One of the biggest changes ushered in by the anti-communist revolutions across Central and Eastern Europe in 1989 was that local populations, trapped for decades behind the old Iron Curtain, could now finally, freely travel abroad. No longer was it necessary to apply in advance for special exit visas simply to cross the border. No longer was permission to travel contingent on subjective factors, such as one’s loyalty to the regime or whether one constituted a heightened asylum risk. Like in any other free country, foreign travel – thankfully -- could now be taken for granted.

The flip side of that coin, though, was also important. Not only could people within the region go wherever they wanted, but the changes also opened up the former Eastern bloc itself to travelers from abroad – and to the ideas, energy and money these visitors brought with them. To be sure, tourists from the non-communist world could always visit countries like Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland, but it wasn’t common or easy. Travel to the Eastern bloc often required a lot of advance planning, starting with the costly, time-consuming process of obtaining an entry visa. Then there were the added hassles of mandatory currency exchanges and requirements to pre-book tours and hotel rooms.

I know all this firsthand because I was frequent traveler myself to the communist Eastern bloc in the 1980s as a journalist living and working in Vienna. Whenever I traveled from Vienna to Czechoslovakia back then, the Czechoslovak consulate always made the process of getting an entry visa as frustrating for me as they possibly could. The embassy was only open on certain days of the week and, on those days, only a few hours. The lines moved painfully slowly. At closing time, the visa window would slam shut. If I hadn’t made it to the front of the line by then, I’d have to come back the next day. Those entry procedures, of course, paled in comparison to the difficulties the populations behind the Iron Curtain themselves had to contend with if they wanted to leave their countries. Nevertheless, the hassles proved enough of a barrier to keep the number of foreign – particularly Western – visitors to the region relatively low.

The stigma surrounding the Cold War itself also acted to suppress tourism. European travel maps from the 1970s and ‘80s often clearly delineated the countries on the western side of the continent, like France and West Germany, but rendered the lands to the east as splotches of blank space (as if these places didn’t exist). Popular notions of “Europe” before 1989 automatically conjured up images of the Eiffel Tower, the Colosseum, or “Big Ben.” Ask someone, though, to identify a comparable landmark in an Eastern-bloc city like Prague, such as Charles Bridge, and you’d get a blank stare. Even if travelers had been familiar with Eastern Europe, they would have been scared off by stories of Soviet military interventions in the region, such as Budapest in 1956, Prague in 1968, or in Poland under martial law in the early ‘80s. Names like “Prague” or “Budapest” – to the extent they were uttered at all – assumed an exotic cast, like something from the pages of a John le Carré spy novel. The 1989 revolutions, particularly Czechoslovakia’s dramatic Velvet Revolution, put the Eastern bloc back on the travel map – and they were now easier to visit than ever.

In late-1990, my girlfriend, Delia, received a surprise job offer from the American travel publisher, Fodor’s. The company planned to launch an ambitious new English-language guide on Czechoslovakia to take advantage of this new-found ease in traveling to the formerly communist Europe and wanted to know if she was available to write it. She was thrilled to get the commission and quickly accepted. She then asked if I would take leave from my job and travel with her through the country for a month as her co-author. We would be writing one of the first English-language guidebooks on Czechoslovakia to appear in a generation. We were both excited by the chance to introduce the country to foreign travelers. The only problem was neither of us knew all that much about the place ourselves.

Introducing Delia

Before I begin with the journey itself, allow me briefly to introduce my travel partner and reason for this trip. Throughout the years I lived in Vienna, from 1986 to 1991, Delia was both my girlfriend and closest friend. We first met in 1985 at New York’s Columbia University, where Delia was a visiting student from Britain. She was pursuing an MA in politics while I studied at the School of International Affairs. We were dating in the spring of 1986, when I received a job offer from a small publishing company, Business International, to work as a reporter in Vienna. Delia shared my interest in Central and Eastern Europe, but she was reluctant to leave New York. Sometime later, though, she came up with a plan to focus her master’s thesis on Austrian politics, which allowed her to relocate full-time to Vienna. We stayed together – with a few hiccups in between – until the middle of 1991.

Delia’s own family connections to Central Europe went much deeper than my own. I had known Delia’s father, Otto, mainly as a successful research chemist back in the UK, but I came to learn later, as Delia and I pondered our trip, that he had started out life under very different circumstances. Otto was born in Holland in 1935 as the son of a German-Jewish mother and a German father who’d been a Nazi sympathizer and member of Hitler’s Sturmabteilung, the SA. Delia’s father was one of 10,000 predominantly Jewish children – part of the “Kindertransport” rescue effort – who were relocated out of Germany and German-occupied territories to the UK in the months after “Kristallnacht” in November 1938. Otto had traveled in transport number 7048.

