Though it may not look it at first glance, Wenceslas Square is more than a string of strip clubs and currency booths – at least it is to me. My job as a journalist first brought me to the Czech Republic some 30 years ago, and the square has always left me with a feeling of strangeness and mystery. As I researched the article, I tried to tap into that odd energy I’d always felt here and to peel away a bit at the square’s façades.

My aim was to dig deeper into the history, architecture, culture and psychology of a space that has stood at the heart of Prague for six centuries (it began life as a horse market in the 14th century). I wanted to take the pulse of the place, both during the day and at night. I discovered quirks and features that tell stories not just from the past but also reveal some of the contradictions of modern life in the Czech Republic.

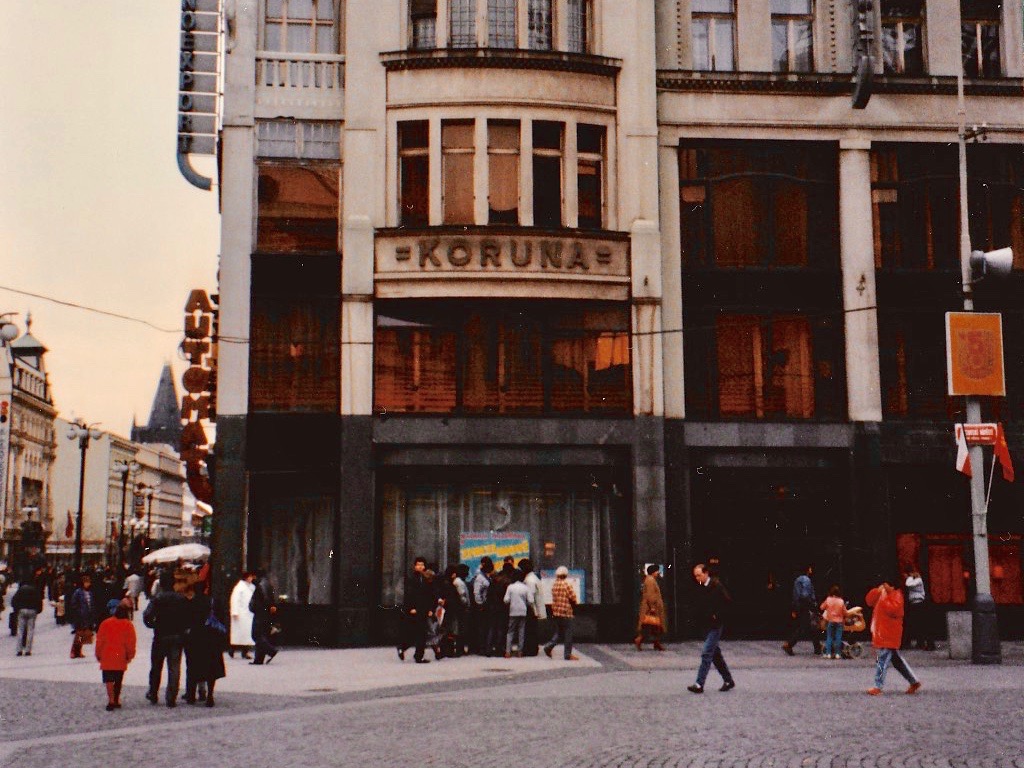

My own first memories of Wenceslas Square are hazy. It was some time in the 1980s – possibly in 1987. At the time, I was a naïve, twenty-something reporter for a publishing outfit affiliated with the “The Economist,” based in Vienna. I was visiting Prague on a business trip and I remember taking a meal at the "Automat Koruna," a popular cafeteria that once occupied the ground floor of today’s Palác Koruna on the lower end of the square.

During those times, it was mandatory for Western journalists to be accompanied by a local translator, and on this day I was accompanied by “Arnold,” a tired-looking Czech man in his late 50s whose job it was to help me navigate the city.

We had just finished our meals and Arnold had gone to the counter to get a coffee. I recall feeling restless, and I decided to leave the table for a moment to get some air and take a walk. My motives were as innocent as that. I hadn't gone further than a few meters when Arnold, out of nowhere, appeared in my face. He was angry with me – much angrier than he should have been under the circumstances. “You can’t just leave and take a walk without telling me,” he said, with a hard look in his eye. “Never do that again.”

