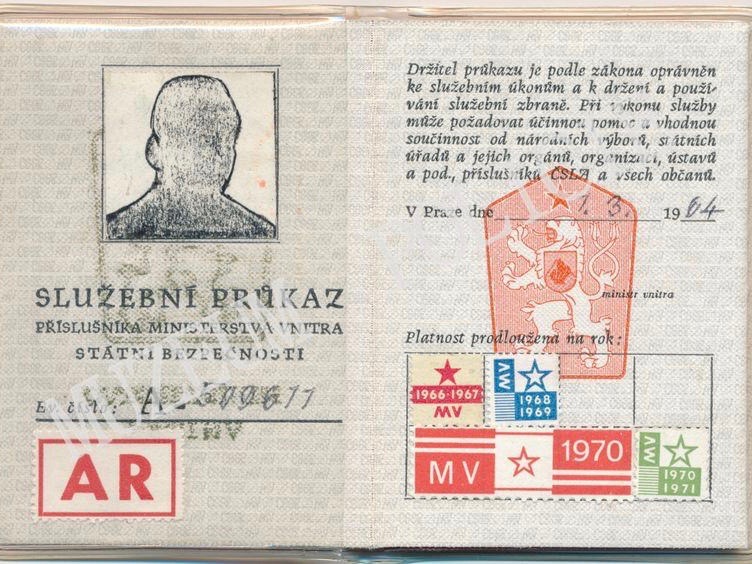

After presumably attending a crash course in Czech language, Arnold rose slowly through the ranks in the 1950s and ‘60s, taking factory jobs and working closely with the trade unions (which became his area of expertise). He joined the Communist Party as a full member in 1958, and this -- coupled with his fluency in both German and English -- made him a natural recruitment target for the State Security Services (referred to here generically as the “StB,” though there were many affiliated organizations). The report says this targeting began in the late 1950s and culminated with Arnold officially being taken into the security services in 1963, given the code name “ARNO.” His wife, Jitka (whom I met on a couple of occasions in 1987 and ’88), had already become an agent a few years earlier.

I can imagine the early- to mid-1960s were a golden age for Arnold. This was a period when his German-language skills and knowledge of trade unions were in especially high demand. Relations between Czechoslovakia and West Germany, at the time, were highly fraught and there were no formal diplomatic ties between the two countries. Indeed, whatever dialogue went on was often conducted through the trade-union network. The report credits Arnold with helping to develop these ties. Arnold, himself, said in testimony in 1990 that he had cultivated contacts at the time with many prominent German leaders, including Willy Brandt, Walter Ulbricht, and Erich Honecker.