After the young Otto had left for the UK, his mother (Delia’s grandmother), Dorothea, stayed behind in the southern German city of Ulm, where she worked as a caregiver to elderly Jewish patients. Dorothea managed to remain in Ulm until mid-1942, when the Nazis deported her to the Jewish concentration camp at Terezín (Theresienstadt), north of Prague. She, along with many thousands of others, was later transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered. In early 1991, as Delia and I planned our route, we circled Terezín as one of our main stopovers. For me, the visit would be a chance to learn more about a dark chapter of European history; for Delia, the emotional stakes would be higher. She would be retracing the steps of her late grandmother.

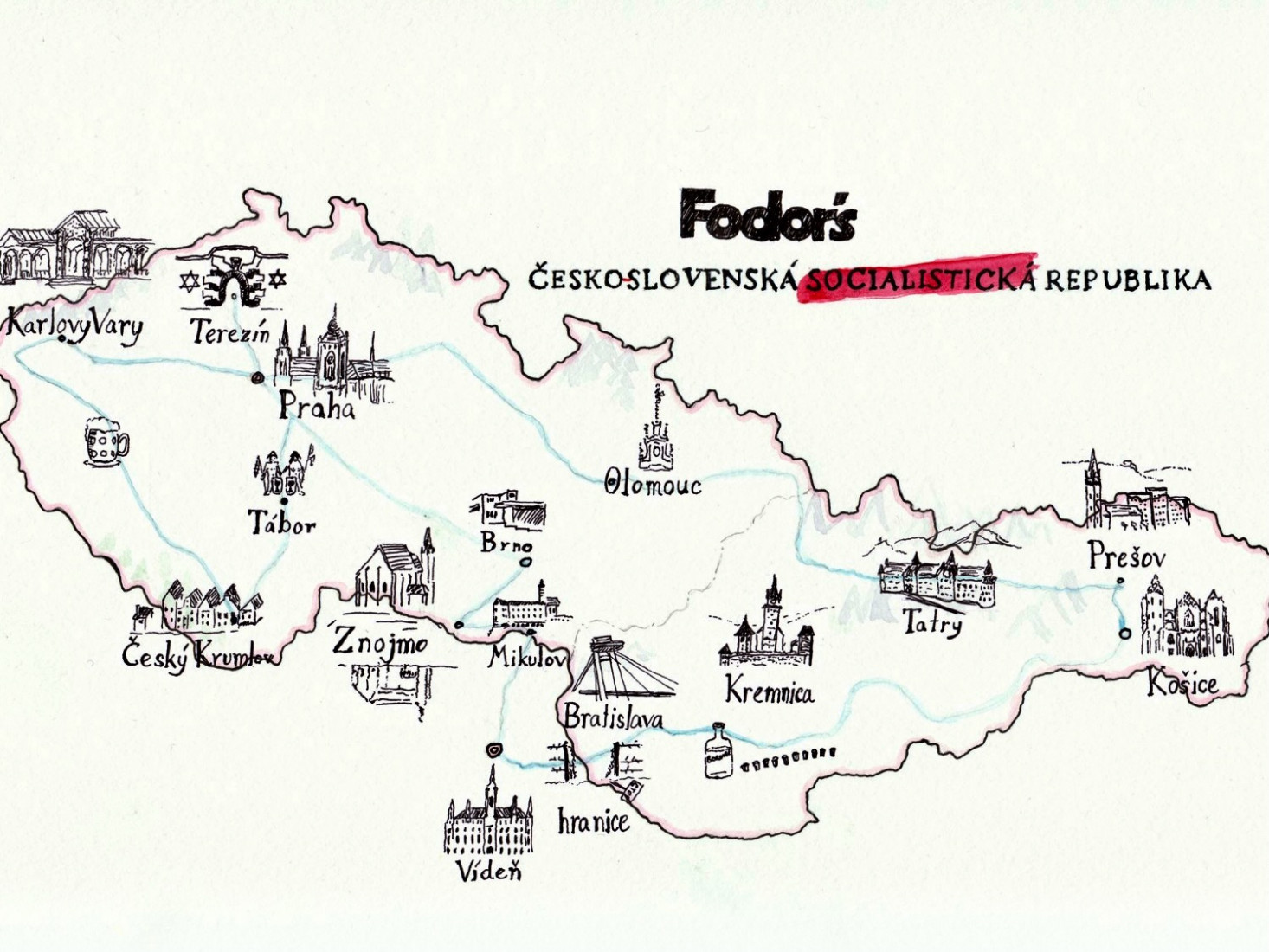

On the morning of February 1, 1991, the first day of what would be the region’s coldest February in many years, Delia and I packed up our rental car, drove north beyond the city limits of Vienna, and began a month-long circuit around Czechoslovakia. Because we were writing a completely new guidebook – and not working from an existing guide – we were free to choose our own itinerary, including which cities and towns to highlight in the guide and which ones to leave out. These days, both Czechia and Slovakia are popular destinations and have long, familiar lists of tourist attractions. Back in 1991, the situation was very different. There was no such thing as a well-trod tourist trail. We penciled in a handful of places that were obvious “must-sees:” Prague, Bratislava, the famous spa resorts of Western Bohemia, the High Tatras, and, of course, Terezín. But we still had 200 blank pages to fill and little idea of what other sights Czechoslovakia had to offer.

Why Us?

With our relatively limited knowledge of the country’s tourist offerings, Delia and I admittedly were not perhaps the ideal team to write a definitive guidebook on Czechoslovakia, a book that travelers from around the world would rely on for their first look at the country in decades. I had reported on Czechoslovakia’s political and economic structures at Business International but still had lots to learn about its history and culture.

As I page through the book now, I see that we did indeed “discover” some new places, like Český Krumlov, that were undeniably beautiful but still relatively unknown outside Czechoslovakia. We also, though, included several places that, in retrospect, never caught on with tourists. For example, we spent several days traveling through the remote but otherwise not very noteworthy western border towns of Klatovy and Domažlice. We also fell in love with the little town of Písek, south of Prague, with its miniaturized version of Charles Bridge, but the international crowds never followed.