Suddenly, everything became clear. Arnold wasn’t just my "translator;" he was also my minder. It was his job to watch me, assess me, and report back on what I did and what I said. Many years later, I found documents on the internet that indicated that Arnold -- or "ARNO" (his code name) -- indeed worked for the Czechoslovak State Security Service (StB). (Read more about Arnold's true identity here.) Even today, three decades later, something of that odd and spooky encounter lingers as I walk along the square’s wide sidewalks.

Václavák By Day

For the “day” part of my exploration, I was accompanied by Petr Kučera, a Prague-based urbanist and architectural historian involved in preservation projects around the city. It’s fitting, perhaps, that one of our first stops is a return to the Palác Koruna, one of the square’s iconic buildings, from 1914, and one that still recalls something of its early-20th-century splendor.

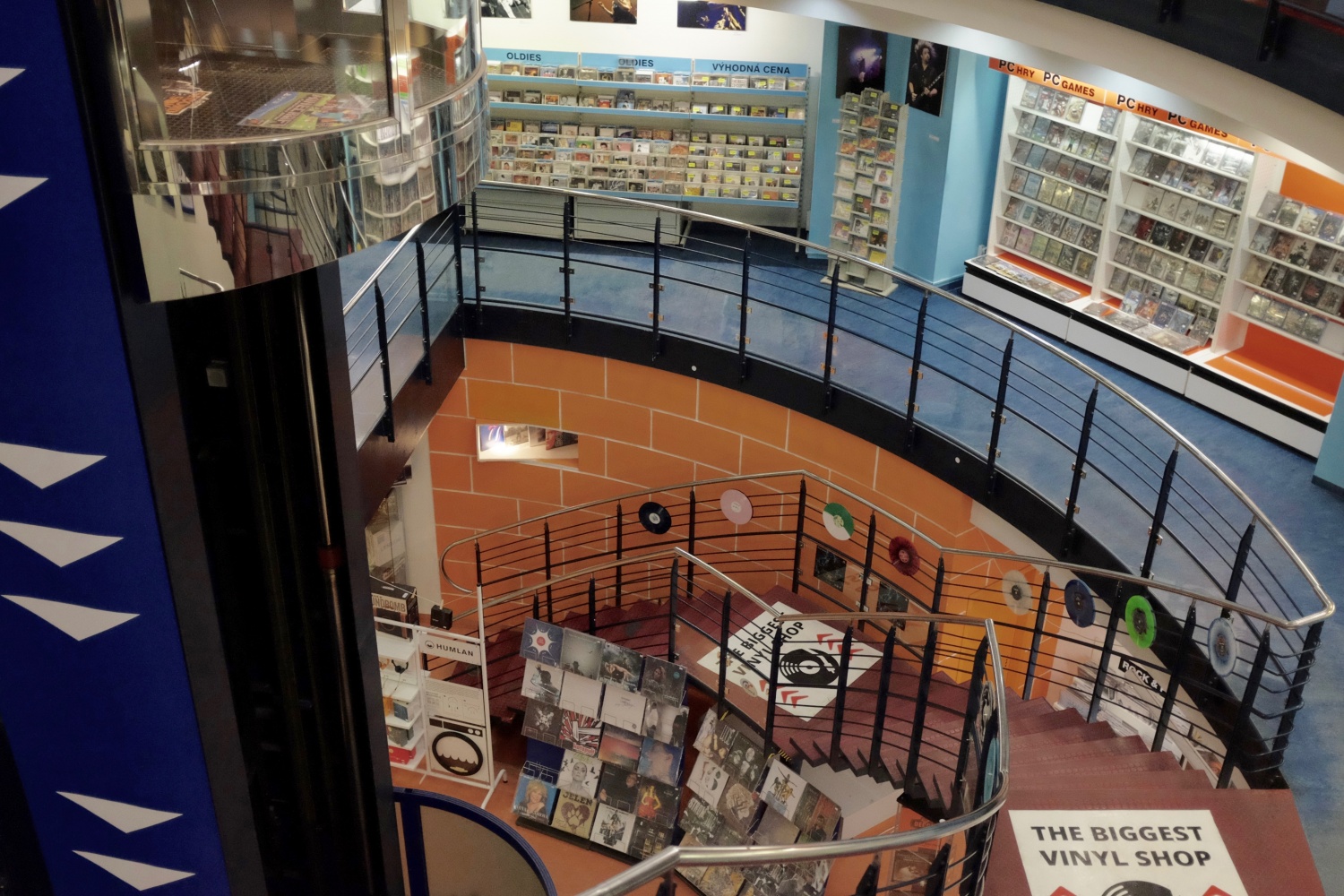

“It’s a classic example of a 'poly-functional' house,” Kučera says. “It embraced an American idea, popular at the time, of the vertical city.” The concept was that a building should house all of the functions needed for daily life. One of the building's grandest features, he points out, was a ground floor made of glass, now covered in tile, which once looked down on a luxurious octagonal swimming pool. The shape is still reflected in the lobby’s glorious stained-glass ceiling.

To see the former pool, simply walk downstairs through the former Bontonland music shop, find the spot that approximates where the stained-glass ceiling is, and look down. The layout of the store, with its various layers and depths, looks exactly like the shape of a swimming pool.

Once back outside, Petr and I stand at the bottom of the square and take in the sweep of buildings and their various styles, ranging from the neo-Baroque and neo-Renaissance that was so popular in the 19th century to the more-daring Secession, Art Nouveau, and Functionalism of the last century. Kučera points to an early-Art Nouveau building at no. 12, dating from the turn of the 20th century, as one of his personal favorites. It was groundbreaking, he says, because it was pure Art Nouveau without any historical influences. “Architectural conservatives hated it,” he says.

If there was ever a “golden age” on Wenceslas Square, it would have been in the 1920s and ‘30s, when the square was home to 13 cinemas, as well as dozens of cafes, publishing houses and even private apartments. These days, in a city of over a million people, barely 100 people actually live in the buildings on the square. Wenceslas Square was covered in so much neon lighting at the time, it was called “Trafouš” or “Trafo” in local slang, a reference to London’s bustling Trafalgar Square.

