Berlin was the most famous but by no means the only city in Europe to be divided by the Cold War. The cartographers of the Iron Curtain were unforgiving in the aftermath of World War II when it came to separating residents from each other in towns all along the perimeter where the communist “East” touched the capitalist “West.”

One of those places was České Velenice, and its sister city of Gmünd, in Lower Austria, which I knew from my train journeys up to Prague from Vienna in the 1980s as a reporter for Business International. Back then, the main Vienna-Prague rail line ran northwest out of Vienna and passed through southern Bohemia on its way up to Prague. (These days, the route starts to the northeast of Vienna and runs through Brno, east of Prague). This new route is longer, but quicker.

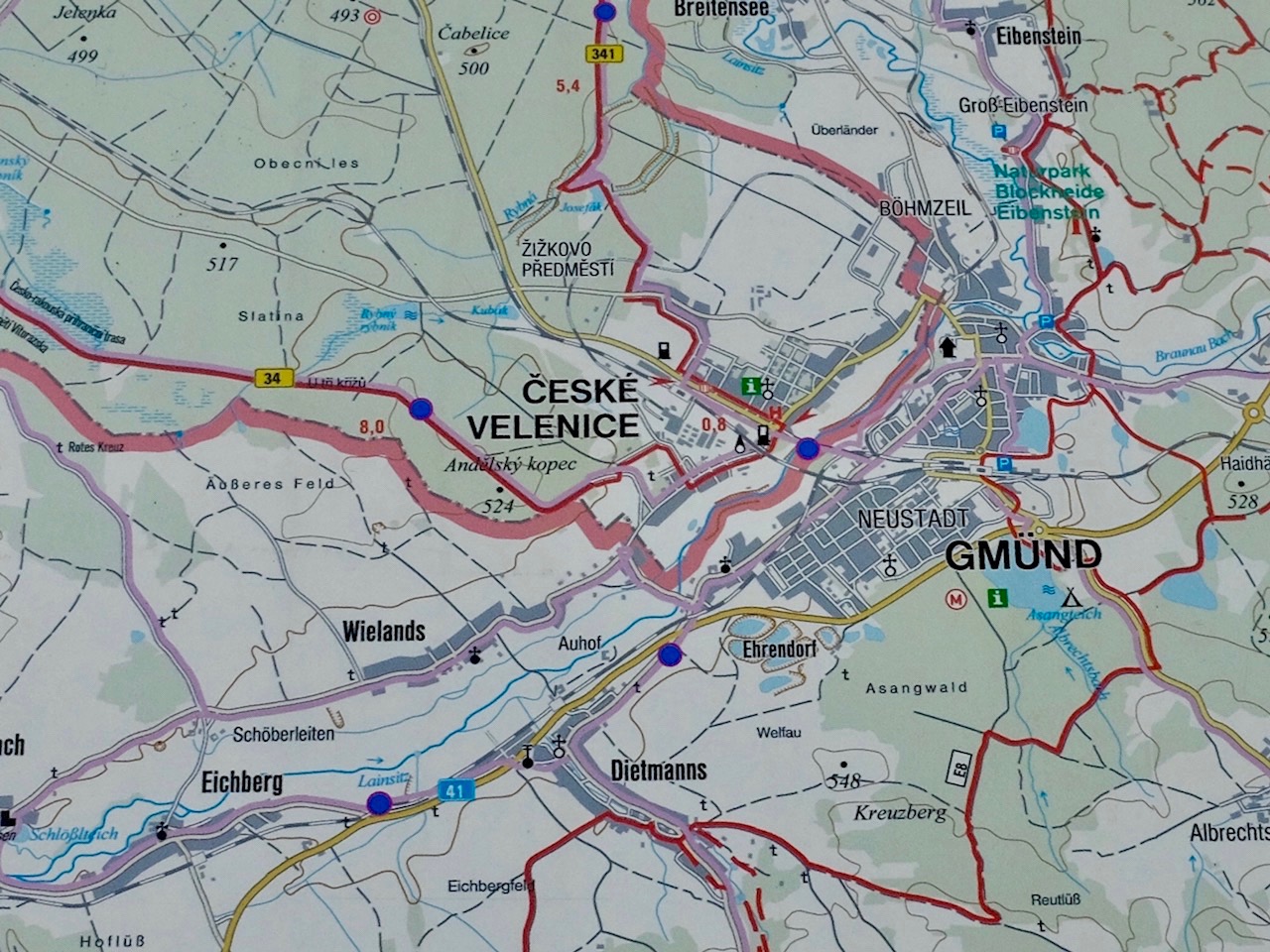

In the 1980s, when taking the train from Vienna to Prague, Gmünd would be the last stop in the "West" and České Velenice the first stop in "East." The irony, of course, was that historically they were the same place. The two train stations were separated by machine guns and barbed wire but were just 3kms (2 miles) apart.