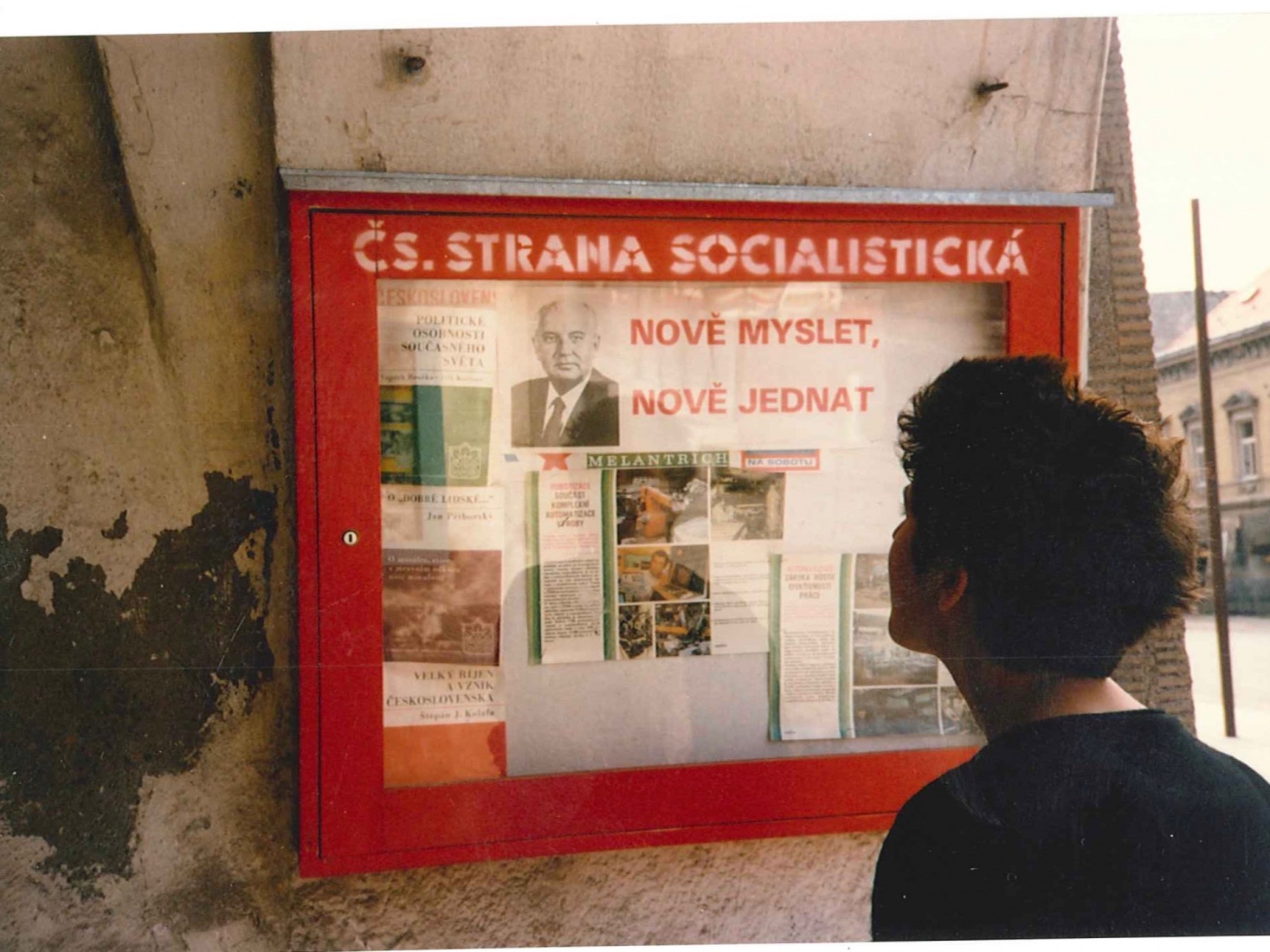

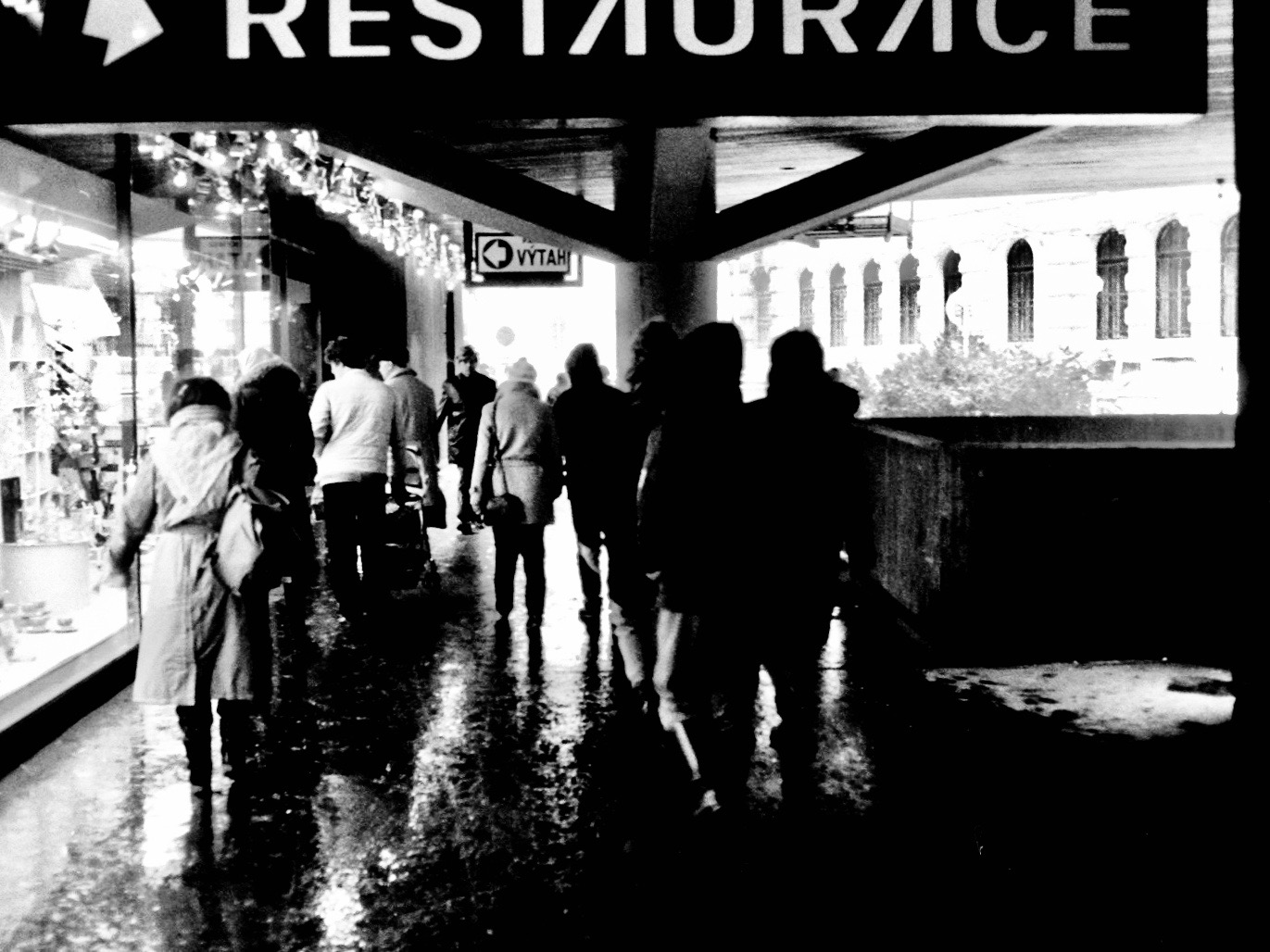

It all came to an end for him, and many of his contemporaries, in 1968 with the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion in August that year. The invasion stopped in its tracks the “Prague Spring,” Czechoslovakia’s democratic-reform movement of the mid-1960s. For reasons the report doesn’t go into or speculate on, Arnold sided with the reformers in that struggle, and when the Soviet military triumphed, he and tens of thousands of loyal Communists were expelled from the party and lost their jobs. Arnold was booted from both the Communist Party and the State Security Services, and eventually found low-level employment in the state-run “Restaurace a jídelny” (RaJ) company – the national catering service.

Here, the language of the report is particularly chilling:

“According to the StB, [Arnold] ‘had betrayed his political beliefs and joined the right-wing opportunists.’ … In July 1970, he was deprived of his membership in the Communist Party. At that time, this meant a profound decline in his material and social standing, and the end of travel to the West.”

Arnold stood with the pro-democracy reformers of his day and paid a high political price for it. At Business International, I was told that many of our in-country stringers, such as Arnold, had been “disgraced” Communists who had been unfairly punished for supporting the human values that we all shared. In Arnold’s case, at least, this was apparently true.

The part of Arnold’s story I was never told back then, though, was that by the late-1970s and into the 1980s (when I got to know him), he had staged an amazing political comeback.