Wenceslas Square was not just a social hub, but also a place of important architectural experimentation. Daring Functionalist buildings, such as the Hotel Juliš at no. 22 and Palác U Stýblů at no. 28, attracted international attention. Kučera says the French architect Le Corbusier was a fan of Trafouš, particularly the cafes that once ringed the square one floor above street level. “Corbusier said if you built a series of door that connected all of the buildings, you would create one long café,” Kučera says.

Sadly, little of this upper-floor café culture has survived to the modern day, though ironically the second level of Starbucks at no. 40 on the square has retained its original ceilings. Perhaps the best-preserved interior that reflects the decadence of the time is below ground at the Triton restaurant (no. 26). The grotto-like cellar, with its stalagmites and hidden references to Greek and Roman mythology, remains undisturbed, but more-ghoulish touches, like tables made to resemble coffins and glasses fashioned to look like skeletons, are now mere memories.

The once-grand Palác U Stýblů (home to today's "Alfa" passage) is nearly vacant and is perhaps the best example of modern-day dysfunction on the square. Kučera says, though, the ground-floor passageway actually hides a secret of its own. Anyone who believes that sex and prostitution are modern features of Wenceslas Square might be surprised to learn that decades ago there was once a “sex cabin” standing in the building’s lobby, where men could pay their money, go inside, and have their fun.

Modern development schemes, including a four-lane highway added in the 1970s at Wenceslas Square's upper end (that separates the square from the dominant National Museum), have not been kind to the space. Kučera adds that further damage was done in 1983, when the square was last fully renovated. “The communist authorities wanted to create the illusion of a public place, but not actually give people any space in which to gather.” That meant dividing the surface of the square into smaller, discreet sections and filling the sections with plants and gardens. All of that backfired, of course, in November 1989, when hundreds of thousands of protesters simply trampled over the plants to demand a return to democracy.

Václavák After Dark

By night my guide to the square is “Karim,” a former male prostitute in his early-40s, who spent more than a decade working the streets on and around the square. These days, through a group called Pragulic, he earns money by leading tours to show people the harsh realities of street life after 10pm, long after the office workers have gone home and the sidewalks fill with shady touts in big hats luring visitors to a night of expensive drinks and a striptease or two.