Until Czechoslovakia's independence in 1918, the whole area was known simply as Gmünd, a town that traces its roots back to the 13th century and has the Gothic and Renaissance architecture to prove it. The name “České Velenice” was adopted after Czechoslovak independence in 1918 to describe that part of Gmünd that fell to Czechoslovakia. Until WWII, the region functioned essentially as one city (albeit with different languages and cultures).

It was only after the war and the 1948 Communist coup that the border became real.

I can still remember those work train journeys from the '80s like they were yesterday. The first leg, the two-hour trip from Vienna to Gmünd, would feel like any other Austrian commute. The train would be filled with school kids or businessmen or families visiting relatives in the provinces. Once we pulled into Gmünd’s small station, though, the carriages would empty out, the train would shut down, and most of the time I’d be left sitting alone for the short shuttle across the Iron Curtain.

We’d sit for a while, maybe a half hour or so, and the train would lurch back to life. We’d rattle on for a few minutes and chug our way into the Eastern bloc and České Velenice’s more-substantial station. The engineer would cut the motor again (but this time it felt real), the train would gasp, and then die. There was no telling when we’d continue onward.

Although I never left the train here during those early trips, fragments of České Velenice’s train station still haunt my dreams. In my mind’s eye, I see a nearly empty station, with a few workers washing the building’s windows or sweeping platforms devoid of passengers. The silence is palpable, pierced only by police whistles in the distance, a few muffled words between soldiers, and the inevitable banging up the stairs as the soldiers and customs agents board the carriages. At this point I know it’s only a few minutes until my compartment door slides open and I present my American passport and Czechoslovak entry visa to a startled agent.

The customs formalities on those trips were usually routine, and I never encountered any serious problems. Once – though not on one of these trips – I had agreed to do a favor for some Polish friends by carrying several thick rolls of old Polish złoty on a train across the Czechoslovak border into Poland. Importing currency back then was strictly verboten, but I was seldom checked and happy to help out a young couple who needed the money to buy a house. I’d completely forgotten about those wads of cash (which was hidden in some socks in my suitcase) until the border agent on the train pointed to my bag on a rack above my head and asked to look inside. I broke into a cold sweat and could scarcely lift the suitcase without shaking. He made a quick search, found nothing and wished me a pleasant journey.

Though I had passed through Gmünd-České Velenice half a dozen times from 1987 to 1989, I never had any reason to get off the train and had no idea what the town was really like. So what did I find when I finally had a chance to take the place in?