In our defense, though, I’ve found – after years of working now as a travel writer – that comprehensive knowledge of a destination is only part of the formula for writing a good guide. An equally important component is knowing the reader. It’s essential for travel writers to be able to describe places in ways that readers can process and make sense of through their own knowledge and experience. When writing on Czechoslovakia, for example, it makes little sense to tell long, involved stories about local history, about Emperor Charles IV, or Jan Hus, or Tomáš Masaryk, or even Václav Havel, without also tying those individuals and events to the lives of readers. Without this link, the stories cease to have any meaning.

Setting Readers' Expectations

With respect to knowing the reader, at least, the two of us were better-suited to the task. Many Fodor’s readers would be people exactly like us: travelers who’d been inspired by the collapse of communism and who were eager to explore the newly liberated country. We also had an instinctive feel for what our readers’ expectations might be in advance of their trips. We knew that travelers would be shocked and disappointed – perhaps unfairly – to see the widespread neglect left behind by four decades of communist rule. We knew that many of the attractions in our book, including the castles, museums, town squares and public parks, had fallen into appalling states of disrepair. Those old, communist-era hotels, restaurants, roads and trains weren’t up to international standards either.

We used the book’s introduction to encourage readers, instead, to modify their expectations, to look beyond the drab remnants of socialist reality and see the country’s underlying beauty. We tried to cast any disappointments that travelers might encounter as simply a part of the adventure itself: rediscovering a country in the process of rediscovering itself. This was how we presented Czechoslovakia to our readers in 1991:

“The peculiar melancholy of Central Europe, less tainted now by the oppressive political realities of the postwar era, still lurks in the narrow streets and forgotten corners. Crumbling façades, dilapidated palaces, and treacherous cobbled streets both shock and enchant the visitor used to a world where what remains of history has been spruced up for tourists … For those willing to put up with the inconveniences of shabby hotels and mediocre restaurants, the sense of rediscovering a neglected world is strong.”

So, that’s the backstory to our Fodor’s guide. In the next three posts, I’ll invite readers here to fasten their seat belts and travel back in time with us to a cold February in 1991 and marvel at how far the country (now two countries) has come. There’s not enough space here to include every stop along our journey. Instead, I’ll focus on a handful of places and recount our impressions. Click here to continue reading Part 2.

*Rough Guides also published a travel guide on Czechoslovakia around the same time.

Did you like the story and want to add your own experiences? Or maybe help me to correct something I didn’t get right? Write me at bakermark@fastmail.fm.