Rehabilitation for Arnold was a gradual affair. The report says that by the mid-1970s, Arnold had renewed some informal contacts with the regional Prague office of the StB and begun a new career as a stringer for foreign-news outlets, starting with the German television station ARD, and then in the early ‘80s, ZDF. Detailed information from this period, though, is spotty owing to a lack of surviving documentation. Ironically, one of the few sources from this period is Arnold’s own public testimony, given in 1990. It should be noted in Arnold’s defense that, in that testimony, he denied he'd ever been a secret collaborator with the StB. Instead, he said, he’d been constantly harassed by the StB and was always too afraid to reject the agency’s overtures.

The next several pages of the report document the period through the 1980s to the run-up of the 1989 Velvet Revolution that overthrew Communism and the time immediately after, when the Communist-era StB was slowly dismantled. There’s too much detail to go into here, but the report paints a picture of a somewhat fractious relationship between the StB and a highly valued but occasionally obstinate agent. Throughout these pages, Arnold’s motives here no longer appear to be driven by ideology, but rather by wanting to build up a retirement nest-egg so that he and his wife could ride out their golden years in their suburban Prague home.

Knowing what I know now and looking back on that time in the late-1980s, when the long-term existence of the Communist regime could no longer be taken fully for granted, I can imagine it must have struck Arnold as supremely ironic that he might once again wind up on the wrong side of history. I imagine he was much more cautious about hiding his tracks and playing both sides of the conflict (and amassing as much cash as he could, while he could).