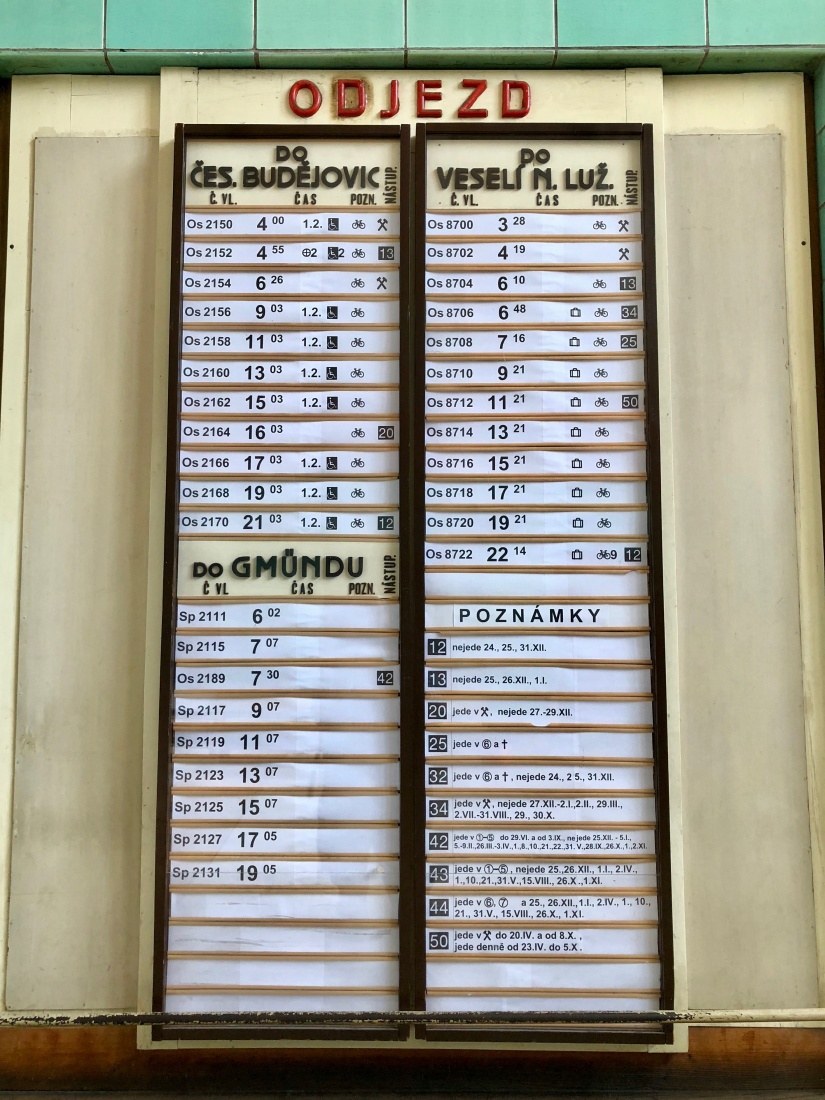

The first thing I noticed was how quiet České Velenice’s empty, oversized train station really was. A quick scan at the timetable revealed that not many trains pass through here these days. After the Vienna-Prague line was re-routed in the '90s, the station was downgraded -- and still coping with the relegation.

This must have been quite a climb-down. This station was one of the original stops on the historic Franz-Josefs-Bahn (the Emperor Franz Joseph Railway), the first direct rail line between Vienna and Prague in the mid-19th century. České Velenice owed its impressive station to its position along this once-important link.

The other thing I noticed is that Gmünd and České Velenice still feel very much like separate places -- even though the Iron Curtain was pulled down 30 years ago and the pre-World War II “border-less” status between the two has been restored. Indeed, the hideous Cold War-era checkpoint along the main road linking the two centers is still standing. It's unguarded and unmanned, but the checkpoint's very presence remains a stark reminder of recent history and may even reflect lingering skepticism on the part of residents that open borders are really here to stay.

Or maybe residents are simply uncomfortable on some level with the fact that České Velenice and Gmünd are now, once again, essentially one place? It’s hard to say. It may take many more decades before residents of both parts of town fully re-embrace their shared geographic and historic identity.

Modern-day Gmünd, which incorporates the town’s historic center, appears to be the far more prosperous part of town. On my visit on a hot Saturday afternoon in August, the restaurants and ice-cream parlors along the main square were doing a booming trade.

Central České Velenice, by contrast, just a couple of kilometers away, was nearly empty. To be fair, this was always an underdeveloped part of Gmünd, even back in the day. Judging by the signs out front, most of the shops here cater to various border-town vices like gambling, prostitution and garden gnomes. Most prices are denominated in euros (not Czech crowns) and the parking lots are sprinkled with Austrian plates. It’s pretty clear who’s doing the selling and who’s doing the buying.

I’ve never actually seen a town filled with so many grandiose brothels, but even these appear to be falling on hard times (scroll down beyond the map for more photos).

Truth be told I was a little let down by the visit. I’m not sure what I was expecting. I suppose I was hoping that something of the European Union good-neighbor ideal might have made more of an impression by now, and that commerce and living standards would be more balanced.

The high point of my trip came when I got on my bicycle and rode through some of the fields surrounding the town that mark where the old Cold War frontier once stood. The EU’s “Iron Curtain Cycling Trail” follows an old narrow-gauge railway that once linked the big train station in České Velenice with the historic center of Gmünd. It's only once you're out on the bike that you realize just how close these places really are to each other.

It’s a beautiful ride through unspoiled, open fields, and as I was cycling I came up with an instant note-to-self, bucket-list aspiration: to follow this trail someday end-to-end. It would be a spectacular ride.

(I wrote about the funny things that could happen on the train ride up to Prague from Vienna in an earlier post: Part 2: My Czech Friend 'Arno')

Very interesting! Thanks for writing and posting this artie. There are two reasons why I want to visit ?eské Velenice: 1/ It is one of the few Czech places which do not belong historically to Bohemia/Moravia/Silesia. 2/ A railway employee managed to preserve Masaryk’s train carriage here (if i remember correctly). It is in a different location, pity, as it could slightly offset the predominant local lines of business.

Thank you, Tomas! I would love to see Masaryk’s train carriage and will look for it on my next visit. Mark

Intriguing story indeed. I am also puzzled by your remark about garden gnomes and border towns. Is it for everywhere or just in Czech Republic?

I am not sure but the two seem to go together for some reason.

Very interesting story as always on this blog.

What is the story behind all the Czech border towns with a sizable Vietnamese community?

I’m not really sure, but there are many Vietnamese people in the Czech Republic going back to communist times. For some reason, members of this community have repopulated formerly depressed areas and cities along the border areas. Maybe it’s because they saw economic opportunities to try to revitalize these areas or the cost of living was simply lower.