Karim is a likable, lucid man with a tough backstory and an appearance to match. On the evening of our tour, he’s wearing layers of what appear to be second-hand clothing, plus multiple rings, chains, and tattoos. It’s dark outside when we first meet in front of Prague’s main train station (not far from the square). Nevertheless, Karim is wearing sunglasses, which he quickly lifts to reveal eyes caked in mascara. It’s a shocking first impression.

As we walk south from the station toward the top of the square, near to where the National Museum now stands, Karim is eager to talk about the life of the homeless, the drugs, the money-laundering, the prostitutes, and the gangs. It’s hard for me to know exactly where hard-earned fact blends into Karim's elaborate fantasy (he certainly has the street cred to know what he’s talking about). Even if half of what he says is accurate, it paints a pretty bleak picture.

Karim says Prague has around 9,000 homeless people and many of them spend their days and nights on or near Wenceslas Square, sleeping in trash containers (dubbed “Interconti” in slang, an ironic reference to the upscale Intercontinental Hotel), or in the passages, tunnels, and parks around the train station and top of the square.

In Karim’s world, those pretty Art Nouveau and Functionalist buildings, so dear to the hearts of architects like Petr Kučera, are little more than decorations that line an asphalt turf fought over by a half-dozen or more criminal gangs, including Russians, Black Africans. Bulgarians, and Albanians, who operate under the watchful gaze of an ineffective (and possibly complicit) police force.

The square’s dividing line, Karim says, is the axis running roughly north-south, defined by Jindřišská and Vodičkova streets. This line bisects the square neatly into a wilder, more-lawless upper part and a calmer, more-orderly lower section.

That’s not to say, of course, there aren’t many perfectly legitimate businesses and clubs that operate on the square, or that the ills Karim describes are actually new problems. After all, gambling, prostitution and even drugs have been part of life on Wenceslas Square for many decades, if not longer.

City officials have ambitious plans to clean up the square, but it’s unclear whether or not they will succeed. The square’s biggest problem, and one that can’t easily be fixed, might simply be its shape. At around 2400 feet (720 meters) long and 200 feet (60 meters) wide, a ratio of 12:1, it’s neither truly a square nor strictly a street. “A square is for sitting, a street is for moving,” Kučera points out.

This geometric tension creates a schizophrenic feeling among the passers-by of both stopping and starting – of not knowing whether to stay or to go – and that will always exist to some degree, no matter how much they try to clean up the place.

(Portions of this post first appeared in Mlada Fronta Dnes’s ‘City Life’ magazine. Since this article appeared, the city has announced plans to improve the square, including widening the sidewalks and adding more trees -- but possibly not, as was expected, restoring the tram line that once ran down the center of the square.)

For most of my 10 years living in Prague (99-09) I loved Václavské nám?stí more than pretty much all the other squares in the city (weird side note, places in Prague don’t exist for me in English, it’s almost like an alternate world that had little meaning to my life in the Czech Republic). Sure, there were hordes of tourists, though in the early Noughties it seemed as though the city was quiet from New Year until early February when the first Italian tourists of the year would turn, like migratory birds, but the square had a monochrome grittiness that contrasted with the colour and panache of Starom?stské nám?stí. For the last few years of that decade I lived right at the opposite end of Opletalova, next door to Masarykovo nádraží, and spent many hours on the square just watching the ebb and flow of people, the innocence of the tourists, the criminality of the gangs you mention. I can think of few urban spaces I have loved more.

I first came to Prague in 1999 for a long weekend and was staying 5 metro stops away from Wenceslas Square at Budejovicka. From the moment I set foot on the square from the Museum metro I had the strangest feeling that I knew this street. That I was home.

Now it is 2019 and I have not been in London, where I’m from, or England for 13 years.

For most of that time I have lived close to Wenceslas Square. For the past 6 years I have lived on a street directly off Wenceslas Square.

I have worked there. I have made friends for life there. I have partied there. I have M&S there, ha ha.

I love walking the Square at dawn, watching those going to work or finishing their night. So many funny memories.

I first saw Wencelas Square in November 2006, after exiting the Mustek Metro Station. It was night and my first impression was of a similarity to Canal St. in New Orleans, another very wide boulevard. It was only when I had walked through the lower square and suddenly and unexpectedly came into Old Town Square that I fell in love with Prague.