There’s one fascinating story from this part of the report that I’ll go into here in more detail. It’s particularly interesting to me for two reasons: One, is that the action takes place in Prague’s 6th district (Bubenec), not far from where I live. The second reason is that it’s a classic spy-vs.-spy story that deserves a little air-time in English.

The “Stanislav Pořický” affair of 1982 is spy-novel stuff. Pořický at the time was a washed-up former police officer working a low-level job at a campground in the Prague suburb of Branik. He was looking to make some money by selling some old intelligence, including possibly some nuclear information, to the U.S. or West German embassies. When Pořický met Arnold, who was visiting the campground with a ZDF television crew, Pořický thought his prayers had been answered. Who better but Arnold to negotiate a lucrative deal with a foreign embassy?

The details get complicated, but the story eventually leads to an elaborate StB sting operation that unfolds, allegedly, with Arnold’s direct assistance. Arnold helped to arrange a “chance” meet-up between Pořický and a purported American diplomat (whose part was played by another StB agent). To make the sting look more authentic, the “diplomat’s” car was fitted out with real U.S. diplomatic plates and the instructions to Pořický were even typed out on a typewriter stolen earlier from the American embassy by StB agents.

According to the instructions, Pořický and his girlfriend, Pavla Bednaričová, were to pick up some papers at a secret diplomatic drop box at the corner of Juárezova and Maďarská streets in Prague 6 (near my house, see map plot below). While at the drop box, they were filmed by the StB (I've posted some photos here). The couple was arrested a short time later. Both were eventually convicted of espionage – though neither had ever made contact with an actual foreign agent.

Pořický ended up serving seven years for the crime (he was released in 1990). Bednaričová was sentenced to five years, and served out the entire period. Arnold was mortified and angered by the affair -- humiliated that his role was essentially that of a stool pigeon.

Such was the stuff of Arnold that I never knew, and probably couldn’t have imagined in the late '80s, as we were driving around Prague from meeting to meeting in his Škoda or tipping back some wine with the directors of a cooperative farm.

In October 2017, I sat down over coffee with Dr. Tomek, the author of the report, to get some perspective from him on Arnold. I was also curious to know how much of Arnold’s file had survived and to ask if he had a photo of Arnold that I could use for my blog.

According to Tomek, Arnold was what he called an “extraordinary person.” Extraordinary in the fact that he had managed to maintain a relatively low, every-man profile but had still been highly influential in key moments. Tomek told me that the scope of Arnold's influence could be seen, ironically, in how much of his old file had been destroyed and how little of it had survived. “Clearly, he had some protection at high levels.” It seems that for old StB agents, having a small internet presence is a source of pride.

Tomek told me, additionally, that all of Arnold’s files from the period of 1987-90, in fact, spanning nearly the entire length of my own cooperation with him, had been destroyed. Apparently, my name and the name of Business International do not appear anywhere in the files (which is totally fine with me). Arnold left behind no surviving official photos.

What’s missing ultimately in all of this is Arnold’s motivation, and even Tomek is at a loss here to explain. “It’s clear that at one point, Arnold was a committed Communist,” Tomek said. But, like so many others, in the aftermath of the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968, he was broken and profoundly disappointed. Tomek said that in the 1970s and ‘80s, Arnold’s motives had probably shifted to some combination of making money and exacting a small measure of revenge on the regime. “But, of course, we’ll never know for sure.”

(This concludes a three-part series on Arnold and 1980s' Prague. Follow the links here to Part 1 and Part 2. Arnold makes a cameo in my post on Prague's Intercontinental Hotel. Next week, it's back to lighter fare and travel stories. MB)

Hi Mark,

thanks for sharing this interesting story!

Kind regards from Vienna

Marco

Hi Marco, Happy you liked it!

I love this story and really regret that I can’t have a beer with Arno….

I would have a lot of questions for him myself. Mark

Arno has or had a son,wife,partner and so the search goes on…..if you wish to know more about him.

Fascinating reporting about Arno, Mark. I was based in Vienna for Knight Ridder from 1980 until 1983. Or no worked as my fixer and translator on a wide range of stories in Prague. My wife and I also got to know Jitka. We always wondered what more there was to their story, of course. Thank you for filling in so many blanks!